12

Rehabilitation of the worn dentition

In general, there are few objective criteria for evaluating the need for prosthodontic treatment, but toothwear-based criteria may be the exception. For most people, toothwear is a natural part of ageing, and replacement of lost tooth substance is only infrequently a necessity. Even patients with extensively worn dentitions do not automatically require oral rehabilitation if their functional adaptation is good. But if the toothwear is considered to be so severe or its rate of progression threatens, for example, endodontic integrity, that rehabilitation is indicated, there are several possibilities for treatment.

This chapter reviews the evolution of rehabilitative concepts and techniques from the traditional approach to ones that are increasingly favoured today. Wherever possible, the account given is based on an appraisal of the available literature (Johansson et al. 2008). Realistically, however, the literature on toothwear provides very little scientific evidence that can be said to support unambiguous recommendations about its management. The question of what the best approach to rehabilitation of given toothwear scenarios is, is therefore often based on evidence of lower scientific strength than randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Within the general scheme of a book on toothwear, the title of this chapter would, to most readers, suggest an account of the rehabilitation of the severely worn dentition. It would likely also imply the severe loss of predominantly posterior occlusal, but also anterior palatal, tooth substance, with the host of clinical challenges related to the management of such conditions. The approach to rehabilitation has traditionally been an ‘all-or-none’ one, which – once the need for treatment has been decided – uses invasive, irreversible and, in most cases, clinically and technically demanding full-mouth reconstruction. The net result of this has been a complex decision-making process with a tendency to defer treatment until the toothwear is well advanced.

The fact that erosive toothwear is increasingly seen in younger individuals has, in more recent times, seen the emergence of another treatment approach. The method focuses on meeting greater aesthetic demands while also being conservative of further tooth substance reduction and showing favourable longevity in early reports. The most severe lesions that affect the occlusion occur on the occlusal surfaces of the first permanent molars and the palatal surfaces of the upper central incisors, as discussed in Chapter 10. It follows that there are vertical as well as horizontal dimensions to the resultant toothwear (Johansson 2002). A better understanding of this characteristic localisation of toothwear and how its subsequent effect on the occlusion complicates rehabilitation has prompted the development of specific treatment methods that aim to address the problem through more conservative, and frequently site-specific, solutions. Increasingly, these techniques are applied to older patients who would otherwise have been treated with conventional prosthodontic methods. Besides the rehabilitative challenges posed by occlusal and palatal toothwear, erosion is suggested to be the primary aetiological factor for non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs). The term ‘degradation’ has been used to describe the presence of such lesions together with occlusal wear (Khan et al. 1999), and presents another dimension to the rehabilitative challenge.

There is now recognition that early diagnosis of toothwear is possible and a proper investigation of its aetiology a necessity. Frequently, although not invariably, this will result in preventing, or at least slowing, further damage. However, even as our understanding of the aetiology and pathogenesis of toothwear gradually increases, it remains some way off the level of knowledge that exists about other comparable dental conditions, such as dental caries. Such limitations add to the management complexities, especially with regards to rehabilitation. Fortunately, there are a number of promising, and some would say alluring, developments towards more conservative treatment approaches afforded by, albeit still limited, research as well as rapid developments in dental materials science.

PRINCIPLES AND STRATEGIES FOR REHABILITATING WORN DENTITIONS

The clinical challenge

Toothwear is generally slowly progressive, and its early signs do not inevitably lead to further deterioration. Any symptoms or patient dissatisfaction is similarly slow to present. The unpredictability of the rate and the likely periodicity of progression will, on an individual basis, have therapeutic implications. Its irreversible nature and multifactorial aetiology make toothwear one of the most difficult clinical problems to deal with. An especially vexing aspect of toothwear is that because most dentists examine patients for the first time at an unknown point in its progression, a dilemma arises regarding the decision to intervene restoratively and/or prosthodontically, or not. Precisely what an acceptable severity and rate of wear is, is not easy to decide, but such a judgement should always be individually evaluated. Consideration should be given to the age and life expectancy of the individual, as well as aetiological factors and host defence mechanisms that may be operating (see Chapter 8). At the same time, one has to consider the risk of ‘supervised neglect’ of the patient’s condition (Bartlett 2010). Early diagnosis and awareness on the part of the patient of an unacceptable level of wear would appear to be key to prevention and management.

Management strategies

The definitive treatment of toothwear can be performed in a number of different ways. However, its broader management is an inclusive process, comprising a thoroughly methodical clinical examination and assessment of possible causative factors, including a systematic history, diagnoses, prevention, monitoring and, in some cases, definitive rehabilitation. In an article that sought to present some clinical guidelines, its authors cautioned, ‘There are no hard and fast rules and the need for treatment should be established after considering: the degree of wear relative to the age of the patient; the aetiology; the symptoms; the patient’s wishes’ (Davies et al. 2002). On the basis of current knowledge, there is little reason to contest this statement from almost 10 years ago.

On the basis of the history, clinical examination and diagnosis, management should be directed towards first eliminating the aetiological factors and strengthening any modifying factors. Since toothwear is usually a relatively slow process, urgent restoration will, in many patients, not be necessary. Proceeding with caution is important especially for younger individuals since the longevity of restorations is finite and frequently quite limited. However, for a patient suffering from demonstrably progressive wear or severe sensitivity or pain, it becomes important to hasten the investigatory phase in order to retard or prevent further deterioration or symptoms.

Rehabilitative considerations

The question of rehabilitation arises when the patient’s needs, severity of the wear and potential for unacceptable progression are of concern. There is no evidence that the presence of toothwear will inevitably lead to severe wear, with fluctuations in its rate of progression making it difficult to estimate future deterioration. Costly conventional prosthodontics was, and still is, the mainstay of rehabilitation of the severely worn dentition when treatment is indicated. Such treatment is also complex and generally highly invasive. As has already been mentioned, the tendency has, therefore, been to defer it if at all possible, with the result that wear was usually well advanced by the time definitive restorative treatment was commenced. On the other hand, there are those who advocate early diagnosis and timely treatment ‘to prevent the tooth from wear beyond a point of acceptable restoration’ (Dawson 2007).

Besides the traditional ‘subtractive’ approach to rehabilitation of the worn dentition, a gradual shift towards greater conservatism by an ‘additive’ approach seems to be under way in the form of direct and indirect resin composite restorations (see Chapter 11), bonded cast metal restorations, implant-supported removable partial dentures (RPDs), orthodontic treatment and protective splints, amongst others. While this trend may be more apparent in some parts of the world than in others, the rationale for it and the developments in dental materials science and more reliable accompanying clinical techniques are both relevant and promising. More about these developments is discussed later in the chapter.

As regards the efficacy of any one of the aforementioned treatment options or comparisons among them, a recent search of the literature on rehabilitation of toothwear (covering the period up to November 2007) was unable to identify a single paper with an RCT design (Johansson et al. 2008). In preparing for this chapter, a further literature search was performed using the same parameters as in our previous report, and this again failed to identify any paper on the topic as at May 2010. A systematic review similarly failed to find any support for the efficacy of any one occlusion-based treatment modality over another (van’t Spijker et al. 2007), and it can be concluded that there are no sufficiently robust, documented outcomes regarding different approaches to the rehabilitation of the worn dentition.

However, even though the RCT is considered the most reliable design for evaluating the effectiveness of treatment, just as in most other areas of dentistry, RCTs are rarely found in prosthodontics. It has been reported that RCTs made up only 1.7% of all articles in the three leading prosthodontic journals between 1990 and 1998 (Dumbrigue et al. 1999), and even then many are judged to be of poor methodological quality (Jokstad et al. 2002). More recently, it was reported that most RCTs on implant dentistry had inadequate randomisation procedures (Dumbrigue et al. 2006). Even systematic reviews on the prosthodontic treatment options for single-tooth replacement have concluded that a lack of comparable comparative studies limits any clear recommendations from being made (Salinas & Eckert 2007; Torabinejad et al. 2007). Bearing such constraints in mind, the discussion and recommendations that follow are necessarily based on studies whose designs are considered to be of less scientific rigour than RCTs, on the opinions of respected authorities and on our own clinical experience.

Dentoalveolar compensation

Severe occlusal toothwear may result in changes to the occlusal vertical dimension (OVD), with a possible increase in interocclusal space. This potentially has significant implications for rehabilitation. It has been shown that dentoalveolar compensation may cause the OVD to remain relatively constant, or even increase, despite toothwear. This would mean that any re-establishment of OVD (for the purpose of restoring facial height, for example) would not ordinarily be a de facto part of rehabilitation.

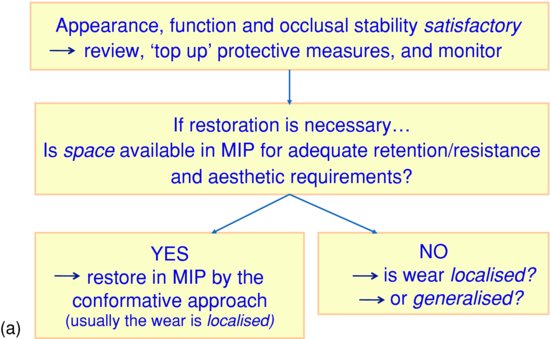

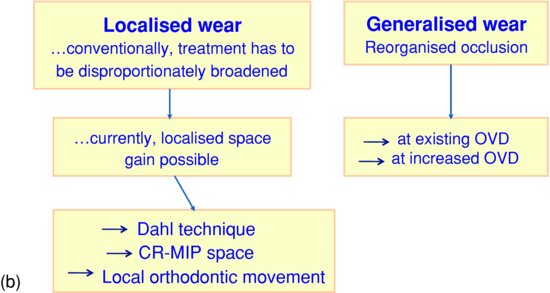

Instead, the important question, if rehabilitation is necessary, will be whether sufficient interarch restorative space required for restorations that also meet aesthetic requirements is available in the maximum intercuspal position (MIP) and whether retention and resistance, particularly so for conventionally cemented restorations, will be adequate. If such ‘restorative space’ exists, restoration in MIP is probably going to be relatively straightforward using a conformative approach (Wise 1977). If, on the other hand, there is not sufficient space, the next question will be whether the wear is largely localised or generalised (Fig. 12.1a). For localised wear, vertical space can be gained by reversing the effects of dentoalveolar compensation using the ‘Dahl technique’ (Dahl et al. 1975; Chapter 10). In this regard, it will be recalled that the most severe lesions that affect the occlusion occur on the occlusal surfaces on the first permanent molars and the palatal surfaces of the upper central incisors. Passive eruption of upper molars and lower incisors then introduces both vertical and horizontal changes to alter the occlusal plane. Although this complicates rehabilitation, the ‘Dahl technique’ is capable of addressing it in a relatively simple way. By this means, treatment is confined to the worn teeth and avoids it being disproportionately broadened to more teeth (which may well be unaffected by wear) than necessary (Fig. 12.1b). Several modifications of the technique have been described following the original report, including placement of single or multiple bonded restorations at increased OVD in anticipation of rapid re-establishment of full intercuspation being attained by the non-occluding teeth (Poyser et al. 2005). Orthodontic treatment is increasingly common in adults, and several types of tooth movements, including selective intrusion or extrusion, may be provided for the purpose of increasing interocclusal ‘restorative space’ in the anterior region, but increasingly also in localised posterior sites.

Figure 12.1 Interocclusal restorative space considerations once treatment has been decided upon: (a) Implications of space adequacy or inadequacy; (b) approaches that can be used when space is not adequate for restorative purposes.

Generalised wear, on the other hand, will in most cases require a reorganised approach (Wise 1977), with or without an increase in OVD, and this is discussed later (Fig. 12.1b).

Biomechanical factors

When conventional fixed prosthodontic rehabilitation is necessary, extensive tooth preparation is invariably going to be needed. This raises a paradox whereby more tooth substance removal is needed in the therapeutic pursuit of making good the damage caused by a process of tooth substance loss itself. The difficulty of achieving adequate mechanical retention and resistance forms for conventionally cemented restorations, and the potentially greater load on restorations if there is bruxism, heavy chewing forces or unfavourable loading directions between teeth means that caution is needed in the design of restorations.

Single crowns should be provided whenever possible and fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) should be of minimal extension. Nevertheless, many restorations fail as a result of stress concentration from differential wear and poorly planned occlusal contacts, a risk that is greater if there is heavy loading, perhaps ‘directly’ through bruxism or ‘indirectly’ if there are few remaining occluding units. Inadequate retention and resistance of crowns on short abutments can be improved in several ways (Box 12.1).

Box 12.1 Methods of improving retention and resistance for conventionally cemented restorations.

- Extending the finish line apically

- Preparing vertical grooves or boxes with parallel sides

- Including parallel pins in the preparation

- Preparing occlusal pits with parallel walls

- Crown-lengthening surgery

- Use of resin-based cements

Increasing the length of a short clinical crown and extending the finish line apically can be achieved by crown-lengthening surgery, which implies removal of parts of the periodontal tissues, with or without osseous recontouring (Fig. 12.2). Elective devitalisation of a tooth in order to place a post and core should be considered only when there is no other way to increase retention and resistance form as vital teeth (perhaps even short ones) generally survive longer as abutments than ones that are endodontically treated (de Backer et al. 2007). Fortunately, the techniques of surgical crown lengthening and devitalisation that were once popular seem to be abating as non-preparation, adhesive-bonding techniques, as well as techniques that regain vertical space by reversing the effects of dentoalveolar compensation are developed.

Figure 12.2 Surgical crown lengthening of worn maxillary anterior teeth prior to provision of metal–ceramic crowns: (a) inverse bevel incision prior to raising mucoperiosteal flap; (b) sutured mucoperiosteal flap after osseous recontouring; (c) one-week postsurgical condition shows adequate clinical crown length to allow appropriate abutment preparation and restoration. (Courtesy of Dr. Fadel Kamber, Kuwait University, Kuwait.)

Splinting should be avoided whenever possible, and is not recommended in cases of confirmed bruxism. Similarly, splinting additional abutments in order to compensate for a short, poorly retentive primary abutment is contraindicated: the risks of cementation failure followed by secondary caries or mechanical problems, such as fracture of porcelain or connectors, rather than being reduced, will probably be as great at the short abutment, irrespective of the inclusion of secondary abutments. Thus, physiological tooth mobility will be unrestrained, torquing forces minimised, and in case of cementation failure, the condition easily detected and more easily correctable.

It is often suggested that occlusal splint therapy should be provided in the form of a full-coverage appliance overlaying the restored teeth. In spite of its frequent use in such a manner and strong recommendation by some authorities (Dawson 2007), there is no evidence about the effectiveness of occlusal splints to prevent future restorative failure.

Conventional rehabilitative techniques

For clarification, this section refers to prosthodontic methods that were considered standard before the era of adhesives. That being said, it is reasonable to assert that traditionally, restorative techniques developed in response to the need to restore teeth damaged by dental caries. The greater the carious damage, the greater was the complexity of the restoration called for, and when direct restorative techniques were no longer capable of fulfilling restorative objectives, full-coverage indirect restorations could both restore and protect the weakened tooth. Strict adherence to the principles of tooth preparation and technical precision were considered essential for the success of such restorations.

Although the severity of caries may, after its excavation, sometimes result in a tooth that resembles a severely worn tooth (in terms of quantity of substance loss), the morphological features are generally quite different: one of the most striking differences is short clinical crowns in severely worn teeth. Yet the very same fixed prosthodontic methods, in the absence of any obvious alternative, have been almost identically applied to rehabilitating the severely worn dentition. Although the strategies needed to rehabilitate a severely worn dentition would seem to be different from those needed for teeth that are relatively unworn, the ingenuity of salvage techniques that have been used over the years has been impressive, adding to the quality of life of many patients. However, the methods are largely anecdotal and lack rigorous scientific scrutiny of their outcomes.

Conventional fixed restorations

Despite the lack of information on outcomes of conventionally cemented restorations to restore teeth damaged by toothwear, they are widely used, specifically full-coverage metal–ceramic restorations. They offer some flexibility as regards appearance, design of restoration and thus degree of tooth reduction required, as well as the possibility of replacing missing teeth.

In many cases, localised toothwear affects only the anterior segments. These are also the most commonly affected teeth, particularly so due to an erosive factor, and rarely would the complete dentition be equally affected. The problem of restoring worn anterior teeth when little available interocclusal space exists is apparent. In this regard, a less radical alternative to complete arch occlusal rehabilitation was first described by Dahl and coworkers (1975), as a two-stage process. To achieve this, a bite-raising removable anterior cobalt–chromium splint was originally utilised as the first stage. By this means, a combination of forced intrusion of anterior teeth and supraeruption of posterior teeth takes places, resulting in the re-establishment of initially opened posterior tooth contacts. Such an approach can greatly simplify and curtail treatment to only the affected anterior teeth (the second stage of the process), obviating the need for full-coverage restorations of frequently sound (albeit sometimes mildly worn) posterior teeth. The sequence of treatment is illu/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses