Facial Growth and Development

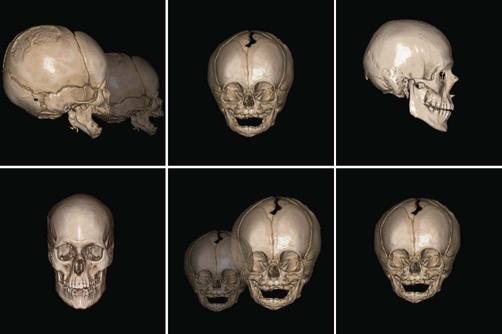

Growth of the face is a gradual and differential maturational process taking many years and requiring a succession of changes in regional proportions and relationships of various parts (Figure 14-1). An understanding of the mechanisms of growth and development of the face is pertinent to dentistry, in general, and is essential for the practice of dentistry. The objective of this chapter is to present an overall view of events occurring during facial growth and development.*

Facial Types

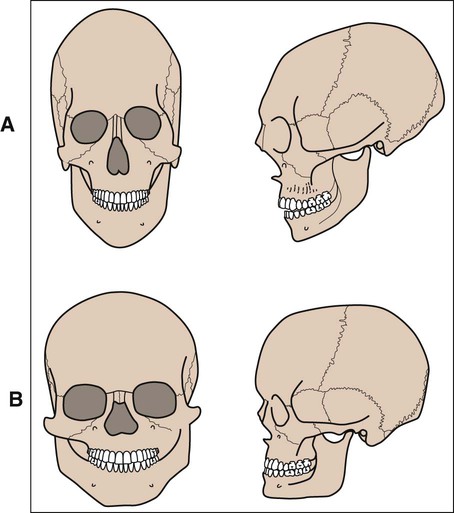

Although many intermediate types of head forms and facial patterns exist in any general population, these two skull configurations (Figure 14-2) tend to be associated with characteristic facial features. The narrow facial type tends to have a convex profile with a prognathic maxilla and a retrognathic mandible. The forehead slopes because the forward growth of the upper part of the face carries the outer table of the frontal bone with it. A larger frontal sinus than is characteristic of the broad facial type because of the greater separation of inner and outer bony tables of the forehead, whereas the inner table remains fixed to the dura of the frontal lobe of the cerebrum. The glabella and supraorbital rims are prominent, and the nasal bridge is high. There is a tendency toward an aquiline or Roman nose because the more prominent upper part of the nasal region induces a bending or curving of the nasal profile. Because the face is relatively narrow, the eyes appear close set, and the nose is correspondingly thin. The nose also is typically prominent and quite long, and its point has a tendency to tip downward. The lower lip and mandible are often set in a somewhat recessive position because the long dimension of the nasal chambers leads to a downward and backward rotational placement of the lower jaw (the dolichocephalic head form also has a more open cranial base flexure, which adds to the downward mandibular rotation). These factors contribute to a downward inclination of the occlusal plane and a marked curve of occlusion.

Facial Profiles

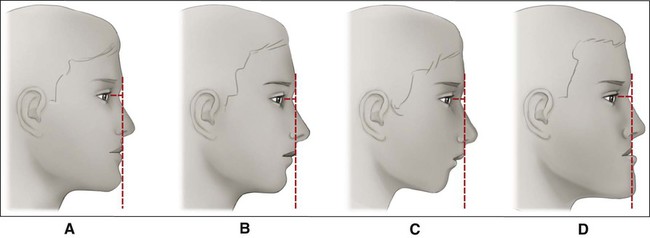

There are three basic types of facial profiles (Figure 14-3): (1) the straight-jawed, or orthognathic, type; (2) the retrognathic profile, which has a retruding chin and is the most common profile among white populations; and (3) the prognathic profile, which is characterized by a bold lower jaw and chin.

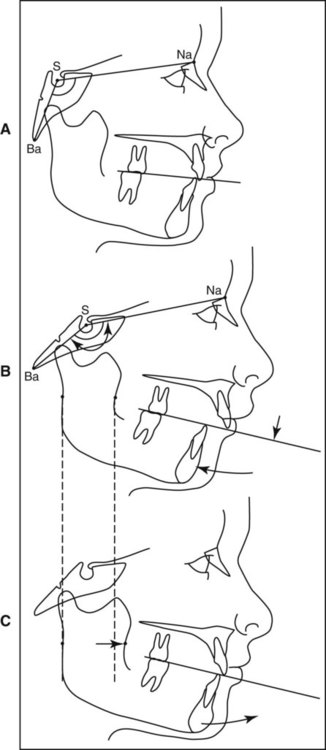

An important intrinsic developmental process of compensation functions to offset and reduce the anatomic effects of built-in tendencies toward malocclusions. A genetically determined retrognathic mandibular placement caused, for example, by some rotational factor in the cranial base can be compensated by the development of a broader mandibular ramus. Thus the whole mandible becomes longer and reduces the amount of retrognathism. Because latitude exists for compensatory adjustments, only a relatively slight degree of retrognathism, or some other anatomic imbalance, occurs in most persons (Figure 14-4). For narrow-faced individuals, 3 to 4 mm of mandibular retrognathism (a mild malocclusion with some crowding of the incisors) is typical. A perfect occlusion is hardly to be considered normal because relatively minor dental arch or facial skeleton irregularities are almost universal. Only when the compensatory process fails do severe malocclusions occur.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses