CHAPTER 12

Smile Osteotomy

After scientific discovery, nature’s enigmatic smile.

—O. Brekne

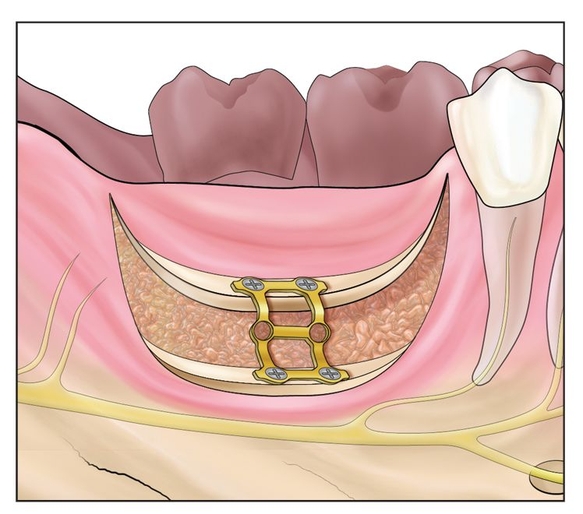

The atrophic, partially edentulous posterior segment of the mandible with a relatively prominent endosseous nerve location and uncertain prognosis for vertical onlay bone grafting can be treated with an osteoperiosteal flap that is designated the smile osteotomy. The smile osteotomy is a sandwich graft with a basal cut curved like a smile; the lowest part of the osteotomy is located 2 mm above the nerve, at the midpoint of the osteotomy, before the cut is tapered crestally both anteriorly and posteriorly.1

Surgical Technique

Surgical Technique

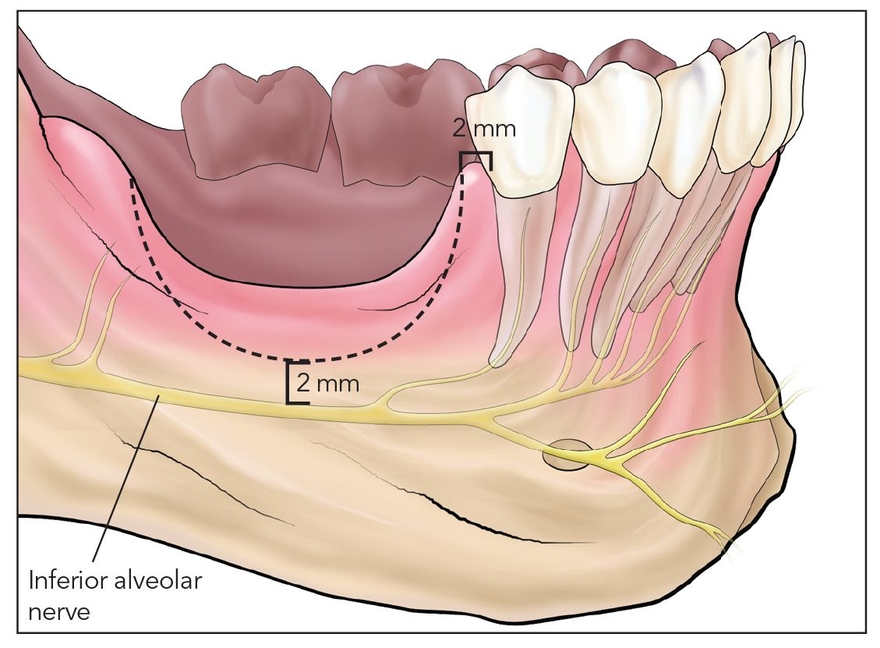

Following administration of local and intravenous anesthesia, a mouth prop is used to open the mouth on the opposite side to establish surgical access. A buccal vestibular incision is carried out about 5 mm below the attached gingiva along the length of the edentulous space to the retromolar pad; the mental foramen and associated nerve bundle must be carefully avoided (Fig 12-1a). The intraosseous nerve location is identified by using a computed tomography (CT) scan preoperatively to help design the osteotomy so that it can be performed without reflecting the flap too far crestally. (The osteotomy can be performed without any reflection of mucoperiosteum toward the crest.) The closest to the nerve that the osteotomy gets inferiorly should be in the center of the segment—about 2 mm above the nerve—before the cut tapers to the crest posteriorly and anteriorly. The anterior cut should stay about 2 mm from the most distal tooth root.

Fig 12-1a The posterior atrophic mandible often dips down vertically near the inferior alveolar nerve. A segmental osteotomy (dotted line) is designed in a curved shape, termed the smile osteotomy, that minimizes the proximity of the bony cut to the nerve.

Fig 12-1b The segment is cut at least 2 mm above the nerve using piezoelectric surgery (shallow) and an oscillating saw (deep).

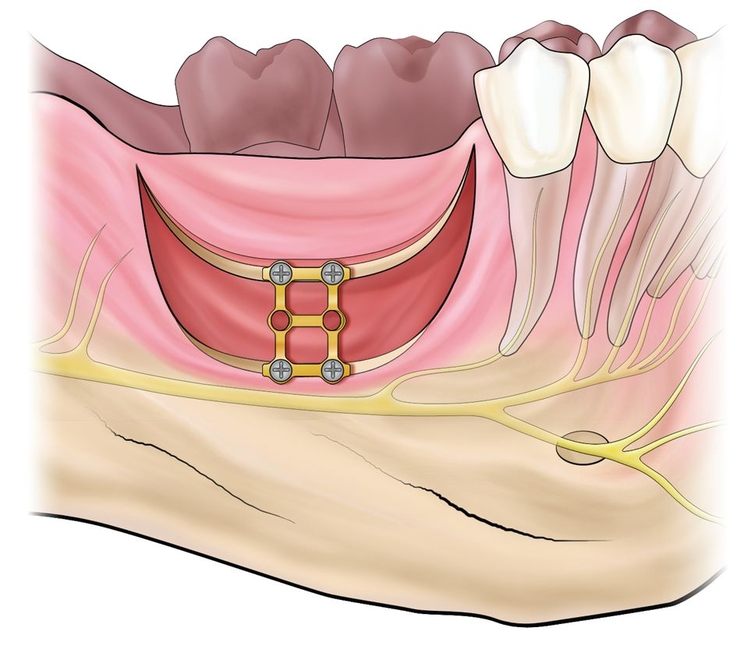

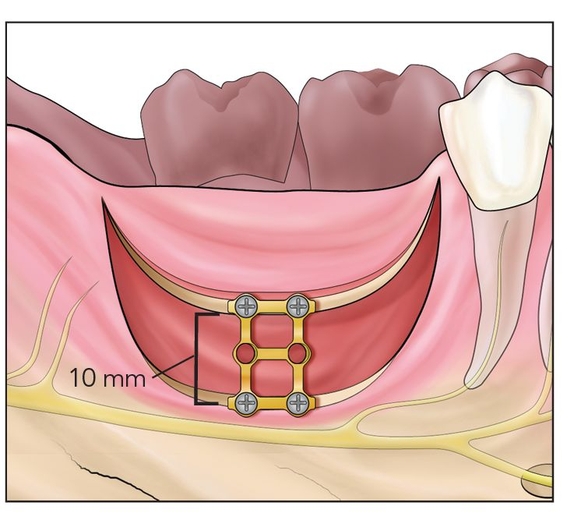

Fig 12-1c The segment is freed with an osteotome and elevated 5 to 10 mm vertically. A bone plate is placed to establish vertical height at the alveolar plane.

Fig 12-1d The bone plate is torqued to bring the alveolus into axial alignment and then interpositionally bone grafted with autograft or bone morphogenetic protein 2.

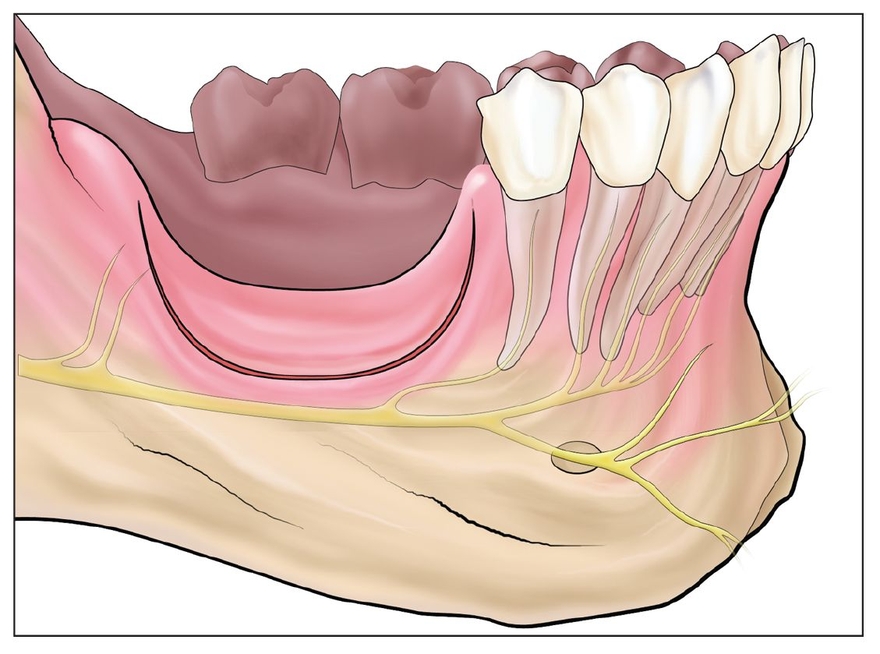

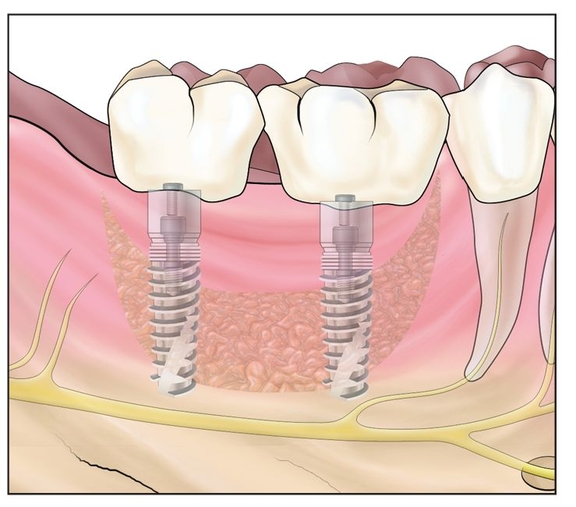

Fig 12-1e After 4 months of healing, implants are placed and later restored.

The initial smile-shaped cut can best be made with a piezoelectric knife to a depth of about 5 mm. The use of piezoelectric surgery is a good idea to delineate the osteotomy cut and to help avoid nerve injury. Once the smile-shaped lateral osteotomy cut is delineated, a sagittal saw is used to cut deeper to free the lingual plate (Fig 12-1b). The piezoelectric knife may not be well irrigated and cooled sufficiently to allow osseous cuts at />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses