Mental health

Key Points

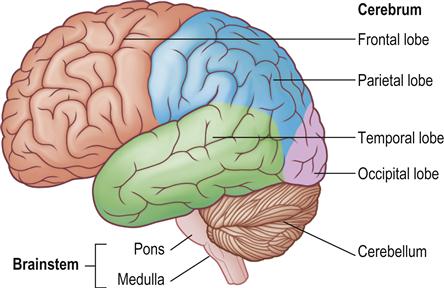

Mental health problems include mental illness; medically unexplained symptoms (MUS – formerly termed psychogenic problems); dementia, discussed in Chapter 13; and learning impairment, discussed in Chapter 28. The brain is a highly complex organ, the functions of many areas remaining unclear (Fig. 10.1). The rapid and widespread effects of mental reactions and emotions can readily be seen from the vasodilatation with blushing seen in anger, anxiety or embarrassment (Fig. 10.2).

All systems of mental disorders and diagnosis stem from the work of Kraepelin, who claimed that certain groups of symptoms often occur together, thus allowing us to call them diseases or syndromes. He regarded each mental illness as distinct, with its own origins, symptoms, course and outcomes, and identified two major groups:

This helped to establish the organic nature of mental disorders and formed the basis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the official classification system of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD; see below). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) is the most widely accepted up-to-date nomenclature used for the classification of mental disorders. Kraepelin’s classification is also embodied in the Mental Health Act 1983, which contains three major categories of mental disturbances – mental illness, personality disorder and mental impairment.

Most disorders are caused by the interaction of:

Genetics plays a role in shaping our personality and consequently our psychological status. The interactions of genetic and environmental factors are believed to cause a number of mental health problems ranging from autism (Ch. 28) to bipolar disorder.

Life stresses, such as bereavement and divorce, can play a significant role in mental health. Lifestyles can also influence mental health; brisk exercise can, by stimulating release of noradrenaline and endorphins, lift depression and create a sense of euphoria. Sunlight stimulates the pineal gland to release serotonin and melatonin, which influence mood. This is one reason why more people tend to be depressed during the darker winter months – seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

Although mental health and mental illness are related, they represent different psychological states.

Mental health is ‘a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’. Indicators of mental health include the following:

■ Emotional well-being – such as perceived life satisfaction, happiness, cheerfulness, peacefulness.

Good mental health is not just the absence of diagnosable mental health problems but is characterized by the ability to:

■ learn

■ feel, express and manage a range of positive and negative emotions

Mental (psychiatric) illness is defined as ‘collectively all diagnosable mental disorders’ or ‘health conditions that are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behaviour (or some combination thereof) associated with distress and/or impaired functioning’.

Depression is the most common type of mental illness and it has been estimated that depression will soon be the second leading cause of disability throughout the world, trailing only ischaemic heart disease. Evidence has shown that mental disorders, especially depressive disorders, are strongly related to the occurrence, successful treatment and course of many chronic diseases, including diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, asthma, obesity and many risk behaviours for chronic disease, such as physical inactivity, smoking, excessive drinking and insufficient sleep.

When people experience severe and/or enduring mental health problems, they are sometimes described as mentally ill but there is no universally agreed cut-off point at which behaviour becomes abnormal enough to be termed mental illness. In any event, the term can imply that all such problems are caused solely by medical or biological factors, whereas most seem to result from complex interactions of medical, biological, social and/or psychological factors.

Personality disorder is defined as ‘an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviours that deviates markedly from the expectation of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time and leads to distress or impairment’.

Mental health problems traditionally have been classified as organic (identifiable brain disease) or functional (no obvious brain structural abnormality); or as neuroses or psychoses. The term ‘neuroses’ covers those symptoms that can be regarded as severe forms of ‘normal’ emotional experiences, such as depression, anxiety or panic; they are now more often called ‘common mental health problems’ and include anxiety (with insight retained), depression, phobias, and obsessive–compulsive and panic disorders. Psychoses are less common and manifest with symptoms that constitute a severe distortion of a person’s perception of reality with loss of insight; they may include hallucinations such as seeing, hearing, smelling or feeling things that no one else can, and also severe and enduring mental health problems such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder (manic depression).

Several diagnostic and classification frameworks have been developed to help identify mental health problems. As mentioned earlier, the two main ones are the ICD (the current one is version 10 – ICD-10) and the DSM (the latest is version 4 revised – DSM-IV-TR); these classify mental health problems in a series of families or categories (Box 10.1).

Therapies include psychotherapy and various psychoactive medications. Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is an increasingly used short-term, problem-focused psychosocial intervention. Evidence from randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses shows that CBT can be an effective intervention for depression, panic disorder, generalised anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder, and its usefulness in a growing range of other issues such as health anxiety/hypochondriasis, social phobia, schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Most patients are cared for in the community, with rare recourse to ‘sectioning’ (admission to hospital against a patient’s will). In the UK, under the Mental Health Act 1983, intended to help doctors manage patients with a mental disorder, patients can be sectioned or detained against their will and given treatment. The types of defined ‘mental disorder’ include ‘severe mental impairment’, ‘psychopathic disorder’ or ‘mental illness’. Under the Act, patients can be sectioned if they are perceived to be a threat to themselves or others.

A patient can only be sectioned if an approved social worker or a close relative and two doctors believe it is necessary. One of these doctors is usually a psychiatrist, while the other knows the patient well, but in an emergency a single doctor’s recommendation may be sufficient.

If a patient is sectioned as an emergency case, they may then be detained under section 4 of the Mental Health Act for up to 72 hours. If doctors believe that further assessment or treatment is necessary, then the patient can be detained under section 2 of the Act, meaning that they can be admitted to hospital and detained for up to 28 days to undergo a full psychiatric assessment. At the end of the 28-day period, if the medical recommendation is for the patient’s stay in hospital to be extended, section 3 of the Act permits a further 6-month extension. A patient can be discharged from hospital at any time if doctors believe they are no longer a threat to themselves or anyone else.

Legislation

Legislation and policy decisions affect individuals’ rights and, in particular, their entitlement to health-care provision, including oral health care. Legislation in the UK has evolved significantly over recent years to protect the rights of the individual, and a summary is presented below.

Mental Health Acts 1983 and 2007

This Act is primarily concerned with the care and treatment of people with a mental health problem that requires that they be detained or treated in the interests of their own health and safety or with a view to protecting other people. It is now 30 years old and new legislation was passed through parliament in the form of the Mental Health Act 2007.

Mental Capacity Act 2005

This Act is relevant to everyone involved in the care, treatment or support of people aged 16 years and over in England and Wales who lack capacity to make all or some decisions for themselves. It also applies to situations where a person may lack capacity to make a decision at a particular time due to illness, drugs or alcohol. Assessments of capacity should be time- and decision-specific.

The Act clarifies the terms ‘mental capacity’ and ‘lack of mental capacity’, and says that a person is unable to make a particular decision if they cannot do one or more of the following:

■ Understand information given to them

■ Retain that information for long enough to be able to make the decision

The new criminal offence of ill treatment or wilful neglect of people who lack capacity also came into force in 2007. Within the law, ‘helping with personal hygiene’ (including tooth-brushing) attracts protection from liability as long as the individual giving this assistance has complied with the Act by assessing a person’s capacity and acting in their best interests. ‘Best-interest’ decisions made on behalf of people who lack capacity should place the fewest restrictions possible on their basic rights and freedoms.

Further changes within the Act include the introduction of lasting powers of attorney (LPA), which extend to health and welfare decisions. When a health professional has a significant concern relating to decisions about serious medical treatment taken under the authority of an LPA, the case can be referred for adjudication to the Court of Protection, which is ultimately responsible for the proper functioning of the legislation. The Act also created an Office of the Public Guardian, which has responsibility for the registration and supervision of both LPAs and court-appointed deputies. Furthermore, independent mental capacity advocates were introduced to support particularly vulnerable incapacitated adults – most often those who lack any other forms of external support – in making certain decisions.

Dental Aspects

Preventive dentistry is crucial in patients with mental health problems. The individual may neglect oral hygiene, dental appointments and instructions unless a caregiver or family member is also involved. Dental staff must use great tact, patience and a sympathetic, unpatronizing manner in handling patients with mental health problems. To avoid causing adverse drug interactions, special precautions should be taken when administering certain antibiotics, analgesics and sedatives. The treatment should be given in the morning, when cooperation tends to be best, with the usual caretakers present and in a familiar environment, and time must be allowed to explain every procedure before it is carried out. The patient should be treated while sitting upright in the dental chair or slightly reclined, to avoid aspiration and postural hypotension (Ch. 5).

Mental health is often affected by social, psychological, biological, genetic and environmental factors, as well as by changes in the brain neurotransmitters of the central nervous system (CNS) (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1

Main parts and functions of the brain

< ?comst?>

| Main part of brain (see Fig. 10.1) | Neurological functions | Mental and other functions | |

| Supratentorial | Cerebrum | Initiation of movement, coordination of movement, temperature, touch, vision, hearing | Higher functions, memory, judgment, ideas, reasoning, problem-solving, emotions, learning |

| Skilful intellectual tasks (e.g. reading, writing, mathematical calculations) | |||

| Limbic system contains several nuclei of grey matter around the brainstem; it commands certain behaviours necessary for survival, e.g. distinction between agreeable and disagreeable; affective functions are developed, e.g. inducing females to nurse and protect their toddlers, or inducing playful moods. Emotions and feelings, like anger, fright, passion, love, hate, joy and sadness, originate in the limbic system, which is also responsible for aspects of personal identity and important functions related to memory | |||

| Brainstem, including mid-brain, pons and medulla | Movement of eyes and mouth, relaying sensory messages (i.e. heat, pain, loudness), hunger, respiration, consciousness, cardiac function, body temperature, involuntary muscle movements, sneezing, coughing, vomiting, swallowing | Self-preservation. Mechanisms of aggression and repetitive behaviour. Instinctive reactions of the so-called reflex arcs and the commands that allow some involuntary actions and control of visceral functions (cardiac, pulmonary, intestinal, etc.) | |

| Infratentorial | Cerebellum | Coordination of voluntary muscle movements and maintenance of posture, balance, equilibrium | – |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Emotion is not a function of any specific brain area but of a circuit that involves interconnected basic structures: the hypothalamus, the anterior thalamic nucleus, the cingulate gyrus, the hippocampus, the prefrontal area, the parahippocampal gyrus and subcortical groupings like the amygdala, the medial thalamic nucleus, the septal area, the basal nuclei and a few brainstem formations (Table 10.2)

Table 10.2

Main parts and functions of the brain involved with emotion and mood

| Brain area | Emotions/moods |

| Amygdala | Mediates and controls major affective activities like friendship, love and affection, expressions of mood and fear, rage and aggression |

| Cingulate gyrus | Coordinates smells and sights with pleasant memories of previous emotions and participates in the emotional reaction to pain and regulation of aggressive behaviour |

| Hippocampus | Responsible for long-term memory |

| Hypothalamus | Connects with other prosencephalic areas and the mesencephalus. Involved with several vegetative functions and some so-called motivated behaviours, like thermal regulations, sexuality, combativeness, hunger and thirst. Also plays a role in emotion, e.g. pleasure, rage, aversion and laughing |

| Nucleus accumbens | Responsible for pleasurable sensations, some of them similar to orgasm |

| Septal region | Associated with different kinds of pleasant sensations, mainly those related to sexual experiences. Anterior frontal lobe is important in the genesis and expression of affection, joy, sadness, hope or despair, as well as the capacity for concentration, problem-solving and abstraction |

| Thalamus | Associated with emotional reactivity due to connections with other limbic system structures. The medial dorsal nucleus connects with the frontal area and hypothalamus. The anterior nuclei connect with the mammillary bodies and, through them, via the fornix, with the hippocampus and cingulate gyrus |

Biological Aspects

Brain Neurotransmitters

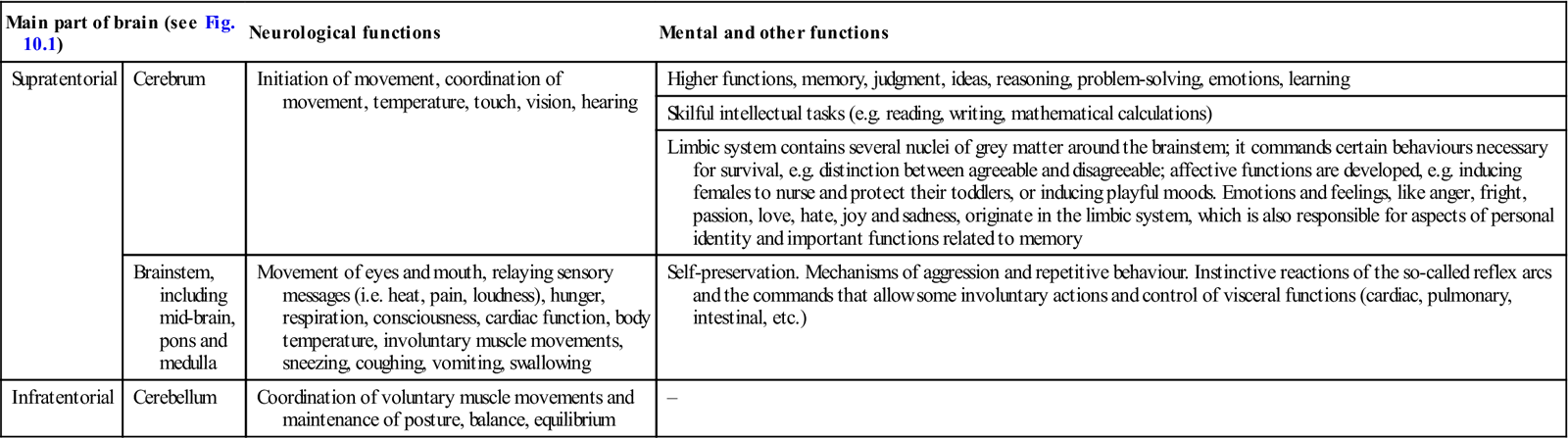

Brain neurotransmitters include monoamines, acetylcholine (ACh), amino acids, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), peptides, substance P and opioids (Table 10.3).

Table 10.3

Some neurotransmitters, with their functions and associated disorders

< ?comst?>

| Neurotransmitter | Functions | Associated disorders |

| Acetylcholine (ACh) | Alertness, memory | Alzheimer disease is associated with 90% loss of ACh in the forebrain and hippocampus |

| Muscle tone, learning, primitive drives, emotions, release of vasopressin (involved in learning and regulation of urine output). ACh-releasing neurons in the pons are active in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (dreaming) | ||

| Relation to sexual performance and arousal – helps control blood flow to genitals, heart rate and blood pressure during sexual intercourse | ||

| Adrenaline (epinephrine) | Physiological expressions of fear and anxiety (fright, fight and flight) | Adrenaline in excess is seen in anxiety disorders |

| Dopamine | Feelings of bliss (‘the pleasure chemical’). More dopamine in the frontal lobe lessens pain and increases pleasure | Parkinson disease is brought on when dopamine fails to reach the basal ganglia |

| Regulation of information flow into the frontal lobe from other areas of brain | Relation to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | |

| Effect on voluntary movement, learning, memory and emotion | Schizophrenia is associated with the inability of dopamine to reach the frontal lobe | |

| Excess dopamine in the limbic system and not enough in the cortex may produce paranoia or inhibit social interaction | ||

| A shortage of dopamine in the frontal lobes may cause poor memory | ||

| Cocaine, opiates and alcohol produce their effects in part via dopamine release | ||

| Endorphins and enkephalins | Involvement in pain reduction, pleasure (enhance release of dopamine) and hibernation, as well as a number of other behaviours | Opiates (natural and synthetic) bind to endorphin and enkephalin brain receptors and alter behaviour |

| Endorphins block pain at receptor sites and facilitate the dopamine pathway that feeds into the frontal lobe, thereby replacing pain with pleasure | ||

| Also produced by the pituitary gland and released as hormones | ||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | Major inhibitory neurotransmitter lessening anxiety. Brain produces substances that enhance anxiety (beta-carbolines), as well as substances that lower anxiety (e.g. allopregnanolone). All modify GABA brain receptors to produce effects | Anxiolytic drugs, such as benzodiazepines, act by enhancing effects of GABA at synapses |

| Glutamate | The main brain excitatory neurotransmitter, with actions mediated at NMDA and AMPA receptors involved in memory formation | Involvement in a ‘suicidal’ response when the brain is damaged, as in stroke. Excess glutamate is neurotoxic and neurons are damaged by the excessive calcium that enters the cell due to glutamate-binding. Glutamate is produced excessively in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Neuropeptide Y/polypeptide YY (NPY/PPYY) | Effect on hypothalamus and stimulation of excessive food intake and fat storage | Link with anxiety and eating disorders |

| Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) | Stimulant to the body and mind. Causes some of the physiological expressions of fear and anxiety (fright, fight and flight response). Modulation of heart rate, blood pressure, learning, memory, waking, emotion | Most forms of depression are associated with a deficiency of noradrenaline |

| High levels can cause aggression | ||

| Stress in children can lead to permanently high levels of noradrenaline, creating the potential for violent behavior | ||

| Raised levels of norepinephrine mixed with dopamine and phenylethylamine produce feelings of infatuation | ||

| Oxytocin | Raised levels give mothers an impulse to cuddle their newborns | High levels contribute to multiple orgasms in women |

| Phenylethylamine | In the limbic system gives feelings of bliss | Low levels in ADHD |

| A natural ingredient in chocolate | ||

| Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) | The ‘feel-good’ hormone that enables relaxation and enjoyment of life | Most forms of depression are associated with a deficiency of serotonin at functionally important serotonergic receptors |

| Synthesized from the amino acid l-tryptophan | ||

| Also a precursor for the pineal hormone melatonin, which regulates the body clock: sleep, appetite, sensory perception, temperature regulation, pain suppression and mood | ||

| Substance P | A neurotransmitter that mediates pain; found throughout the pain pathway | – |

| Release can be blocked by enkephalins and endorphins |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Monoamines include catecholamines (noradrenaline [norepinephrine], adrenaline [epinephrine] and dopamine), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) and histamine. Noradrenaline is released by post-ganglionic neurons of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. ACh mediates transmission at brain synapses involved in the acquisition of short-term memory. Amino acids such as glutamic acid (Glu) are involved in transmission at excitatory synapses and are essential for long-term potentiation (LTP), a form of memory. GABA is released at inhibitory synapses to hyperpolarize the post-synaptic membrane, resulting in an inhibitory post-synaptic potential (IPSP). Peptides not only serve as brain neurotransmitters but some are also hormones; these include vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone; ADH), oxytocin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), angiotensin II and cholecystokinin (CCK). Other transmitters include substance P, which transmits pain impulses and opioids – a term used for all enkephalins, endorphins and morphine-like peptide chemicals, including dynorphin.

Enkephalins (from the Greek kephale, meaning head) are pentapeptides. One enkephalin, leu-enkephalin, terminates in a leucine; the other, met-enkephalin, terminates in a methionine. Enkephalins are released at synapses on neurons involved in transmitting pain signals to the brain and act as an intrinsic pain-suppressing system, hyperpolarizing the post-synaptic membrane and thus inhibiting pain signals.

Endorphins are small-chain peptides that activate opiate receptors, producing feelings of well-being, as well as tolerance to pain. These compounds are hundreds or even thousands of times more potent than morphine. Four groups of endorphins – alpha, beta, gamma and sigma – have been identified.

Dynorphins are other brain opioid peptides.

Factors that influence the production of enkephalins, endorphins and dynorphins include prolonged strenuous activity, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture and placebos. Enkephalins and endorphins bind to neuroreceptors in the brain to give relief from pain. This effect appears to be responsible for the so-called ‘runner’s high’, the temporary loss of pain after severe injury, and the analgesic effects that acupuncture and chiropractic adjustments of the spine can offer.

Enkephalins are found especially in the thalamus and in parts of the spinal cord that transmit pain impulses, and in the adrenal medulla. They act as analgesics and sedatives, and appear to affect mood and motivation. Blood levels rise after exercise and sexual activity, and may explain how a severely wounded person can continue to function. Endorphins may act to prevent the release of substance P, which may account for the sedating effects of endogenous endorphins and of opioids given therapeutically. Endorphins also have anti-ageing effects by removing superoxide, anti-stress activity, pain-relieving effects and memory-improving activity. Endorphins may link the emotional state of well-being and the health of the immune system.

Once any neurotransmitter has acted, it must be removed from the synaptic cleft, usually by reuptake or breakdown, to prepare the synapse for the arrival of the next action potential. All the neurotransmitters except ACh do this via reuptake. ACh is removed from the synapse by enzymatic breakdown by acetylcholinesterase into inactive fragments.

Other Factors that Affect Mental Health

Neuroimmunological Mechanisms

There appears to be a relationship between mental health and the immune system, which can be either overactive or suppressed, leading to associated diseases. There is growing evidence that such neuroimmunological mechanisms might influence immunological and inflammatory disorders and defence against infection. It has, for example, been suggested that stress might underlie some periodontal and other oral diseases. The major route identified for neuroimmunomodulation is via the neuroendocrine system.

In addition to recognizable neurotransmitters, the nervous system contains significant levels of cytokines and their receptors. Thus the possibility of a two-way exchange of information is clearly present. Immune cells possess a host of receptor profiles for modulatory substances and many of these are common to the nervous system. Two different pathways and effects of immediate stress can be demonstrated:

In severe long-term stress, natural opioids are released; the adrenals release met-enkephalin and the hypothalamus releases beta-endorphin, which leads to enhanced anti-tumour activity of natural killer (NK) cells and proliferative response of lymphocytes.

Inflammatory cytokines – interleukin (IL)-1b, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) – activate the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. IL-1 modulates brain catecholamine activity; depletion of central catecholamines potentiates severity of inflammation and also affects the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). IL-1, IL-6 and nitric oxide modulate brain serotonin activity, depletion of which enhances the inflammatory response.

Under stress conditions, if immune activity is not controlled, it may reach a state of activation in which host injury and tissue destruction can take place (autoimmunity).

Anxiety and Stress

Anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive and unrealistic worry about everyday tasks or events, or may be specific to certain objects or rituals. Stress keeps people alert and ready to avoid danger, but when it persists, illness can result.

Anxiety Disorders

Clinical features

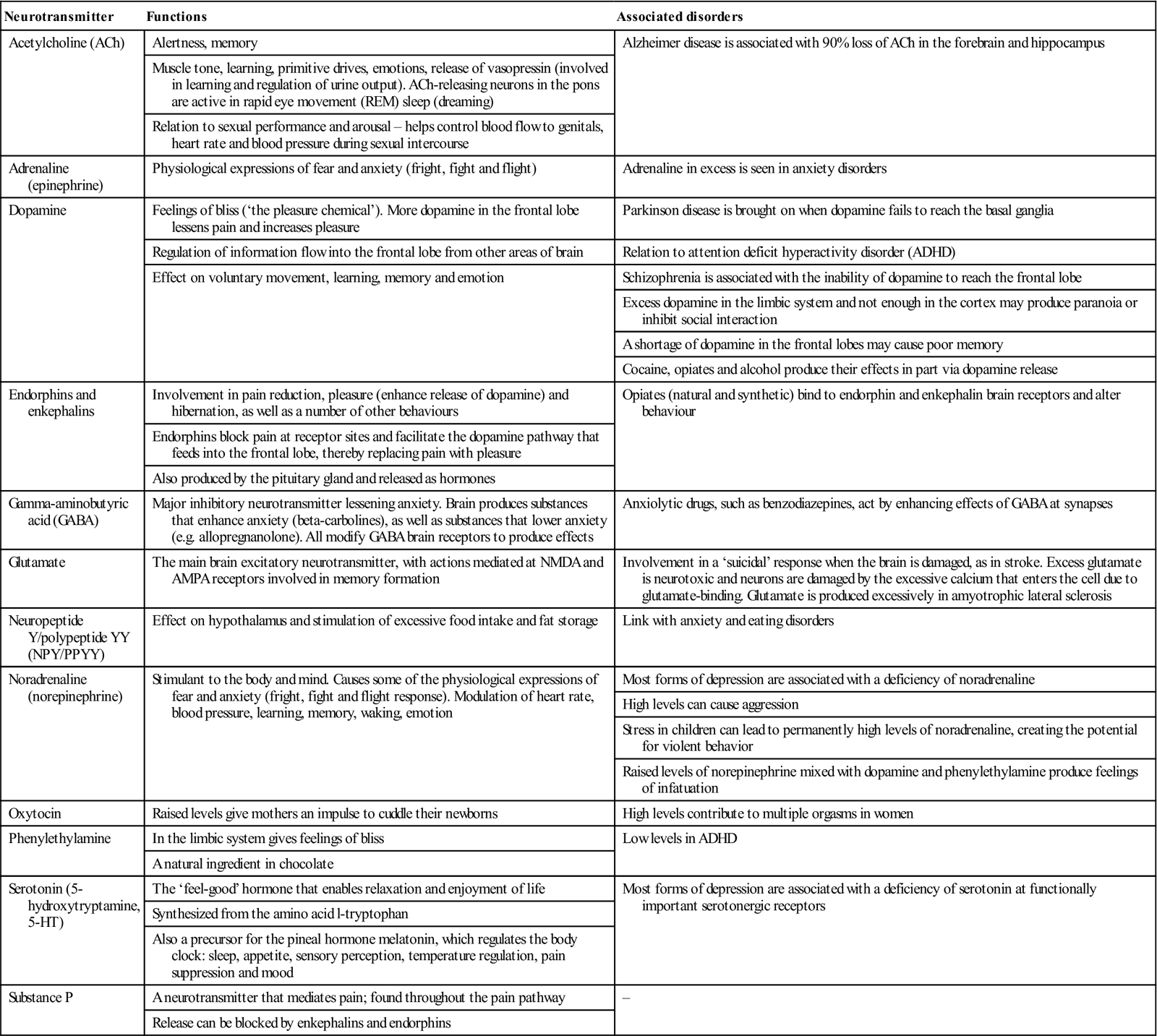

Anxiety can cause several physical effects as a result of overwhelming autonomic activity. Sympathetic activity via the release of catecholamines causes apprehension, tachycardia, hyperventilation, hypertension, sweating, tremor and dilated pupils. Parasympathetic activity may lead to involuntary defecation and urinary incontinence. These changes may be recognized by features such as those listed in Table 10.4.

Table 10.4

< ?comst?>

| Physiological | Behavioural | Cognitive |

| Child | ||

| Adult | ||

| Dry mouth | Verbal abuse | Negative thoughts |

| Excessive talking | ||

| Cancelling appointments, arriving late or not at all | ||

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Pathological anxiety may be difficult to diagnose and requires careful consideration of an individual’s personal history and presenting clinical features. A thorough history and perhaps psychiatric assessment may be appropriate, but underlying organic causes such as hyperthyroidism and mitral valve prolapse should be excluded first.

Anxiety can be classified into the following diagnostic categories:

General management

Treatment of anxiety and stress may require:

■ appropriate management of any underlying organic disease

■ lifestyle changes – to reduce stressors and avoid precipitating factors

Psychotherapy involves talking with a mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker or counsellor, to learn how to deal with problems. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and behavioural therapy are effective for several anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder and social phobia. There are two components to CBT: the cognitive component helps to change thinking patterns that keep people from overcoming their fears, while the behavioural component seeks to change reactions to anxiety-provoking situations. Anxiety disorders may be addressed by exposure (to the object or event of concern) and response prevention – not permitting the compulsive behaviour, to help the individual learn that it is not needed. A key element of this component is exposure, in which people have to confront the things they fear. Behavioural therapy alone, without a strong cognitive component, has been used effectively to treat specific phobias. Here, persons are gradually exposed to the objects or situations that are feared. Often the therapist will accompany them to provide support and guidance. After treatment, the beneficial effects of CBT may last longer than those of medication for people with panic disorder; the same may be true for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder and social phobia.

Drugs can play a part in the treatment of some people with anxiety or phobias. Anti-anxiety medications (anxiolytics) either alter or inhibit the amount or action of a targeted neurotransmitter. Anxiolytics include benzodiazepines (BZPs – which enhance GABA inhibitory activity), serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and azapirones such as buspirone (which act on 5-HT [serotonin]1A receptor). Other drugs, like beta blockers, are used as anxiolytics since they can inhibit some of the physical manifestations, such as rapid heartbeat and sweating. BZPs relieve symptoms quickly with few side-effects, except often for some drowsiness. BZPs include clonazepam, which is used for social phobia and GAD; alprazolam, which is helpful for panic disorder and GAD; and lorazepam, which is also useful for panic disorder. BZPs should be prescribed for short periods of time because of development of tolerance (rising doses to achieve the same effect) and dependence. Panic disorder is an exception, for which BZPs may be used for 6 months to a year. Those who abuse drugs or alcohol are not usually good candidates for BZPs because they can become dependent. Withdrawal symptoms, and in certain instances rebound anxiety, can follow after stopping BZPs. They should not be given to children, the elderly, alcoholics (except to treat withdrawal), or pregnant or lactating women. Temazepam is particularly prone to becoming abused and is a controlled drug. Azapirones (AZPs) are used to treat a range of mental health problems, including anxiety disorders, depression and psychosis. Adverse effects may include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, weakness, insomnia and lightheadedness.

Beta-blockers, such as propanolol, are helpful in certain anxiety disorders, particularly social phobia. Antidepressants can help to relieve anxiety.

Dental aspects

Anxiety can be generated by dental or medical appointments, even amongst normal patients, and is a perfectly natural reaction to an unpleasant experience. A total of 65% of patients report some level of fear of dental treatment. It is essential, therefore, not to dismiss patients who will not accept a proposed treatment as being ‘phobic’ or ‘uncooperative’, though a small number will require psychological or even psychiatric assessment and/or treatment. Younger patients have significantly more fear of treatment than older patients. Among fearful patients, changes in pulse rate (>10 beats/min) and blood pressure are detectable.

Quantification of anxiety levels can be achieved using a modified dental anxiety scale (see Box 2.2). Other scales and a range of techniques to manage such patients are outlined by Rafique et al. (2008).

Dental ‘phobia’ is more extreme than straightforward anxiety, and previous frightening dental experiences are often cited as the major factor in their development. Patients fear the noise and vibration of the drill (56%), the sight of the injection needle (47%) and sitting at the treatment chair (42%) especially. Effects include muscle tension (64%), faster heart beat (59%), accelerated breathing (37%), sweating (32%) and stomach cramps (28%). Patients with a true phobic neurosis about dental treatment are uncommon but, when seen, demand great patience. Phobic patients, who may genuinely want dental care but are unable to cooperate, are often unaware of their anxiety and, as a consequence, may be hostile in their responses or behaviour. Some individuals are difficult or even impossible to manage because of anxiety, phobia or personality disorders.

Patients who apply for treatment at a dental fear clinic are not just dentally anxious; they often show a wide range of other complaints. Persons with clinically significant fear tend to have poorer perceived dental health, a longer interval since their last dental appointment, a higher frequency of past fear behaviours, more physical symptoms during dental injections, and a higher percentage of symptoms of anxiety and depression. They may chatter incessantly, have a history of failed appointments, and appear tense and agitated (‘white knuckle syndrome’).

Dental treatment in anxiety states is usually straightforward. Early morning appointments, with pre-medication and no waiting, can help. The main aids are careful, painlessly performed dental procedures, psychological approaches, confident reassurance, patience and, sometimes, the use of pharmacological agents – for example, anxiolytics such as oral diazepam, supplemented if necessary with intravenous, transmucosal or inhalational sedation during dental treatment. General techniques to help overcome anxiety include relaxation techniques (e.g. deep breathing), distraction (e.g. watching TV), control strategies (e.g. ‘put your hand up if you wish me to stop’) and positive reinforcement (e.g. praise). Other measures include systematic desensitization, biofeedback, modelling and hypnosis, and may need support from a psychologist.

Symptoms such as agitation, slight tachycardia and dry mouth, mainly caused by sympathetic overactivity, are usually controllable by reassurance and possibly a very mild anxiolytic or sedative, such as a low dose of a beta-blocker or a short-acting (temazepam) or moderate-acting (lorazepam or diazepam) BZP, provided the patient is not pregnant and does not drive, operate dangerous machinery or make important decisions for the following 24 hours. Temazepam 10 mg orally on the night before and 1 hour before dental treatment can be used to supplement gentle sympathetic handling and reassurance of the anxious patient. Intravenous or intranasal sedation with midazolam, or relative analgesia using nitrous oxide and oxygen, is also useful. BZP metabolism is impaired by azole antifungals, and by macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin and clarithromycin. Alcohol, antihistamines and barbiturates have additive sedative effects with BZPs. The analgesic dextropropoxyphene should be avoided in patients taking alprazolam, as it may cause toxicity.

Difficulties may also result from alcoholism or drug dependence, or drug treatment with major tranquillizers, MAOIs or TCAs. Oral manifestations, such as facial arthromyalgia, dry mouth, lip-chewing or bruxism, may be complaints in chronically anxious people. Cancer phobia is also an indication of an anxiety.

Stress

General aspects

The brain areas involved in regulation of stress responses include the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus and nucleus accumbens. Acute stress enhances immune function whereas chronic stress suppresses it.

Besides the hypothalamus and brainstem, which are essential for autonomic and neuroendocrine responses to stressors, higher cognitive areas of the brain play a key role in memory, anxiety and decision-making, and are targets of stress and stress hormones. The effects of glucocorticoids on the hippocampus and other brain regions are regulated by: corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG), multiple drug resistance P-glycoprotein (MDRpG), and metabolism by 11-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11-HSD-1). Four peptide/protein hormones – IGF-1, insulin, ghrelin and leptin – affect the hippocampus.

Different alleles of commonly occurring genes determine how individuals will respond to stress. For example, the serotonin transporter is associated with alcoholism, and individuals who have one allele are more likely to respond to stress by developing depression. Individuals with an allele of the monoamine oxidase A gene are more vulnerable to abuse in childhood and more likely to become abusers themselves and to show antisocial behaviours. Stress begins in and affects the brain, as well as the rest of the body. Acute stress responses promote adaptation and survival via neural, cardiovascular, autonomic, immune and metabolic responses. Chronic stress can promote and exacerbate pathophysiology through the same systems. The burden of chronic stress and accompanying changes in personal behaviours (smoking, eating too much, drinking, poor-quality sleep – otherwise referred to as ‘lifestyle’) is called allostatic overload. Brain regions such as the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and amygdala respond to acute and chronic stress and show changes in morphology and chemistry that are largely reversible if the chronic stress lasts only for weeks. However, it is not clear whether prolonged stress for many months or years may have irreversible effects.

In obese individuals, the final common pathway of the stress response – the HPA axis – is altered, and concentrations of cortisol are raised in adipose tissue due to raised activity of 11β-HSD-1. Short sleep and decreased sleep quality are also associated with obesity. In addition, sleep curtailment induces HPA-axis alterations that, in turn, may negatively affect sleep.

CRH plays a central role in the regulation of the HPA axis. CRH action on ACTH release is potentiated by vasopressin, whereas oxytocin inhibits it. ACTH release results in the release of corticosteroids from the adrenals, which subsequently, through mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors, exert negative feedback on the hippocampus, the pituitary and the hypothalamus. The most important glucocorticoid in humans is cortisol. Vasopressin production is increased in depression. The suprachiasmatic nucleus, the biological clock of the brain, shows lower vasopressin production and a smaller circadian amplitude in depression, which may explain the associated sleep problems. The hypothalamo–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis is inhibited in depression. Although cortisol and CRH may well be causally involved in depression, there is no evidence for any major irreversible damage in the hippocampus in depression.

The stress response is mediated by the HPA system and reliant on activity of the CRH neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN). The CRH neurons co-express vasopressin (ADH), which potentiates the CRH effects. CRH neurons regulate the adrenal innervation of the autonomic system and affect mood. Both centrally released CRH and increased levels of cortisol contribute to the features of depression. Depression is also a frequent side-effect of steroid treatment and is one of the symptoms of Cushing syndrome. The ADH neurons in the hypothalamic PVN and supraoptic nucleus are also activated in depression, which contributes to the increased release of ACTH from the pituitary. Increased levels of circulating ADH are also associated with the risk for suicide. The prevalence, incidence and morbidity risk for depression are higher in females than in males and fluctuations in sex hormone levels are considered to be involved.

Causes of stress

The causes of stress can be different for each person and individuals vary in their ways of coping.

Clinical features of stress

Stress is a reaction caused by anything that requires adjustment to a change in the environment. The reactions can be physical, mental/behavioural and/or emotional. Emotional stress can release chemicals that provoke brain blood vessel changes, which in turn can trigger tension (stress) headaches. The sympathetic nervous system turns on the fight or flight response with adrenaline (epinephrine) release; the brain limbic system immediately responds. Cortisol secretion rises but other hormones shut down; growth, reproduction and the immune system are suppressed. Later, the tranquillizing parasympathetic nervous system activates to calm things down.

Tension headaches can be either episodic or chronic. Episodic tension headache is usually triggered by an isolated stressful situation or a build-up of stress; it can usually be treated by analgesics. Daily stress, such as from a high-pressure job, can lead to chronic tension headaches. Treatment for chronic tension headaches usually involves counselling, stress management and possibly anxiolytics or antidepressants.

Coping with stress

The key to coping with stress is identifying stressors, learning ways to reduce stress and managing stress. Coping is a process, not an event.

Helpful advice includes the following measures:

■ Lower your expectations; accept that there are events beyond your control

■ Take responsibility for the situation

■ Be assertive rather than aggressive

■ Maintain emotionally supportive relationships

■ Maintain emotional composure

■ Try to change the source of stress and distance yourself from it

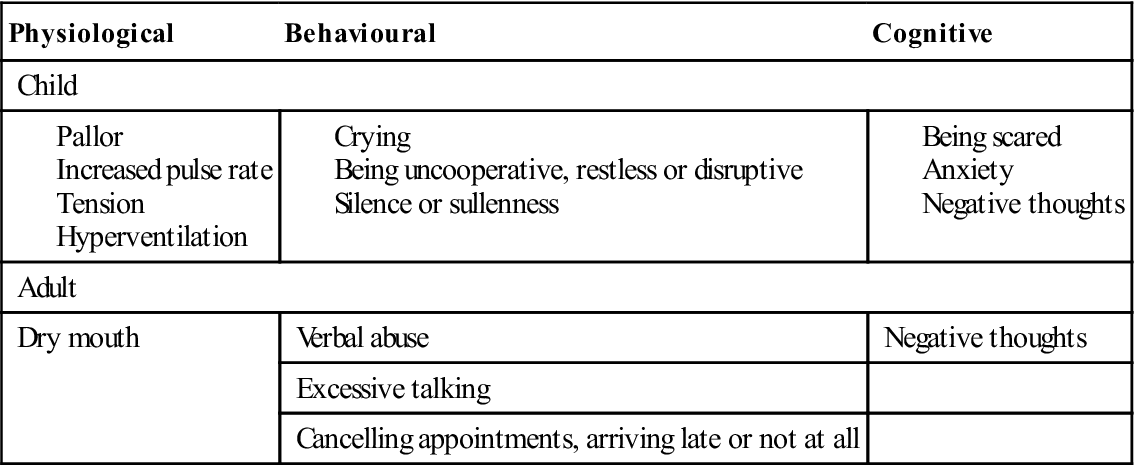

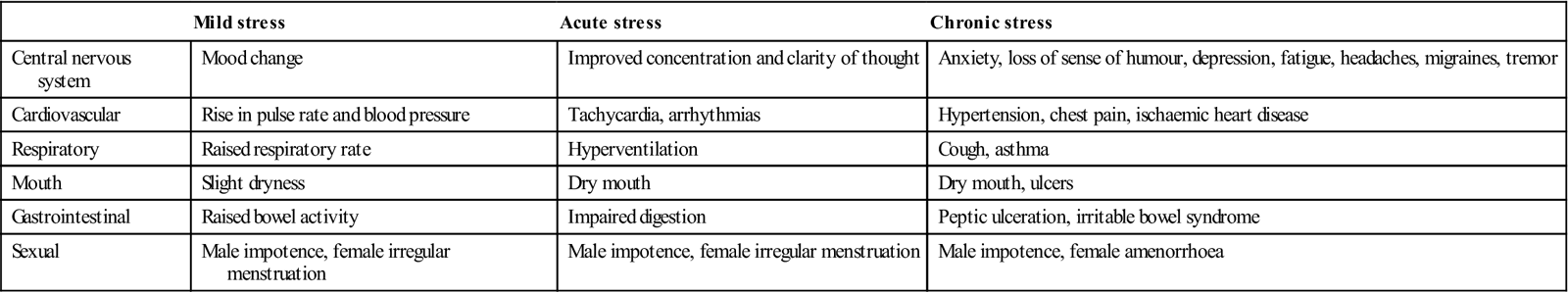

Stress may play a greater role in health and disease than formerly supposed. Humans are sensitive to stressors (e.g. operations) and even visits for health care can activate the HPA system. Anxiety generated by such ordeals as dental or medical appointments, or by public speaking, solo musical performances, examinations or interviews, is normal. Stress is also fairly common in dental students and staff. Work stressors may include examinations, fear of failure, difficulties with accommodation or study facilities, inadequate holidays or relaxation time, financial difficulties, criticism, and time and scheduling demands. Stress can lead to reactions affecting a wide range of functions (Table 10.5).

Table 10.5

Some possible effects of acute and chronic stress

< ?comst?>

| Mild stress | Acute stress | Chronic stress | |

| Central nervous system | Mood change | Improved concentration and clarity of thought | Anxiety, loss of sense of humour, depression, fatigue, headaches, migraines, tremor |

| Cardiovascular | Rise in pulse rate and blood pressure | Tachycardia, arrhythmias | Hypertension, chest pain, ischaemic heart disease |

| Respiratory | Raised respiratory rate | Hyperventilation | Cough, asthma |

| Mouth | Slight dryness | Dry mouth | Dry mouth, ulcers |

| Gastrointestinal | Raised bowel activity | Impaired digestion | Peptic ulceration, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Sexual | Male impotence, female irregular menstruation | Male impotence, female irregular menstruation | Male impotence, female amenorrhoea |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Fear, an emotion that deals with danger, causes an automatic, rapid protective response in many body systems, coordinated by the amygdala. Emotional memories stored in the central amygdala may play a role in disorders involving very distinct fears, such as phobias, while different parts may be involved in other forms of anxiety.

The hippocampus – an area of the brain critical to memory and emotion – is involved in intrusive memories and flashbacks typical of post-traumatic stress disorder, and results in raised levels of stress hormones – cortisol, adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

Danger induces high levels of enkephalins and endorphins, natural opioids, which can temporarily mask pain, and in some anxiety states higher levels persist even after the danger has passed.

Cortisol is the major steroid hormone produced in the adrenal glands and is essential for the body to cope with stress. Cortisol levels exhibit a natural rise in the morning and fall at night. If this rhythm is disturbed, mineral balance, blood sugar control and stress responses are affected. Lack of cortisol can lead to fatigue, allergies and arthritis, while excess cortisol can have an even greater negative effect on the body. While short-term elevations of cortisol are important for dealing with the stress of life-threatening issues, illness and wound-healing, chronically elevated levels can result in tiredness, depression and accelerated ageing with hypertension, muscle loss, bone destruction, obesity and diabetes. Prolonged stress or prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids can also have adverse effects on the hippocampus to cause atrophy, and memory deficits such as have been demonstrated in Cushing syndrome, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), the most abundant steroid hormone in the body, appears to counter the effects of high levels of cortisol and improves the ability to cope with stress. Low levels of DHEA have been associated with impaired immunity, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer disease, hypothyroidism and diabetes.

Anxious or stressed patients may require drugs to control the anxiety but they respond better to beta-blocking agents (such as propranolol) than to BZPs, and with less impairment of performance. Stress may lead to substance abuse (Ch. 34). Anxiety may be caused or aggravated by using caffeine or street drugs like amphetamines, LSD or ecstasy.

Stress in dental staff

Dentistry can be a stressful occupation for both the dentist and the ancillary staff. There appears to be a significant level of dissatisfaction amongst dental nurses and hygienists in general practice, in terms of working conditions, relations with other staff and management skills of the dentist.

Increasingly, dentists in general practice appear concerned about the business aspects of practice, and seem to experience more physical and mental ill-health compared with other health professionals. In contrast, community dentists may be more worried about clinical matters, such as treating medical emergencies or difficult patients.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

General aspects

Post-traumatic stress disorder is an anxiety state that can follow exposure to a terrifying event where victims can see danger, where life is threatened, or where they see other people dying or being injured. Traumatic events that can trigger PTSD include personal assaults, such as rape or mugging, disasters, accidents or military combat.

Many people with PTSD repeatedly re-experience the ordeal in the form of flashback episodes, memories, nightmares or frightening thoughts, or being ‘on guard’, especially when exposed to events or objects reminiscent of the trauma. Anniversaries of the event can also trigger symptoms. Most people with PTSD thus try to avoid any reminders or thoughts of the ordeal (avoidance and numbing).

Clinical features

Symptoms of PTSD typically begin within 3 months of the traumatic event but occasionally not until years later. Headaches, gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, chest pain or discomfort elsewhere can be disabling. Emotional numbness and sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety, irritability, outbursts of anger and feelings of intense guilt are common.

Associated depression, alcohol or other substance abuse, or another anxiety disorder is also common.

General management

CBT, group therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and exposure therapy, in which patients gradually and repeatedly relive the frightening experiences under controlled conditions to help them work through the trauma, can be effective. Medications, particularly SSRIs, are frequently prescribed (TCAs are as effective), and help to ease associated symptoms of depression and anxiety and to promote sleep.

Dental aspects

Frightening though dentistry may be, it is not known to have precipitated PTSD. However, patients who are suffering from PTSD may present with a variety of unexplained pain problems.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

General aspects

Generalized anxiety disorder differs from normal anxiety in that it is chronic and fills the day with exaggerated and unfounded worry and tension. GAD is twice as common in women as in men.

Clinical features

People with GAD are always anticipating disaster, often worrying excessively about health, money, family or work; they may have physical symptoms, such as fatigue, headaches, muscle tension, muscle aches, difficulty in swallowing, trembling, twitching, irritability, sweating and hot flushes, and trouble falling or staying asleep. Unlike individuals with other anxiety disorders, people with GAD do not characteristically avoid certain situations. GAD is often accompanied by other conditions associated with stress, such as irritable bowel syndrome. GAD may be accompanied by another anxiety disorder, depression or substance abuse.

General management

Generalized anxiety disorder is diagnosed when someone spends at least 6 months worrying excessively about everyday problems. GAD is commonly treated with CBT and BZPs such as clonazepam or alprazolam. Venlafaxine, a drug closely related to the SSRIs, is also useful. Buspirone, an azapirone, is also used: it must be taken consistently for at least 2 weeks to achieve effect, and possible adverse-effects include dizziness, headaches and nausea.

Panic Disorder

General aspects

Panic disorder is the term given to recurrent unpredictable attacks of severe anxiety with physical symptoms such as palpitations, chest pain, dyspnoea, paraesthesiae and sweating (‘panic attacks’). There are associations with mitral valve prolapse in 50%.

Clinical features

Panic attacks can come at any time, even during sleep. In a panic attack, there are features of catecholamine release – the heart pounds and the patient may feel sweaty, weak, faint or dizzy. The hands may tingle or feel numb, and there may be nausea, chest pain, a sense of unreality or fear of impending doom.

Many or most of the symptoms may result from hyperventilation. An attack generally peaks within 10 minutes but some symptoms may last much longer. Many individuals suffer intense anxiety between episodes, worrying when and where the next attack will strike.

Panic disorder is often accompanied by other conditions such as depression, drug abuse or alcoholism, and may lead to a pattern of avoidance of places or situations where panic attacks have struck.

General management

Panic disorder is one of the most readily treatable disorders and usually responds to psychotherapy or medication with alprazolam or lorazepam. Fluoxetine or another SSRI is frequently prescribed but TCAs are as effective. Hyperventilation is effectively treated by rebreathing into a paper bag.

Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder)

General aspects

Social phobia involves overwhelming anxiety and excessive self- consciousness in normal social situations, resulting in a persistent, intense and chronic fear of being watched and judged by others and being embarrassed or humiliated by one’s own actions. Women and men are equally likely to develop social phobia, usually beginning in childhood or early adolescence.

Clinical features

Accompanying physical symptoms may include blushing, profuse sweating, trembling, nausea and difficulty in talking. Anxiety disorders and depression are common and substance abuse may develop.

General management

Social phobia can usually be treated successfully with psychotherapy or medications. Beta-blockers, such as propanolol or clonazepam, are helpful. Fluoxetine or other SSRIs are frequently prescribed but TCAs are as effective.

Specific Phobias (Phobic Neuroses)

General aspects

A phobia is a morbid fear or anxiety out of all proportion to the threat, an intense irrational fear of something that poses little or no actual danger. Twice as common in women as in men, phobias usually appear first during childhood or adolescence and tend to persist into adulthood.

Clinical features

Phobic neuroses differ from anxiety neuroses in that the phobic anxiety arises only in specific circumstances, whereas patients with anxiety neuroses are generally anxious. Claustrophobia (fear of closed spaces) is probably the most common phobic disorder. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sometimes impossible to carry out because of claustrophobia.

Some of the other more common specific phobias are centred around heights, tunnels, driving, water, flying, insects, dogs and injuries involving blood. When phobias are centred on threats such as flying, anaesthetics or dental treatment, normal life is possible if such threats are avoided. Phobias may also be a minor part of a more severe disorder, such as depression, obsessive neurosis, anxiety state, personality disorder or schizophrenia.

General management

Specific phobias are highly treatable with carefully targeted psychotherapy. Behaviour therapy aims at desensitization by slow and gradual exposure to the frightening situation. Implosion is a technique in which patients are asked to imagine a persistently frightening situation for 1 or 2 hours. Phobias can sometimes be controlled by anxiolytic drugs. Buspirone is particularly useful, since it lacks the psychomotor impairment, dependence and some other effects of BZP use. Antidepressants, especially TCAs, are used if there is a significant depressive component.

Personality Disorders

In mental health, the word ‘personality’ refers to the collection of characteristics or traits that makes each of us an individual, including the ways that we think, feel and behave.

Personality may develop in a way that makes it difficult for us to live with ourselves and/or other people – traits or disorders usually noticeable from childhood or early teens. Personality disorders are chronic abnormalities of character or maladjustment to life that shade into neuroses or psychoses and may make it difficult to make or keep relationships, get on with friends and family or with people at work, keep out of trouble or control feelings or behaviour. However, insight is retained and most patients manage to pursue a relatively normal life. Personality disorders are shown in Table 10.6.

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses