Neurology

Key Points

• Neurological disorders often lead to significant disability

• Headaches are common and usually inconsequential but can signify life-threatening disease

• Stroke is a common cause of collapse, disability and death

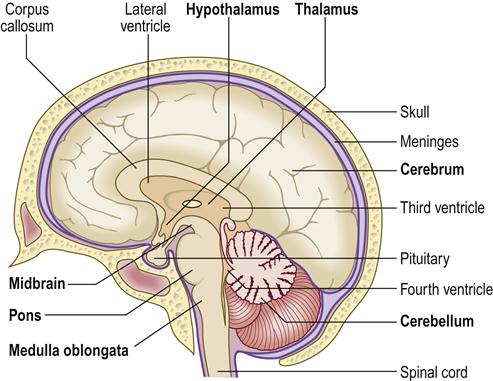

The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and spinal cord. The brain is the chief regulator of neuroendocrine, autonomic and immune systems, as well as behaviour. The brain contains the cerebral motor and sensory cortices essential for life, and other areas have specialized functions (Tables 10.1, 13.1 and 13.2; Figs 10.1, 13.1 and 13.2). Brain damage can lead to motor and/or sensory defects, variable disability, or even to loss of consciousness and/or death.

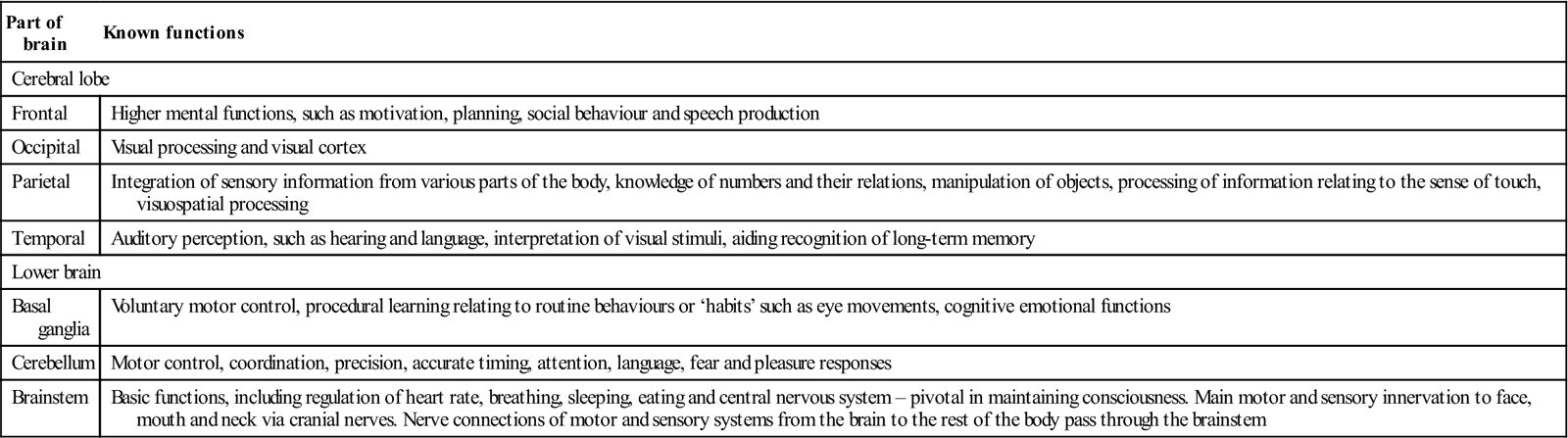

Table 13.1

Functions of main parts of the brain

< ?comst?>

| Part of brain | Known functions |

| Cerebral lobe | |

| Frontal | Higher mental functions, such as motivation, planning, social behaviour and speech production |

| Occipital | Visual processing and visual cortex |

| Parietal | Integration of sensory information from various parts of the body, knowledge of numbers and their relations, manipulation of objects, processing of information relating to the sense of touch, visuospatial processing |

| Temporal | Auditory perception, such as hearing and language, interpretation of visual stimuli, aiding recognition of long-term memory |

| Lower brain | |

| Basal ganglia | Voluntary motor control, procedural learning relating to routine behaviours or ‘habits’ such as eye movements, cognitive emotional functions |

| Cerebellum | Motor control, coordination, precision, accurate timing, attention, language, fear and pleasure responses |

| Brainstem | Basic functions, including regulation of heart rate, breathing, sleeping, eating and central nervous system – pivotal in maintaining consciousness. Main motor and sensory innervation to face, mouth and neck via cranial nerves. Nerve connections of motor and sensory systems from the brain to the rest of the body pass through the brainstem |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

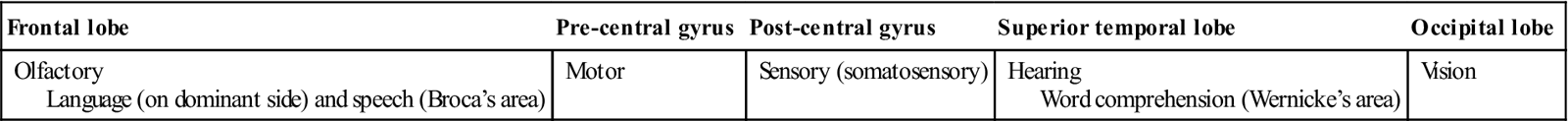

Table 13.2

Location of the main functions in the cerebral cortex

< ?comst?>

| Frontal lobe | Pre-central gyrus | Post-central gyrus | Superior temporal lobe | Occipital lobe |

| Olfactory Language (on dominant side) and speech (Broca’s area) |

Motor | Sensory (somatosensory) | Hearing Word comprehension (Wernicke’s area) |

Vision |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

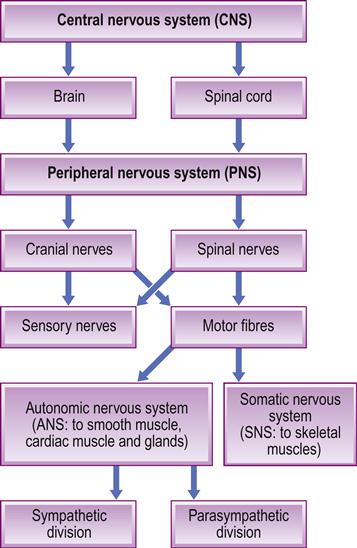

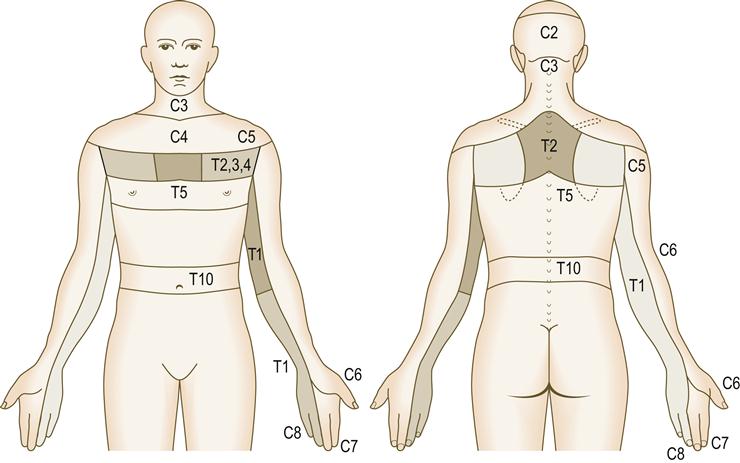

The CNS controls the peripheral nervous system (PNS), which consists of the somatic (SNS) and (ANS) autonomic nervous systems, and extends to the limbs and organs (Fig. 13.3). The SNS is under conscious control and is responsible for receiving external stimuli and for coordinating movement. The ANS consists of the sympathetic, parasympathetic and enteric nervous systems. The sympathetic system responds to danger or stress by release of adrenaline (epinephrine) – increasing anxiety, cardiac rate and output, and other physiological changes. The parasympathetic system is responsible for slowing the heart, dilating blood vessels, and stimulating digestive and genitourinary systems. The enteric nervous system controls digestion in the gastrointestinal tract.

The core components of the nervous system are neurons. Action potentials travel down the neuronal axon to open calcium (Ca2+) channels in the plasma membrane, triggering the exocytosis of vesicles containing neurotransmitters, which affect a receiving cell. The main neurotransmitters are acetylcholine (ACh) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), but there are many others (see Tables 13.1 and 10.3).

ACh at excitatory synapses depolarizes the post-synaptic membrane, causing an excitatory post-synaptic potential and an action potential in the post-synaptic cell. ACh is released at the terminals of all motor neurons activating skeletal muscle, all pre-ganglionic neurons of the ANS and post-ganglionic neurons of the parasympathetic system. ACh also mediates transmission at brain synapses involved in acquisition of short-term memory.

Amino acids such as glutamic acid are involved in CNS transmission at excitatory synapses and are essential for long-term potentiation, a form of memory. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at inhibitory synapses hyperpolarizes the post-synaptic membrane, causing an inhibitory post-synaptic potential.

Neurological Disease

Patients whose symptoms have a neurological basis are relatively common. Dental professionals may well be involved in the care of these people, especially of those with the most important brain disorders, such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy, cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs; strokes) and facial palsy. The most common neurological complaints are shown in Box 13.1. The role of stress is discussed in Chapter 10.

Orofacial pain is common and may have a neurological cause. Patients with head or maxillofacial injuries may have brain damage with impaired ocular movements or pupil reactions and loss of the sense of smell (anosmia). Dental professionals should therefore be able to examine and recognize gross neurological abnormalities, and especially problems involving the cranial nerves – particularly the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, vagal and hypoglossal nerves.

Neurological Evaluation

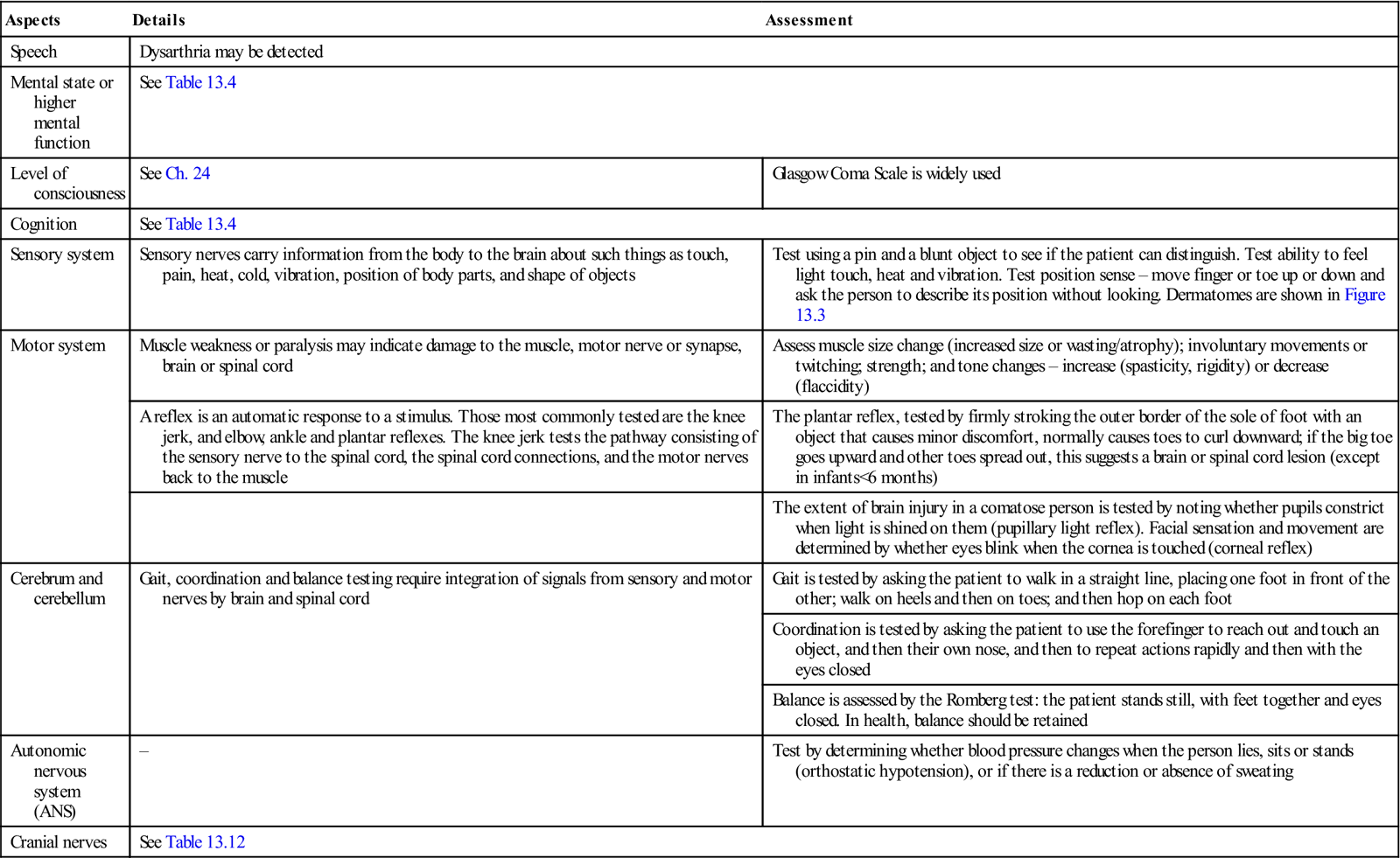

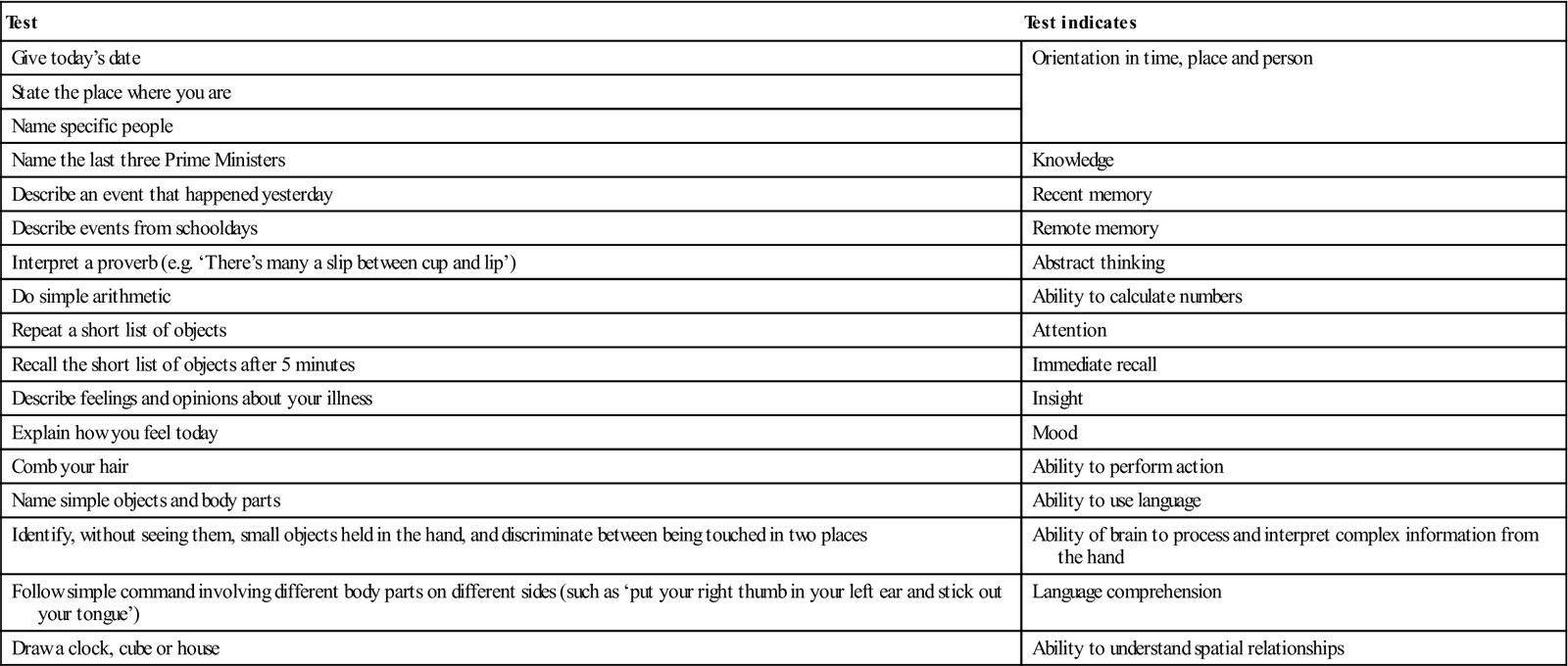

The nervous system may need to be evaluated, as in Table 13.3. Mental status can be assessed using a standard screening test, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Folstein test (simple questions and problems in a number of areas: the time and place of the test, repeating lists of words, arithmetic, language use and comprehension, and basic motor skills). Testing can also be achieved as shown in Table 13.4.

Table 13.3

< ?comst?>

| Aspects | Details | Assessment |

| Speech | Dysarthria may be detected | |

| Mental state or higher mental function | See Table 13.4 | |

| Level of consciousness | See Ch. 24 | Glasgow Coma Scale is widely used |

| Cognition | See Table 13.4 | |

| Sensory system | Sensory nerves carry information from the body to the brain about such things as touch, pain, heat, cold, vibration, position of body parts, and shape of objects | Test using a pin and a blunt object to see if the patient can distinguish. Test ability to feel light touch, heat and vibration. Test position sense – move finger or toe up or down and ask the person to describe its position without looking. Dermatomes are shown in Figure 13.3 |

| Motor system | Muscle weakness or paralysis may indicate damage to the muscle, motor nerve or synapse, brain or spinal cord | Assess muscle size change (increased size or wasting/atrophy); involuntary movements or twitching; strength; and tone changes – increase (spasticity, rigidity) or decrease (flaccidity) |

| A reflex is an automatic response to a stimulus. Those most commonly tested are the knee jerk, and elbow, ankle and plantar reflexes. The knee jerk tests the pathway consisting of the sensory nerve to the spinal cord, the spinal cord connections, and the motor nerves back to the muscle | The plantar reflex, tested by firmly stroking the outer border of the sole of foot with an object that causes minor discomfort, normally causes toes to curl downward; if the big toe goes upward and other toes spread out, this suggests a brain or spinal cord lesion (except in infants<6 months) | |

| The extent of brain injury in a comatose person is tested by noting whether pupils constrict when light is shined on them (pupillary light reflex). Facial sensation and movement are determined by whether eyes blink when the cornea is touched (corneal reflex) | ||

| Cerebrum and cerebellum | Gait, coordination and balance testing require integration of signals from sensory and motor nerves by brain and spinal cord | Gait is tested by asking the patient to walk in a straight line, placing one foot in front of the other; walk on heels and then on toes; and then hop on each foot |

| Coordination is tested by asking the patient to use the forefinger to reach out and touch an object, and then their own nose, and then to repeat actions rapidly and then with the eyes closed | ||

| Balance is assessed by the Romberg test: the patient stands still, with feet together and eyes closed. In health, balance should be retained | ||

| Autonomic nervous system (ANS) | – | Test by determining whether blood pressure changes when the person lies, sits or stands (orthostatic hypotension), or if there is a reduction or absence of sweating |

| Cranial nerves | See Table 13.12 | |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Table 13.4

< ?comst?>

| Test | Test indicates |

| Give today’s date | Orientation in time, place and person |

| State the place where you are | |

| Name specific people | |

| Name the last three Prime Ministers | Knowledge |

| Describe an event that happened yesterday | Recent memory |

| Describe events from schooldays | Remote memory |

| Interpret a proverb (e.g. ‘There’s many a slip between cup and lip’) | Abstract thinking |

| Do simple arithmetic | Ability to calculate numbers |

| Repeat a short list of objects | Attention |

| Recall the short list of objects after 5 minutes | Immediate recall |

| Describe feelings and opinions about your illness | Insight |

| Explain how you feel today | Mood |

| Comb your hair | Ability to perform action |

| Name simple objects and body parts | Ability to use language |

| Identify, without seeing them, small objects held in the hand, and discriminate between being touched in two places | Ability of brain to process and interpret complex information from the hand |

| Follow simple command involving different body parts on different sides (such as ‘put your right thumb in your left ear and stick out your tongue’) | Language comprehension |

| Draw a clock, cube or house | Ability to understand spatial relationships |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

If cognitive functions seem unaffected, there is no related complaint, and the patient appears, behaves and supplies a history normally, formal cognitive evaluation is not required.

Headaches and Orofacial Pain

Pain is broadly divided into nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain.

Nociceptive pain is caused by actual or potential damage to tissues (e.g. trauma, cut, burn). Nerve endings become activated or damaged by the injury, with pain that tends to be sharp or aching and is often eased by traditional analgesics such as paracetamol (acetaminophen), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids.

Neuropathic pain (neuralgia) is a pain arising from nerve signal problems and is often persistent, with features such as burning, stabbing, aching or electric shock-like qualities. Neuropathic pain may be experienced in:

■ cancer

■ human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

■ idiopathic (atypical) facial pain

■ phantom pain (follows surgery)

Related to these pains there may also be phenomena including:

■ Allodynia – Pain starts, or worsens, with a touch or stimulus that would not normally cause pain.

■ Paraesthesia – Unpleasant or painful feelings are experienced, even when there is no stimulus.

Neuropathic pain is less likely than nociceptive pain to be eased by traditional analgesics but is often improved by:

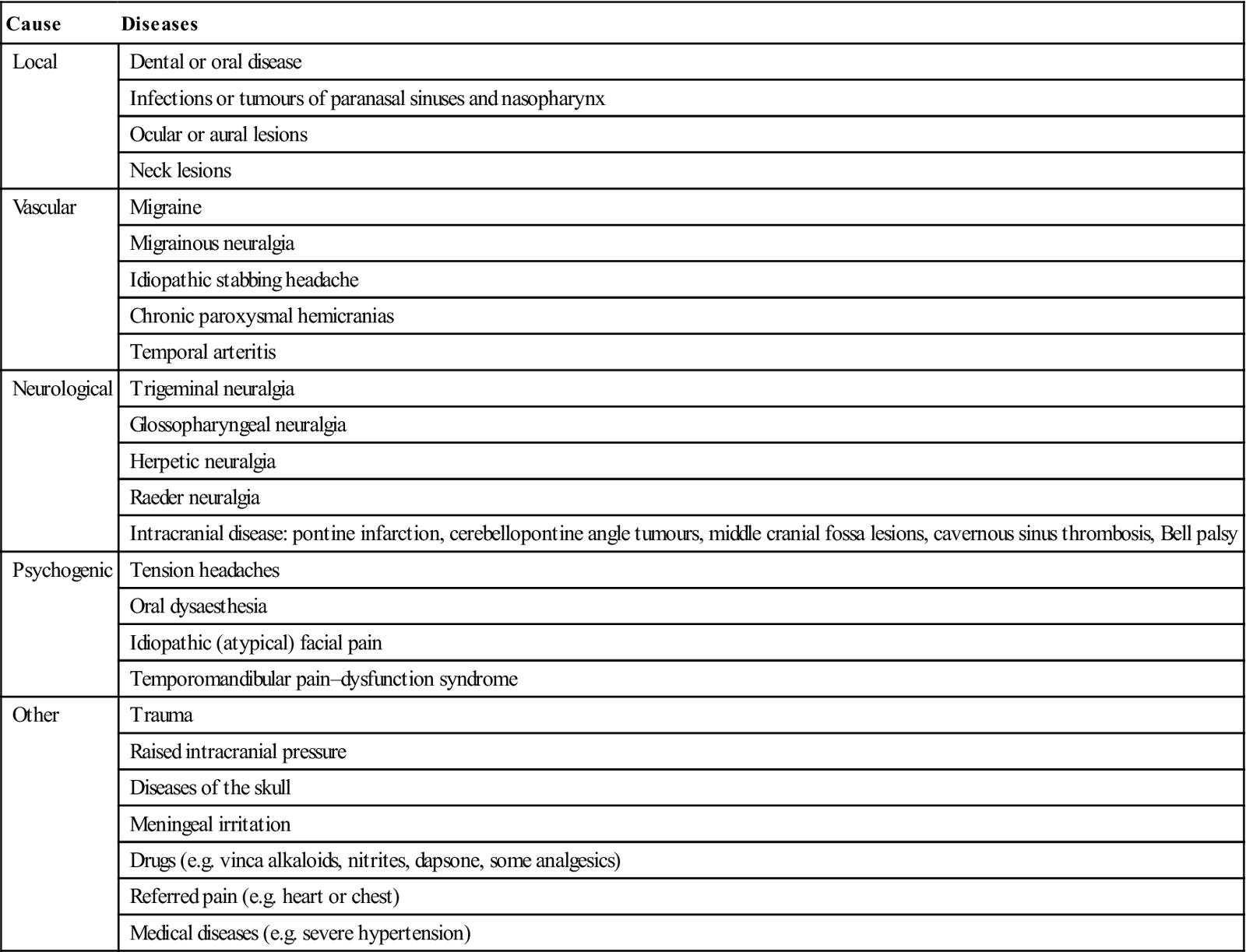

Pain receptors can be stimulated by stress, muscular tension, dilated blood vessels and other triggers. Headache and orofacial pain are the most common neurological complaints; they are often chronic and are mainly caused by local disease, vascular disease, referred pain, neurological disorders or psychogenic disorders (Table 13.5 and Box 13.2). Headaches can also occasionally herald serious brain disorders, such as tumour, infection or bleeding (Box 13.3). Features suggesting serious or life-threatening headaches are shown in Box 13.4.

Table 13.5

Causes of headache and orofacial pain

< ?comst?>

| Cause | Diseases |

| Local | Dental or oral disease |

| Infections or tumours of paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx | |

| Ocular or aural lesions | |

| Neck lesions | |

| Vascular | Migraine |

| Migrainous neuralgia | |

| Idiopathic stabbing headache | |

| Chronic paroxysmal hemicranias | |

| Temporal arteritis | |

| Neurological | Trigeminal neuralgia |

| Glossopharyngeal neuralgia | |

| Herpetic neuralgia | |

| Raeder neuralgia | |

| Intracranial disease: pontine infarction, cerebellopontine angle tumours, middle cranial fossa lesions, cavernous sinus thrombosis, Bell palsy | |

| Psychogenic | Tension headaches |

| Oral dysaesthesia | |

| Idiopathic (atypical) facial pain | |

| Temporomandibular pain–dysfunction syndrome | |

| Other | Trauma |

| Raised intracranial pressure | |

| Diseases of the skull | |

| Meningeal irritation | |

| Drugs (e.g. vinca alkaloids, nitrites, dapsone, some analgesics) | |

| Referred pain (e.g. heart or chest) | |

| Medical diseases (e.g. severe hypertension) |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Some headaches have quite specific and less serious precipitating factors (Table 13.6); foods such as alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, cheeses and nuts can cause headaches in some people and may trigger migraine. About 50% of patients seen in headache clinics are thought to suffer from muscle contraction (tension) headaches, which appear to involve the tightening or tensing of facial and neck muscles because of stress (see Ch. 10 and below). Virtually all types of headache are influenced, at least to some extent, by stress, emotional factors and individual personalities.

Table 13.6

Some less serious causes of headache

| Conditions | Causes |

| Chinese restaurant syndrome | Monosodium glutamate |

| Hangover headache | Acetaldehyde |

| Hot dog headache | Nitrites/nitrates |

| Post-coital headache | Intercourse |

| Vitamin A-induced headache | Vitamin A |

Local Causes of Orofacial Pain

The mouth

Oral causes of facial pain (e.g. pulpitis, apical periodontitis, periodontal abscesses, pericoronitis and various intraosseous lesions) are common and are discussed in other texts.

The sinuses and nasopharynx

Sinusitis causes localized pain. In acute maxillary or frontal sinusitis, local pain and tenderness (but not swelling), with radio-opacity of the affected sinuses, usually follow a cold (Ch. 14).

Tumours of sinuses or nasopharynx can also cause facial pain. These are rare, usually carcinomas, and involve trigeminal nerve branches; they may cause pain simulating pain–dysfunction syndrome. They can remain undetected until late in their course.

Eagle syndrome, due to calcification of the stylohyoid ligament, may be a rare cause of pain on chewing, swallowing or turning the head. The elongated styloid process may be visualized radiographically, and palpation of it in the wall of the pharynx causes intense pain. The stylohyoid process can be shortened surgically, but regrowth and relapse are common.

The eyes

Glaucoma (raised intraocular pressure) may cause pain in and around the orbit. Disorders of refraction can cause frontal headaches. Retrobulbar neuritis (e.g. in multiple sclerosis) can cause pain in and around the orbit.

The ears

Pharyngeal or middle ear disease may cause headaches. Oral disease can rarely cause pain referred to the ear; the classic picture is that of the older man with tongue cancer whose complaint is earache.

The neck

Cervical vertebral disease occasionally causes headache or pain referred to the face and may aggravate tension headaches. Nerve block with local anaesthesia (LA) may temporarily relieve this pain. Carotidynia is unilateral pain arising from the cervical carotid artery that radiates to the ipsilateral face and ear, and sometimes to the head; it is associated with carotid artery tenderness and overlying soft tissue swelling, and is responsive to corticosteroids.

Vascular Causes of Facial Pain

Vasomotor states are responsible for certain headaches; either widening or narrowing of extracranial and intracranial arteries may produce pain. Both vasodilatation and neurogenic inflammation are under the influence of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5HT); the 5HT1B receptor controls vasodilatation, whereas 5HT1D regulates neurogenic inflammation.

Serotonin agonists, such as ergotamine and triptans, can prevent neurogenic inflammation.

Migraine

Further information on migraine may be found at: http://www.disabled-world.com/health/neurology/migraine/ (accessed 30 September 2013).

General aspects

Migraine is a recurrent headache combined with autonomic disturbances, affecting over 14% of women and 7% of men. The prodrome is usually accompanied by diminished cerebral blood flow, possibly the result of a neuronal trigger mechanism in the trigeminovascular nucleus, but the headache itself is usually associated with increased cerebral and extracranial blood flow, possibly caused by serotonin adsorbed to blood vessel walls, since platelet serotonin rises before a migraine headache. This may cause the trigeminal nerve to release neuropeptides; the combination of serotonin and bradykinin may cause blood vessels to become dilated and inflamed.

Clinical features

Migraine triggers can include:

■ weather, season, altitude, or time zone changes

■ drugs (e.g. cimetidine, fenfluramine, nifedipine and theophylline)

■ mealtime changes, skipped meals or fasting

■ intense physical exertion, including sexual activity

■ tobacco

■ bright lights, loud noises or strong odours

■ menstrual cycle hormone changes

■ stress, anxiety, or relaxation after stress

■ caffeine (excess or withdrawal)

■ nitrates, such as in hot dogs and lunch meats

■ monosodium glutamate (MSG), a flavour enhancer in fast foods, broths, seasonings and spices

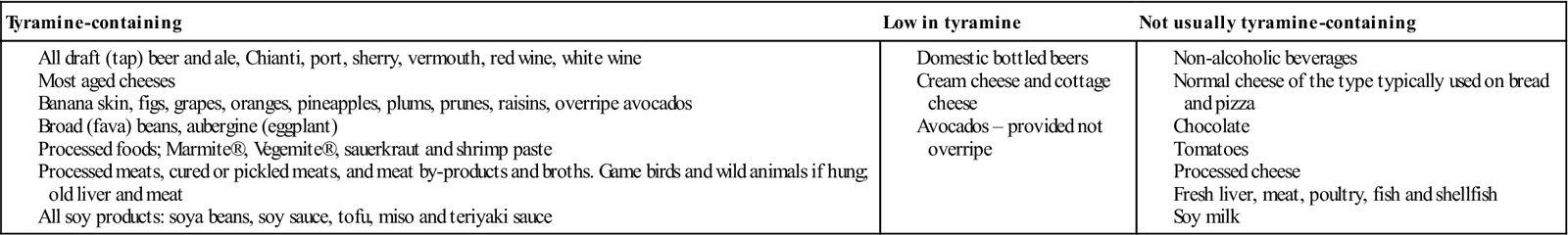

■ tyramine, such as in aged cheeses, soy products, broad (fava) beans, hard sausages, smoked fish and Chianti wine. The highest levels of tyramine are in aged cheeses, spoiled meats, aged and cured meats, Marmite®, sauerkraut, fermented soybean products, broad bean pods and draft (tap) beer, but there is little or no tyramine in non-alcoholic beverages, breads, fats, cottage cheese, ricotta, cream cheese, soft farmer’s cheese, mozzarella cheese, processed cheese slices, sour cream, yogurt, milk, eggs, tomatoes, fresh meat, poultry, fish, shellfish and soy milk (Table 13.7; see also http://www.headaches.org/pdf/Diet.pdf, accessed 30 September 2013).

Table 13.7

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Large quantities of nuts (peanuts, coconuts and brazil nuts) may trigger hypertensive reactions and headaches, but not via tyramine.

The fact that migraine attacks are more frequent at weekends, for example, should not be interpreted as excluding stress, as there is no doubt that some find the company and demands of their families more stressful than their work. Going away on holiday (Freud’s Reisefieber – ‘travel fever’) is also highly stressful for many.

Several types of migraine are recognized (Table 13.8); migraine without aura is the most frequent – presenting with unilateral headache – but migraine with aura is the most readily recognizable.

Table 13.8

< ?comst?>

| Type/subtype | Clinical features |

| Migraine | |

| Status | Intense pain that usually lasts longer than 72 h |

| Abdominal | Abdominal pain without a gastrointestinal cause (lasts up to 72 h), nausea, vomiting, and flushing or paleness. Children who have abdominal migraine often develop typical migraine as they age |

| Headache-free | Aura without headache |

| Migraine without aura | Tiredness or mood changes the day before the headache, which may be on one or both sides of head. Nausea, vomiting and also sensitivity to light |

| Classic | Unilateral headache preceded by an aura (a neurological phenomenon) experienced 10–30 min before the headache. Most auras are visual (bright shimmering lights around objects or at the edges of the field of vision or zigzag lines, castles, wavy images, or hallucinations). Other patients have temporary vision loss. Non-visual auras include motor weakness, speech or language abnormalities, dizziness, vertigo, and tingling or numbness of face, tongue or extremities |

| Hemiplegic | Often familial; hemiparesis may outlast headache by several days; may rarely cause facial palsy |

| Ophthalmoplegic | Affects children (boys) mainly. As headache progresses, eyelid droops and eye movements become paralysed. Ptosis may persist for days or weeks |

| Vertebrobasilar | Affects adolescent girls mainly. Aura associated with ataxia, vertigo, diplopia; headache usually occipital; there may be loss of consciousness at the onset |

| Complicated | Any form of migraine complicated by residual neurological defect after attack |

| Migrainous neuralgia | |

| Classic | Pain typically around the eye, often with visible effects of vasodilatation |

| Facial migraine | Affects lower face (lower-half migraine or carotidynia). Episodes may occur several times weekly and last a few minutes to hours. Deep, dull, aching and sometimes piercing pain in the jaw or neck. There is usually tenderness and swelling over the carotid artery |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses