Chapter 13

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) continue to be a major health problem worldwide and, in many instances, are on the increase. In the United States, some of the highest rates of infection occur in adolescents and young adults. More than 25 STDs have been identified and are listed in < ?xml:namespace prefix = “mbp” />Table 13-1. Current estimates predict that more than 65 million Americans are infected with one or more STDs, and 19 million new infections occur annually.1 The morbidity and mortality associated with STDs vary, with clinical consequences ranging from minor inconvenience or irritation to severe disability and death. The diagnosis of an STD also has psychosocial effects.

TABLE 13-1 Sexually Transmitted Diseases

| Disease | Pathogen |

|---|---|

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)55 |

| Amebiasis | Entamoeba histolytica |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Bacteroides spp., Mobiluncus spp. |

| Chancroid | Haemophilus ducreyi |

| Condyloma acuminatum (genital warts) | Human papillomavirus (HPV-6, HPV-11) |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | Cytomegalovirus |

| Enterobiasis | Enterobius vermicularis |

| Epididymitis, mucopurulent cervicitis, lymphogranuloma venereum, nongonococcal urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, Reiter’s syndrome | Chlamydia trachomatis |

| Epididymitis, gonorrhea, mucopurulent cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| Genital herpes | Herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1, HSV-2) |

| Giardiasis | Giardia lamblia |

| Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis) | Calymmatobacterium granulomatis |

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B virus (HBV) |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Poxvirus |

| Nongonococcal urethritis, nonspecific vaginitis | Trichomonas vaginalis |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Ureaplasma urealyticum |

| Pediculosis | Pediculus pubis |

| Salmonellosis | Salmonella spp. |

| Shigellosis | Shigella spp. |

| Streptococcal infection | Group B streptococci |

| Syphilis | Treponema pallidum |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Candida spp., Torulopsis spp. |

STDs have important implications for clinical practice in dentistry:

• STDs are transmitted by intimate interpersonal contact, which can result in oral manifestations. Dental health professionals need to be cognizant of these manifestations as a basis for referral of patients for proper medical treatment.

• Some STDs can be transmitted by direct contact with lesions, blood, or saliva, and because many affected persons may be asymptomatic, the dentist should approach all patients as though disease transmission were possible and must adhere to standard precautions.

• A single STD is accompanied by additional STDs in about 10% of cases, and STD-associated genital ulceration increases the risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1–3

• Pathogens responsible for STDs can exhibit antimicrobial resistance, thus proper treatment is essential.1,4

• Some STDs are incurable, but all are preventable.

• Patient interaction with dental health care workers can be an important component of STD control by providing opportunities for diagnosis, education, and information regarding access to treatment.

Although most STDs have the potential for oral infection and transmission, discussion in this chapter is limited to gonorrhea, syphilis, and select human herpesvirus and human papillomavirus infections. In addition to the medical consequences, patients should be aware that in certain cases, such as when transmission occurs through negligence or nondisclosure, it may be possible to file a lawsuit if someone gives you an STD.

Gonorrhea

Definition

Gonorrhea is an STD of worldwide distribution that is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. It produces symptoms in men that usually cause them to seek treatment soon enough to prevent serious sequelae, but maybe not soon enough to prevent transmission to others. Infections in women often do not produce recognizable symptoms until complications have emerged. Because gonococcal infections among women frequently are asymptomatic, an important component of gonorrhea control in the United States continues to be the screening of women who are at high risk for STDs. Of note, patients infected with N. gonorrhoeae often are coinfected with Chlamydia trachomatis.

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported infectious disease and STD in the United States, behind chlamydial infection. An estimated 700,000 new cases are reported each year in the United States, and about half of these are reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1,5 The reported incidence of gonorrhea in 2009 (i.e., 111 cases per 100,000 persons) was the lowest ever reported in the United States and was significantly lower than the incidence in the mid-1970s, when more than 1 million cases were reported.5,6

Humans are the only natural hosts for this disease, and its occurrence is worldwide. Gonorrhea is transmitted almost exclusively by sexual contact, whether genital–genital, oral–genital, or rectal–genital. The primary sites of infection are the genitalia, the anal canal, and the pharynx.

Gonorrhea can occur at any age, although it is seen most commonly in sexually active teenagers and young adults (8.5 per 1000 in the 15- to 29-year-old age group) and in the South. Rates of infection are similar in men and women, but differ by racial background. African Americans and Hispanics have 20.5 times higher rates of gonorrhea than whites.5 Risk factors other than age include young age at first sexual experience, multiple sexual partners, low level of education, low socioeconomic status, and living in an urban setting.1,5 At the current rate of infection, an average dental practice of 2000 adult patients can expect to provide care for 2 patients with gonorrhea.

Etiology

Gonorrhea is caused by N. gonorrhoeae, a gram-negative intracellular diplococcus. N. gonorrhoeae is an aerobic microbe that replicates easily in warm, moist areas and preferentially requires high humidity and specific temperature and pH for optimum growth. It is a fragile bacterium that is readily killed by drying, so it is not easily transmitted by fomites. It develops resistance to antibiotics rather easily, and many strains have become resistant to penicillin, tetracycline, and quinolones.

Pathophysiology and Complications

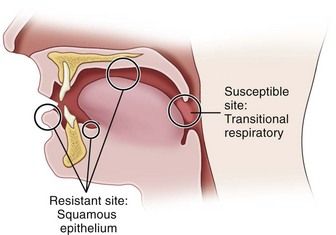

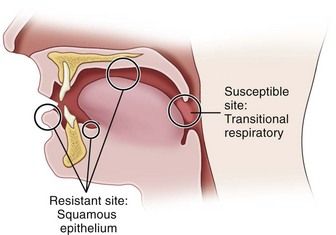

N. gonorrhoeae infects columnar epithelium (as found in the mucosal lining of the urethra and cervix) and transitional epithelium (as in the oropharynx and rectum), whereas stratified squamous epithelium (skin and mucosal lining of the oral cavity) generally is resistant to infection.7 This anatomic susceptibility explains the occurrence of rectal, pharyngeal, and tonsillar infections and the relative infrequency of oral infection, and the fact that there are no reported cases of gonorrhea occurring in the skin of the fingers. Figure 13-1 depicts the areas of relative epithelial susceptibility to N. gonorrhoeae infection in the oral cavity and oropharynx.

FIGURE 13-1 Areas of relative epithelial susceptibility to infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae within the oral cavity.

Infection in men usually begins in the anterior urethra. The bacteria invade epithelial tissues and are engulfed within polymorphonuclear leukocytes, leading to cytokine production and purulent discharge.7 The infection may remain localized or may extend to the posterior urethra, bladder, epididymis, prostate, or seminal vesicles. It spreads by means of lymphatics and blood vessels. Gonococcemia, although infrequent (occurring in 1% to 2% of cases), may occur and results in dissemination of the disease to distant body sites. Epididymitis is another complication of infection that can lead to infertility.

Infection in women occurs most commonly in the cervix and the urethra. Invasion of cervical epithelium can be associated with the production of a purulent exudate but more often leads to an ascending infection of the endometrium, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and pelvic peritoneum. The ascending infection is a common cause of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which affects about 1 million women each year in the United States.1 PID can be symptomatic or asymptomatic and may contribute to tubal scarring and infertility or ectopic pregnancy. Disseminated gonorrhea also can occur, with varying frequency. Vertical transmission accounts for a small percentage of cases of gonorrhea in the United States. If the infection goes untreated, it can cause blindness or joint infection in infants.

In both genders, gonorrhea of the rectum may occur after anal–genital intercourse or through direct anal contamination from genital lesions. Infection of the pharynx and oral cavity is predominantly seen in women and homosexual men after fellatio. It also occasionally is seen after cunnilingus.

Widespread dissemination is more likely in infected persons lacking select complement proteins. The gonococcemia can lead to variety of disorders, including migratory arthritis, skin and mucous membrane lesions, endocarditis, meningitis, PID, and pericarditis.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

In men, symptoms usually occur after an incubation period of 2 to 5 days, although they may take as long as 30 days to appear. The most common findings include a mucopurulent (white, yellow, or green) urethral discharge, burning pain on urination, urgency, and frequency. Tenderness and swelling of the meatus may occur.

In women, a significant percentage of cases may be asymptomatic or only minimally symptomatic. Symptomatic infection may demonstrate vaginal or urethral discharge, dysuria with frequency and urgency, and burning pain when urinating. Backache and abdominal pain also may be present.

Approximately 50% of women and 1% to 3% of men are asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic. This is unfortunate because patients may not seek medical care for their problem and as a result constitute a large reservoir of infection.

Gonococcal infection of the anal canal commonly is less intense than genital infection, but similar signs and symptoms, including a copious purulent discharge, soreness, and pain, may be noted.

Within the oral cavity, the pharynx is most commonly affected.8 Pharyngeal infection is reported to occur in 3% to 7% of heterosexual men, 10% to 20% of heterosexual women, and 10% to 25% of homosexual men.9 It usually is seen as an asymptomatic infection with diffuse, nonspecific inflammation or as a mild sore throat. The likelihood of transmission of pharyngeal gonorrhea to the genitalia seems much less than that of genital–genital transmission.10,11 Of significance, however, is the fact that N. gonorrhoeae has been cultured in expectorated saliva from two thirds of patients with oropharyngeal gonorrhea.10

Gonococcal stomatitis or oral gonorrhea is uncommon; case reports in the literature are limited.9,12–15 Acute temporomandibular joint arthritis caused by disseminated gonococcal infection from a genital site has been described.16

Laboratory Findings

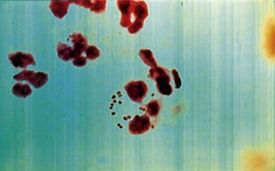

Laboratory diagnosis of a genital N. gonorrhoeae infection can be made based on the finding of gram-negative diplococci within polymorphonuclear leukocytes in a smear of urine or of purulent discharge in symptomatic mean (Figure 13-2). In women and asymptomatic men, nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) of urine is recommended because of its high sensitivity and specificity, and it can be used to simultaneously test for C. trachomatis.1,17 Culture is also available for diagnosis of N. gonorrhoeae from rectal and pharyngeal specimens. In suspected cases of oropharyngeal gonorrhea, because other species of Neisseria are normal inhabitants of the oral cavity, NAAT is more specific than a gram stain.

Medical Management

The CDC recommendations1 offer several choices for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infection of the cervix, urethra, and rectum. The single-dose regimens are: injectable ceftriaxone 250 mg (intramuscularly [IM]) in a single dose) or oral cefixime 400 mg in a single dose. Alternatively, a single-dose of injectable cephalosporin plus azithromycin 1 gram orally or doxycycline 100 mg a day for 7 days is recommended. Since patients infected with N. gonorrhoeae are often coinfected with Chlamydia trachomatis dosing regimens that include either azithromycin 1 g given orally in a single dose, or doxycycline 100 mg orally two times a day for 7 days is recommended. For patients who cannot take ceftriaxone, spectinomycin (2 g IM) or azithromycin 2 g are recommended alternatives. A very low (0.8%) treatment failure rate has been reported with ceftriaxone-doxycycline in the United States, and follow-up cultures are not considered essential unless symptoms persist. After antibiotic therapy is begun, infectiousness is diminished rapidly (within a matter of hours).11,17 Infections detected after treatment are generally the result of reinfection by a sexual partner—not treatment failure. Due to widely disseminated quinolone-resistant strains (QRNs) quinolones are no longer recommended for treatment of gonorrhea.

The clinician should be aware that gonococcal pharyngitis is more difficult to eradicate than infections at urogenital and anorectal sites.17 Few antimicrobial regimens can reliably cure such infections more than 90% of the time, and IM cefixime 250 mg plus azithromycin 1 g single oral dose or doxycycline 100 mg a day for 7 days is recommended.1 As with all STDs, all sex partners of patients who have N. gonorrhoeae infection should be assessed and treated.

Syphilis

Definition

Syphilis is an acute and chronic STD, caused by Treponema pallidum, that produces skin and mucous membrane lesions in the acute phase and bone, visceral, cardiovascular, and neurologic disease in the chronic phase. The variety of systemic manifestations associated with the later stages of syphilis resulted in its historical designation as the “great imitator” disease. As with gonorrhea, humans are the only known natural hosts for syphilis. The primary site of syphilitic infection is the genitalia, although primary lesions also occur extragenitally. Syphilis remains an important infection in contemporary medicine because of the morbidity it causes, and because it enhances the transmission of HIV.18

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

Syphilis is the fifth most frequently reported STD in the United States today, surpassed only by chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, salmonellosis, and AIDS. In 1990, the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis reached 50,223 cases.5 The number of cases of primary and secondary syphilis dropped to 6,000 in 2000. Since then, the rate has been steadily climbing. In 2009, almost 13,997 cases were reported, a rate of decline of 4.6 cases per 100,000 population.4,5,19 A disproportionately high number of cases continue to occur in the South and among Hispanic and non-Hispanic African American men and women. Syphilis occurs more commonly in persons aged 25 to 39 years. Its incidence in males is greater than in females, with a ratio of almost 6 : 1.19

Congenital syphilis occurs when the fetus is infected in utero by an infected mother. In 2008, a total of 431 cases of congenital syphilis were reported to the CDC. This represents a rate of 10.1 per 100,000 live births—higher than the 8.2 cases per 100,000 live births in 2005—but still a dramatic decline from the peak of 107.3 cases per 100,000 live births in 1991.19

Etiology

The etiologic agent of syphilis is Treponema pallidum, which is a slender, fragile anaerobic spirochete. It is transmitted predominantly sexually, including by oral–genital and rectal–genital contact with contaminated sores. However, transmission also can occur through nonsexual means such as kissing, blood transfusion, or accidental inoculation with a contaminated needle. Indirect transmission by fomites is possible but uncommon, because the organism survives for only a short time outside the body.1,20 T. pallidum is easily killed by heating, drying, disinfecting, and using soap and water. The organism is difficult to stain, except with use of certain silver impregnation methods. Demonstration is best done with darkfield microscopy on a fresh specimen.

Pathophysiology

Available evidence suggests that T. pallidum does not invade completely intact skin; however, it can invade intact mucosal epithelium and gain entry through minute abrasions or at the hair follicles. Within a few hours after invasion, bacterial spread to the lymphatics and the bloodstream occurs, resulting in early widespread dissemination of the disease. The early response to bacterial invasion consists of endarteritis and periarteritis.20 The risk of transmission is during the primary, secondary, and early latent stages of disease, but not in late syphilis.21 Overall, patients are most infectious during the first 2 years of the disease.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Manifestations and descriptions of syphilis are classically divided according to stages of the disease, with each stage having its own specific signs and symptoms related to disease duration and antigen-antibody responses. The stages are primary, secondary, latent, tertiary, and congenital. Of note, many infected persons do not develop symptoms for years, yet remain at risk for late complications if the infection is not treated.

Primary Syphilis

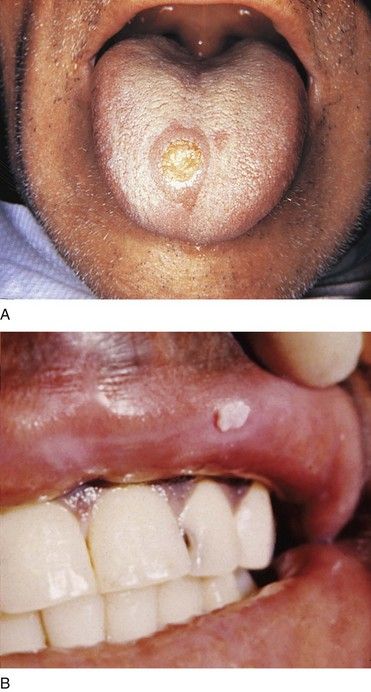

The classic manifestation of primary syphilis is the chancre, a solitary firm, round, granulomatous lesion that develops at the site of inoculation with the infectious organism. The chancre usually occurs within 2 to 3 weeks (range, 10 to 90 days) after exposure (Figure 13-3). Patients are infectious, however, before it appears. The lesion begins as a small papule and enlarges to form a surface erosion or ulceration that commonly is covered by a yellowish hemorrhagic crust and teems with T. pallidum. It typically is painless. Associated with the chancre are enlarged, painless, hard regional lymph nodes. The chancre usually subsides in 3 to 6 weeks without treatment, leaving variable scarring in the form of a healed papule.20,22 The genitalia, oral cavity (lips, tongue), fingers, nipples, and anus are common sites for chancres. Figure 13-4 shows examples of extragenital syphilitic chancres (lip and tongue). If adequate treatment is not provided, the infection progresses to secondary syphilis.

Secondary Syphilis

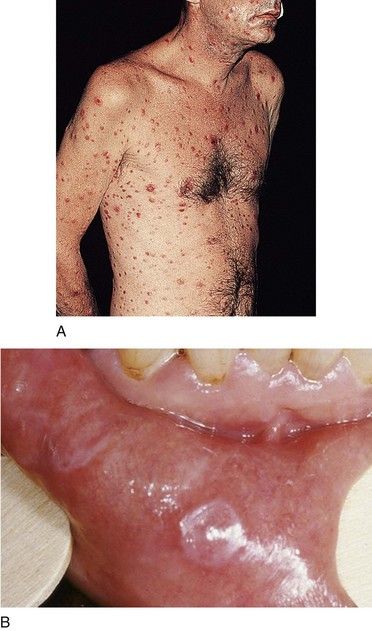

The manifestations of secondary syphilis appear 6 to 8 weeks after initial exposure. The chancre may or may not have completely resolved by this time. The symptoms and signs of secondary syphilis include fever, arthralgia and malaise, generalized lymphadenopathy, and patchy hair loss and develop in 80% of patients. Generalized eruptions of the skin and mucous membranes also occur (Figure 13-5, A) and include condyloma lata or wart-like growths on the genitalia. The papules of the rash are well demarcated and reddish brown and have a predilection for the palms and soles; they typically are not itchy. Oral manifestations of secondary syphilis include pharyngitis, papular lesions, erythematous or grayish-white erosions (mucous patches) (see Figure 13-5, B), irregular linear erosions, and, rarely, parotid gland enlargement. The lesions of skin and mucous membranes are highly infectious.20,22 Without treatment, clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis ultimately resolve; however, infection progresses to latent or the tertiary stages.

Latent Syphilis

Latent syphilis is defined as an untreated infection in which the patient displays seroreactivity but no clinical evidence of disease. This stage of the infection is divided into early latent syphilis (disease acquired within the preceding year) and late latent syphilis (disease present for longer than 1 year) or latent syphilis of unknown duration. During the first 4 years of latent syphilis, patients may exhibit mucocutaneous relapses and are considered infectious. After 4 years, relapses do not occur, and patients are considered noninfectious (except for blood transfusions and pregnant women).7,22 The latent stage may last for many years or, in fact, for the remainder of the person’s life. In some untreated patients, however, progression to tertiary syphilis occurs.

Tertiary (Late) Syphilis

The tertiary (late) stage occurs in roughly 1/3 of untreated persons, generally several years after disease onset.23 It is the destructive stage of the disease that involves mucocutaneous, osseous, and visceral structures). Signs and symptoms of this stage do not occur until years after the initial infection.

More than 80% of manifestations of tertiary syphilis are essentially vascular in nature and result from an obliterative endarteritis. Cardiovascular syphilis most commonly manifests as an aneurysm of the ascending aorta.

The benign tertiary stage of syphilis is classically characterized by the formation of gummas. These localized nodular, tender lesions may involve the skin, mucous membranes, bone, nervous tissue, and/or viscera. They are thought to be the end result of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. Pathologically, they consist of an inflammatory granulomatous lesion with a central zone of necrosis. Gummas are not infectious but can be destructive.

The oral lesions of tertiary syphilis consist of diffuse interstitial glossitis and the gumma. Interstitial glossitis should be considered a premalignant condition. The tongue may appear lobulated and fissured with atrophic papillae, resulting in a bald-appearing and wrinkled surface. Leukoplakia frequently is present. The oral gumma is a rare lesion that most commonly involves the tongue and palate. It appears as a firm tissue mass with central necrosis. Palatal gummas may perforate into the nasal cavity or maxillary sinus.

Neurosyphilis can occur during any stage of syphilis. It can produce a meningitis-like syndrome, Argyll Robertson pupils (which react to accommodation but not to light), altered tendon reflexes, general paresis, tabes dorsalis (degeneration of dorsal columns of the spinal cord and sensory nerve trunks), difficulty in coordinating muscle movements, cognitive dysfunction or insanity.

Congenital Syphilis

Syphilis or its sequelae occur in the newborn if the mother is infected while carrying the child. The disease is transmitted to the fetus in utero, usually after the 16th week, because before this time, the placenta prevents transmission of bacteria. The disease persists worldwide because a substantial number of women do not receive serologic testing for syphilis during pregnancy, or they may undergo testing too late in pregnancy to receive prenatal care.24 Physical manifestations vary according to the time of infection. The sequelae of early infection include osteochondritis, periostitis (frontal bossing of Parrot), rhinitis, rash, and ectodermal changes. Syphilis contracted during late pregnancy may involve bones, teeth (see “Oral Manifestations”), eyes, cranial nerves, viscera, skin, and mucous membranes. A classic triad of congenital syphilis known as Hutchinson’s triad includes interstitial keratitis of the cornea, eighth nerve deafness, and dental abnormalities, including Hutchinson’s incisors (Figure 13-6) and mulberry molars.

Laboratory Findings

T. pallidum has never been cultured successfully on any type of medium; therefore, the definitive diagnosis of syphilis is made from a positive darkfield microscopic examination or on the basis of direct immunofluorescent antibody tests on fresh lesion exudates. Darkfield examination yields consistently positive findings only during primary and early secondary stages. Definitive diagnosis of oral lesions by this method is difficult, because other species of Treponema are indigenous to the oral cavity.

Syphilis typically is diagnosed by a two-step process involving a nonspecific (screening) antibody test, followed by a treponeme-specific test. Screening antibody tests of blood also are known as serologic tests for syphilis (STS). These tests are of two basic types, indirect and direct, and are differentiated by the types of antibodies they measure.

Screening Serologic Tests for Syphilis: Nontreponemal Tests—VDRL and RPR

Standard screening tests for syphilis consist of the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) slide test, the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, and the automated reagin test (ART). These indirect, nontreponemal serologic tests are designed to detect the presence of an antibody-like substance called reagin that is produced when T. pallidum reacts with various body tissues. They are equally valid. A disadvantage of reaginic tests is the occasional biologic false-positive result that can occur.

Nontreponemal tests produce titers (reported quantitatively as serologic dilutions [e.g., 1 : 2, 1 : 4, 1 : 8]) that usually correlate with disease activity. Results are consistently positive and the highest titers are obtained between 3 and 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. In primary syphilis, nontreponemal tests usually revert to negative within 12 months after successful treatment. In secondary syphilis, up to 24 months may be required for the patient to become seronegative. Occasionally, a patient will remain seropositive for life, or will test positive in the presence of an associated infection or condition (false-positive). With tertiary syphilis, many patients remain seropositive for life.1

Confirmatory Serologic Tests for Syphilis: Treponemal Tests (FTA-ABS and MHA-TP)

Treponemal tests are designed to detect the specific antibody produced against treponemes that cause syphilis, yaws, and pinta.7,22 These tests are more specific than reaginic tests but less sensitive. Thus, they typically are performed after a positive VDRL or RPR. The fluorescent treponemal antibody (FTA) test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, and T. pallidum particle agglutination test (TP-PA) are examples. Treponemal antibody titers wane over time but remain positive in about 80% of patients, regardless of treatment. Thus, they should not be used to assess response to treatment.1 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for specific treponemal DNA sequences may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis when other studies are inconclusive.

Medical Management

Parenteral injection of long-acting benzathine penicillins (e.g., penicillin G, 2.4 million U IM in a single dose) remains the recommended treatment for primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis. Additional doses for 3 weeks are recommended for patients who have had syphilis for longer than a year (late latent). Alternative drugs for patients allergic to penicillin include oral doxycycline (100 mg orally two times a day for 2 weeks), tetracycline (500 mg orally four times a day for 2 weeks), or azithromycin.1 Testing for HIV serostatus and treatment of sexual partners also are recommended. After completing treatment, patients should be retested at 6 and 12 months to monitor for seroconversion status. A low failure rate has been reported in the treatment of syphilis. An important aspect to note in the management of syphilis is that, as with gonorrhea, infectiousness is reversed rapidly, probably within a matter of hours, on initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment.22

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile reaction that frequently is accompanied by chills, myalgias, hyperventilation, and headache that occur within 24 hours after initiation of therapy for syphilis. It occurs most often (i.e., in 50% patients) after treatment for early syphilis.

Congenital syphilis is best managed through implementation of preventive measures. This approach requires that all pregnant women be screened for syphilis by serologic testing at the first prenatal visit. If results are positive, the expectant mother should be treated with penicillin and retested at the 28th week and again at delivery. Infants born to seroreactive mothers should be assessed by means of clinical, radiographic, and laboratory tests of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for VDRL. If results prove the disease or suggest that syphilis is highly probable, then infants should be treated with intravenous penicillin G for at least 10 days. The treatment response for congenital and tertiary stages of syphilis is limited by the extent of damage already incurred.

Genital Herpes

Definition

Genital herpes is a life-long viral disease of the genitalia that is caused by one of two closely related types of herpes simplex virus (HSV)—HSV-1 and HSV-2. Most genital herpes infections are caused by HSV-2. The disease consists of acute and recurrent phases and is associated with high rates of subclinical infection and asymptomatic viral shedding. The prevalence of genital herpes has increased by 30% since the late 1970s.25

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

Genital herpes is an important STD worldwide. Its exact incidence in the United States is unknown because it is not a reportable disease, and most persons have not been diagnosed because their disease is mild or asymptomatic. An estimated 50 million people, or more than 25% of persons 12 years of age and older, in the United States are infected.1,25 An estimated 1.6 million new cases of HSV-2 occur annually in the United States.26,27 The prevalence in developing countries is between 40% and 60%.27 About 70% to 95% of first-episode cases of genital herpes are caused by HSV-2, whereas up to 30% in some series are caused by HSV-1.1 Prevalence rates in women (25%) and in African Americans (46%) are reportedly higher than those in men (20%) and in whites (18%).25 Most persons infected with HSV-2 have not been diagnosed with genital herpes thus enhancing its transmission.

Etiology

HSV belongs to a family of eight human herpesviruses that includes cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), human herpesvirus type 6 (HHV-6), human herpesvirus type 7 (HHV-7), and Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (HHV-8). HSV-1 is the causative agent of most herpetic infections that occur above the waist, especially on the mucosa of the mouth (herpetic gingivostomatitis, herpes labialis), nose, eyes, brain, and skin. Infection with HSV-1 is extremely common; most adults demonstrate antibodies to this virus. It is thought that many primary infections with HSV-1 are subclinical and thus are never known to the infected person. Transmission usually occurs through close contact, such as touching or kissing, and transfer of infective saliva. HSV-1 also is transmitted by sexual contact. Airborne droplet infection has not been well demonstrated, although it is possible.28 Autoinoculation from contact with face, fingers, eyes, and genitalia is a persistent clinical problem.

HSV-2 is the causative agent of most herpes infections that occur below the waist, such as in or around the genitalia (genital herpes). HSV-2 is transmitted predominantly by sexual contact but also may be passed nonsexually. Its primary mode of transmission is through an asymptomatic viral shedder. HSV-2 can be transmitted to a newborn from an infected mother.

Although the primary site of occurrence of HSV-1 is above the waist and of HSV-2 below the waist, each infection may occur at either site and in fact can be inoculated from one site to the other (Figure 13-7). Furthermore, the two types cannot be differentiated on basis of skin lesions and other clinical manifestations.

Pathophysiology and Complications

The pathologic processes of herpesvirus infections HSV-1 and HSV-2 are essentially identical; thus, the lesions of skin and mucous membranes are identical. Infection arises from intimate contact with a lesion or infective fluid (e.g., saliva). Epithelial cells are invaded, and viral replication occurs. Characteristic cellular changes include ballooning degeneration, intranuclear inclusion bodies, and the formation of multinucleated giant cells. With cellular destruction come inflammation and increasing edema, which result in formation of a papule that progresses to a fluid-filled vesicle. These vesicles rupture, leaving an ulcerated or crusted surface.

Lymphadenopathy and viremia are prominent features. In normal persons, the primary infection is contained by usual host defenses and runs its course within 10 to 20 days. However, spread to other epidermal sites (e.g., herpetic whitlow [infection of the fingers], keratoconjunctivitis [eyes]) and in neonates during childbirth has been documented. In rare cases, infants and immunosuppressed persons can develop systemic (meningitis) and widespread infection that may result in significant morbidity and death.

During the epithelial infection, progeny enter the ends of local peripheral neurons and migrate up the axon to the regional ganglion (HSV-1 primarily in the trigeminal, and HSV-2 primarily in the sacral), where they reside for the life of the host. After stimulation such as trauma, sunlight, menses, or intercourse, the virus can reactivate, migrate down the axon, and produce recurrent infection. Of the two HSV serotypes that can infect the sacral ganglia, HSV-2 is more efficient in reactivating and producing recurrent genital lesions, whereas HSV-1 may pose a greater risk for neonatal herpes.29 Also, immune suppression increases the risk for more frequent and severe recurrences.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Most (about 60%) new cases of HSV-2 infection are asymptomatic27; newly acquired cases are asymptomatic more frequently in men than in women. After an incubation period of 2 to 7 days, lesions (i.e., papules, vesicles, ulcers, crusts, and fissures) of primary genital herpes may appear. In women, both internal and external genitalia may be involved, as well as the perineal region and the skin of the thighs and buttocks. In men, the external genitalia is typically involved, as may the skin of the inguinal area. Lesions in moist areas tend to ulcerate early, are painful, and may be associated with dysuria. Lesions on exposed dry areas tend to remain pustular or vesicular and then crust over. Painful regional lymphadenopathy accompanies the primary infection, along with headache, malaise, myalgia, and fever. Clinical manifestations subside in about 2 weeks, and healing occurs in 3 to 5 weeks.

Outbreaks of recurrent genital herpes typically occur 2 to 6 times per year and generally are less severe and more localized than the primary infection. Recurrences frequently are precipitated by menstruation, intercourse, or immunosuppression. A prodrome of localized itching, tingling, paresthesia, pain, and burning may be noted and is variably followed by a vesicular eruption (Figure 13-8). Healing occurs in 10 to 14 days. Constitutional symptoms generally are absent. Between recurrences, infected persons shed virus intermittently and asymptomatically from the genital tract.

FIGURE 13-8 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection of the foreskin.

(From Habif TP, et al: Skin disease: diagnosis and treatment, ed 3, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

HSV-1 and HSV-2 lesions are highly infectious, promoting transmission to other people, or to other sites on the body. Orogenital contact may result in spread from the source to the oral cavity or genitals of the sexual partner. The infectious period of herpetic lesions is considered to extend until the crusting stage. Therefore, all herpetic lesions (i.e., papular, vesicular, pustular, and ulcerative) before completion of crusting should be assumed to be infectious.

Laboratory Findings

Cytologic examination of a smear (Tzanck preparation) taken from the base of a herpetic lesion reveals typical features, including ballooning degeneration of cells, intranuclear inclusion bodies, and multinucleated (fused) giant cells. However, cytologic evaluation is nonspecific and less sensitive than viral culture. Diagnosis is best established by swabbing an infected secretion or ulcer and isolating the virus by cell culture or amplifying its sequences by PCR. Cultured virus is identified by staining the infected cells for HSV antigen with the use of immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase. PCR is particularly helpful when neurologic symptoms develop and cerebrospinal fluid is sampled. Serologic detection of antibodies to HSV-1 glycoprotein G1 or HSV-2 glycoprotein G2 aids in diagnosis and management (e.g., counseling the patient about the potential for recurrences and transmission).1

Medical Management

Management of patients with a first clinical episode of genital herpes includes antiviral therapy and counseling regarding the natural history of genital herpes, sexual and perinatal transmission, and ways to reduce transmission. Current CDC recommendations1 call for the use of acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), or valacyclovir (Valtrex). All three are nucleoside analogue drugs that act as DNA chain terminators during virus replication in infected cells. Some of these agents are available in oral, topical, and intravenous formulations. Topical acyclovir therapy is substantially less effective than systemic drug administration, and its use is not recommended for genital herpes. Systemic antiviral drug therapy can shorten the duration, frequency, and symptoms of outbreaks and can reduce the frequency of asymptomatic shedding and the risk of transmission.30 Antiviral agents do not eliminate the virus from the latent state, however, nor do they affect subsequent risk, frequency, or severity of recurrence after drug use is discontinued. Antiviral drugs are most effective when given for prevention at least 1 day within appearance of symptoms, whether for primary or recurrent disease. Current treatment recommendations are addressed in Box 13-1.1 These protocols also may be used for oral infection. Intravenous antiviral agents (cidofovir [Vistide] and foscarnet [Foscavir]) are reserved for severe or complicated infections and may be required for immunosuppressed patients.

Box 13-1 Oral Regimens Recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the Treatment of Genital Herpes*

Primary Episode*

Recurrent Infection

• Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times a day for 5 days, or

• Acyclovir 200 mg orally five times a day for 5 days, or

• Acyclovir 800 mg orally twice a day for 2-5 days, or

• Famciclovir 125 mg orally twice a day for 5 days, or

• Famciclovir 500 mg once, then 250 mg twice daily for 2 days

• Famciclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 1 day

Daily Suppressive Therapy

• Acyclovir 400 mg twice daily, or

• Famciclovir 250 mg twice a day, or

• Valacyclovir 500 mg once a day, or

• Valacyclovir 1† g once a day

* NOTE: Treatment may be extended if healing is incomplete after 10 days of therapy. Higher dosages of acyclovir (e.g., 400 mg orally five times a day) were used in treatment studies of first-episode herpes proctitis and first-episode oral infection. However, comparative studies with respect to genital herpes have not been performed. Valacyclovir and famciclovir probably also are effective for acute herpes simplex virus proctitis or oral infection, but clinical experience is lacking.20

†Higher doses may be required for patients who have more than 10 recurrences per year.

Daily suppressive antiviral therapy can be implemented for patients with frequent recurrences (more than five recurrences per year). Suppressive therapy reduces the frequency of recurrence by 70% to 80% among persons who experience six or more recurrences per year and reduces asymptomatic viral shedding between outbreaks.1 Suppressive therapy has not been associated with emergence of clinically significant acyclovir resistance among immunocompetent patients. Because the frequency of recurrence tends to diminish over time in many patients, current recommendations include discussing periodically the possibility of discontinuing suppressive therapy to reassess the need for continued therapy.

Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir have been assigned pregnancy category C, B, and B, respectively, by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Accordingly, famciclovir and valacyclovir are considered relatively safe to administer to pregnant women.31

Infectious Mononucleosis

Definition

Although not classically defined as an STD, infectious mononucleosis is discussed in this chapter because transmission occurs through intimate personal contact. Infectious mononucleosis is an infection that is caused, in at least 90% of cases, by EBV, a lymphotropic herpesvirus. Other viruses also may produce features of acute infectious mononucleosis. Infectious mononucleosis produces the classic clinical triad of fever, pharyngitis, and bilateral symmetrical cervical lymphadenopathy. Transmission of the virus occurs primarily by way of the oropharyngeal route during close personal contact (i.e., intimate kissing). Children, adolescents, and young adults are affected most commonly. About 40% of asymptomatic herpesvirus-seropositive adults carry EBV in their saliva on any given day.32

Epidemiology

Incidence, Prevalence, and Etiology

More than 90% of adults worldwide have been infected with EBV. In the United States, about 50% of 5-year-old children and 70% of college freshmen have evidence of previous EBV infection.33,34 The peak age of acquisition in the United States is reportedly 15 to 19 years.35 The annual incidence in this adolescent age group is 3.4 to 6.7 cases per 1000 persons. Incidence has been reported as 30 times higher in whites than in blacks in the United States.33 No gender predilection has been noted. Having numerous sexual partners increases the risk for acquisition of EBV.

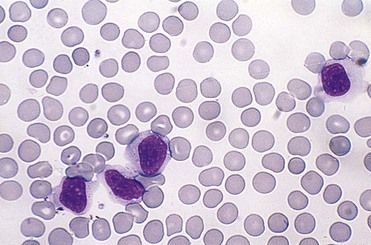

Pathophysiology

EBV is a lymphotropic herpesvirus that is transmitted primarily through close personal contact (i.e., intimate kissing) and exposure to infected saliva and oropharyngeal secretions. Infrequently, it is transmitted through shared infected drinks, eating utensils, or infected blood products. Incubation time is 30 to 50 days. A prodromal period of 3 to 5 days precedes the clinical phase, which lasts 7 to 20 days. During the prodromal phase, the virus infects oropharyngeal epithelial cells and spreads to B lymphocytes in the tonsillar crypts. Infected B lymphocytes circulate through the reticuloendothelial system, triggering a marked lymphocytic response. In infectious mononucleosis, large, reactive lymphocytes expand from 1% to 2% to 10% to 40% of the circulating white blood cells. These expanded T lymphocytes are reactive to the EBV-infected B lymphocytes (Figure 13-9).34 The combination of reactive lymphocytes, the cytokines they produce, and the B cell–produced (heterophile) antibodies directed against EBV antigens contributes to the clinical manifestation of the acute infection. Hepatosplenomegaly develops in about 40% to 50% of patients, self-limiting hepatitis develops in about 10%, splenic rupture occurs in 0.1% to 0.2% of all cases, and death is a rare outcome.34,36 After the acute infection, the EBV remains latent in B lymphocytes for the life of the host and is shed in the saliva. EBV is an effective transforming agent and is associated with the development of lymphomas and nasopharyngeal.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Infectious mononucleosis usually is asymptomatic when found in children; however, about 50% of infected young adults develop symptoms. Fever, sore throat, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, malaise, and fatigue are the predominant features. About a third of patients demonstrate palatal petechiae during the first week of the illness, and about 30% of patients develop an exudative pharyngitis.34,37,38 Generalized skin rash and petechiae of the lips are seen in about 10% of cases, and in sexually active persons genital ulcers may be present. The liver and spleen can enlarge, and become tender and inflamed. Symptoms tend to dissipate within 3 weeks of onset, and the majority recovers without apparent sequelae.

Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis is made on the basis of signs and symptoms and a laboratory profile characterized by marked lymphocytosis (e.g., 50% lymphocytes [primarily T lymphocytes]) with at least 10% atypical lymphocytes on a peripheral blood smear (see Figure 13-9) and a positive heterophile antibody test. Heterophile antibodies are immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies that bind (agglutinate) to antigens different from the antigen that induced them, such as erythrocytes from nonhuman (sheep, horses) species.42 This process forms the basis for the Monospot (Meridian Bioscience, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) rapid latex agglutination test. Symptomatic patients in whom a heterophile antibody test is negative should be retested in 7 to 10 days, because this test can be insensitive during the first week. If the second test is negative, tests for viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and VCA IgM antibody and EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) should be performed.38 These tests are more specific but costly. If test results are positive, the patient has heterophile-negative infectious mononucleosis. A few patients with the classic disease description may be heterophile antibody-negative and EBV IgM-negative. In these patients, tests for cytomegalovirus (CMV), Toxoplasma gondii, HHV-6, HIV, and adenovirus should be performed.33,38 Once EBV-associated mononucleosis has been diagnosed, EBV copy numbers in the blood can be used to monitor the severity and progression of the infection.39

Medical Management

Although a number of antiviral drugs can inhibit EBV replication in culture, no drug is yet licensed for clinical treatment of EBV infection. The lack of effective antivirals results from the fact that mononucleosis is largely due to the immune response. However, a recent study of 20 young adults with infectious mononucleosis, showed that valacyclovir can decrease the level of EBV oropharyngeal shedding and reduce the number and severity of symptoms.40

Nevertheless until larger studies are performed, treatment of patients with infectious mononucleosis remains symptomatic and supportive with bed rest, fluids, acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents for pain control, and gargling and irrigation with saline solution or lidocaine to relieve throat symptoms. Vigorous activity is to be avoided for at least 3 weeks to reduce the risk of rupture of an enlarged spleen. In some patients with severe toxic exudative pharyngotonsillitis, pharyngeal edema and upper airway obstruction, or seizures, a short course of prednisone may be given. About 20% of patients with symptomatic infectious mononucleosis have concurrent beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis and should be treated with penicillin V, if they are not allergic to penicillin. Ampicillin should be avoided because at least 90% of patients develop a hypersensitivity skin rash when treated with this drug.1,38 Most persons feel better and return to normal activities within a month.

Human Papillomavirus Infection

Definition

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small, double-stranded, nonenveloped DNA viruses that infect and replicate in epithelial cells. More than 100 genotypes of HPV have been identified, and more than 40 types are known to be sexually transmitted and to affect anogenital epithelium.1 Each HPV subtype exhibits preferential anatomic sites of infection and a propensity for altering epithelial growth and replication. The spectrum of disease that is induced is dependent on the type of HPV infection, location, and immune response. Subtypes of HPV have been classified as high-risk, intermediate-risk, or low-risk types. Low-risk HPVs (HPV-6, -11) produce benign proliferative lesions of mucocutaneous structures. Intermediate-risk HPVs are oncogenic. High-risk HPV types (HPV-16, -18) are strongly associated with dysplasia and carcinoma of the uterine and anal tract and other mucosal sites.41,42 Table 13-2 lists HPV-associated lesions.

TABLE 13-2 Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Oral Mucosa Lesions

| Lesion | Most Common HPV Types |

|---|---|

| Condyloma acuminatum | 6, 11 |

| Epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, squamous cell carcinoma | 2, 16, 18 |

| Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease) | 13, 32 |

| Lichen planus | 11, 16 |

| Oral bowenoid papulosis | 6, 11, 16 |

| Squamous papilloma | 6, 11 |

| Verruca plana | 3, 10 |

| Verruca vulgaris | 2, 4, 6, 11, 16 |

| Verrucous carcinoma | 2, 6, 11, 16, 18 |

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

HPV infections are one of the three most common STDs in the United States. An estimated 20 million people in the United States have genital HPV infection,1 which can be transmitted through sexual contact.45 Although the exact incidence of HPV infection remains unknown, because HPV-induced diseases is not a reportable STD and most cases are asymptomatic or subclinical, it is estimated that more than 6 million new infections occur every year in the United States,1 and up to 40% of sexually active persons are infected with the virus.43,44 The infection is more common among African American women than white women. The highest rates of infection are in persons between 19 and 26 years of age.44 Approximately 1% of sexually active adults in the United States have visible genital warts.45 The lifetime number of sexual partners is the most important risk factor that has been identified for the development of genital warts.46,47

Etiology

Genital HPV can be transmitted by direct contact during sexual intercourse or passage of a fetus through an infected birth canal, or by autoinoculation. Genital lesions usually appear after an incubation period of 3 weeks to 8 months. The most common manifestation of HPV replication is the venereal wart, or condyloma acuminatum. HPV types 6 and 11 are the subtypes most frequently associated with condyloma acuminatum.48 Less commonly, HPV type 2 has been identified in condylomata.

Pathophysiology

HPV is transmitted through mucosa, skin-to-skin, or sexual contact. The virus replicates in the nuclei of epithelial cells and increases the turnover of infected cells, or it remains episomally in a latent state. Benign types such as HPV-6 and -11 have a strong tendency to induce epithelial hyperplasia and wart-like growths. High-risk HPV types (HPV-16 and -18) have a propensity to induce dysplasia and malignant transformation. HPV types 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 54, 56, and 58 are considered intermediate for inducing carcinoma. Persistent oncogenic HPV infection is the strongest risk factor for the development of precancer and cancer, with HPV DNA detected in 99.7% of cervical cancers. Smoking is also a contributory cofactor.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

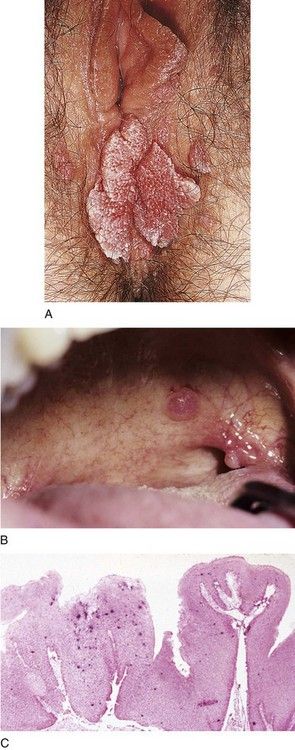

Most persons infected with HPV are asymptomatic, and the infection clears on its own. Visible genital warts caused by HPV-6 or -11 typically are diagnosed as condyloma acuminatum. These growths are seen in sexually active persons and arise in warm, moist, intertriginous areas such as the anogenital skin and mouth, where friction and microabrasion allow entrance of the pathogen. Condylomata appear as small, soft, exophytic papillomatous growths (Figure 13-10, A). The irregular-appearing surface has been described to resemble a head of cauliflower; the base is sessile. The borders are raised and rounded. The color varies, ranging from pink to dusky gray. Lesions often are multiple and recurrent and can coalesce to form large, pebbly warts. Most condylomata are asymptomatic; however, patients may report itching, irritation, pain, or bleeding as a result of manipulation or trauma. During pregnancy, condylomata may enlarge as the result of increased vascularity. Condylomata can occur on the vagina, anus, mouth (see Figure 13-10, B), pharynx, or larynx and may appear weeks or months after the onset of infection.

FIGURE 13-10 Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infections.

A, Large, cauliflower-like wart of the vagina. B, Dome-shaped HPV-induced lesions of the soft palate and retromolar trigone. C, In situ hybridization showing HPV DNA as indicated by dark purple stains in the epithelium of a condyloma acuminatum.

(A, From Habif TP, et al: Skin disease: diagnosis and treatment, ed 3., St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35 have an infrequent association with genital warts and a more common association with dysplasia and carcinoma of the cervix. These intermediate and high-risk HPV types also contribute to the development of squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (Bowen’s disease) of the genitalia.

Laboratory Findings

HPV does not grow in cell culture, and serologic tests are not routinely performed, in part because 90% of infected persons become HPV-seronegative within 2 years. Therefore, lesions of condyloma acuminatum should be biopsied and examined microscopically, if the clinical diagnosis is uncertain. The microscopic appearance consists of a sessile base, with raised epithelial borders, a thick spinous spinosum layer (acanthosis), and hyperkeratosis. Identification of HPV within the lesion confirms the diagnosis. This is achieved with the use of FDA-approved tests that use RNA probes to detect viral DNA specific to HPV genotypes (see Figure 13-10, C). Viral subtyping can be important for determining risk for carcinogenesis when cervical tissue and an abnormal Papanicolaou smear are involved (see Chapter 26 under “ Cervical Cancer”).

Medical Management

The HPV vaccine (Gardasil) was introduced in 2006. This quadrivalent vaccine is 95% to 100% effective in preventing infection with HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. Shortly after, a bivalent vaccine (Cervarix) was introduced. It protects against HPV types 16 and 18.49 Both vaccines have been approved for use in girls and women aged 9 to 26 years and is administered in a 3-shot regimen over a 6-month period. Gardasil is also offered to young men.1 These vaccines are highly effective for preventing infection by high-risk HPV types, thereby curtailing the major risk for cervical cancer associated with these types. They are most beneficial if administered before the onset of sexual activity. Of note, they have not been shown to eliminate or cure HPV infection, and they do not work against all HPV types.

HPV-induced genital warts can be completely removed with chemicals, antiviral drugs, or surgery. The best response is attained with small warts that have been present for less than 1 year. The CDC1 recommends podofilox 0.5% (Condylox) as the medication of first choice. It causes necrosis by arresting cells in mitosis. This patient-applied medication should be used twice a day for 3 days, with no treatment given for the next 4 days and the cycle repeated up to four times. Alternatively, the patient may apply imiquimod (Aldara) 5% cream at bedtime, three times per week or sinecatechins 15% ointment. Most warts dissipate within 3 months. Other available therapies include surgery (excision, cryotherapy, laser), weekly provider-applied podophyllin 10% to 25% in tincture of benzoin, or bichloroacetic/trichloroacetic acid 80% to 90%. Topical and intralesional therapy with 5-fluorouracil, an antimetabolite, has resulted in a greater than 60% response rate,50 and cidofovir is an antiviral that yields an effective response. Intralesional interferon is an option, but it is rarely recommended because of cost and adverse effects. Recurrences are common despite the use of first-line therapies (in about 10% to 25% of cases, generally within 3 months), even when the entire lesion, including the base, is removed. As with all STDs, treatment should include the patient’s sexual partner to avoid reinfection, as well as counseling regarding methods for reducing transmission. Without treatment, lesions may enlarge and spread. Spontaneous regression occurs in about 20% of patients.44

Dental Management

Medical Considerations

The dental management of patients with an STD begins with identification. The obvious goal is to identify all people who have active disease in order to limit the spread of the infection and the adverse outcomes of disease progression. Unfortunately, this is not possible in every case, because some persons will not provide a history or may not demonstrate significant signs or symptoms suggestive of their disease. The inability of clinicians to identify potentially infectious patients applies to other diseases as well, such as HIV infection and viral hepatitis. Therefore, it is necessary for all patients to be managed as though they were infectious. The U.S. Public Health Service, through the CDC, has published recommendations for standard precautions to be followed in controlling infection in dentistry that have become the standard for preventing cross-infection51 (see Appendix B). Strict adherence to these recommendations will, for all practical purposes, eliminate the danger of disease transmission between dentist and patient.

Even though these procedures are followed, several aspects of disease transmission specific to particular STDs warrant consideration. Box 13-2 presents a summary of such dental considerations.

Box 13-2 Dental Management of the Patient Who Has a Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD)

P: Patient Evaluation and Risk Assessment (see Box 1-1)

Potential Issues or Concerns

Reduce risk of transmission using standard infection control procedures*

• Gonorrhea—Little threat of transmission to dentist; oral lesions are possible

• Syphilis—Untreated primary and secondary lesions infectious; blood also is potentially infectious

• Genital herpes—Little threat of transmission to dentist; oral lesions (possible from autoinoculation) are infectious and can recur after trauma or stress

• HPV infection—Little threat of transmission to dentist; oral lesions are possible

Followup: Persons with sexually transmitted disease (STD) are at risk for human immunodeficiency virus [6] infection—testing is advised. Also, new cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) should be reported to the local/state health department.

* Because many patients with an active STD (as well as with other infectious diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis B) cannot be identified by the dentist, all patients should be considered potentially infectious and should be managed with the use of standard precautions. Preventive measures should be implemented that include patient education, as well as evaluation, treatment, and counseling of sexual partners.

Gonorrhea

The patient with (nonoral) gonorrhea poses little threat of disease transmission during dental procedures. This limited infectivity reflects the specific requirements for transmission as well as the early reversal of infectiousness with the institution of antibiotics. Patients in this category can receive dental care within days of beginning antibiotic treatment.

Syphilis

Lesions of untreated primary and secondary syphilis are infectious, as are the patient’s blood and saliva. Even after treatment has begun, its absolute effectiveness cannot be determined except through conversion of the positive result on serologic testing to negative; however, early reversal of infectiousness is expected after antibiotic treatment has been initiated. The time required for this conversion varies, ranging from a few months to longer than a year. Therefore, patients who are currently under treatment or who have a positive STS result after receiving treatment should be viewed as potentially infectious. Still, any necessary dental care may be provided with adherence to standard precautions, unless oral lesions are present. Dental treatment can commence once oral lesions have been successfully treated.

Genital Herpes

Localized uncomplicated genital herpes infection poses no problem for the dentist. In the absence of oral lesions, any necessary dental work may be provided. If oral lesions are present, elective treatment should be delayed until lesions scab over, to avoid inadvertent inoculation of adjacent sites. Antiviral agents may be required to prevent recurrence after dental treatment has been provided.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Patients with infectious mononucleosis may come to the dentist because of oral signs and symptoms. Clinical findings of fever, sore throat, petechiae, and cervical lymphadenopathy necessitate further assessment to establish a diagnosis of the underlying condition. Screening clinical laboratory tests can be ordered by the dentist (complete blood count [CBC], heterophil [Monospot] antibody test, and EBV antigen testing), or the patient may be referred to a physician for evaluation and treatment. Routine dental treatment should be delayed for about 4 weeks until the patient has recovered, the patient’s liver is capable of normal metabolism of drugs, and the blood count, spleen, and immune system have returned to normal.

Human Papillomavirus Infection

Although presence of genital condylomata acuminata does not affect dental management, oral warts are infectious, and standard precautions apply during oral dental procedures. The presence of oral lesions necessitates referral to a physician to rule out genital lesions in the patient or any sexual partner. Excisional biopsy or antivirals is recommended for HPV oral lesions.

Patients with a History of Sexually Transmitted Disease

Patients who have had an STD should be assessed carefully. They are at increased risk for additional STDs and recurrent infection. The clinician should ensure that adequate treatment was provided for any previous infection and that new infections have not developed. Special attention should be given to unexplained lesions of the oral, pharyngeal, or perioral tissues. Also, a review of systems may reveal urogenital symptoms. Patients with a history of gonorrhea or syphilis should report a history of antibiotic therapy. Patients treated for syphilis should receive a periodic STS for 1 year to monitor conversion of results from positive to negative. Adequate medical follow-up care should have been provided; if it was not, consultation and referral to a physician should be considered.

Patients with Signs, Symptoms, or Oral Lesions Suggestive of a Sexually Transmitted Disease

In patients who have signs or symptoms that suggest an STD, or who have unexplained oral or pharyngeal lesions, further assessment is indicated. The index of suspicion should be higher if the patient is between 15 and 29 years of age and has risk factors such as being an urban dweller, being single, and belonging to a lower socioeconomic group. Any patient who has unexplained lesions should be questioned about possible relationship of the lesions to past sexual activity and should be advised to seek medical care. Herpetic lesions in or around the oral cavity should be recognizable. Patients with oral herpes lesions should not receive routine dental care but should be given palliative treatment only. For a severe primary oral infection or for infectious mononucleosis, the patient may require specific therapy and referral to a physician.

Treatment Planning Modifications

No modifications in the technical treatment plan are required for a patient with an STD. No adverse interactions have been reported between the usual antibiotics or drugs used to treat STDs and drugs commonly used in dentistry. No drugs are contraindicated. Patients with Hutchinson’s incisors due to congenital syphilis may request aesthetic repair of affected anterior teeth.

Reporting to State Health Officials

Dentists should be aware of local statutory requirements regarding reporting STDs to state health officials. Syphilis, gonorrhea, and AIDS are diseases that must be reported in every state. Local health departments and state STD programs are sources of information regarding this issue.

Oral Manifestations

Gonorrhea

The presentation of oral gonorrhea is infrequent, nonspecific, and varied—that is, it may range from acute and severe ulceration with a pseudomembranous coating to slight or diffuse erythema of the oropharynx. Lesions of oral gonorrhea may closely resemble the lesions of erythema multiforme, bullous or erosive lichen planus, or herpetic gingivostomatitis, and have been reported to cause necrosis of the interdental papillae, lingual edema, edematous tissues that bleed easily, vesiculations, and a pseudomembrane that is nonadherent and leaves a bleeding surface on removal. Lesions may be solitary or widely disseminated. Lesions usually develop within 1 week of contact with an infected person; often, a history of fellatio is reported.8,52 With involvement of the oropharynx, patients report a sore throat, and the mucosa becomes fiery red, with tiny pustules and an itching and burning sensation (Figure 13-11). Symptoms also include an increased salivation, bad taste, fetid breath, fever, and submandibular lymphadenopathy. When the tonsils become involved, they are invariably enlarged and inflamed, with or without a yellowish exudate. The patient may be asymptomatic or incapacitated, with limited oral function (eating, drinking, talking), depending on the degree of inflammation. Diagnosis of oral lesions should be attempted with a smear and Gram stain, followed by confirmatory tests.

The initial step in treatment is to ensure that the patient is under the care of a physician and is receiving proper antimicrobial therapy. Thereafter, treatment of oral lesions is symptomatic (see Appendix C). The patient should be assured that oral infection will resolve with the use of appropriate antibiotics.

Syphilis

Syphilitic chancres and mucous patches usually are painless, unless they become secondarily infected. Both of these lesions are highly infectious. The chancre begins as a round papule that erodes into a painless ulcer with a smooth grayish surface (see Figure 13-4). Size can range from a few millimeters to 2 to 3 cm. A key feature is lymphadenopathy that may be unilateral. The intraoral mucous patch often appears as a slightly raised, asymptomatic papule(s) with an ulcerated or glistening surface. The lips, tongue, and buccal or labial mucosa may be affected. Both the chancre and the mucous patch (see Figure 13-5) regress spontaneously with or without antibiotic therapy, although chemotherapy is required to eradicate the systemic infection. The gumma is a painless lesion that may become secondarily infected. It is noninfectious and frequently occurs on and destroys the hard palate. Interstitial glossitis, the result of contracture of the tongue musculature after healing of a gumma, is viewed as a premalignant lesion. Oral manifestations of congenital syphilis include peg-shaped permanent central incisors with notching of the incisal edge (Hutchinson’s incisors) (see Figure 13-6), defective molars with multiple supernumerary cusps (mulberry molars), atrophic glossitis, a high-arched and narrow palate, and perioral rhagades (skin fissures).

Genital Herpes

HSV-1–induced ulcers are more common in the oral cavity than are those caused by HSV-2; however, these lesions cannot be differentiated clinically, and both should be treated similarly with antiviral agents (see Box 13-1 and Appendix C). Oral and perioral herpetic lesions are infectious during the papular, vesicular, and ulcerative stages, and elective dental treatment should be delayed until the herpetic lesion has completely healed. Dental manipulation during these infectious stages poses risks of (1) inoculation to a new site on the patient, (2) development of infection in the dental care worker, and (3) aerosol or droplet inoculation of the conjunctivae of the patient or of dental personnel. Once the lesion has crusted, it can be considered to be relatively noninfectious.

A problem of particular concern to dentists is herpetic infection of the fingers or nail beds contracted by dermal contact with a herpetic lesion of the lip or oral cavity of a patient. The infection is called a herpetic whitlow, or a herpetic paronychia (Figure 13-12). It is serious, debilitating, and recurrent. Herpetic whitlow can be triggered to recur by trauma or vibration from operating dental handpieces. Also, asymptomatic HSV shedding at oral or nonoral sites can trigger erythema multiforme, a mucocutaneous eruption characterized by “target” papules and ulcers that results from an immune response to the virus.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Head, neck, and oral manifestations of infectious mononucleosis include fever, severe sore throat, palatal petechiae, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Lymph nodes in the anterior and posterior cervical chain often are enlarged and tender to palpation. After recovery, EBV is associated with the development of oral hairy leukoplakia, a benign entity, as well as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Human Papillomavirus Infection

Condylomata acuminata commonly occur on the ventral tongue, gingiva, labial mucosa, and palate (see Figure 13-10, B). Transmission occurs by direct contact with infected anal, genital, or oral sites, or by self-inoculation. Lesions can be surgically excised, chemically removed with podophyllin, or laser-ablated. Caustic chemicals such as podophyllin are to be used with great caution to avoid damage to adjacent uninfected tissue, and should be rinsed off several hours after application. In addition, high-speed evacuation should be used during laser therapy to avoid inhalation of the virion-laden plume which can lead to laryngeal condylomata.53

The dentist also should be cognizant that a condyloma identified in children raises the suspicion for sexual child abuse when autoinoculation by hand-to-genital contact, nonsexual contact, or maternal fetal transmission has been ruled out. Failure to report signs of an STD to state health officials is a legal offense in some states. Tonsillar and base of the tongue squamous cell carcinomas are associated with high-risk HPVs.54

1 Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2 2009 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/tables/21b.htm.

3 Gwanzura L, McFarland W, Alexander D, Burke RL, Katzenstein D. Association between human immunodeficiency virus and herpes simplex virus type 2 seropositivity among male factory workers in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 1998;177(2):481-484.

4 Deguchi T, Nakane K, Yasuda M, Maeda S. Emergence and spread of drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Urol. 2010;184(3):851-858. quiz 1235

5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States: 2009 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia and Syphilis. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/trends.htm.

6 STD Statistics for the USA.. http://www.avert.org/std-statistics-america.htm.. Accessed March 14, 2011

7 McAdam AJ, Sharpe AH. Infectious diseases. In Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J, editors: Robbins and Cotran’s pathologic basis of disease, 8th ed, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2010.

8 Balmelli C, Gunthard HF. Gonococcal tonsillar infection–a case report and literature review. Infection. 2003;31(5):362-365.

9 Escobar V, Farman AG, Arm RN. Oral gonococcal infection. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13(6):549-554.

10 Summary of notifiable diseases, United States. 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;39(53):1-61.

11 Giunta JL, Fiumara NJ. Facts about gonorrhea and dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62(5):529-531.

12 Jamsky RJ, Christen AG. Oral gonococcal infections. Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53(4):358-362.

13 Kohn SR, Shaffer JF, Chomenko AG. Primary gonococcal stomatitis. JAMA. 1972;219(1):86.

14 Merchant HW, Schuster GS. Oral gonococcal infection. J Am Dent Assoc. 1977;95(4):807-809.

15 Schmidt H, Hjorting-Hansen E, Philipsen HP. Gonococcal stomatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1961;41:324-327.

16 Chue PW. Gonococcal arthritis of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;39(4):572-577.

17 Van Dyck E, Ieven M, Pattyn S, Van Damme L, Laga M. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by enzyme immunoassay, culture, and three nucleic acid amplification tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(5):1751-1756.

18 Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, Mwijarubi E, Klokke A, Senkoro K, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346(8974):530-536.

19 Syphilis Surveillance Profiles and Annual Reports – All Years. http://www.cdc.gov/std/Syphilis/syphilis-stats-all-years.htm.

20 McAdam AJ, Sharpe AH. Infectious diseases. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, editors. Robbins and Cotran’s pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2009.

21 Lowhagen GB. Syphilis: test procedures and therapeutic strategies. Semin Dermatol. 1990;9(2):152-159.

22 Little JW. Syphilis: an update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100(1):3-9.

23 Hook EW3rd, Marra CM. Acquired syphilis in adults. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(16):1060-1069.

24 Southwick KL, Guidry HM, Weldon MM, Mert KJ, Berman SM, Levine WC. An epidemic of congenital syphilis in Jefferson County, Texas, 1994-1995: inadequate prenatal syphilis testing after an outbreak in adults. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(4):557-560.

25 Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, Nahmias AJ, Aral SO, Lee FK, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(16):1105-1111.

26 Armstrong GL, Schillinger J, Markowitz L, Nahmias AJ, Johnson RE, McQuillan GM, et al. Incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(9):912-920.

27 Langenberg AG, Corey L, Ashley RL, Leong WP, Straus SE. A prospective study of new infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(19):1432-1438.

28 Nahmias AJ, Roizman B. Infection with herpes-simplex viruses 1 and 2. 3. N Engl J Med. 1973;289(15):781-789.

29 Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, Selke S, Zeh J, Corey L. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289(2):203-209.

30 Corey L, Wald A, Patel R, Sacks SL, Tyring SK, Warren T, et al. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(1):11-20.

31 Physician desk reference. http://www.pdr.net/.

32 Miller CS, Avdiushko SA, Kryscio RJ, Danaher RJ, Jacob RJ. Effect of prophylactic valacyclovir on the presence of human herpesvirus DNA in saliva of healthy individuals after dental treatment. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(5):2173-2180.

33 Ebell MH. Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(7):1279-1287.

34 Godshall SE, Kirchner JT. Infectious mononucleosis. Complexities of a common syndrome. Postgrad Med. 2000;107(7):175-179. 83-4, 86

35 Crawford DH, Macsween KF, Higgins CD, Thomas R, McAulay K, Williams H, et al. A cohort study among university students: identification of risk factors for Epstein-Barr virus seroconversion and infectious mononucleosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(3):276-282.

36 Lawee D. Mild infectious mononucleosis presenting with transient mixed liver disease: case report with a literature review. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(8):1314-1316.

37 Auwaerter PG. Infectious mononucleosis in middle age. JAMA. 1999;281(5):454-459.

38 Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1993-2000.

39 Balfour HHJr., Holman CJ, Hokanson KM, Lelonek MM, Giesbrecht JE, White DR, et al. A prospective clinical study of Epstein-Barr virus and host interactions during acute infectious mononucleosis. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(9):1505-1512.

40 Balfour HHJr., Hokanson KM, Schacherer RM, Fietzer CM, Schmeling DO, Holman CJ, et al. A virologic pilot study of valacyclovir in infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Virol. 2007;39(1):16-21.

41 Forcier M, Musacchio N. An overview of human papillomavirus infection for the dermatologist: disease, diagnosis, management, and prevention. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(5):458-476.

42 Brown TJ, Yen-Moore A, Tyring SK. An overview of sexually transmitted diseases. Part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5 Pt 1):661-677. quiz 78-80

43 Koutsky L. Epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Am J Med. 1997;102(5A):3-8.

44 Ault KA. Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections in the female genital tract. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2006;2006(Suppl):40470.

45 Wiley D, Masongsong E. Human papillomavirus: the burden of infection. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(6 Suppl 1):S3-S14.

46 Cates WJr. Estimates of the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. American Social Health Association Panel. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(4 Suppl):S2-S7.

47 Munk C, Svare EI, Poll P, Bock JE, Kjaer SK. History of genital warts in 10,838 women 20 to 29 years of age from the general population. Risk factors and association with Papanicolaou smear history. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24(10):567-572.

48 Ahmed AM, Madkan V, Tyring SK. Human papillomaviruses and genital disease. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(2):157-165. vi

49 Moscicki AB. HPV vaccines: today and in the future. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(4 Suppl):S26-S40.

50 Swinehart JM, Skinner RB, McCarty JM, Miller BH, Tyring SK, Korey A, et al. Development of intralesional therapy with fluorouracil/adrenaline injectable gel for management of condylomata acuminata: two phase II clinical studies. Genitourin Med. 1997;73(6):481-487.

51 Cleveland JL, Bond WW. Recommended infection-control practices for dentistry, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42(RR-8):1-12.

52 Chue PW. Gonorrhea–its natural history, oral manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 1975;90(6):1297-1301.

53 Hallmo P, Naess O. Laryngeal papillomatosis with human papillomavirus DNA contracted by a laser surgeon. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;248(7):425-427.

54 Syrjanen S, Lodi G, von Bultzingslowen I, Aliko A, Arduino P, Campisi G, et al. Human papillomaviruses in oral carcinoma and oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2011;17(Suppl 1)):58-72.

55 Russel MG, Volovics A, Schoon EJ, van Wijlick EH, Logan RF, Shivananda S, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: is there any relation between smoking status and disease presentation? European Collaborative IBD Study Group. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4(3):182-186.

[/membership]