Medical emergencies

Key Points

This chapter is focused on the main diagnostic and management issues in emergency management; fuller discussion of these conditions may be found in the relevant chapters and the controversies in this area are discussed in the references. The expanded knowledge base of medicine, and effective new technologies, techniques and drugs have allowed patients, who in earlier times would have succumbed, to remain alive and live to much greater ages; such patients in particular may be prone to medical emergencies. Collapse and other emergencies are a cause of concern for all involved (Box 1.1).

In general terms, health-care professionals (HCPs) should develop strategies to identify patients at risk of emergencies, assess the severity of those risks and, where necessary, recognize the need for help and be able to seek advice from a colleague with special competence in the relevant fields. All need to contend with the increasing variety of medical problems, particularly as they are aware that they face a growing risk of litigation if they do not keep themselves familiar with current knowledge, in line with the increasing acceptance of the need for continuing professional development (CPD).

There are few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available to provide evidence for the various practices, and so many of the recommendations have to be based on consensus. The comments and recommendations herein should be used as guidelines to care, not commandments.

Annual theoretical and practical training of all clinical staff is required. Clinical staff have an obligation to be conversant with the current Resuscitation Council (UK) guidelines (2012) (see Further reading). The UK General Dental Council (GDC), in Standards for the dental team (2013), states that all dental professionals are responsible for putting patients’ interests first and for acting to protect them. Central to this responsibility is the need to ensure that HCPs are able to deal with medical emergencies that may arise. All members of the dental team need to know their roles in the event of an emergency. The GDC guidance, Principles of dental team working (2005), states that dental staff who employ, manage or lead a team should make sure that:

The GDC has stipulated that 10 hours of training and retraining in emergency management is a mandatory requirement of CPD in every 5-year period.

Emergencies are rare. A medical emergency occurring in dental practice is most likely to be the result of an acute deterioration of a known medical condition. It may pose an immediate threat to an individual’s life and needs rapid intervention. It is best prevented! The most common medical emergency is the simple faint. Other common emergencies include fitting in an epileptic patient, angina pectoris (ischaemic chest pain), hypoglycaemia in a diabetic patient and haemorrhage. Myocardial infarction and cardiopulmonary arrest are more immediately dangerous (Box 1.2).

Preventing Emergencies

Emergency management algorithms are of paramount importance and dental employers are ultimately responsible for the performance of their staff as regards delivery.

Confidence and satisfactory management of emergencies can be improved by the following measures:

■ Never practising dentistry without another competent adult in the room.

■ Having a readily accessible emergency drugs box and equipment that is checked on a weekly basis (Tables 1.1 and 1.2; Figs 1.1–1.3).

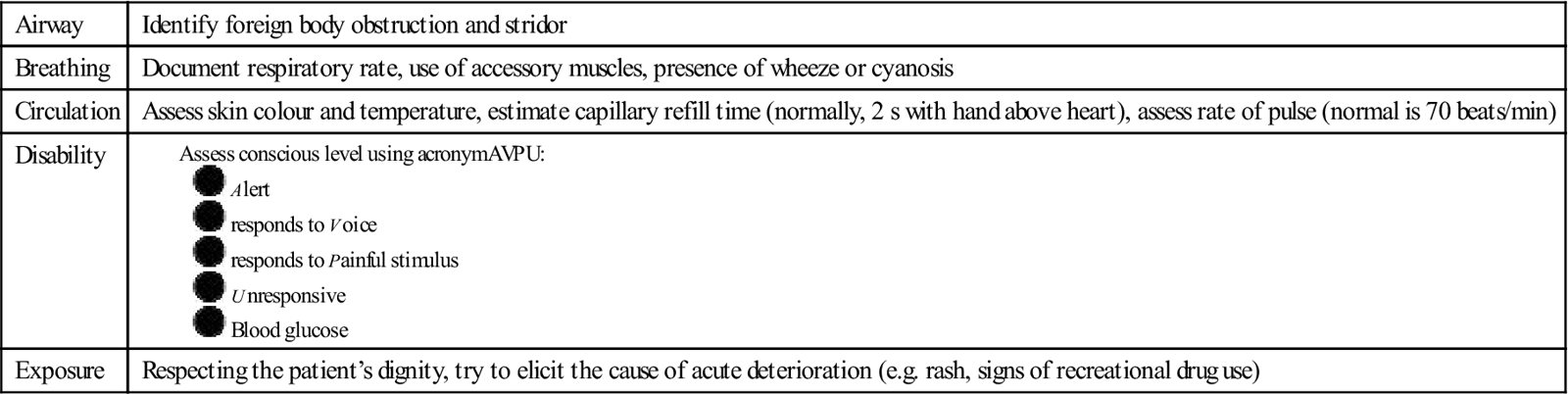

Table 1.1

Suggested minimal equipment for emergency use in dentistrya

< ?comst?>

| Equipment | General comments | Detail |

| Oxygen (O2) delivery | Portable apparatus for administering oxygen | Two portable oxygen cylinders (‘D’ size) with pressure reduction valves and flow meters. Cylinders should be of sufficient size to be easily portable but also to allow for adequate flow rates (e.g. 10 L/min), until the arrival of an ambulance or full recovery of the patient. A full ‘D’ size cylinder contains 340 L of oxygen and should allow a flow rate of 10 L/min for up to 30 min. Two such cylinders may be necessary to ensure the oxygen supply does not fail |

| Oxygen face mask (non-rebreathe type) with tube | ||

| Basic set of oropharyngeal airways (sizes 1, 2, 3 and 4) | ||

| Pocket mask with oxygen port | ||

| Self-inflating bag valve mask (BVM; 1-L size bag), where staff have been appropriately trained | ||

| Variety of well-fitting adult and child face masks for attaching to self-inflating bag | ||

| Portable suction | Portable suction with appropriate suction catheters and tubing (e.g. Yankauer sucker) | |

| Spacer device for inhalation of bronchodilators | ||

| Automated external defibrillator (AED) | All clinical areas should have immediate access to an AED (collapse-to-shock time<3 min) | |

| Automated blood glucose measuring device | ||

| Equipment for administering drugs intramuscularly | Single-use sterile syringes (2-mL and 10-mL sizes) and needles (19 and 21 sizes) | Drugs as in Table 1.2 |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

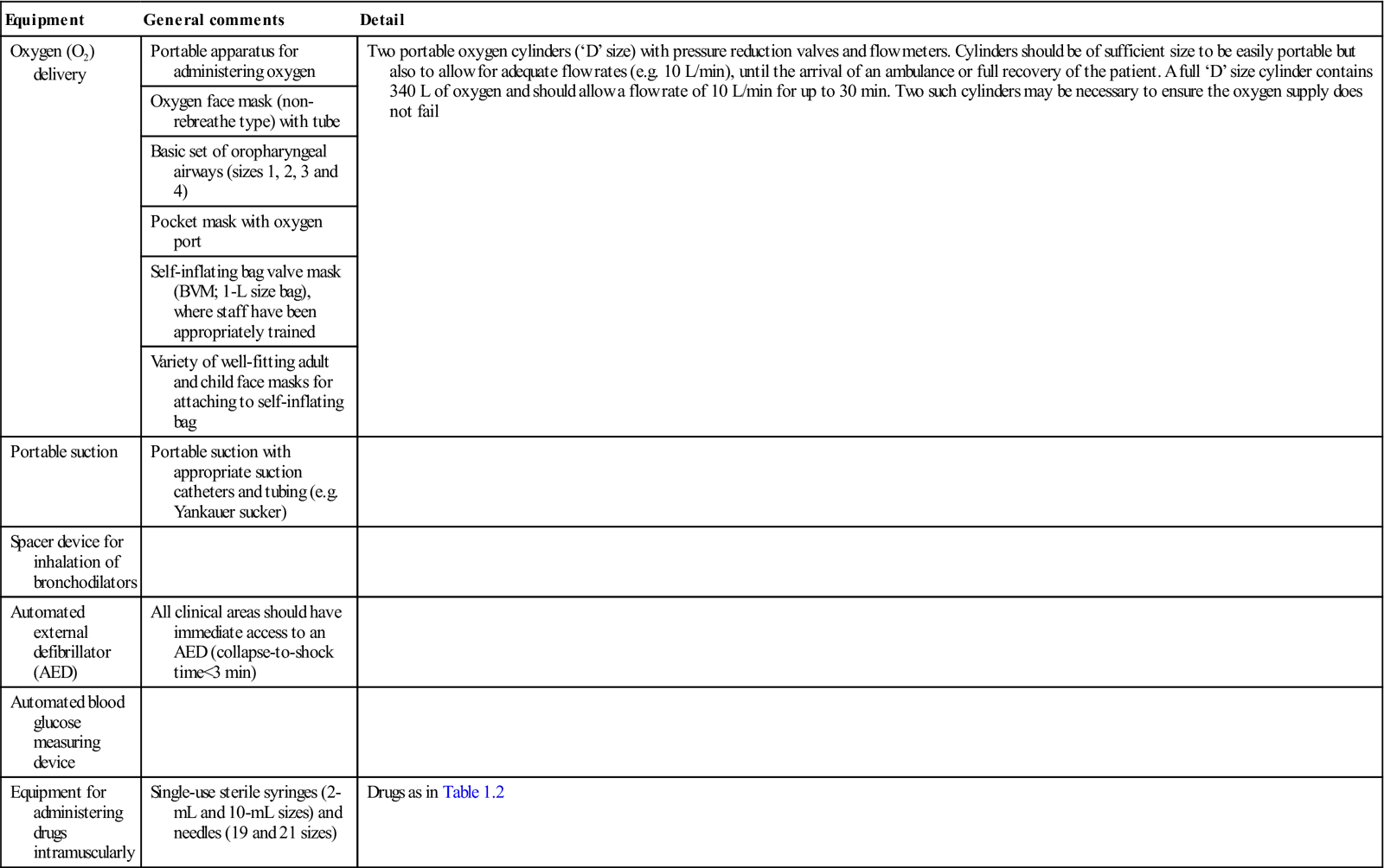

Table 1.2

Suggested minimal drugs for emergency use in dentistrya

< ?comst?>

| Emergency | Drugs required | Dosages for adults |

| Anaphylaxis | Adrenaline (epinephrine) injection 1:1000, 1 mg/mL | Intramuscular adrenaline (0.5 mL of 1 in 1000 solution) |

| Repeat at 5 min if needed | ||

| Hypoglycaemia | Oral glucose solution/tablets/gel/powder (e.g. GlucoGel®, formerly known as Hypostop® gel [40% dextrose]) | Proprietary non-diet drink or 5 g glucose powder in water |

| Glucagon injection 1 mg (e.g. GlucaGen HypoKit) | Intramuscular glucagon 1 mg | |

| Acute exacerbation of asthma | (β2 agonist) | Salbutamol aerosol |

| Salbutamol aerosol inhaler 100 mcg/activation | Activations directly or up to six into a spacer | |

| Status epilepticus | Buccal or intranasal midazolam 10 mg/mL | Midazolam 10 mg |

| Angina | Glyceryl trinitrateb spray 400 mcg/metered activation | Glyceryl trinitrate, two sprays |

| Myocardial infarct | Dispersible aspirin 300 mg | Dispersible aspirin 300 mg (chewed) |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

aAfter Resuscitation Council (2012). No corticosteroid is included.

All this is even more important when conscious sedation (CS) is used, when invasive or painful procedures are planned, or when medically complex individuals are being treated. ‘Forewarned is forearmed,’ and dental professionals must ensure that medical and drug histories are updated at each visit prior to initiating treatment. It is suggested that disease severity should be assessed using a risk stratification system – for example, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification (Chs 2 and 3) – as this may help identify high-risk individuals.

Few emergencies can be treated definitively in the dental clinic. The role of the dental team is one of support and considered intervention using algorithms that can ‘do no harm’. Previously, it has been suggested that 20 or more drugs should be available to the dental professional for the management of emergencies but this is impractical, may be a source of confusion and, if a drug is incorrectly administered, may be life-threatening.

The Resuscitation Council recommendations for equipment and drugs are detailed in Tables 1.1 and 1.2. Other agents (e.g. the midazolam antagonist flumazenil) and equipment (e.g. a pulse oximeter) are needed if CS is administered.

General anaesthesia (GA) must be undertaken only by anaesthetists and where advanced life support (ALS) is available.

Resuscitation and Emergencies

The GDC does not have any guidelines on resuscitation but would refer registrants to the Resuscitation Council, which does have relevant guidance. Full details are available at http://www.gdc-uk.org/Dentalprofessionals/Standards/Pages/home.aspx (accessed 30 September 2013).

The GDC’s Principles of dental team working (2005) covers medical emergencies.

Managing Emergencies

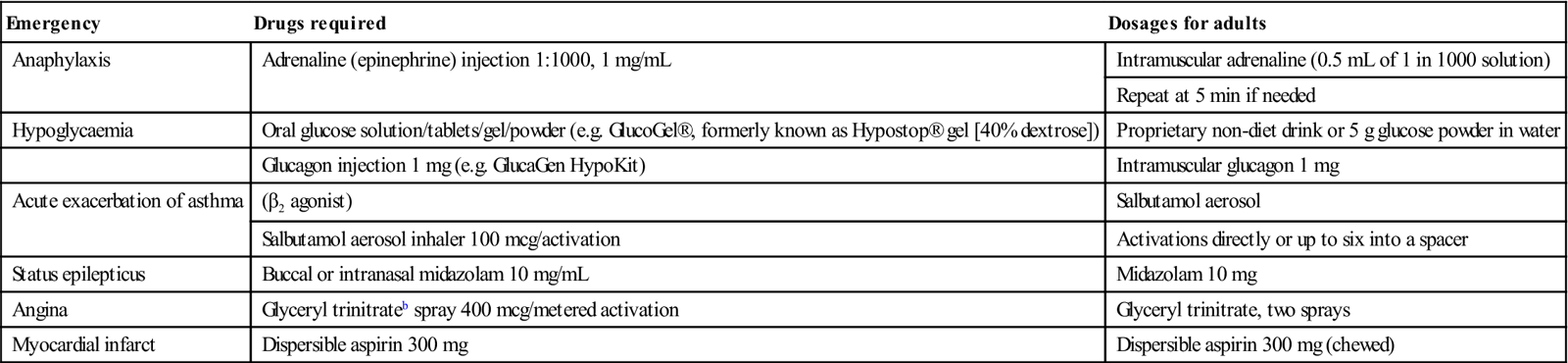

For all medical emergencies, a structured approach to assessment and reassessment prevents any symptoms and signs being missed and any incorrect diagnoses being made. The sequence is best remembered as ‘ABCDE’ (Box 1.3). ‘Drs ABC’ highlights the sequence:

People who collapse should be put in the ‘recovery position’ to maintain a clear airway UNLESS there could be a neck injury, such as after a fall or road traffic accident.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Dental staff should be trained in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) so that, in the event of cardiac arrest, they should be able to:

Hands-only CPR

Emergency Procedure

■ Assess the patient – ABCDE (as Box 1.3) – and give oxygen if appropriate

Monitor – reassess ABCDE regularly, attach an AED if appropriate

Oxygen – 15 L/min through a non-rebreathe mask

Verify – check that emergency services are coming

Emergency action – correct positioning and drug administration.

Intramuscular (i.m.) injection is used nowadays for giving most emergency drugs. The most accessible site in a clothed patient sitting in a dental chair is the lateral aspect of the thigh. There the vastus lateralis is a large muscle with no large nerves or arteries running through it. In an emergency, the injection can be administered through clothing. The mid-point between the pelvis and the knee is the preferred site.

The Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System (AMPDS) is a unified system that sends appropriate aid to medical emergencies, including systematized caller interrogation and pre-arrival instructions. AMPDS works on the following response categories:

This may well be linked to a performance targeting system where calls must be responded to within a given time period. For example, in the UK, calls rated as ‘A’ on AMPDS aim to have a responder on scene within 8 minutes.

The ‘ABCDE’ approach to the sick patient

The ‘ABCDE’ approach to the sick patient is outlined at http://www.resus.org.uk/pages/MEdental.pdf by the UK Resuscitation Council (2006, updated 2012; accessed 30 September 2013). Appendix (i), which cannot be bettered, and states:

Dental Practitioners, Dental Care Professionals and their staff should be familiar with standard resuscitation procedures as recommended by the Resuscitation Council (UK). In all circumstances it is advisable to call for medical assistance as soon as possible by dialling 999 and summoning an ambulance.

Early recognition of the ‘sick’ patient is to be encouraged. Pre-empting any medical emergency by recognising an abnormal breathing pattern, an abnormal patient colour or abnormal pulse rate, allows appropriate help to be summoned, e.g. ambulance, prior to any patient collapse occurring. A systematic approach to recognising the acutely ill patient based on the ‘ABCDE’ principles is recommended. Accurate documentation of the patient’s medical history should further allow those ‘at risk’ of certain medical emergencies to be identified in advance of any proposed treatment. The elective nature of most dental practice allows time for discussion of medical problems with the patient’s general medical practitioner where necessary. In certain circumstances this may lead to a postponement of the treatment indicated or a recommendation that such treatment be undertaken in hospital.

3. Continually reassess, starting with Airway, if there is further deterioration.

4. Assess the effects of any treatment given.

7. Organise your team and communicate effectively.

9. Remember – it can take a few minutes for treatment to work.

■ In an emergency, stay calm. Ensure that you and your staff are safe.

■ Look at the patient generally to see if they ‘look unwell’.

Airway (A)

Airway obstruction is an emergency.

1. Look for the signs of airway obstruction:

◆ In partial airway obstruction, air entry is diminished and usually noisy:

Inspiratory ‘stridor’ is caused by obstruction at the laryngeal level or above.

Gurgling suggests there is liquid or semi-solid foreign material in the upper airway.

Snoring arises when the pharynx is partially occluded by the tongue or palate.

2. Airway obstruction is an emergency:

◆ In most cases, only simple methods of airway clearance are needed:

Airway opening manœuvres – head tilt/chin lift or jaw thrust.

Consider simple airway adjuncts, e.g. oropharyngeal airway.

Breathing (B)

During the immediate assessment of breathing, it is vital to diagnose and treat immediately life-threatening breathing problems, e.g. acute severe asthma.

Circulation (C)

Simple faints or vasovagal episodes are the most likely cause of circulation problems in general dental practice. These will usually respond to laying the patient flat and, if necessary, raising the legs (see Appendix (ii) Syncope). The systematic ABCDE approach to all patients will ensure that other causes are not missed.

1. Look at the colour of the hands and fingers: are they blue, pink, pale or mottled?

2. Assess the limb temperature by feeling the patient’s hands: are they cool or warm?

(See Appendix (ii) Cardiac Emergencies.)

Disability (D)

Common causes of unconsciousness include profound hypoxia, hypercapnia (raised carbon dioxide levels), cerebral hypoperfusion (low blood pressure), or the recent administration of sedatives or analgesic drugs.

1. Review and treat the ABCs: exclude hypoxia and low blood pressure.

2. Check the patient’s drug record for reversible drug-induced causes of depressed consciousness.

3. Examine the pupils (size, equality and reaction to light).

6. Nurse unconscious patients in the recovery position if their airway is not protected.

Exposure (E)

To assess and treat the patient properly loosening or removal of some of the patient’s clothes may be necessary. Respect the patient’s dignity and minimize heat loss. This will allow you to see any rashes (e.g. anaphylaxis) or perform procedures (e.g. defibrillation).

Common Emergencies

See also Appendix 1.1 for the Resuscitation Council guidelines (2012) on dealing with common emergencies.

Collapse (Table 1.3)

The cause of sudden loss of consciousness may be suggested by the medical history:

■ Collapse at the sight of a needle or during an injection is likely to be a simple faint.

■ Collapse of a diabetic at lunchtime, for example, is likely to be caused by hypoglycaemia.

Table 1.3

< ?comst?>

| Actions; reassure patient and accompanying people, and | |||||

| Emergency | Recognition | 1. Call for assistance | 2. Give oxygen 15 L/min | 3. Other main actions | 4. Alert emergency services |

| Anaphylaxis | Acute | Yes | Yes | Adrenaline (epinephrine) 500 mcg fo/> | |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses