Chapter 11

OCCLUSAL ADJUSTMENT AND EQUILIBRATION

Occlusal Adjustment and Occlusal Equilibration

Occlusal adjustment is the alteration of the occlusal surfaces of teeth by the dentist to change the relationship of occlusal contacts. Although often used synonymously, it should be differentiated from occlusal equilibration, which is the planned alteration of occlusal surfaces to provide stable jaw relationships with stable simultaneous multiple interocclusal contacts and smooth excursive movements, unimpeded by occlusal interferences.

Equilibration is usually carried out in two stages, the first being the alteration of occlusal contacts, and the second the provision of stability. Occlusal adjustment is often easy (to alter the occlusion), but it is difficult to provide the stable interocclusal and jaw to jaw relationships subsequently.

Localized occlusal adjustment is often necessary for re-restoration in a conformative manner (Chapter 12). Adjustment can range from modification of a single tooth to modification of all the teeth. When the entire dentition is adjusted, the ultimate aim is occlusal equilibration. Occlusal equilibration is often required as a prelude to re-restoration in a reorganized approach (Chapter 13).

Restorative indications for occlusal adjustment and equilibration will be considered in detail in the sections on the conformative and reorganized approaches to restorations, Chapters 12 and 13.

Indications for Occlusal Adjustment/Equilibration

- To eliminate plunger cusps.

- To reduce mobility that is bothering the patient – assuming this is possible via adjustment.

- To reduce the load on a restoratively compromised tooth, for example, a guidance tooth such as a canine with an inadequate post, or a premolar with an MOD restoration or a heavily restored tooth with a non-working side contact.

- When there is drifting of the upper anterior teeth. To stabilize the mandibulo/maxillary relationship so eliminating an anterior slide with impingment of the lower incisors on the palatal surfaces of the upper teeth.

- To remove dysfunctional activity of the masticatory muscles before extensive restoration.

- To produce stable jaw relationships prior to extensive re-restoration. This is a primary indication for adjustment/equilibration.

- In the treatment of facial arthromyalgia (TMD). There is no published controlled evidence that adjustment of the occlusion will alleviate the symptoms of facial arthromyalgia more effectively than placebo (mock) adjustment (Chapters 26 and 27). This is not an indication for occlusal adjustment.

- In the treatment of periodontitis. Pihlstrom et al. (1986)1 and Gilmore (1970)2 found no greater attachment loss on teeth with occlusal interferences or deflective contacts than those without such contacts. Following the removal of inflammation, occlusal adjustment can reduce mobility but not always eliminate it,3 splinting may be required. Burgett F. et al., (1992) have reported a statistically significant gain in attachment levels in a group of 22 patients when occlusal equilibration was combined with surgical therapy, oral hygiene instruction, Widman flap or scaling and root planing, as compared to a group of 28 patients treated in a similar fashion but excluding the equilibration.4 It should be noted, however, that over a two-year period, the mean gain in attachment in the equilibrated group was 0.42 mm (S D 0.67) and in the non-equilibrated group, 0.02 mm (S D 0.53). Whether these differences are clinically significant is debatable. Furthermore, the equilibrated group received more care and attention therefore confounding the result.

Equilibration for periodontal reasons in a large horizontal : vertical ratio case is not recommended because of the risk of eliminating anterior guidance and rendering the patient uncomfortable. In the large vertical : horizontal case it could be justified, but only if there are other cogent reasons for doing so, for example, drifting anterior teeth. The role of trauma from occlusion on the progression of periodontitis is still unresolved and is well referenced by Burgett et al. (1992).4 There is no controlled published evidence confirming that trauma from occlusion precipitates or potentiates periodontitis in humans. How well, induced lesions in experimental animal models represent the site and time-specific lesions in humans, still requires clarification.

Prophylactic occlusal adjustment/equilibration to prevent periodontitis cannot be recommended. Adjustment/equilibration to reduce tooth mobility that concerns a patient can be justified provided that the periodontitis is treated.

Considerations

Intercuspal Position

In its simplest form, occlusal adjustment consists, of altering the occlusal surfaces of teeth in the intercuspal position (IP).

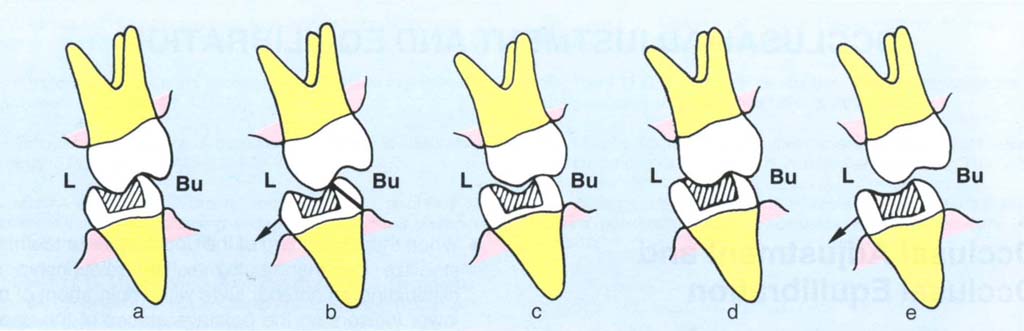

In Figure 11-1, the palatal cusp of 27 has overerupted into the scooped out restoration of 37. In the right lateral excursion (Figs 11-1b+c), the over-erupted palatal cusp of 27 formed a non-working side contact against the buccal wall of 37. Replacement of the restoration in 37 should be preceded by shortening of the palatal cusp of 27 (Figs 11-1d+e) so enabling restoration to the correct occlusal form. In lateral excursion, the palatal cusp of 27 will now be clear of the buccal cusp of 37, reducing the risk of fracture. Such an adjustment is in the intercuspal position, although lateral excursions are obviously observed.

Fig. 11-1 Occlusal adjustment. (Many of the diagrams are based on those presented by Dawson, 1974; Wise, 1986.;

Fig. 11-1a Buccolingual diagram (BU = buccal, L = lingual) through 27, 37. The palatal cusp of 27 has overerupted into the scooped out restoration of 37.

Fig. 11-1b The palatal cusp of 27 and the buccal cusp of 37 form a non-working side contact in right lateral excursion leading to the fracture of the 37 buccal wall.

Fig. 11-1c Prior to restoration of 37 the palatal cusp of 27 should be reshaped by shortening the cusp.

Fig. 11 -1d The fossa of the restoration is built up so as to contact the opposing cusp in the IP.

Fig. 11-1e In right lateral excursion the anterior guidance separates the now shorter palatal cusp of 27 from 37 yet a stabilizing contact remains in the IP.

The presence of a plunger cusp requires occlusal adjustment in order to prevent food packing. Wherever possible, the cusp should be reshaped to provide contact with an opposing fossa, thereby reducing the chances of food packing.

Centric Relation Contact Position (CRCP)

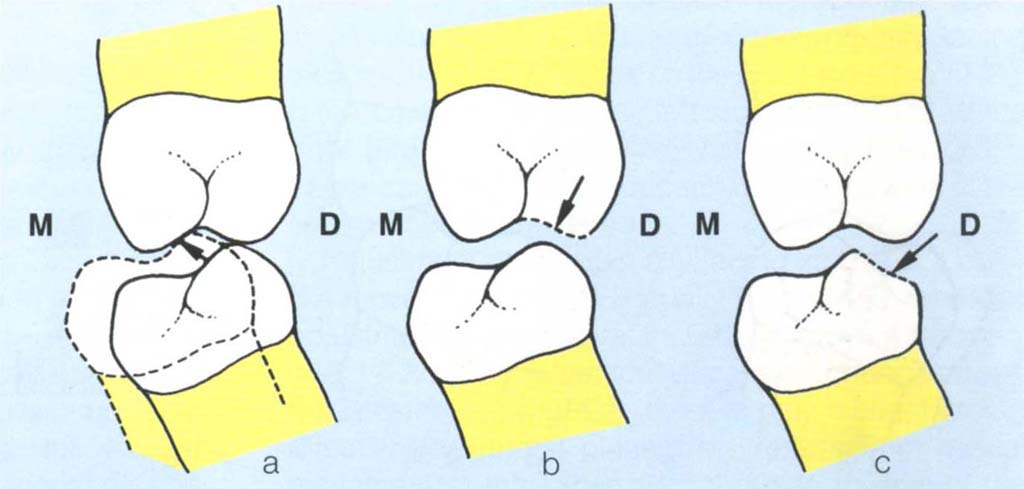

It is possible to adjust the cuspal inclines in the CRCP so that when the masticatory muscles contract there is neither an anterior component of force directing the mandible forwards into the intercuspal position, nor a lateral component directing it sideways (Figs 11-2a–c).

Fig. 11-2a to c Sagittal plane diagram (M = mesial, D = distal) for example, between the distobuccal cusp of tilted 36 and distopalatal cusp of 26. (a) Contact in the CRCP-solid outline. If the patient squeezes, the mandible is forced forwards by the action of the cusp inclines, resulting in the IP (dashed); (b) Adjustment of the upper cusps can eliminate the inclined plane action (arrow to broken line) and/or (c) Adjustment of the lower cusp can eliminate the inclined plane action (arrow to broken line).

The Saggital Plane

Large Vertical: Horizontal Ratio between CRCP and IP

It can be see from Figs 11-2d+e that as the vertical dimension is reduced in the CRCP, there is an apparent anterior movement of the mandible, due to the arcing effect around an axis at the condylar level. As the vertical dimension in the CRCP approaches that of the IP this effect results in the two positions becoming progressively closer, so that at the vertical dimension of the IP or at a very slightly closed vertical dimension, the two positions become almost coincident. There is little adaptation required after this type of adjustment, so the result is controlled, predictable and stable.

Fig. 11-2d and e Sagittal plane diagrams (M = mesial, D = distal); (d) large vertical with small horizontal dimension between CRCP (solid) and IP (broken); (e) removal of deflective contacts (broken line) leading to altered vertical dimension in the CRCP with arcing of the mandible. CRCP and original IP are almost coincident.

Fig. 11-2f If the mesial incline is removed (shaded) the cusp tip is moved distally, if the distal incline is removed the cusp tip moves mesially (M = mesial; D = distal).

Reduction of the distal incline of a mandibular cusp moves the cusp tip mesially. And conversely, if the mesial incline is reduced, the cusp tip moves distally (Fig 11-2f). As the vertical dimension is reduced in the CRCP, the mandibular cusp tips will move mesially due to arcing around the horizontal axis of rotation. If the distal cuspal incline is reduced, the cusp tip will move even further mesially. If the mesial incline is reshaped, the mesial movement of the cusp tip due to reduction of vertical dimension can be lessened or eliminated and even sometimes reversed. By employing these concepts, it is often possible to shape cusps, not only to remove deflective contacts, but also to determine the ultimate cusp to opposing tooth relationship.

Shaping of the distal incline of a maxillary cusp moves the cusp tip mesially, whereas shaping of the mesial incline moves it distally. With the reduction of the vertical dimension in CRCP, the maxillary cusps move distally relative to the lower tooth. Reshaping of the appropriate cuspal inclines will control the relationship of the maxillary cusps to the mandibular occlusal surfaces.

It must be emphasized that for this CRCP-IP discrepancy there is little difference between the two positions at the end of occlusal equilibration.5–8

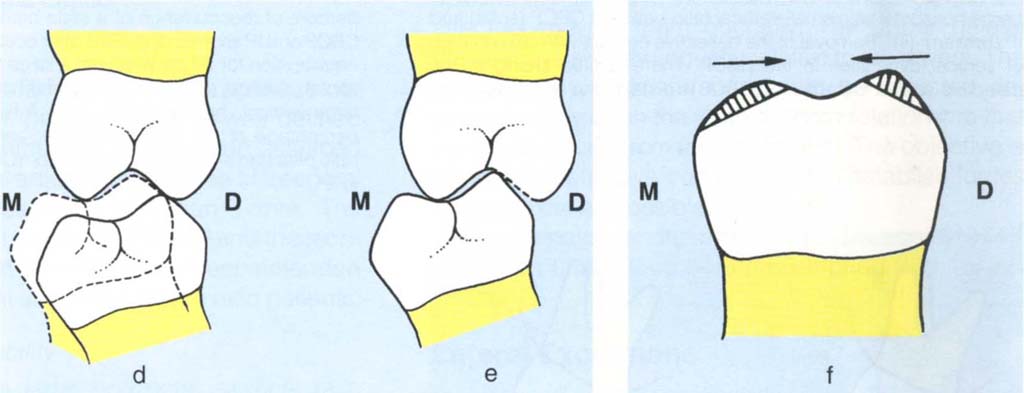

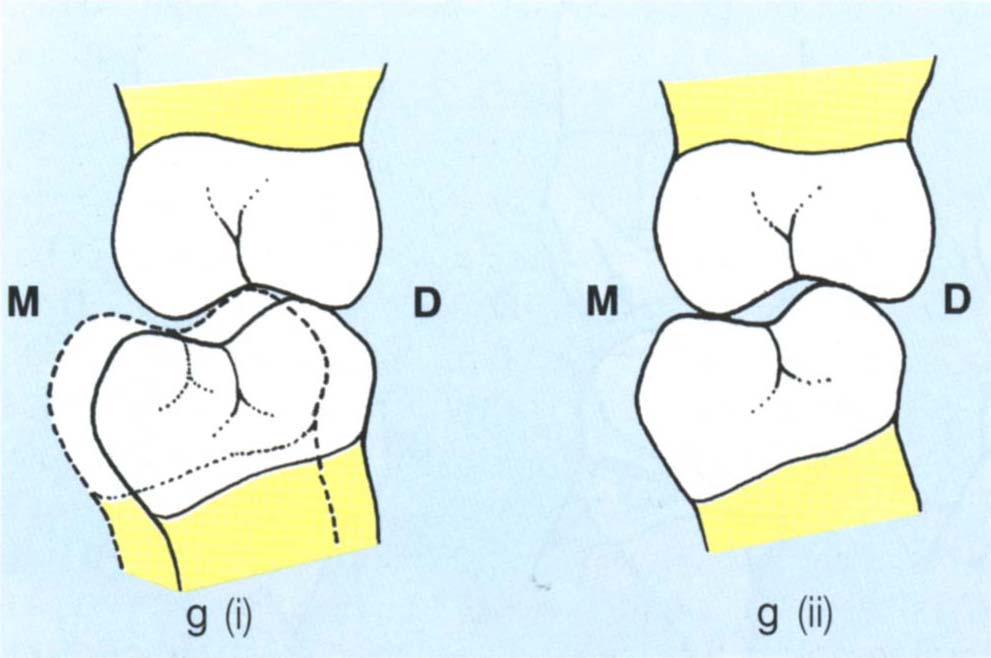

Large Horizontal : Vertical Ratio between CRCP and IP

In the presence of a small vertical component to the CRCP-IP discrepancy, there will be very little arcing effect when deflective contacts are removed. Furthermore, following adjustments in the CRCP, the mandible will frequently reposition itself distally to the original intercuspal position. This results in a large horizontal table between the CRCP and the original IP, that is, ‘an area of freedom in centric’ (Fig 11-2g), with the result that previously contacting anterior teeth may no longer contact, thereby removing anterior guidance and creating rubbing contacts on posterior teeth with associated squeaking sounds. Accommodation to such an ‘area of freedom’ may be difficult, particularly if it is greater than 1 mm and the patient is anxious, occlusally aware and feels stressed. The results of occlusal adjustment for a patient with a large horizontal : vertical ratio are unpredictable and adjustment should only be prescribed with extreme caution.

Fig. 11-2g Sagittal plane diagram (M = mesial, D = distal); (i) Large horizontal with small vertical ratio between CRCP (solid) and IP (broken); (ii) Removal of the deflective contact with little change of vertical dimension in the CRCP. There is little arcing of the mandible so that the adjusted CRCP is distal to the original IP.

Intermediate Group

Some patients do not fit readily into the previous categories. However, in the absence of a well defined large vertical : horizontal ratio, it should be assumed that following occlusal adjustment ‘an area of freedom’ will remain, often measuring less than 1 mm. The principles described by Dawson (1974)6 and the technique of Ramfjord and Ash (1983)8 are recommended for the large horizontal and intermediate ratio patients.

Post Equilibration Stability

Thirty patients with a large horizontal : vertical ratio between CRCP and IP and 30 patients with a large vertical : horizontal ratio were assessed for the presence of a slide six and 12 months after occlusal equilibration in my practice. Although the adjustments had been previously performed by myself, the patient’s notes were not checked prior assessment, so that it was not known which type of ratio applied to the patient under examination. Furthermore, all patients were of a periodontitis resistant type, so that tooth movement should not have occured. Figure 11-2h shows the results. Approximately 10% of the large vertical : horizontal ratio patients re-established a slide after six to 12 months, against 40% of the large horizontal : vertical ratio patients. This suggests that patients with a large vertical : horizontal ratio are more stable following occlusal adjustment and are, therefore, less likely to re-establish/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses