Chapter 12

Chronic Kidney Disease and Dialysis

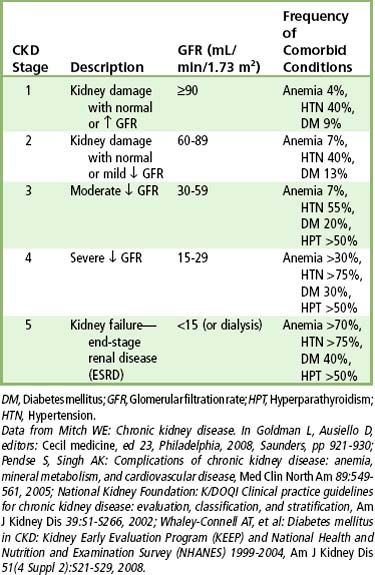

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and its ultimate result, kidney failure, is a worldwide problem that continues to increase in prevalence.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

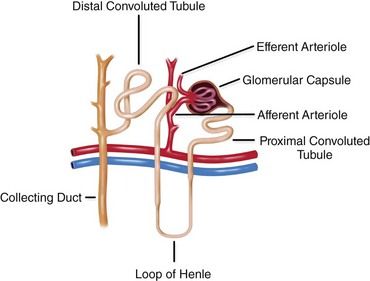

The kidneys have several important functions: They regulate fluid volume and the acid/base balance of plasma; excrete nitrogenous waste; synthesize erythropoietin, 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, and renin; are responsible for drug metabolism; and serve as the target organ for parathormone and aldosterone. Under normal physiologic conditions, 25% of the circulating blood perfuses the kidney each minute. The blood is filtered through a complex series of tubules and glomerular capillaries within the nephron, the functional unit of the kidney (

Definition

CKD is a progressive loss of renal function that persists for 3 months or longer.

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

More than 26 million people (an estimated 11% of the adult population) in the United States have some form of kidney disease.

Etiology

ESRD is caused by conditions that destroy nephrons. The four most common known causes of ESRD are diabetes mellitus (37%), hypertension (24%), chronic glomerulonephritis (16%), and polycystic kidney disease (4.5%). Other common causes, in decreasing order, are systemic lupus erythematosus, neoplasm, urologic disease, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) nephropathy.

Pathophysiology and Complications

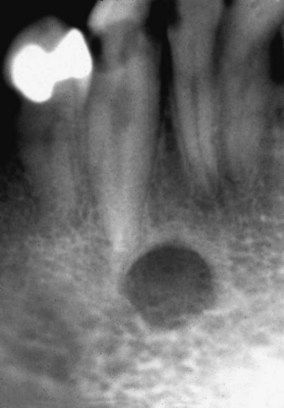

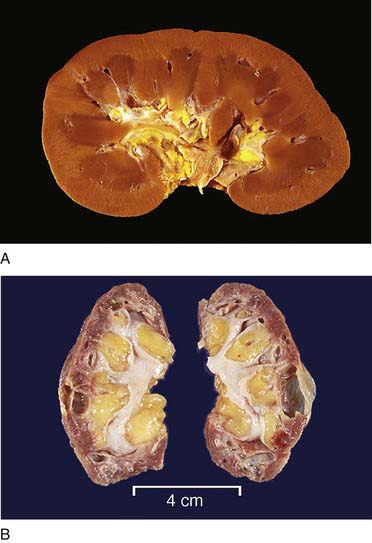

Deterioration and destruction of functioning nephrons are the underlying pathologic processes of renal failure. The nephron includes the glomerulus, tubules, and vasculature. Various diseases affect different segments of the nephron at first, but the entire nephron eventually is affected. For example, hypertension affects the vasculature first, whereas glomerulonephritis affects the glomeruli first. Once lost, nephrons are not replaced. However, because of compensatory hypertrophy of the remaining nephrons, normal renal function is maintained for a time. During this period of relative renal insufficiency, homeostasis is preserved. The patient remains asymptomatic and demonstrates minimal laboratory abnormalities such as a diminished GFR. Normal function is maintained until greater than 50% of nephrons are destroyed. Subsequently, compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed, and the signs and symptoms of uremia appear. In terms of morphology, the end-stage kidney is markedly reduced in size, scarred, and nodular

FIGURE 12-2 Gross renal anatomy. A, A normal kidney. B, Atrophic kidneys from a patient with chronic glomerulonephritis.

(From Klatt EC: Robbins and Cotran atlas of pathology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

A patient in early renal failure may remain asymptomatic, but physiologic changes invariably develop as the disease progresses. Such changes result from the loss of nephrons. Renal tubular malfunction causes the sodium pump to lose its effectiveness, and sodium excretion occurs. Along with sodium, excessive amounts of dilute urine are excreted, which accounts for the polyuria that is commonly encountered.

Patients with advanced renal disease develop uremia, which is uniformly fatal if not treated. Failing kidneys are unable to concentrate and filter the intake of sodium, which contributes to the drop in urine output, development of fluid overload, hypertension, and risk for severe electrolyte disturbances (sodium depletion and hyperkalemia—higher-than-normal levels of potassium) and cardiac disease. These cardiovascular system–related events cause approximately half of the deaths occurring annually among patients with ESRD.

The buildup of nonprotein nitrogen compounds in the blood, mainly urea, as a consequence of loss of glomerular filtration function, is called azotemia. Level of azotemia is measured as blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Acids also accumulate because of tubular impairment. The combination of waste products serves as a substrate for the development of metabolic acidosis, the major result of which is ammonia retention. In the later stages of renal failure, acidosis causes nausea, anorexia, and fatigue. Patients may hyperventilate to compensate for the metabolic acidosis. With acidosis superimposed on ESRD, adaptive mechanisms already are taxed beyond normal levels, and any increase in demand can lead to serious consequences. For example, sepsis or a febrile illness can result in profound acidosis and may be fatal.

Patients with ESRD demonstrate several hematologic abnormalities, including anemia, leukocyte and platelet dysfunction, and coagulopathy. Anemia, caused by decreased erythropoietin production by the kidney, inhibition of red blood cell production and hemolysis, bleeding episodes, and shortened red cell survival, is one of the most familiar manifestations of ESRD. Most of these effects result from unidentified toxic substances in uremic plasma and from other factors.

Hemorrhagic diatheses, characterized by tendency toward abnormal bleeding and bruising, are common in patients with ESRD and are attributed primarily to abnormal platelet aggregation and adhesiveness, decreased platelet factor 3, and impaired prothrombin consumption. Defective platelet production also may play a role. Platelet factor 3 enhances the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin by activated factor X.

The cardiovascular system is affected by athero- and arteriosclerosis and arterial hypertension—the latter due to sodium chloride (NaCl) retention, fluid overload, and inappropriately high renin levels. Congestive heart failure and hypertrophy of the left ventricle, which may compromise coronary artery blood flow, are relatively common developments. These complications, along with electrolyte disturbances, put patients with ESRD at increased risk for sudden death due to myocardial infarction.

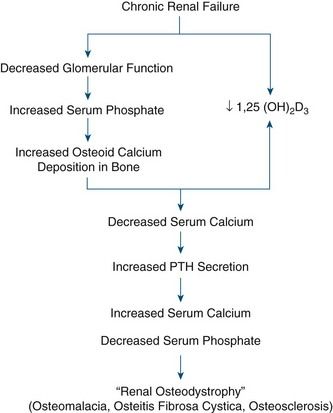

A variety of bone disorders are seen in ESRD; these are collectively referred to as renal osteodystrophy. Decreased kidney function results in decreased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production, which leads to reduced intestinal absorption of calcium (thereby contributing to hypocalcemia). With advanced CKD, renal phosphate excretion drops, and results in increased levels of serum phosphorus. Excess phosphorus causes serum calcium to be deposited in bone (osteoid), leading to a decreased serum calcium level and weak bones. In response to low serum calcium, the parathyroid glands are stimulated to secrete parathormone (PTH). This results in secondary hyperparathyroidism. PTH has three main functions:

• Inhibiting the tubular reabsorption of phosphorus

• Stimulating renal production of the vitamin D necessary for calcium metabolism

High levels of PTH are sustained, however, because in ESRD the failing kidney does not synthesize 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, the active metabolite of vitamin D; thus, calcium absorption in the gut is inhibited. PTH activates tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1, which mediate bone remodeling, calcium mobilization from bones, and increased excretion of phosphorus, potentially leading to formation of renal and metastatic calcifications. Levels of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), a key regulator of phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism, also increase and result in inhibition of osteoblast maturation and matrix mineralization.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical features of renal failure are listed in

Box 12-1 Clinical Features of Chronic Renal Failure

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with CKD may show few clinical signs or symptoms until the condition progresses to stage 3. At this stage and beyond, patients may complain of a general ill feeling, fatigue, headaches, nausea, loss of appetite, and weight loss. With further progression, anemia, leg cramps, insomnia, and nocturia often develop. The anemia produces pallor of the skin and mucous membranes and contributes to the symptoms of lethargy and dizziness. Hyperpigmentation of the skin is characterized by a brownish-yellow appearance caused by the retention of carotene-like pigments normally excreted by the kidney. These pigments also may cause profound pruritus. An occasional finding is a whitish coating on the skin of the trunk and arms produced by residual urea crystals left when perspiration evaporates (“uremic frost”).

Patients with renal failure are more likely to experience bone pain and to develop gastrointestinal signs and symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, generalized gastroenteritis, and peptic ulcer disease. Uremic syndrome commonly causes malnutrition and diarrhea. Patients demonstrate mental slowness or depression and become psychotic in later stages. They also may exhibit signs of peripheral neuropathy and muscular hyperactivity (twitching). Convulsions may be a late manifestation that directly correlates with the degree of azotemia. Additional findings may include stomatitis manifested by oral ulceration and candidiasis (

Because of the bleeding diatheses that accompany ESRD, hemorrhagic episodes are not uncommon, particularly occult gastrointestinal bleeding. In patients who receive dialysis, however, benefits include improved control of uremia and less severe bleeding. Skin manifestations include ecchymoses, petechiae, purpura, and gingival or mucous membrane bleeding (e.g., epistaxis).

Cardiovascular manifestations of ESRD include hypertension, congestive heart failure (shortness of breath, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion, peripheral edema), and pericarditis.

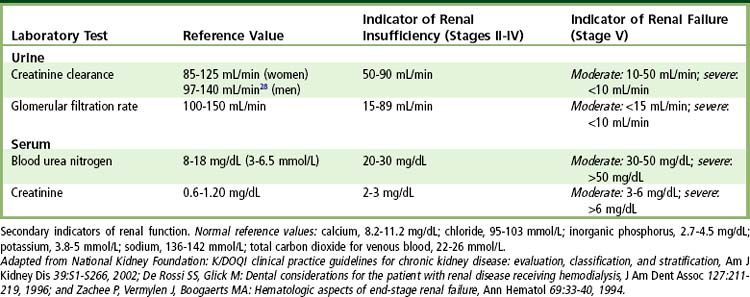

Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis of kidney disease is based on history, physical evidence, laboratory evaluation, and, in select disorders, imaging and biopsy. GFR, urinalysis, BUN, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, electrolyte measurements, and protein electrophoresis are used to monitor disease progress. The most basic test of kidney function is urinalysis, with special emphasis on specific gravity and the presence of protein. The principal marker of kidney damage is persistent protein in the urine, whereas GFR is the best measure of overall kidney function.

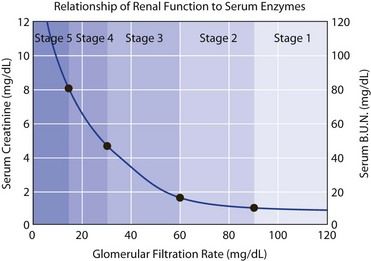

FIGURE 12-6 Relationship of renal function to serum enzymes.

(Courtesy Matt Hazzard, University of Kentucky.)

As renal failure develops, the patient often remains asymptomatic until the GFR drops below 20 mL/minute, the creatinine clearance drops below 20 mL/minute, and the BUN is above 20 mg/dL. In fact, uremic syndrome is rare before the BUN concentration exceeds 60 mg/dL. Other tests used to monitor kidney disease include determinations of serum electrolytes involved in acid-base regulation and calcium and phosphorus metabolism (see

Medical Management

Conservative Care

The National Kidney Foundation published clinical practice guidelines for the management of CKD.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses