14 Dento-osseous Structures, Blood Vessels, and Nerves

The development of the dentitions has been discussed and a brief review of the development of the neurocranium and splanchnocranium has been presented in Chapter 2. Therefore, in this chapter the focus is on the dentoalveolar and dento-osseous structures of the permanent dentition. The forms of the roots of the teeth and their sizes and angulations govern the shape of the alveoli in the jawbones, and this in turn shapes the contour of the dento-osseous portions facially.

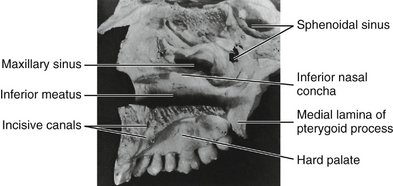

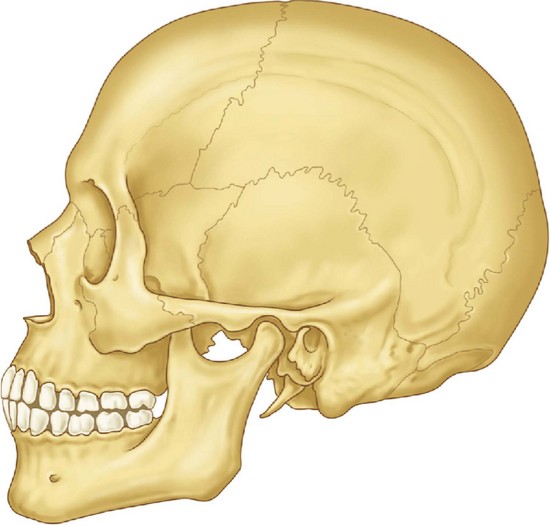

The osseous structures that support the teeth are the maxilla and the mandible. The maxilla, or upper jaw, consists of two bones: a right maxilla and a left maxilla sutured together at the median line. Both maxillae in turn are joined to other bones of the head (Figure 14-1). The mandible, or lower jaw, has no osseous union with the skull and is a movable (ginglymoarthrodial) joint.

Figure 14-1 Representation of an adult skull with permanent dentition. The maxilla consists of a body and four processes (malar, nasal, alveolar, and palatine) that articulate by synarthrosis with cranial and other facial bones, (e.g., frontal, nasal, ethmoid, malar bones). The mandible articulates with the temporal bone by the temporomandibular joint (see Figure 15-6).

The Maxillae

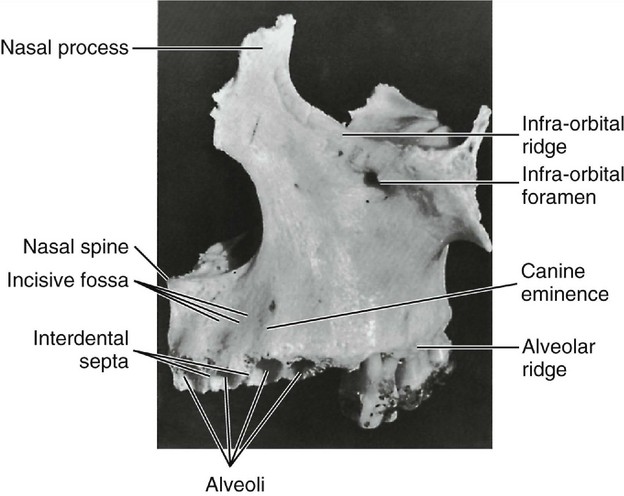

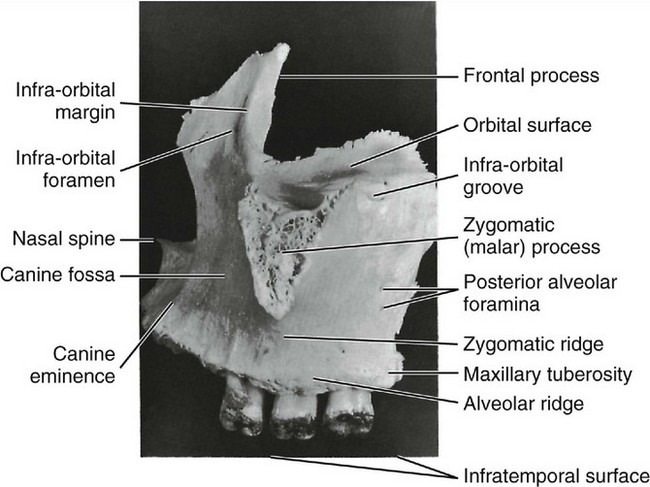

ANTERIOR SURFACE

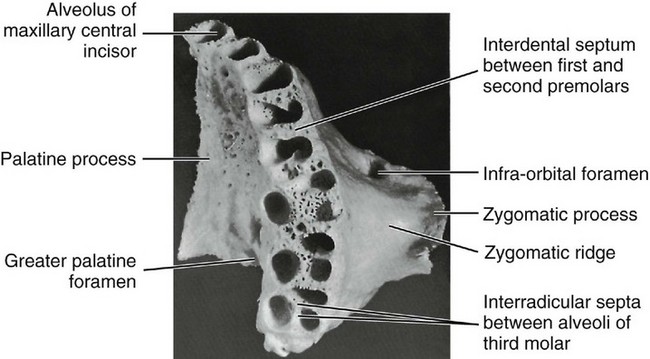

The anterior or facial surface (Figures 14-2 and 14-3) is separated above from the orbital aspect by the infraorbital ridge. Medially it is limited by the margin of the nasal notch, and posteriorly, it is separated from the posterior surface by the anterior border of the zygomatic process, which has a confluent ridge directly over the roots of the first molar. The ridge corresponding to the root of the canine tooth is usually the most pronounced and is called the canine eminence.

POSTERIOR SURFACE

The posterior or infratemporal surface (Figures 14-3 and 14-4) is bounded above by the posterior edge of the orbital surface. Inferiorly and anteriorly, it is separated from the anterior surface by the zygomatic process and the zygomatic ridge, which runs from the inferior border of the zygomatic process to the alveolus of the maxillary first molar. This surface is more or less convex and is pierced in a downward direction by two or more posterior alveolar foramina. These two canals are on a level with the lower border of the zygomatic process and are somewhat distal to the roots of the third molar.

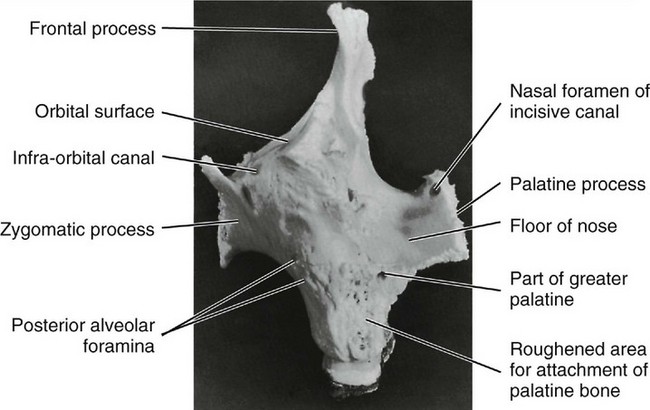

ORBITAL SURFACE

The thin medial edge of the orbital surface is notched anteriorly, forming the lacrimal groove. Behind this groove, it articulates for a short distance with the lacrimal bone, then for a greater length with a thin portion of the ethmoid bone, and terminates posteriorly in a surface that articulates with the orbital process of the palatal bone. Its lateral area is continuous with the base of the zygomatic process (see Figure 14-3).

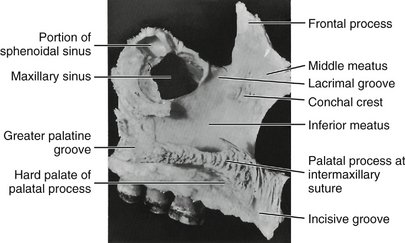

NASAL SURFACE

The nasal surface (Figures 14-5 and 14-6) is directed medially toward the nasal cavity. It is bordered below by the superior surface of the palatine process. Anteriorly, it is limited by the sharp edge of the nasal notch. Above and anteriorly, it is continuous with the medial surface of the frontal process. Behind this, it is deeply channeled by the lacrimal groove, which is converted into a canal by articulation with the lacrimal and inferior turbinate bones.

ZYGOMATIC PROCESS

The zygomatic process may be seen in the lateral views of the maxillary bone as a roughly triangular eminence whose apex is placed inferiorly directly over the first molar roots. The lateral border is rough and spongelike in appearance, where it has been disarticulated from the zygomatic or cheek bone (see Figures 14-1 and 14-3).

FRONTAL PROCESS

The frontal process (see Figures 14-2 through 14-5) arises from the upper and anterior body of the maxilla.

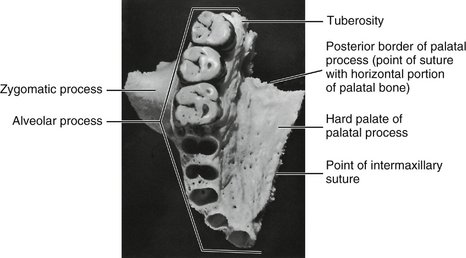

PALATINE PROCESS

The palatine process (Figures 14-2 through 14-8) is a horizontal ledge extending medially from the nasal surface of the maxilla. Its superior surface forms a major portion of the nasal floor. The inferior surfaces of the combined left and right palatine processes form the hard palate as far posteriorly as the second molar, where they articulate with the horizontal parts of the palatine bone (Figures 14-7 and 14-8) at the transverse palatine suture.

ALVEOLAR PROCESS

The alveolar process makes up the inferior portion of the maxilla; it is that portion of the bone which surrounds the roots of the maxillary teeth and which gives them their osseous support. The process extends from the base of the tuberosity posterior to the last molar to the median line anteriorly, where it articulates with the same process of the opposite maxilla (see Figures 14-7 and 14-8). It merges with the palatine process medially and with the zygomatic process laterally (see Figure 14-8).

The facial plate is thin, and the positions of the alveoli are well marked on it by visible ridges as far posteriorly as the distobuccal root of the first molar (see Figure 14-2). The margins of these alveoli are frail, and their edges are sharp and thin. The buccal plate over the second and third molars, including the alveolar margins, is thicker. Generally, the lingual plate of the alveolar process is heavier than the facial plate. In addition, the alveolar process is longer where it surrounds the anterior teeth, sometimes extending posteriorly to include the premolars. In short, it extends farther down in covering the lingual portion of the roots.

The bone is very thick lingually over the deeper portions of the alveoli of the anterior teeth and premolars. The merging of the alveolar process with the palatal process brings about this formation. The lingual plate is paper thin over the lingual alveolus of the first molar, however, and rather thin over the lingual alveoli of the second and third molars. This thin lingual plate over the molar roots is part of the formation of the greater palatine canal (see Figure 14-8).

ALVEOLI (TOOTH SOCKETS)

The alveolar cavities are formed by the facial and lingual plates of the alveolar process and by connecting septa of bone placed between the two plates. The form and depth of each alveolus are determined by the form and length of the root it supports (see Table 1-1).

The alveolus nearest the median line is that of the central incisor (Figure 14-9; see also Figure 14-8). The periphery is regular and round, and the interior of the alveolus is evenly tapered and triangular in cross section, with the apex toward the lingual.

The second alveolus in line is that of the lateral incisor. It is generally conical and egg-shaped, or ovoid, with the widest portion to the labial. It is narrower mesiodistally than labiolingually and is smaller on cross section, although it is often deeper than the central alveolus. Sometimes, it is curved at the upper extremity (Figure 14-10; see also Figure 14-8).

The canine alveolus is the third from the median line. It is much larger and deeper than those just described. The periphery is oval and regular in outline, with the labial width greater than the lingual. The socket extends distally. It is flattened mesially and somewhat concave distally. The bone is so frail at the canine eminence on the facial surface of the alveolus that the root of the canine is often exposed on the labial surface near the middle third (see Figure 14-2).

The first premolar alveolus (see Figures 14-8 and 14-10) is kidney-shaped in cross section, with the cavity partially divided by a spine of bone that fits into the mesial developmental groove of the root of this tooth. This spine divides the cavity into a buccal and a lingual portion. If the tooth root is bifurcated for part of its length, as is often the case, the terminal portion of the cavity is separated into buccal and lingual alveoli. The socket is flattened distally and much wider buccolingually than mesiodistally (see Table 1-1).

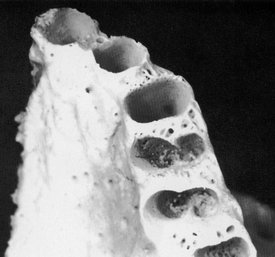

The first molar alveolus (Figures 14-8 and 14-11) is made up of three distinct alveoli widely separated. The lingual alveolus is the largest; it is round, regular, and deep. The cavity extends in the direction of the hard palate, having a lingual plate over it that is very thin. The lingual periphery of this alveolus is extremely sharp and frail. This condition may contribute to the tissue recession often seen at this site.

Figure 14-11 Alveoli of the molar area. Note the thinness of the buccal plates over the first molar roots compared with those of the second and third maxillary molars. The third molar alveoli are rarely separated as distinctly as in this specimen. Figures 14-9, 14-10, and 14-11 demonstrate a number of significant points concerning the maxillary alveoli. In Figure 14-9 the facial cortical plate of bone is thin over the anterior teeth and is considerably thicker over the posterior teeth, especially the molars. Cancellous bone seems to exist buccal to some of the posterior roots. In Figure 14-10 interradicular septa are thick but with numerous nutrient canals. In Figure 14-11 cancellous bone, furnishing numerous opportunities for blood supply, is evident in the apical portions of the alveoli. The anterior alveoli are lined laterally with a layer of smooth cortical bone. This lining is less prominent in the posterior alveoli.

The third molar alveolus is similar to that of the second molar, except that it is somewhat smaller in all dimensions. Figure 14-11 shows a third molar socket to accommodate a tooth with three well-defined roots, a rare occurrence. Usually, the two buccal (and often all three) roots will be fused. The interradicular septum changes accordingly. If the roots of the tooth are fused, a septal spine will appear in the alveolus at the points of fusion on the roots marked by deep developmental grooves.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses