CHAPTER 14

Maxillary Alveolar Split Horseshoe Osteotomy

Every noble work is at first impossible.

—Thomas Carlyle

Maxillary edentulous patients who present with adequate vertical alveolar height but a relatively narrow alveolus can be treated with a complete-arch U-shaped alveolar split osteotomy, termed the alveolar split horseshoe osteotomy. This procedure has utility in those patients who desire a fixed implant-supported prosthesis that provides restoration of gingivoalveolar contours, thereby avoiding a fixed-detachable prosthesis in favor of a more natural appearing, gingiva emerging, fixed denture. To allow this alternative, the alveolus must be returned to orthoalveolar form so that the arch relation is in axial alignment, the facial alveolar contours are normalized, gingival display is appropriate, and lip support is obtained.1–3 In this setting, the facial alveolar plane is reestablished, and the alveolar interplate dimension is restored.4,5 In other words, the narrow, atrophic alveolus is returned to its pre–dental extraction width in preparation for ideal implant placement.6

Although vertical loss of facial alveolar bone is the most frequently observed finding in patients with alveolar atrophy, many patients will retain the palatal plate for an extended period of time so that it can be split midcre-stally and expanded, allowing recovery of a facial bone plate and therefore the alveolar plane on the facial side.7,8 The horseshoe-shaped alveolar split moves the entire maxillary residual facial plate of bone away from the palatal plate. The maxilla advances up to 5 mm anteriorly even as it expands in a transverse dimension by 10 mm or more. With this simple procedure, the maxillary alveolar bone mass doubles or even triples in size.

A complete-arch alveolar split osteotomy graft is designed as an extended book flap, an extended island flap (i-flap), or a combination of the two (also see chapter 6). The bone flap usually involves an extended book flap posteriorly but an i-flap anteriorly, which generally segments at the canine locations when mobilized into a more anterior position. The posterior zone book flap maintains osseous attachment yet still provides sufficient transalveolar access for simultaneous sinus floor intrusion using blunt osteotomes.

Creation of intraosseous space for grafting is the hallmark of the osteoperiosteal flap9 (also see chapter 7). The alveolar split horseshoe osteotomy combined with sinus floor elevation is perhaps the largest of all the alveolar osteoperiosteal flaps, and for this reason, it is a very appropriate site for the use of iliac bone graft or recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2). The graft material is confined endosseously and, therefore, highly resistant to late-term resorption.10,11

Surgical Technique

Surgical Technique

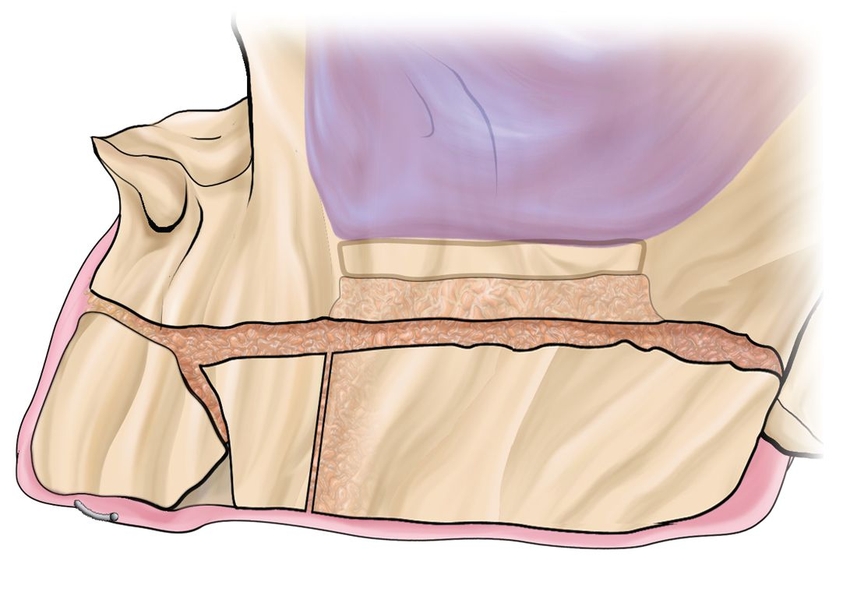

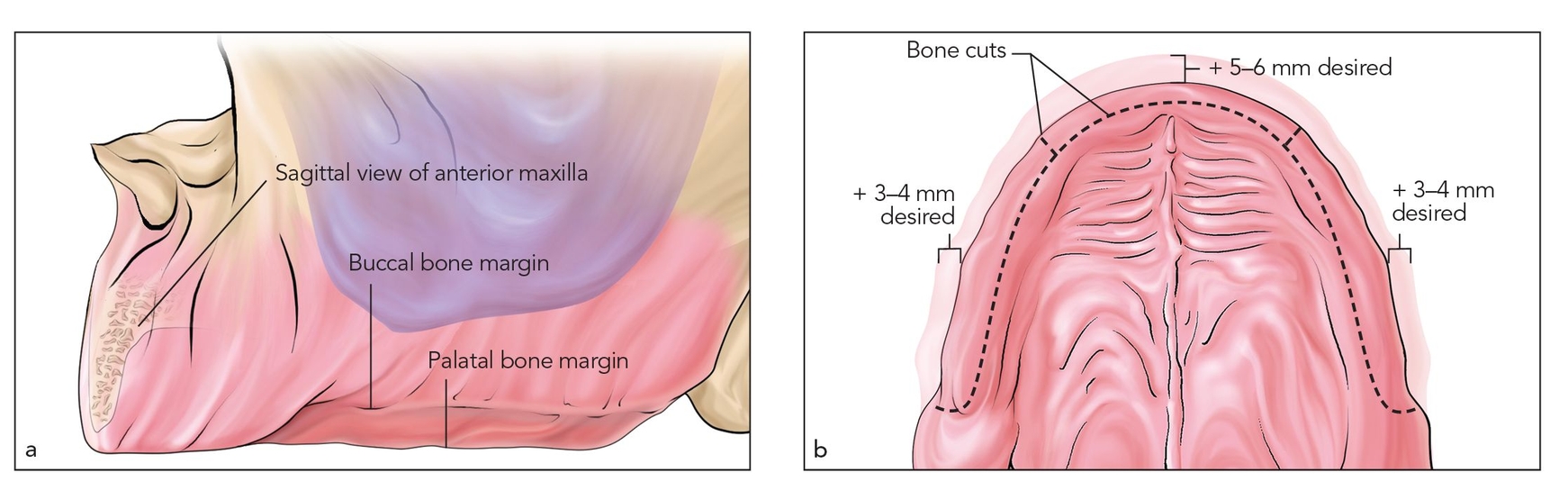

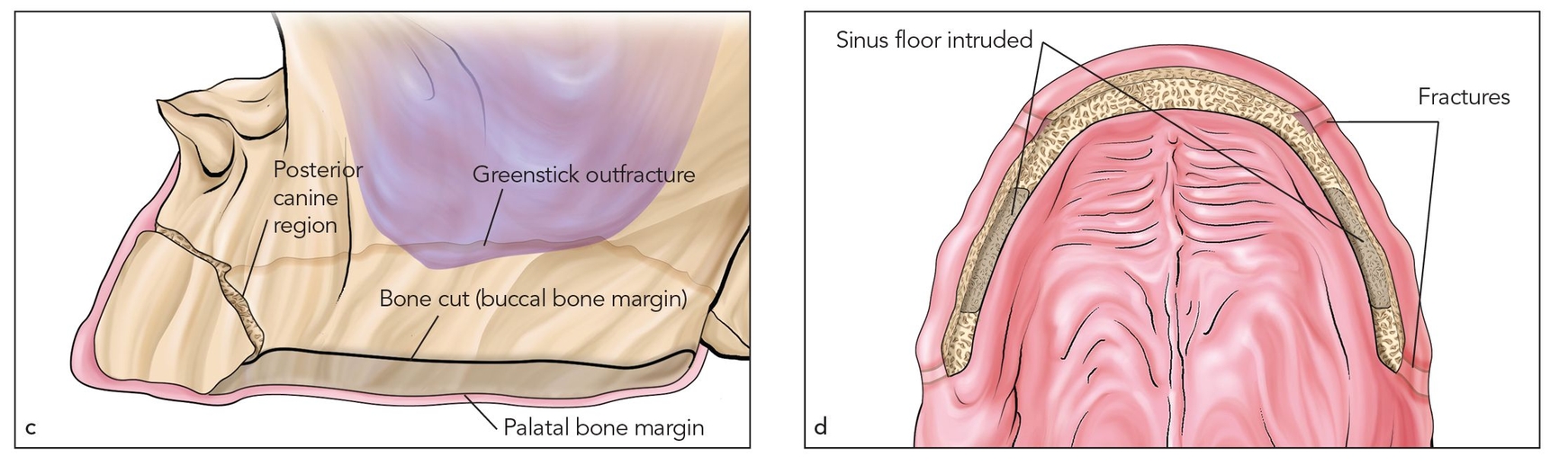

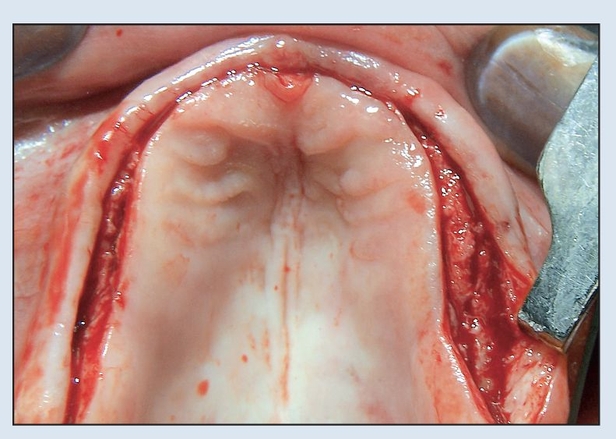

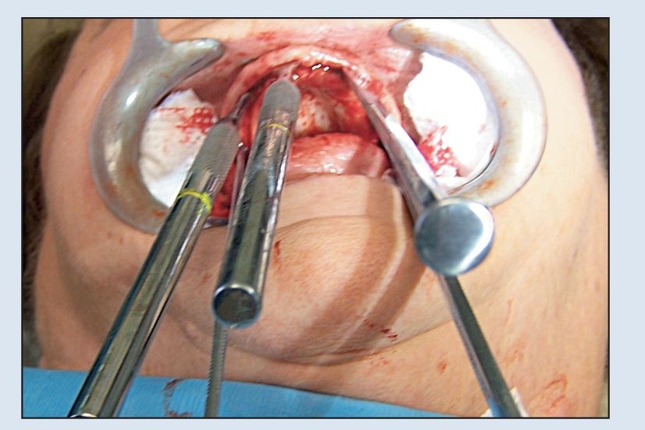

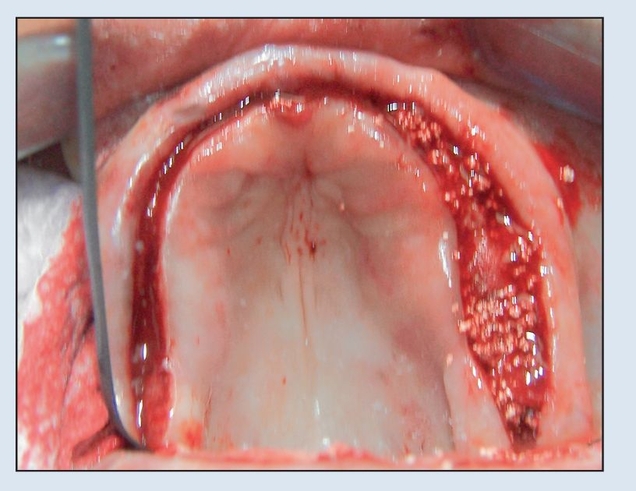

A crestal mucoperiosteal flap is created via an incision made along the palatal crestal margin around the maxillary arch; the incision is flared laterally at the tuberosities (Figs 14-1a and 14-1b). Once the crest is identified, piezoelectric surgery is used to split the alveolar process into two equal halves around the arch so that, when possible, a 2-mm-thick facial plate is created (Figs 14-1c and 14-1d). During the horseshoe alveolar split, segments frequently split spontaneously at the canine areas, creating three segments.

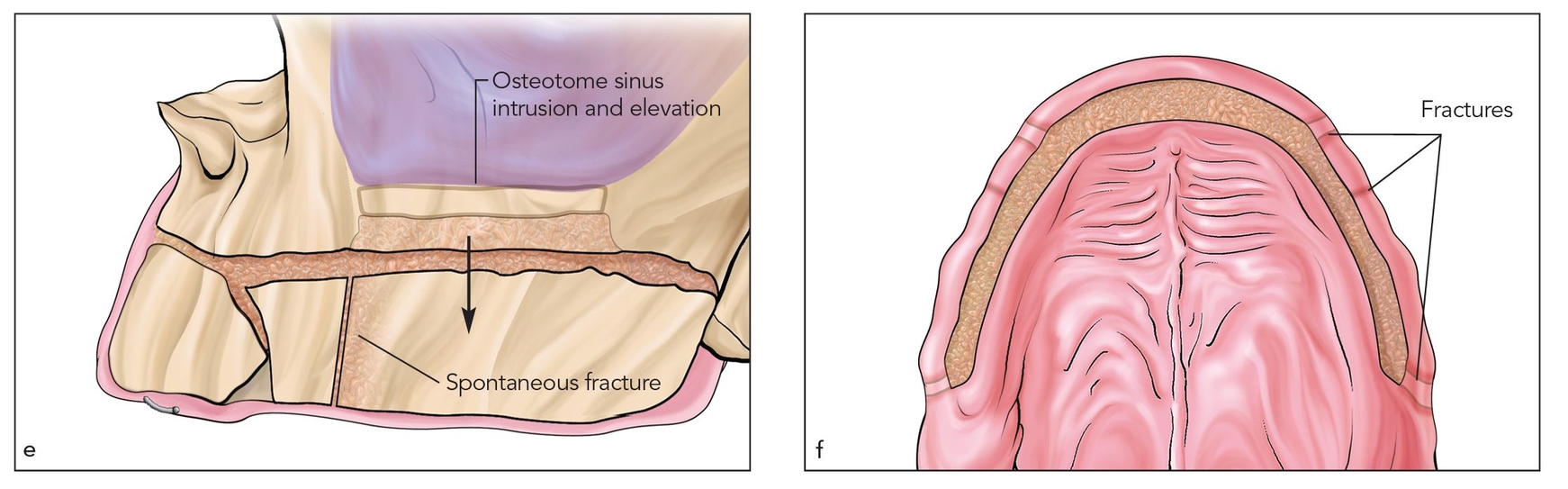

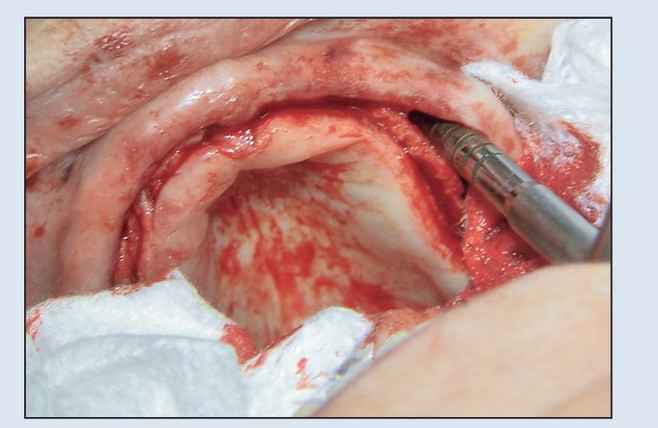

In the posterior region, the piezoelectric knife can extend to the sinus membrane, but it is better to remain a few millimeters short of the sinus floor because the sinus floor can then be intruded as an osteoperiosteal flap by using a blunt osteotome technique through the alveolar split access. The intrusion procedure is done bilaterally. In the posterior region, a book flap expansion of 3 or 4 mm is often sufficient, whereas in the anterior region, a 5- or 6-mm expansion is sometimes needed. In the anterior segment, as the U-shaped book flap is being developed, continuity with the posterior facial plate usually interrupts spontaneously, segmenting the anterior from the posterior. The anterior segment can be used as a book flap or, if desired, detached from the basal bone as an i-flap to allow free expansion of the segment more facially and vertically as is commonly needed. At all points, care should be taken not to detach periosteum from the osteoperiosteal segments.

When the splitting procedures are completed, rhBMP-2 or autogenous grafting material is interposed between the alveolar split plates and intruded into the sinus beneath the sinus floor bone flap (Figs 14-1e and 14-1f). The wound is closed primarily as much as possible or covered with collagen placed in any remaining gaps during wound closure.

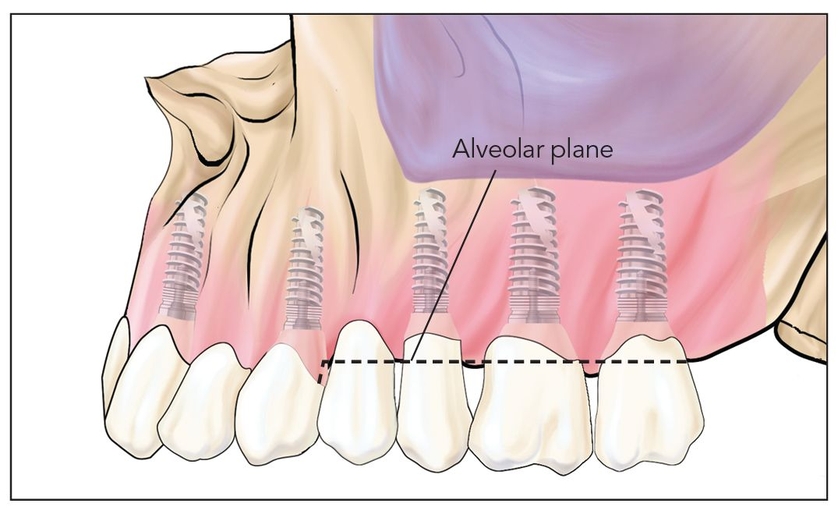

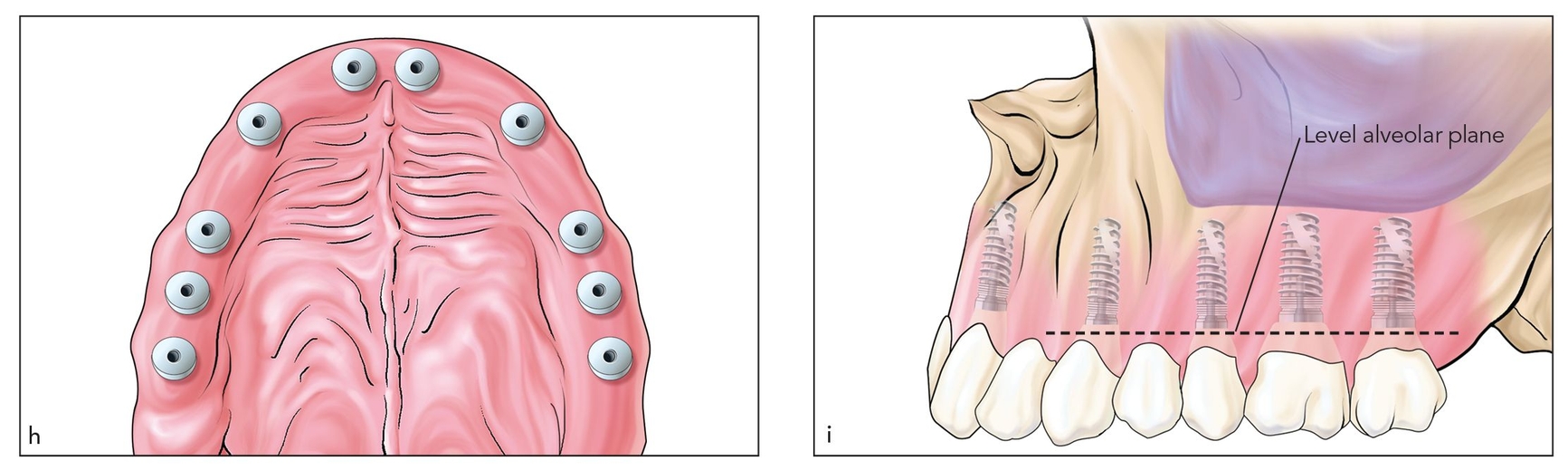

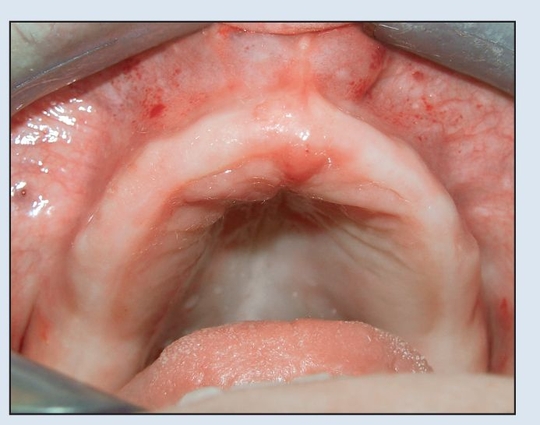

Implants are normally placed 6 months after the split, according to a guide stent, but can occasionally be placed simultaneously if sufficient apical bone is present for fixation. Final restoration proceeds 4 months later (Figs 14-1g to 14-1i).

Figs 14-1a and 14-1b The full maxillary arch alveolar split osteotomy allows for significant alveolar widening as well as access for transalveolar sinus grafting. Shown here is an atrophic maxilla with sufficient height anteriorly and at the posterior palatal plate but with a deficient buccal plate.

Figs 14-1c and 14-1d Alveolar split is done creating a greenstick outfracture near the level of the sinus floor. The segment is widened 5 mm using the book bone flap technique.

Figs 14-1e and 14-1f I-flaps are created to free the osseous attachment while still maintaining periosteal attachment. Spontaneous separation usually occurs in the canine areas to create three or more separate i-flaps.

Fig 14-1g Without an i-flap approach, the final alveolar split restoration would not have a level alveolar plane.

Figs 14-1h and 14-1i With i-flap leveling and width gain, implants are placed in the axial alignment, and the alveolar plane is restored.

Case Reports

Case Reports

Case 1: Severe alveolar width resorption with negligible marrow element

A 72-year-old woman, after long-term use of a maxillary complete denture, exhibited marked alveolar width resorption but only limited vertical resorption (Figs 14-2a and 14-2b). In a few areas, the facial and palatal plates appeared to have converged into a single plate of bone with negligible marrow element.

Osteotomy procedures

Following evaluation by computed tomography (CT), an alveolar split osteotomy was done through a minimally reflected palatal crestal incision that extended from tuberosity to tuberosity around the arch (Figs 14-2c and 14-2d). A piezoelectric knife and osteotomes were used to split the entire alveolar process from tuberosity to tuberosity (Fig 14-2e). The alveolus was widened in excess of 5 mm around the arch by means of a book flap outfracture technique in the posterior sextants and i-flap approach in the anterior sextant. In the posterior sextants, the book flap remained intact at the osseous level, where blunt osteotomes were used to elevate the entire sinus floor transalveolarly (Fig 14-2f).

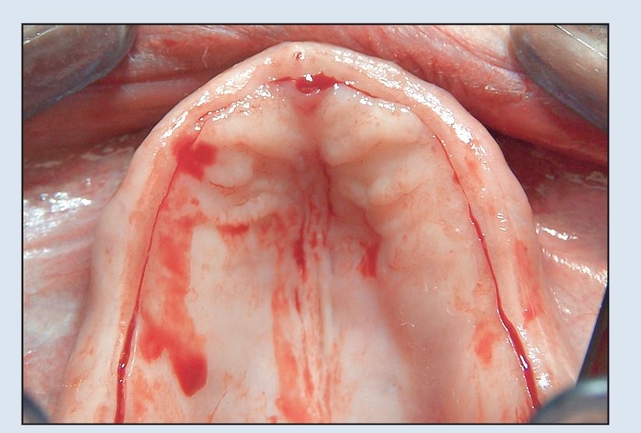

The procedure created an extremely large cavity that was packed with rhBMP-2–soaked collagen sponges in a particulated allograft matrix12 (Fig 14-2g). After the defect was overfilled with graft material, the alveolus could not be closed primarily. Collagen was placed over the wound margin, and oversuturing was done (Fig 14-2h), allowing the soft tissue to heal by secondary intention (Figs 14-2i and 14-2j). A denture was adjusted and relined and allowed to compress the wound. By 3 weeks postsurgery, soft tissue healing was completed.

Case 1: Severe alveolar width resorption with negligible marrow element

Fig 14-2a A 72-year-old woman presents with an edentulous maxilla but a complete mandibular dentition. She has worn a maxillary denture for more than 20 years.

Fig 14-2b Although at first glance the maxilla appears to have adequate width, the average alveolar width is 3 to 4 mm. Alveolar projection is deficient because of facial plate resorption.

Fig 14-2c A palatal crestal incision is made with minimal exposure of the alveolar crest.

Fig 14-2d Piezoelectric surgery is used to split the alveolar process to a depth of 10 mm. Less than 2 mm of bone is present buccally, so simultaneous implants are not planned.

Fig 14-2e Spade osteotomes are used to outfracture the entire maxilla in an extended U-shaped book flap.

Fig 14-2f In the posterior region, blunt osteotomes are used to intrude the sinus floor, creating an extended sinus floor osteoperiosteal flap.

Fig 14-2g Graft material, consisting of rhBMP-2 and allograft, is used to fill the very large interpositional and sinus floor defects.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses