Prevention and Management of Extraction Complications

James R. Hupp

This chapter discusses the most common complications, some minor and some more serious, occurring during or after oral surgical procedures. These are surgical, not medical, complications; the latter are discussed in Chapter 3.

Prevention of Complications

As in the case of medical complications, the best and easiest way to manage a surgical complication is to prevent it from ever happening. Prevention of surgical complications is best accomplished by a thorough preoperative assessment and comprehensive treatment plan, followed by careful execution of the surgical procedure. Only when these are routinely performed can the surgeon expect to have few complications. However, even with such planning and the use of excellent surgical techniques, complications still occasionally occur. In situations in which the dentist has planned carefully, the complication is often predictable and can be managed routinely. For example, when extracting a maxillary first premolar that has long, thin roots, it is far easier to remove the buccal root than the palatal root. Therefore, the surgeon uses more force toward the buccal root than toward the palatal root. If a root does fracture, it involves the buccal root rather than the palatal root, since in most cases buccal root retrieval is more straightforward.

Dentists must perform surgery that is within the limits of their capabilities. They must, therefore, carefully evaluate their training and abilities before deciding to perform a specific surgical task. Thus, for example, it is inappropriate for a dentist with limited experience in the management of impacted third molars to undertake the surgical extraction of an embedded tooth. The incidence of operative and postoperative complications is unacceptably high in this situation. Surgeons must be cautious of unwarranted optimism, which clouds their judgment and prevents them from delivering the best possible care to the patient. The dentist must keep in mind that referral to a specialist is an option that should always be exercised if the planned surgery is beyond the dentist’s own skill level. In some situations, this is not only a moral obligation but also wise medicolegal risk management and provides peace of mind.

In planning a surgical procedure, the first step is always a thorough review of the patient’s medical history. Several of the complications to be discussed in this chapter can be caused by inadequate attention to medical histories that would have revealed the presence of a factor that would increase surgical risk.

One of the primary ways to prevent complications is by obtaining adequate images and carefully reviewing them (see Chapter 7). Radiographs must include the entire area of surgery, including the apices of the roots of the teeth to be extracted as well as local and regional anatomic structures such as the adjacent parts of the maxillary sinus or the inferior alveolar canal. The surgeon should look for the presence of abnormal tooth root morphology or signs that the tooth may be ankylosed. After careful examination of the radiographs, the surgeon may need to alter the treatment plan to prevent or limit the magnitude of the complications that might be anticipated with a closed extraction. Instead, the surgeon should consider surgical approaches to removing teeth in such cases.

After an adequate medical history has been taken and the radiographs have been analyzed, the surgeon goes on to preoperative planning. This is not simply a preparation of a detailed surgical plan and needed instrumentation but is also a plan for managing patient pain and anxiety and postoperative recovery (instructions and modifications of normal activity for the patient). Thorough preoperative instructions and explanations for the patient are essential in preventing or limiting the impact of the majority of complications that occur in the postoperative period. If the instructions are not carefully explained and the importance of compliance made clear, the patient is less likely to comply with them.

Finally, to keep complications at a minimum, the surgeon must always follow basic surgical principles. There should be clear visualization and access to the operative field, which requires adequate light, adequate soft tissue retraction and reflection (including lips, cheeks, tongue, and soft tissue flaps), and adequate suction. The teeth to be removed must have an unimpeded pathway for removal. Occasionally, bone must be removed and teeth sectioned to achieve this goal. Controlled force is of paramount importance; this means “finesse,” not “force.” The surgeon must follow the principles of asepsis, atraumatic handling of tissues, hemostasis, and thorough débridement of the wound after the surgical procedure. Violation of these principles leads to an increased incidence and severity of surgical complications.

Soft Tissue Injuries

Injuries to the soft tissue of the oral cavity are almost always the result of the surgeon’s lack of adequate attention to the delicate nature of the mucosa, attempts to do surgery with inadequate access, rushing during surgery, or the use of excessive and uncontrolled force. The surgeon must continue to pay careful attention to soft tissue while working on bone and tooth structures (Box 11-1).

Tear of a Mucosal Flap

The most common soft tissue injury during oral surgery is the tearing of the mucosal flap during surgical extraction of a tooth. This usually results from an initially inadequately sized envelope flap, which is then forcibly retracted beyond the ability of the tissue to stretch as the surgeon tries to gain needed surgical access (Figure 11-1). This results in a tearing, usually at one end of the incision. Prevention of this complication is threefold: (1) creating adequately sized flaps to prevent excess tension on the flap, (2) using controlled amounts of retraction force on the flap, and (3) creating releasing incisions, when indicated. If a tear does occur in the flap, the flap should be carefully repositioned once the surgery is completed. If the surgeon or assistant sees a flap beginning to tear, the hard tissue surgery should be stopped for lengthening the incision to gain better access or to create a releasing incision. In most patients, careful suturing of the tear results in adequate, but somewhat delayed, healing. If the tear is especially jagged, the surgeon may consider excising the edges of the torn flap to create a smooth flap margin before closure. This latter step should be performed with caution because excision of excessive amounts of tissue leads to closure of the wound under tension and probable wound dehiscence, or it might compromise the amount of attached gingiva adjacent to a tooth.

Puncture Wound

The second soft tissue injury that occurs with some frequency is inadvertent puncturing of soft tissue. Instruments such as a straight elevator or a periosteal elevator may slip from the surgical field and puncture or tear into adjacent soft tissue.

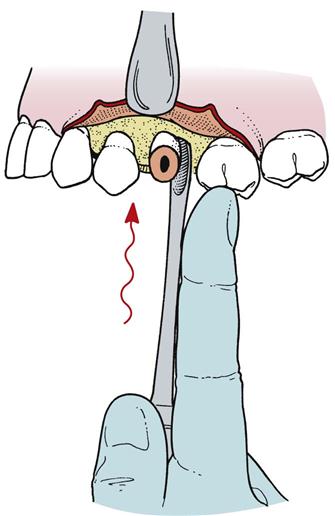

Once again, this injury is the result of using uncontrolled force and is best prevented by the use of controlled force, with special attention given to using finger rests or support from the opposite hand if slippage is anticipated. If the instrument slips from the tooth or bone, the surgeon’s fingers can catch the operating hand before injury occurs (Figure 11-2). If a puncture wound does occur in the mucosa, the ensuing treatment is primarily aimed at preventing infection and allowing healing to occur, usually by secondary intention. If the wound bleeds excessively, it should be controlled by direct pressure applied to the wound. Once hemostasis is achieved, the wound is usually left open unsutured; thus, even if a small infection were to occur, there is an adequate pathway for drainage.

Stretch or Abrasion

Abrasions or burns to lips, corners of the mouth, or flaps usually result from the rotating shank of the bur rubbing on soft tissue or from a metal retractor coming in contact with soft tissue (Figure 11-3). When the surgeon is focused on the cutting end of the bur, the assistant should be aware of the location of the shank of the bur in relation to the patient’s cheeks and lips. However, the surgeon should also remain aware of the shaft’s location. If an area of oral mucosa is abraded or burned, little treatment is possible other than keeping the area clean with regular oral rinsing. Usually, such wounds heal in 4 to 7 days (depending on the depth of damage) without scarring. If such an abrasion or burn does develop on skin, the dentist should advise the patient to keep it covered with an antibiotic ointment. The patient must apply the ointment only on the abraded area and not spread it onto intact skin because the ointment may cause ulceration or a rash. These abrasions usually take 5 to 10 days to heal. The patient should keep the area moist with small amounts of ointment during the entire healing period to prevent eschar formation and delayed healing as well as to keep the area reasonably comfortable. Scarring or permanent discoloration of the affected skin may occur but is usually prevented with proper wound care.

Problems with a Tooth Being Extracted

Root Fracture

The most common problem associated with the tooth being extracted is fracture of its roots. Long, curved, divergent roots that lie in dense bone are the most likely to be fractured. The main methods of preventing fracture of roots is to perform surgery in the manner described in previous chapters or to use an open extraction technique and remove bone to decrease the amount of force necessary to remove the tooth (Box 11-2). Recovery of a fractured root with a surgical approach is discussed in Chapter 8.

Root Displacement

The tooth root that is most commonly displaced into unfavorable anatomic spaces is the maxillary molar root, when it is forced or lost into the maxillary sinus. If a fractured root of a maxillary molar is being removed with a straight elevator that is being used with excessive apical pressure, the root can be displaced into the maxillary sinus. If this occurs, the surgeon must make several assessments to determine the appropriate treatment. First, the surgeon must identify the size of the root lost into the sinus. It may be a root tip of several millimeters (mm) or an entire tooth root. The surgeon must next assess whether there has been any infection of the tooth or periapical tissues. If the tooth was not infected, management is more straightforward than if the tooth had been acutely infected. Finally, the surgeon must assess the preoperative condition of the maxillary sinus. For the patient who has a healthy maxillary sinus, it is easier to manage a displaced root than if the sinus is or has been chronically infected.

If the displaced tooth fragment is a small (2 or 3 mm) root tip, and the tooth and sinus have no pre-existing infection, the surgeon should make a brief attempt at removing the root. First, a radiograph of the fractured tooth root should be taken to document its position and size. Once that has been accomplished, the surgeon should irrigate through the small opening in the socket apex and then suction the irrigating solution from the sinus via the socket. This occasionally flushes the root apex from the sinus through the socket. The surgeon should check the suction solution and confirm radiographically that the root has been removed. If this technique is not successful, no additional surgical procedure should be performed through the socket, and the root tip should be left in the sinus. The small, noninfected root tip can be left in place because it is unlikely to cause any troublesome sequelae. Additional surgery in this situation causes more patient morbidity than leaving the root tip in the sinus. If the root tip is left in the sinus, the surgeon should take measures similar to those taken when leaving any root tip in place. The patient must be informed of the decision and given proper follow-up instructions for regular monitoring of the root and the sinus.

The oroantral communication should be managed as discussed later, with a “figure-of-eight” suture over the socket, sinus precautions, antibiotics, and a nasal spray to lessen the chance of infection by keeping the ostium open. The most likely occurrence is that the root apex will fibrose onto the sinus membrane with no subsequent problems. If the tooth root is infected or the patient has chronic sinusitis, the patient should be referred to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon for removal of the root tip via a Caldwell-Luc or endoscopic approach.

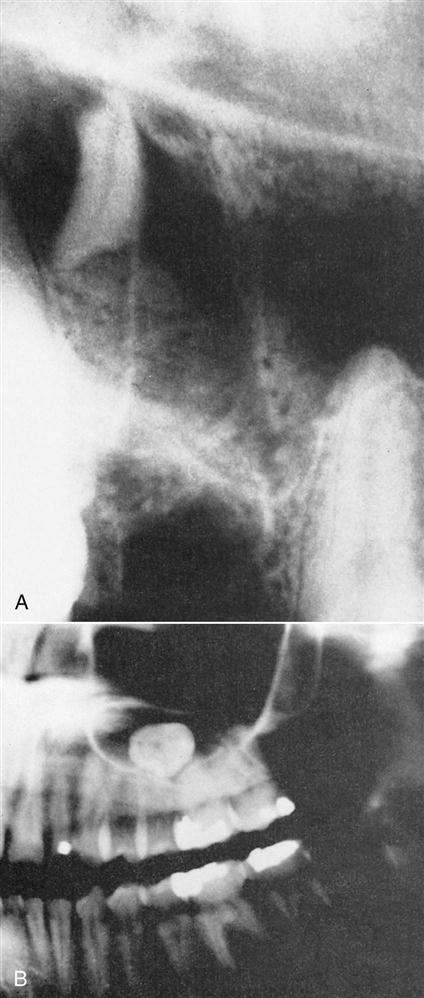

If a large root fragment or the entire tooth is displaced into the maxillary sinus, it should be removed (Figure 11-4). The usual method is a Caldwell-Luc approach into the maxillary sinus in the canine fossa region, followed by removal of the tooth. This procedure should be performed by oral-maxillofacial surgeons (see Chapter 20).

Impacted maxillary third molars are occasionally displaced into the maxillary sinus (from which they are removed via a Caldwell-Luc approach). But if displacement occurs, it is more commonly into the infratemporal space. During elevation of the tooth, the elevator may force the tooth posteriorly through the periosteum into the infratemporal fossa. The tooth is usually lateral to the lateral pterygoid plate and inferior to the lateral pterygoid muscle. If good access and light are available, the surgeon should make a single cautious effort to retrieve the tooth with a hemostat. However, the tooth is usually not visible, and blind probing results in further displacement. If the tooth is not retrieved after a single effort, the incision should be closed and the operation stopped. The patient should be informed that the tooth has been displaced and will be removed later. Antibiotics should be given to help decrease the possibility of an infection, and routine postoperative care should be provided. During the initial healing time, fibrosis occurs and stabilizes the tooth in a firm position. The tooth is removed later by an oral-maxillofacial surgeon after radiographic localization.

Lingual cortical bone over the roots of the molars becomes thinner as it progresses posteriorly. Mandibular third molars, for example, frequently have dehiscence in overlying lingual bone and may be actually sitting in the submandibular space preoperatively. Fractured mandibular molar roots that are being removed with apical pressures may be displaced through the lingual cortical plate and into the submandibular space. Even small amounts of apical pressure can result in displacement of the root into that space. Prevention of displacement into the submandibular space is primarily achieved by avoiding all apical pressures when removing mandibular roots.

Triangular-shaped elevators such as the Cryer elevator are usually used to elevate broken tooth roots of mandibular molars. If the root disappears during root removal, the dentist should make a single effort to remove it. The index finger of the left hand is inserted onto the lingual aspect of the floor of the mouth in an attempt to place pressure against the lingual aspect of the mandible and force the root back into the socket. If this works, the surgeon may be able to tease the root out of the socket with a root-tip pick. If this effort is not successful at the initial attempt, the dentist should abandon the procedure and refer the patient to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon. The usual, definitive procedure for removing such a root tip is to reflect a soft tissue flap on the lingual aspect of the mandible and gently dissect the overlying mucoperiosteum until the root tip can be found. As with teeth that are displaced into the maxillary sinus, if the root fragment is small and was not infected preoperatively, the oral-maxillofacial surgeon may elect to leave the root in its position because surgical retrieval of the root may be an extensive procedure or risk serious injury to the lingual nerve.

Tooth Lost into the Pharynx

Occasionally, the crown of a tooth or an entire tooth might be lost into the pharynx. If this occurs, the patient should be turned toward the surgeon and placed into a position with the mouth facing the floor as much as possible. The patient should be encouraged to cough and spit the tooth out onto the floor. The suction device can sometimes be used to help remove the tooth.

In spite of these efforts, the tooth may be swallowed or aspirated. If the patient has no coughing or respiratory distress, it is most likely that the tooth was swallowed and has traveled down the esophagus into the stomach. However, if the patient has a violent episode of coughing or shortness of breath, the tooth may have been aspirated through the vocal cords into the trachea and from there on to a mainstem bronchus.

In either case, the patient should be transported to an emergency room, and chest and abdominal radiographs should be taken to determine the specific location of the tooth. If the tooth has been aspirated, consultation with regard to the possibility of removing the tooth with a bronchoscope should be requested. The urgent management of aspiration is to maintain the patient’s airway and breathing. Supplemental oxygen may be appropriate if signs of respiratory distress are observed.

If the tooth has been swallowed, it is highly probable that it will pass through the gastrointestinal tract within 2 to 4 days. Because teeth are not usually jagged or sharp, unimpeded passage occurs in almost all situations. However, it may be prudent to have the patient go to an emergency room and have a radiograph of the abdomen taken to confirm that the tooth is, indeed, in the gastrointestinal tract and not in the respiratory tract. Follow-up radiographs are probably not necessary because swallowed teeth are ultimately passed out along with feces.

Injuries to Adjacent Teeth

When the dentist extracts a tooth, the focus of attention is on that particular tooth and the application of forces to luxate and deliver it. When the surgeon’s total attention is completely focused on this, the likelihood of injury to the adjacent teeth increases. Injury is often caused by the use of a bur to remove bone or divide a tooth for removal. The surgeon should take care to avoid getting too close to adjacent teeth when surgically removing a tooth. This usually requires the surgeon to keep some of the focus on structures adjacent to the site of the surgery.

Fracture or Dislodgment of an Adjacent Restoration

The most common injury to adjacent teeth is the inadvertent fracture or dislodgment of a restoration or damage to a severely carious tooth while the surgeon is attempting to elevate the tooth to be removed (Figure 11-5). If a large restoration exists, the surgeon should warn the patient preoperatively about the possibility of fracturing or displacing it during the extraction. Prevention of such a fracture or displacement is primarily achieved by avoiding application of instrumentation and force on the restoration (Box 11-3). This means that the straight elevator should be used with great caution, being inserted entirely into the periodontal ligament space, or not used at all to luxate the tooth before extraction when the adjacent tooth has a large restoration. If a restoration is dislodged or fractured, the surgeon should make sure that the displaced restoration is removed from the mouth and does not fall into the empty tooth socket. Once the surgical procedure has been completed, the injured tooth should be treated by replacement of the displaced crown or placement of a temporary restoration. The patient should be informed if a fracture of a tooth or restoration has occurred and that a replacement restoration is needed (see Chapter 12).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses