12

Prevention of oral diseases for a dependent population

INTRODUCTION

Frail elders, whether they reside in a long-term care facility or at home, have difficulty accessing timely and appropriate oral healthcare. (The terms “long-term care facility,” “residential care facility,” and “nursing home” are used to indicate collective residences where elders receive varying levels of assistance with daily activities and nursing care.) They face multiple challenges—limited physical and cognitive abilities, unclear values and priorities of caregivers, unstable politics and policies where they reside, sparse financial support, and doubtful jurisdictional control of care facilities (MacEntee, 2006). In the absence of insurance or personal resources, a large portion of the frail population will be unable to afford dental services, even if available. Publicly funded programs, such as Medicare in the United States, often do not provide adequate coverage for dentistry, and scarce finances are often spent transporting residents for emergency treatments when preventive care would be a more efficient use of funds. Clearly, there must be a response to the increasing oral health concerns of frail elders with special needs.

Even without physical, psychological, and financial limitations, many elders cannot access dentists or dental hygienists, either outside or within their residence. Therefore, the task of preventing disease usually falls to the nursing staff. However, dentistry and oral healthcare get scant attention in the education of most nurses and personal care-workers or care-aides. Current expectations are that “best available evidence” is based on randomized controlled trials to test all preventive and treatment strategies (Sanson-Fisher et al., 2007). However, expectations are not always met when evidence relates to real life-events that are impossible to control fully or to observe without bias.

In this chapter, we consider the factors affecting maintenance of oral health in frail elders at home and in residential care, and the success of programs designed to prevent oral diseases. We conclude with recommendations for future policy and service development.

BARRIERS TO MAINTAINING ORAL HEALTH FOR FRAIL ELDERS

Frailty and dependence

Frail elders in residential care in North America typically have three chronic diseases, take numerous medications daily, and feel more unhealthy when compared with elders who are living independently (Shay and Ship, 1995). Some of them are fatalistic about losing their teeth, while others are offended when their oral hygiene is criticized (Schou and Eadie, 1991). Nonetheless, when elders grow frail almost invariably they have unhealthy mouths and teeth, probably because of visual impairment, loss of manual dexterity, cognitive impairment, or depression (Chalmers et al., 2008). The impact of this neglect can have a very deleterious effect on general health, particularly relating to vascular and coronary heart diseases, diabetes, and pneumonia (Russell et al., 1999; Scannapieco et al., 2003; Khader et al., 2004; Department of Health, 2005; Jablonski et al., 2005; Osterberg et al., 2008). It is also likely that the psychological impact of dental disability precipitates depression, negative self-image, and difficulties communicating and eating, which leads to apathy and social withdrawal (Department of Health, 2005).

Cognitive impairment intensifies preexisting oral problems, and individuals with dementia typically have poor oral hygiene, poor diets, and higher levels of oral diseases (Chalmers et al., 2008). Mouth problems arise when the dementia precipitates verbal or physical aggression, and the elders refuse oral hygiene and other care, and they are exacerbated further when the elders are unable to explain their discomforts and wish for dental care (Shimazaki et al., 2004).

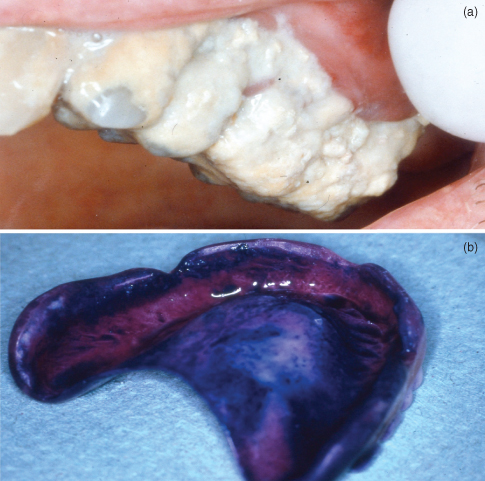

When severely disabled, there is a tendency for some residents to accept care passively. However, many carers lack knowledge, training, and basic skills for identifying oral problems or brushing a patient’s teeth (Frenkel, 1999; Fitzpatrick, 2000; Department of Health, 2005). It is not surprising, therefore, that assistance with oral hygiene is not readily available, nor that residents have dirty mouths as they grow frail and dependent (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Neglect of oral hygiene: (a) natural teeth covered with thick, mature plaque; (b) a denture thickly coated with disclosed, mature plaque.

Residents are frequently aware that their carers dislike or feel insecure with mouthcare, which increases their sense of vulnerability, heightens their concern about being a nuisance, and inhibits their requests for help (Frenkel, 1999). Consequently, even when their oral health is moderately good on admission, it can deteriorate rapidly if they are dependent on others for the routine of daily oral hygiene and access to dental treatment (Jablonski et al., 2005).

About three-quarters of the elders in residential care are cognitively impaired and require help with three or more basic activities, such as bathing, dressing, toileting, or feeding (Jablonski et al., 2005). It is no surprise, therefore, that they need assistance to visit a dentist, and that they encounter physical barriers, such as difficult access to the dental chair or to the toilet when at a treatment center and despite the legislation supporting disabled people in many countries.

Finances

For retired people on low or restricted incomes, financing dental care is a significant problem. The culture of older generations often leads them to avoid physicians and dentists, except as a last resort (MacEntee et al., 1999). Some elders in residential care cannot decide whether or not to have dental treatment, and occasionally, their relatives offer little encouragement because treatment seems unnecessary and expensive. Furthermore, in most countries, dentistry is not included as a benefit of medical insurance (Shay and Ship, 1995), and state-funded dental benefits, especially those with fee exemptions for people with low income, provide very limited care that is poorly understood by potential recipients (Jablonski et al., 2005).

There are many different social insurance systems and different payment methods for dentistry. For example, in Switzerland, dentistry is not insured, and everybody pays a fee for service unless they have a very low retirement income, which the state supplements with limited financial support for health services. In Germany, the Legal Social Insurance, which covers 95% of the population, pays for dental extractions, apicectomies, endodontics, composite and amalgam restorations, radiological examinations, and partial reimbursement of prosthodontic fees. Government Web sites usually contain information about the current regulations in force in individual jurisdictions.

Knowledge, attitudes, and training of dentists and carers

Professional limitations of dentists

There are dentists who manage the decline and death of their patients very effectively, even though death and dying are not normally part of their usual experiences (Nitschke et al., 2005). But there are many others who have difficulty coping with frail patients, especially if they have to leave the familiarity of a well-equipped dental clinic to attend elders who are frail and bedridden at home or in a long-term care facility (MacEntee et al., 1991; Bryant et al., 1995). Residential care administrators complain occasionally that dentists lack kindness, compassion, patience, and professional skills to treat residents with dementia and behavioral problems (Chalmers et al., 2001). Indeed, dentists receive very limited education in managing patients, whether young or old, who are physically or cognitively disabled (Chalmers et al., 2001; Department of Health, 2005; Nitschke et al., 2005). Furthermore, dentists generally are uninterested in residential care and its administrative complexities, and hesitate to work in unfavorable conditions for financial returns that are less than they receive in their more controlled and familiar clinics (MacEntee et al., 1999; Simons, 2003; Chalmers et al., 2001; Nitschke et al., 2005).

Nursing staff

Responsibility for daily mouthcare as an integral part of healthcare generally lies with nursing staff and care-aides or care-workers. Yet, there are barriers to fulfilling this responsibility, including lack of knowledge and training, general anxiety about causing harm to a resident’s mouth, uncooperative residents, lack of time, staff shortages, and lack of appropriate supplies such as toothbrushes and toothpaste (Eadie and Schou, 1992; Weeks and Fiske, 1994; Chalmers et al., 1996; Wårdh et al., 1997; Frenkel, 1999; MacEntee et al., 1999). Furthermore, some nurses are misinformed about oral health, or they are unable to translate their knowledge into best practice (Hoad-Reddick and Heath, 1995). It is not uncommon for nurses and care-aides to use mouthwashes and swabs rather than toothbrushes and toothpaste when cleaning a patients teeth, and more often than not their knowledge about gingivitis and caries is poor (Weeks and Fiske, 1994; Adams, 1996). It is easier to remove and clean dentures than to brush natural teeth, although many nurses are uneasy about removing dentures from a patient’s mouth (Vigild, 1990; Frenkel et al., 2001; Grimoud et al., 2005; Nicol et al., 2005; Peltola et al., 2007), possibly because they feel that this is a threat to the resident’s privacy and dignity (Charteris and Kinsella, 2001). More likely, they are fearful of being bitten, or they avoid teeth because of their own traumatic experiences with dentistry (Frenkel, 1999). Residents who resist care by clamping lips together or by pushing away the carer’s hands are particularly unsettling for many carers. Usually, this reaction is precipitated by confronting a resident without warning, whereas a nonthreatening explanation of the intent or purpose of the care will go a long way to getting the resident’s cooperation and consent (Paley et al., 2004; Coleman and Watson, 2006). In general, mouthcare for elders who are demented can be a demanding and confusing task, which probably explains why most carers overlook oral hygiene as an essential part of daily hygiene (MacEntee et al., 1999).

Without doubt, there are many nursing facilities where the administrators and staff acknowledge the importance of a healthy mouth and the ideal of daily mouthcare for all (MacEntee et al., 1999). Consequently, appropriate training and clinical experience for nurses and care-aides should help enhance their knowledge and clinical skills for mouthcare, much as it helps overcome ignorance and prejudices around incontinence (MacDonald and Butler, 2007). Unfortunately, nursing practice of mouthcare falls well short of the ideal elsewhere, and nurses with their administrators tend to seek help from dentists and dental hygienists rather than involve themselves in the daily preventive care of their residents (Eadie and Schou, 1992; MacEntee et al., 1999). There are facilities where special training in mouthcare is dismissed as unnecessary because it is “just common sense” (Weeks and Fiske, 1994; Frenkel, 1999). There are also carers who rate the oral health of their residents as fair or poor, yet when asked they seem satisfied with the “fair or poor” oral care they provide (Wårdh et al., 1997; Pyle et al., 2005).

Nursing journals offer good advice on oral healthcare (e.g., Fitzpatrick, 2000), but nursing textbooks in general are woefully neglectful of dentistry and basic oral care (Furr et al., 2004). Student nurses in the United Kingdom and the United States, for example, receive on average about 1 h of oral health-related education, almost half of them receive no instruction at all, while less than 10% receive postqualification tuition in oral healthcare (Hoad-Reddick and Heath, 1995; Adams, 1996). The tuition offered is delivered usually by nurses who advocate little more than swabbing the inside of the mouth and teeth with lemon and glycerine or dilute hydrogen peroxide (Moore, 1995). It is very likely that the neglect of mouthcare for elderly patients reflects a general uneasiness about geriatric care and lack of good practical education in geriatrics among nurses, at least in North America (Baumbusch and Andrusyszyn, 2002; Koren et al., 2008). Nearly all nursing schools in the United States integrate gerontology in the course curricula, but less than half of them offer it as an elective, and only a quarter of them require students to take a course in gerontology (Grocki and Fox, 2004).

In the United Kingdom, “care of old people/geriatrics” is part of basic nurse training, but specialized gerontological qualifications can be obtained in work-related courses (e.g., Higher National Diploma, Higher National Certificate) or as a 3- to 4-year university-based bachelor’s degree; and in Germany, there is a 3-year training program leading to a certificate of geriatric nursing.

The emotional adjustments identified within the maternal relationship model of caring helps explain why some carers distance themselves from frail residents in whom they see a disturbing image of their own future (Edwards, 2008). The apathy of frail residents can also be used as an excuse for not bothering to offer assistance (Wårdh et al., 2002), while more alert residents can be discouraging by resenting or refusing offers of help from younger carers. The personal autonomy and independence of the residents is used also by carers as an excuse for not helping with mouthcare, but this is reasonable only if it supports the wishes of the resident. Indeed, occupational therapists should be consulted, if possible, when healthcare and personal autonomy are under review (Bellomo et al., 2005).

Care-aides

Long-term care-aides (also called care assistants) in most Western countries receive even less instruction about mouthcare than nurses, yet they work usually with minimal supervision and render most of the personal care for the residents (Chalmers et al., 1996; MacEntee et al., 1999). They are often recruited from immigrant populations whose culture and language can differ from the elders in their care. Moreover, they are a very mobile profession who may remain as carers only for short periods (Weeks and Fiske, 1994; Chalmers et al., 1996; Frenkel, 1999; Jablonski et al., 2005). Consequently, the mouthcare they provide can be very unpredictable and unstable.

Organizational barriers

Oral health policy, guidelines, and protocols

Administrators and managers of residential care facilities are concerned about the cost of dentistry, and they complain about the lack of information on the professional services available, along with apparent lack of interest among dentists and dental hygienists, and the need to transport residents out of the facility for dental treatment (MacEntee et al., 1999; Paley et al., 2004). Policy decisions about mouthcare rendered to frail elders are made usually by physicians and nurses, despite their limited expertise in oral healthcare. Rarely are dentists or dental hygienists part of policy deliberations, either at a local or national level (Fiske et al., 1996; Nitschke, 2001; Department of Health, 2005). Moreover, when oral healthcare guidelines are in place, all too frequently they are overlooked in some jurisdictions (Adams, 1996; Frenkel, 1999; MacEntee et al., 1999), in as much the same way as other “peripheral” services, such as management of pressure sores (Buss et al., 2004), are overlooked.

Organizational structure in nursing homes

Administrators of nursing facilities can feel insecure about monitoring oral health, and seek help from dental professionals as much as possible (MacEntee et al., 1999). However, others do not welcome dental professionals because of the expectations they might bring, or more practically and ethically, because they would abrogate the nurses’ responsibility for daily oral healthcare. Dentists and dental hygienists in contrast have suggested that their participation in interdisciplinary care conferences would be useful to everyone in the nursing facility.

Providing accessible dental services

People are more easily upset physically and emotionally as they grow frail, so routine dentistry should be readily accessible to them without moving to remote dental clinics (MacEntee et al., 1999; Paley et al., 2004). Meals and medications are easily missed when they have to travel afar to a dentist, which is doubly difficult if they are incontinent. Disturbances of dementia are exacerbated by strange people and places. Domiciliary care, therefore, allows continuity of regular treatment even when individuals have significant problems with mobility and health. Nonetheless, there are occasions when it is necessary to transport a frail resident for special care at another clinic or private dental practice.

On-site dentistry with mobile equipment

A dental professional with good mobile dental equipment can serve patients at home or in a facility (Figure 12.2).

Figure 12.2 A portable dental unit with compressor being used by a dentist to treat a patient with multiple sclerosis at home in her own reclining chair.

Access to residents who are bedridden is more difficult and ergonomically demanding, but it certainly is possible (Figure 12.3).

Figure 12.3 Dentistry with portable equipment for a patient who is bedridden.

A typical portable or mobile dental unit will include a reclining chair with headrest, an intense light, high- and low-speed handpieces, air and water syringes with air compressor, and a self-contained high-vacuum suction with vacuum pump, while some come also with a radiographic unit (Figure 12.4).

Figure 12.4 Portable dental unit (Mobile Dental Systems PortOP III Portable Dental Unit, MDSysCo, LLC, Austin, TX).

(Reprinted with permission.)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses