Otorhinolaryngology/maxillofacial disorders

Key Points

The upper respiratory tract (URT) includes the nose, paranasal sinus, pharynx and larynx but the salivary glands and oral cavity are closely adjacent. Otorhinolaryngology specialists (ear, nose and throat; ENT) deal mainly with the nose, paranasal sinus, pharynx and larynx, and often employ binocular microscopy (Fig. 14.1) and nasendoscopy. Salivary disorders are discussed mainly in this chapter, as well as Chapters 18 and 22, oral disorders in Chapters 11 and 22. The URT may become damaged by pollutants such as smoke, soot, dust and chemicals, or infected with microorganisms from the inspired air. Pain from sinus or aural problems may radiate or be referred to the mouth; equally, oral problems may cause pain in the sinus or ear.

Upper Respiratory Tract Infections (URTI)

A wide variety of respiratory pathogens may cause a single clinical syndrome and, vice versa, any one pathogen may cause a range of clinical diseases. Most URTI are viral.

The URT is also colonized by normal bacterial flora, which rarely cause disease, but may under certain circumstances cause upper or lower respiratory tract (LRT) or even systemic or transmissible infections. For example, the normal nasal bacterial flora may include Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis and aerobic corynebacteria (‘diphtheroids’). Some people carry meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in their nose, which can cause disease (Ch. 21). Bacterial infection caused by a foreign body introduced into the nose of a child (e.g. a small toy) is a well-recognized cause of halitosis, as are tonsillitis and sinusitis. The nasopharyngeal bacterial flora may include non-encapsulated or non-virulent strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae, which may cause meningitis. Pharyngitis can be caused by group A streptococci (and can rarely lead to rheumatic fever and occasionally rheumatic carditis; Ch. 5) or can be caused by Epstein–Barr virus (Ch. 21).

Viral Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Viruses frequently evade URT defences to produce infections; children have up to eight UTRIs per year, and adolescents up to four. Viral URTIs are highly infectious in the early stages and most are contracted by shaking the hands of infected persons or by touching things that they have touched (and then touching the nose, mouth or conjunctivae; Table 14.1); infection may also be spread via sneezes. The incubation periods rarely exceed 14 days. The incubation times of the common agents are:

Table 14.1

| Viral respiratory pathogens | Presumed viral respiratory disease |

| Adenoviruses | Coronaviruses |

| Influenza viruses | Coxsackie viruses |

| Para-influenza virus | Cytomegalovirus |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | ECHO viruses |

| Rhinoviruses | Epstein–Barr virus |

| Herpes simplex viruses | |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) |

The three main clinical patterns of URTI are the common cold syndrome (coryza), pharyngitis and tonsillitis, and laryngotracheitis.

Other URTIs are discussed in Chapter 21.

The common cold syndrome

General aspects

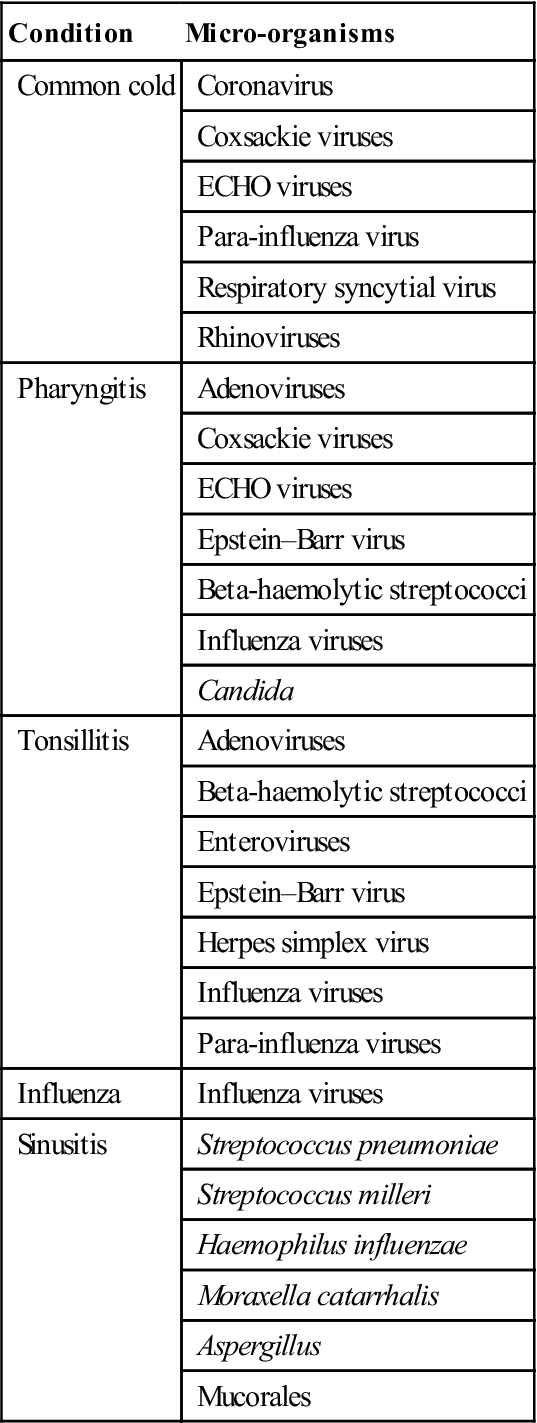

The common cold is caused not by a single organism but usually by rhinoviruses; it can, however, be caused by more than 200 different viruses (Table 14.2), particularly by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronaviruses, and para-influenza and influenza viruses).

Table 14.2

Upper respiratory tract infections and their main causes

< ?comst?>

| Condition | Micro-organisms |

| Common cold | Coronavirus |

| Coxsackie viruses | |

| ECHO viruses | |

| Para-influenza virus | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | |

| Rhinoviruses | |

| Pharyngitis | Adenoviruses |

| Coxsackie viruses | |

| ECHO viruses | |

| Epstein–Barr virus | |

| Beta-haemolytic streptococci | |

| Influenza viruses | |

| Candida | |

| Tonsillitis | Adenoviruses |

| Beta-haemolytic streptococci | |

| Enteroviruses | |

| Epstein–Barr virus | |

| Herpes simplex virus | |

| Influenza viruses | |

| Para-influenza viruses | |

| Influenza | Influenza viruses |

| Sinusitis | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Streptococcus milleri | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | |

| Aspergillus | |

| Mucorales |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Clinical features

Sneezing, mucus overproduction with nasal obstruction, nasopharyngeal soreness and mild systemic upset are common. Bacterial infection may supervene and cause sinusitis or middle ear infection (otitis media), but serious complications are rare in otherwise healthy patients.

General management

Only symptomatic treatment is available.

Dental aspects

Elective dental care is best deferred. General anaesthesia (GA) should be avoided since there is often some respiratory obstruction and infection can spread to the lungs. If a GA is unavoidable, it is best to intubate with a cuffed tube, so that nasal secretions do not enter the larynx. Antimicrobials may be indicated for prophylaxis. Xylitol chewing gum has been shown to reduce the risk of otitis media, presumably by inhibiting pneumococcal superinfection.

Pharyngitis and tonsillitis

General aspects

Most cases of pharyngitis and tonsillitis are caused by viruses (see Table 14.2), some by streptococci.

Clinical features

The throat is sore, with pain on swallowing (dysphagia) and sometimes fever and conjunctivitis. Enlargement of the tonsils with an infected exudate from the crypts, together with cervical lymphadenopathy, is characteristic of tonsillitis. Prominent submucosal aggregates of lymphoid tissue may be evident in those with pharyngitis. Complications are rare but may include peritonsillar abscess (quinsy), otitis media and, rarely, scarlet fever, acute glomerulonephritis or rheumatic fever.

General management

Infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever) or, rarely, diphtheria may need to be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Tonsillitis caused by bacterial infection is best treated with benzyl or phenoxymethyl penicillin, or, if the patient is allergic, by erythromycin or a cephalosporin. Ampicillin and amoxicillin should be avoided, as they tend to cause rashes, especially if the sore throat is misdiagnosed as a streptococcal sore throat but is due to glandular fever.

Pharyngitis is not often treated with antimicrobials, as there is no evidence that they accelerate resolution or reduce complications; an increasing body of opinion advises simple analgesics.

Dental aspects

Elective dental care is best deferred. GA should be avoided since there is often a degree of respiratory obstruction and infection may spread to the lungs.

Laryngotracheitis

General aspects

Various microbes may be involved, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), particularly in children.

Clinical features

Hoarseness, loss of voice and persistent cough are common. In children, partial laryngeal obstruction may cause noisy inspiration (stridor or croup) and is potentially dangerous.

General management

Symptomatic treatment only is available but ribavirin or palivizumab may be appropriate in RSV infection in infants who may otherwise subsequently develop bronchiolitis.

Dental aspects

Dental treatment should be deferred until after recovery. GA must be avoided, as it may exacerbate progression of infection to the lungs. Antimicrobials may be indicated for prophylaxis.

Bacterial Respiratory Tract Infections

Sinusitis

General aspects

Infection of the paranasal air sinuses (maxillary most commonly, but also ethmoid, sphenoid and frontal) is usually bacterial. It may be preceded by viral or other factors (Box 14.1).

Clinical features

Headache on wakening is typical, with pain worse on tilting the head or lying down; there is also nasal obstruction with mucopurulent nasal discharge (Table 14.3).

Table 14.3

| Sinus | Location of pain | Other features |

| Maxillary | Cheek and/or upper teeth, worsened by biting | Tenderness over antra |

| Frontal | Over frontal sinuses | Tenderness of sides of nose |

| Ethmoidal | Between eyes | Anosmia, eyelid swelling |

| Sphenoidal | Ear, neck, and top or centre of head | – |

General management

Diagnosis is from the history, plus tenderness over the sinus, dullness on transillumination, and radio-opacity or a fluid level on plain X-rays of the sinuses (sinus opacity may be due to mucosal thickening rather than infection, but a fluid level is highly suggestive of infection). Antral opacities in children can be difficult to evaluate since they are seen in up to 50% of healthy children under the age of 6 years. Computed tomography (CT) is now the standard care. Ultrasonography may be helpful. However, the gold standard for diagnosis remains sinus puncture and aspiration.

Sinusitis is classified as acute, chronic or recurrent.

In acute sinusitis, the bacteria most commonly incriminated are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Infection resolves spontaneously in about 50%, but analgesics are often indicated and antibiotics may be required if symptoms persist or there is a purulent discharge. Treatment is drainage using vasoconstrictor nasal drops, such as ephedrine or xylometazoline. Inhalations of warm, moist air, with benzoin, menthol or eucalyptus, may give symptomatic relief. In adults, a course of antimicrobials for longer than 7 days is indicated, using amoxicillin, ampicillin or co-amoxiclav (erythromycin or azithromycin, if penicillin-allergic), or a tetracycline, such as doxycycline, or clarithromycin. In children, high-dose amoxicillin, cefuroxime or co-amoxiclav is recommended especially if the child has received antibiotics during the 4–6 weeks prior to the infection.

Chronic sinusitis involves anaerobes, especially Porphyromonas (Bacteroides), and half are beta-lactamase producers. It may follow acute sinusitis, especially where there are local abnormalities, allergic rhinitis, or impaired defence mechanisms such as cystic fibrosis or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease. Gram-positive cocci and bacilli, as well as Gram-negative bacilli, may also be found – especially in HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients and those on prolonged endotracheal intubation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (up to 5% of cases are caused by Pseudomonas, especially in cystic fibrosis), Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae are also implicated. In immunocompromised persons, fungi may also be involved, including Mucor, Aspergillus or other species. Chronic sinusitis responds better to drainage by functional endoscopic surgical techniques (Fig. 14.2), plus antimicrobials, such as metronidazole with amoxicillin, erythromycin, clarithromycin or a cephalosporin.

Recurrent sinusitis should be treated with drainage, plus antimicrobials, and investigation to determine whether there is any underlying cause.

Dental aspects

Dental treatment should be deferred until after recovery. GA should be avoided, since there is often some respiratory obstruction and infection can spread to the lungs. Inhalational sedation may be impeded if the nasal airway is obstructed

Mycoses may infect the sinuses in immunocompromised persons (Ch. 20).

Otitis media

General aspects

Otitis media is a common middle-ear infection in children; 3 out of 4 experience it by the age of 3 years. Otitis media usually follows a viral URTI, often followed by bacterial superinfection. The most common bacterial pathogen is Streptococcus pneumoniae, followed by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis.

The most important predisposing factor is Eustachian tube (ET) dysfunction but immune defects and palatal dysfunction, such as cleft palate or submucous cleft, occasionally contribute. Interference with the ET mucosa by inflammatory oedema, adenoidal hypertrophy, negative intratympanic pressure or, rarely, a tumour facilitates direct extension of infections from the nasopharynx to the middle ear. Oesophageal contents regurgitated into the nasopharynx can enter the middle ear through the ET if it is patulous.

Clinical features

When the ears are infected, the ET becomes inflamed and swollen, the mucociliary pathways from the middle ear to the nasopharynx become paralysed or dysfunctional, and fluid is trapped inside the middle-ear cleft. The adenoids can also become infected and can block the openings of the ET, trapping air and fluid.

Acute otitis media is very painful, and is worse when the child is lying down. If the infection is not controlled, the eardrum ruptures and pus escapes through the perforation – otorrhoea – when there is an immediate decrease in pain. It may become evident that the child has diminished hearing in that ear. If ET dysfunction merely prevents the normal drainage of the middle-ear cleft, with or without previous acute infection, a condition referred to as otitis media with effusion or ‘glue ear’ becomes established. This also affects the hearing but is painless. In either case, temporary speech and language problems may become evident as a result of the hearing loss, but usually resolve spontaneously with time. Complications that are rare but can be serious include mastoiditis, meningitis, brain abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis, otitic hydrocephalus, facial palsy, cholesteatoma and tympanosclerosis.

General management

Medical treatment includes antibiotics (usually penicillin) and decongestants and/or antihistamines together with analgesia. If fluids from otitis media stay in the ear for several months, drainage by surgery, usually myringotomy (incision of the ear drum) and grommets (small drainage tubes placed in the incision), may be recommended. Adenoidectomy may also be indicated.

Malignant Neoplasms

Most head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas; other tumour types include lymphoepithelioma, spindle cell carcinoma, verrucous cancer, undifferentiated carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma. Use of computer guided surgery seems likely to improve outcomes, especially in patients whose anatomy has been altered.

Maxillary Antral Carcinoma

General aspects

Antral carcinoma is a rare neoplasm of unknown aetiology, seen mainly in older people.

Clinical features

From the outset, antral carcinoma presents with severe maxillary pain. As the tumour increases in size, the effects of expansion and infiltration of adjacent tissues also become apparent. There is intraoral alveolar swelling; ulceration of the palate or buccal sulcus; swelling of the cheek; unilateral nasal obstruction, often associated with a blood-stained discharge; obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct with consequent epiphora; hypoaesthesia or anaesthesia of the cheek in the infraorbital nerve distribution; proptosis and ophthalmoplegia consequent on invasion of the orbit; and trismus from infiltration of the muscles of mastication.

General management

Combinations of surgery and radiochemotherapy are usually required. Further details can be found in standard textbooks of otorhinolaryngology or maxillofacial surgery.

Neoplasms of the Pharynx

Cancer can develop in the nasopharynx (see below and Ch. 22), oropharynx (consisting of the base of tongue, the tonsillar region, soft palate and back of the oral cavity) or the hypopharynx. Patients with pharyngeal cancer are at greater risk of cancer elsewhere in the upper aerodigestive tract.

Factors that increase the risk of pharyngeal cancers include smoking (both tobacco and marijuana) or chewing tobacco; alcohol use; leukoplakia; human papillomavirus (oropharyngeal carcinoma); Epstein–Barr virus (nasopharyngeal carcinoma); anaemia (Paterson–Brown-Kelly syndrome); radiation; and immune defects.

Pharyngeal cancer is treated by one, or a combination, of radiotherapy, chemotherapy or surgery.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

General aspects

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may be associated with Epstein–Barr virus and dietary nitrosamines; it is especially common amongst the southern Chinese, some Inuit races and people in parts of North Africa, such as Tunisia. A similar tumour, undifferentiated carcinoma with lymphoid stroma, is one of the most common salivary gland cancers in Inuits and southern Chinese.

Clinical features

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma often remains asymptomatic for some time, as it rarely obstructs the nasopharynx. The ways in which it presents include:

General management

Treatment is usually by radiotherapy.

Laryngeal Carcinoma

Laryngeal cancer is found in the glottis, supraglottis or subglottis. It is most common in males, patients of both sexes over the age of 55 who smoke or drink alcohol, are infected with human papillomavirus or have immune defects. Risk factors may also include genetics (people of African descent are more likely than whites to be affected); a personal history of head and neck cancer; exposure to asbestos, sulphuric acid mist or nickel; or a diet low in vitamin A.

Clinical features

Symptoms and signs may include hoarseness, persistent sore throat, dysphagia, pain referred to the ear when swallowing, haemoptysis and cervical lymphadenopathy.

General management

Laryngoscopy, computed tomography (CT) and biopsy are required to confirm the diagnosis. Laryngeal cancer is treated by one, or a combination, of radiotherapy, chemotherapy or surgery. Laser surgery may be used for very early cancers of the larynx. A cordectomy removes the vocal cord. A supraglottic laryngectomy takes out only the supraglottis. A partial or hemi-laryngectomy removes only part of the larynx. A total laryngectomy removes the entire larynx and commits the patient to a permanent tracheostomy. Despite loss of part or all of the vocal apparatus, most patients are able to communicate by speech with or without further surgical procedures and electronic voice aids.

Oral and Oropharyngeal Carcinoma

See Chapter 22.

Salivary Neoplasms

General aspects

A wide range of different neoplasms can affect the salivary glands but most are uncommon; they are epithelial neoplasms, which present as unilateral swelling of the parotid and are benign. Most salivary gland neoplasms are seen in older people. There is a female predisposition.

Neoplasms in the major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular) are most commonly pleomorphic adenomas but others are usually monomorphic adenomas (such as adenolymphomas), mucoepidermoid tumours or acinic cell tumours. Neoplasms in the minor salivary glands are most commonly pleomorphic adenomas but carcinomas, particularly adenoid cystic carcinomas, account for about 50%.

Salivary gland tumours are more common in certain geographical locations. Inuits, for example, have an increased prevalence. The aetiology is unknown but there are various associations (Box 14.2). A suggested association of parotid tumours with mobile phone use is controversial.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses