PART 1 – PATIENT AND PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

Chapter 1

THE CAUSES OF FAILURE

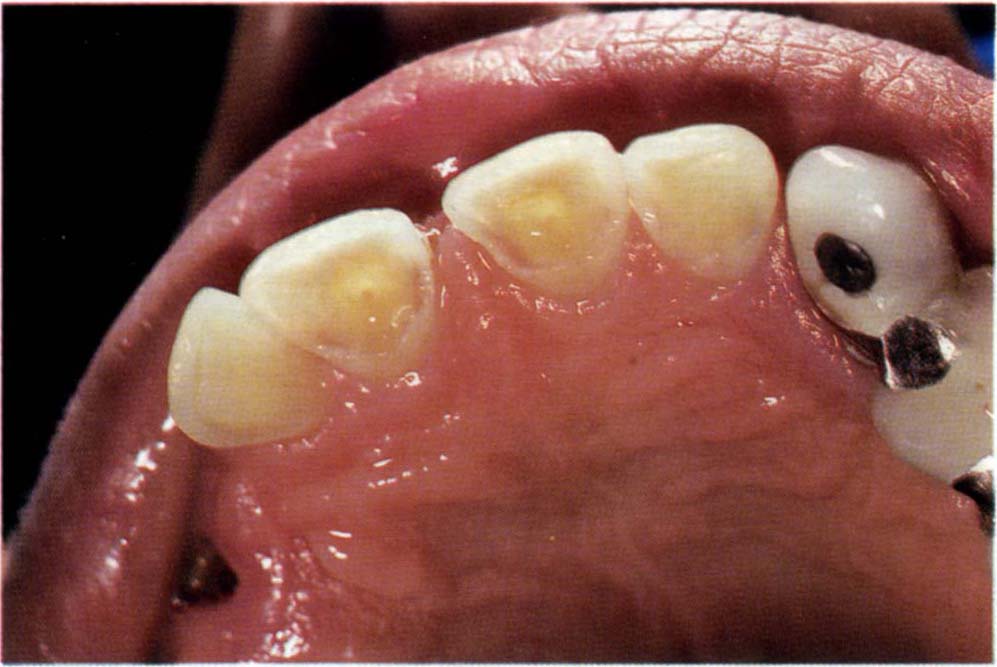

Presentation (Fig 1-1)

The patient with a failed restored dentition will present for one or more of the following reasons:

- Pain, usually affecting the mouth, face and/or temporomandibular joints.

- Inability to function, which can be:

– total, that is the dentition is unusable;

– localized, such as painful or highly mobile teeth, speech problems.

- Dissatisfaction with aesthetics.

- Broken teeth and/or restorations.

- Inflammatory swelling.

- Bad taste.

- Bad breath (halitosis), having been informed by another person.

- Bleeding gums.

- Anxiety

– primarily of dental origin related, for example to loose teeth or restorations;

– of psychogenic origin, aggravated by dental treatment.

- By referral with a symptom-free restorative problem.

Underlying Causes and Associated Symptoms

It is not the aim of this section to describe all causes in detail, nor to provide a comprehensive guide to symptoms. The underlying causes will be listed and some pertinent aspects considered.

General Pathosis (Figs 1-1a+b)

Failure to diagnose a “pathological change, which would have far greater bearing on the patient’s life expectancy or quality of life than any shortcomings of the restorations themselves, is failure. A general medical history is essential – the prescription of two years of virtually continuous restorative dentistry for a patient with an 18 month life prognosis is failure! All patients should have a general examination of the facial tissues extra-orally and the soft tissues intra-orally prior to a more intensive dental examination.

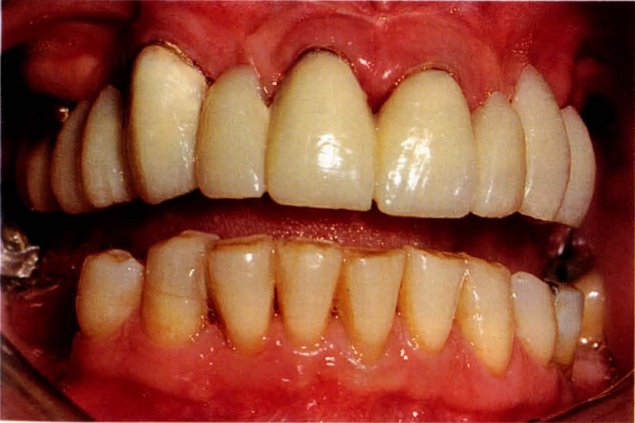

Fig. 1-1a Uncemented bridge, unstable removable partial denture distal to 13 and 23, and periodontitis. The patient was referred for bridge replacement and possibly implant placement.

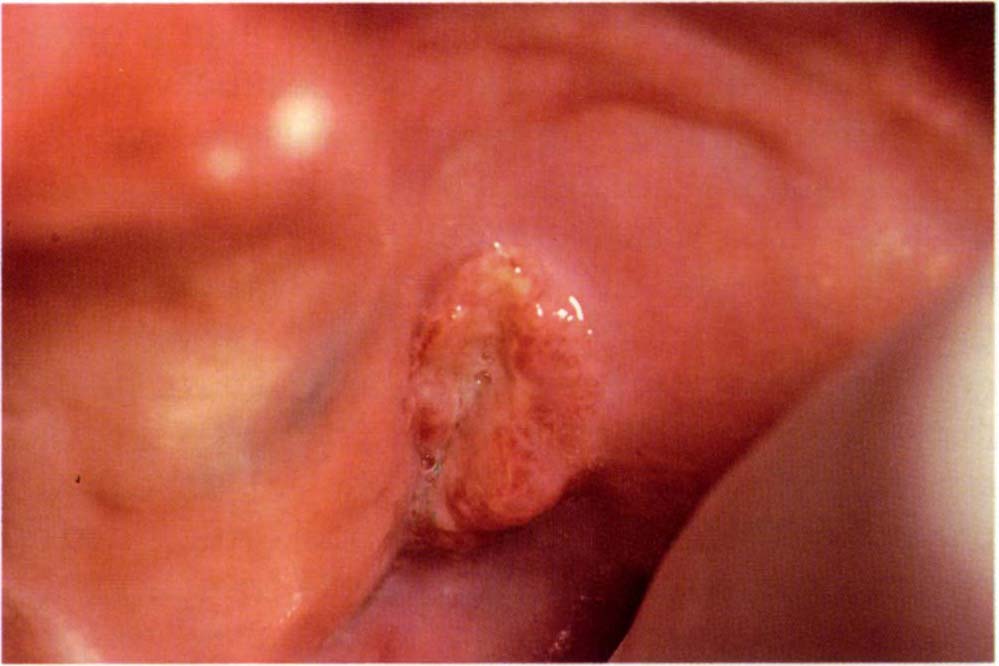

Fig. 1-1b A squamous cell carcinoma in the buccal sulcus distal to tooth 28 which is obviously of greater concern than the failed restoration.

A change in a patient’s medical condition, for example, following a cerebral haemorrhage, may alter the patient’s motivation, physical ability to maintain the dentition, diet and general resistance, leading to a deterioration of restorations and abutments.

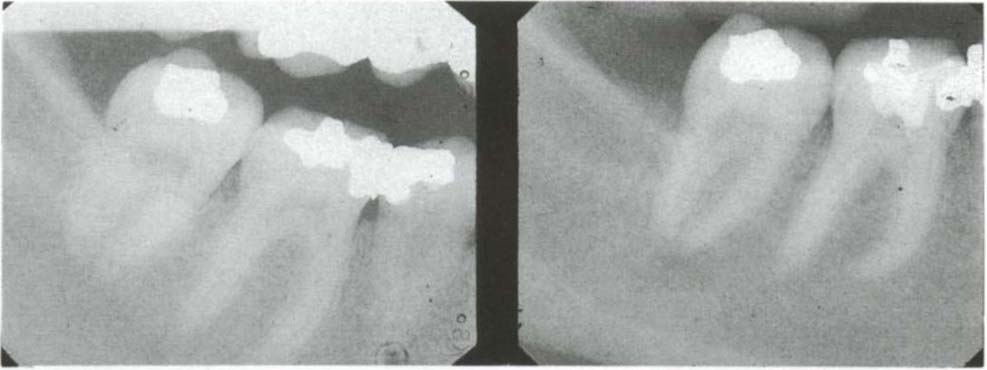

Periodontal (Figs 1-1c+d)

This is usually perceived by the patient as:

- Looseness of teeth or bridgework.

- Drifting teeth.

- Bleeding tissues.

- Changes in colour of the gums.

- Bad taste.

- Bad breath.

- Pain, which is sometimes relieved by applying sideways pressure from an opposing tooth.

- Abscess formation.

- Poor aesthetics.

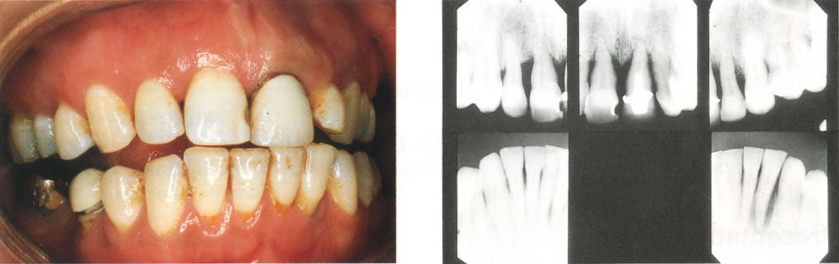

Figs 1-1c and d Eight months following restoration. Consider the bone loss, yet the gingival tissues look relatively normal, a periodontal examination may not have been carried out at the time of crowning. The maxillary anterior teeth were becoming mobile and so the patient sought advice.

Publications have indicated that periodontitis is cyclic in nature and site-specific, rather than a generalized and necessarily progressive, destructive condition.1, 2 Furthermore, the commonly used diagnostic criteria, such as bleeding on probing and pocket depth, are poor predictors as to whether a periodontal lesion is progressive.3–5 An absence of previous radiographs and charting, as is often the case for new patients, makes it impossible to ascertain whether further bone and attachment loss has occurred since the restorations were placed. However, the patient who presents with loss of attachment, pocketing, bleeding on probing, possibly with pus exudate obviously has a different disease susceptibility to the patient who presents with 2 mm to 3 mm crevice depths, no loss of attachment, dense bone and heavily worn and/or fractured restorations.

Even with virtually ideal treatment in extensively restored, advanced periodontitis cases, in 1984, Lindhe and Nyman6 found a 1.2% loss of abutments over a 14-year period, due to a recurrent untreatable loss of attachment. Schwartz et al. in 1970,7 reported that 11.2% of failure in patients with restored dentitions was due to periodontal disease or mobility. It is perhaps somewhat disheartening to consider the results of the following studies. It has been reported that only a small percentage of existing pockets become active at some time.2, 3, 8 It is highly probable that clinical signs are primarily indicators of past disease and not predictors of future disease. Further, root planing and surgical approaches are almost equally effective in controlling disease, as measured by current criteria.9–10 However, it can be concluded that these treatment studies include some 97.9% of inactive sites2 and it is highly probable that most test teeth would not have had further loss of attachment, even without treatment; that is treatment was applied to sites that did not have active disease. The problem for the researcher, as for the clinician, is that the diagnostic criteria (described on pages 73–85) are so unreliable, that we are unable to determine which sites will, in the absence of treatment, deteriorate in the future. Further, it is very difficult to assess the true efficacy of treatment. It is likely that the current crude diagnostic techniques will be replaced by precise biochemical and bacteriological testing.11 Until this occurs, it must be appreciated that the ability to predict future periodontal disease remains severely handicapped.

Periimplant (Figs 1-1e–h)

Mechanical failures, loss of integration and infection may be perceived by the patient as:

- Pain.

- Movement of bridgework.

- Swelling.

- Bad breath.

- Bad taste.

- Alteration in sensation to the lip (paraesthesia) or numbness of the lip (anaesthesia).

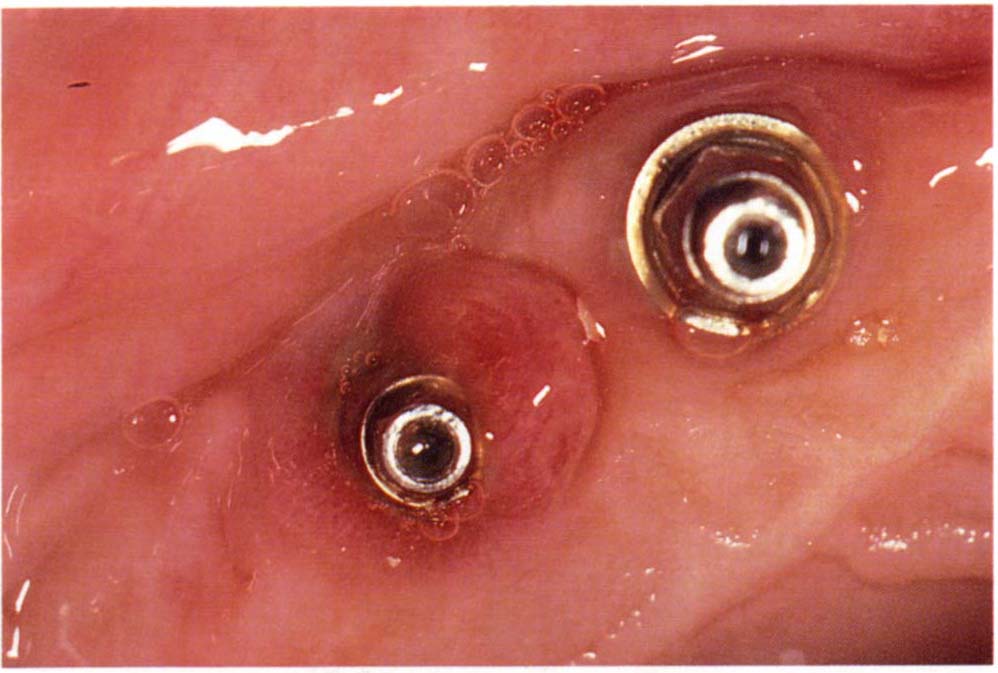

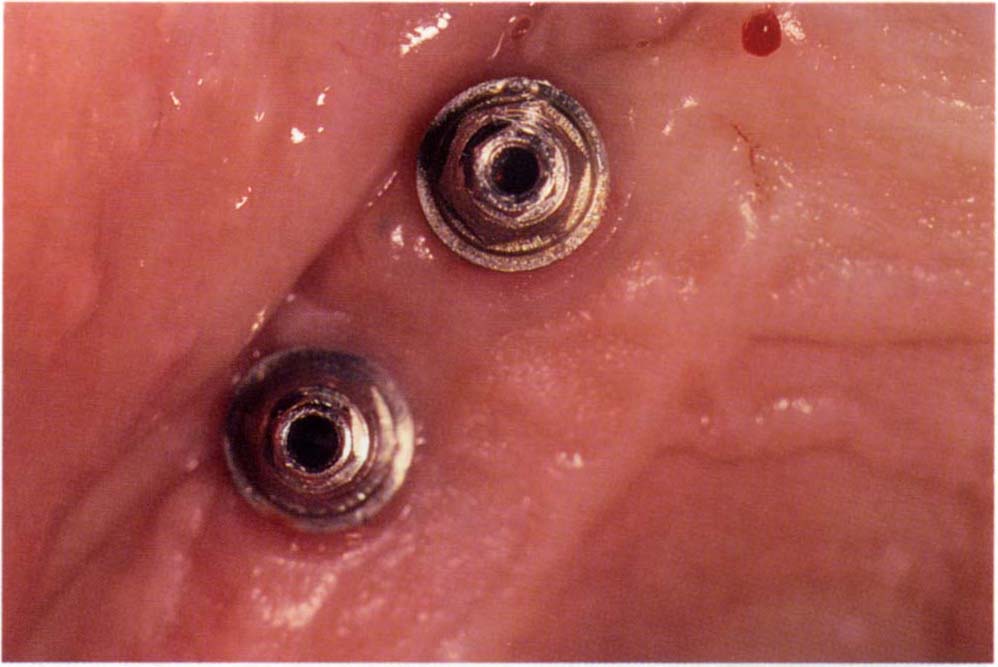

Fig. 1-1e (i) Soft tissue lesion associated with incomplete seating of an abutment cylinder.

Fig. 1-1e (ii) Two weeks following removal of the abutment, ultrasonic cleaning of the abutment in 0.20% chlorhexidine gluconate, irrigating the fixture head with the same, removing granulation tissue with a titanium tipped currette and reseating.

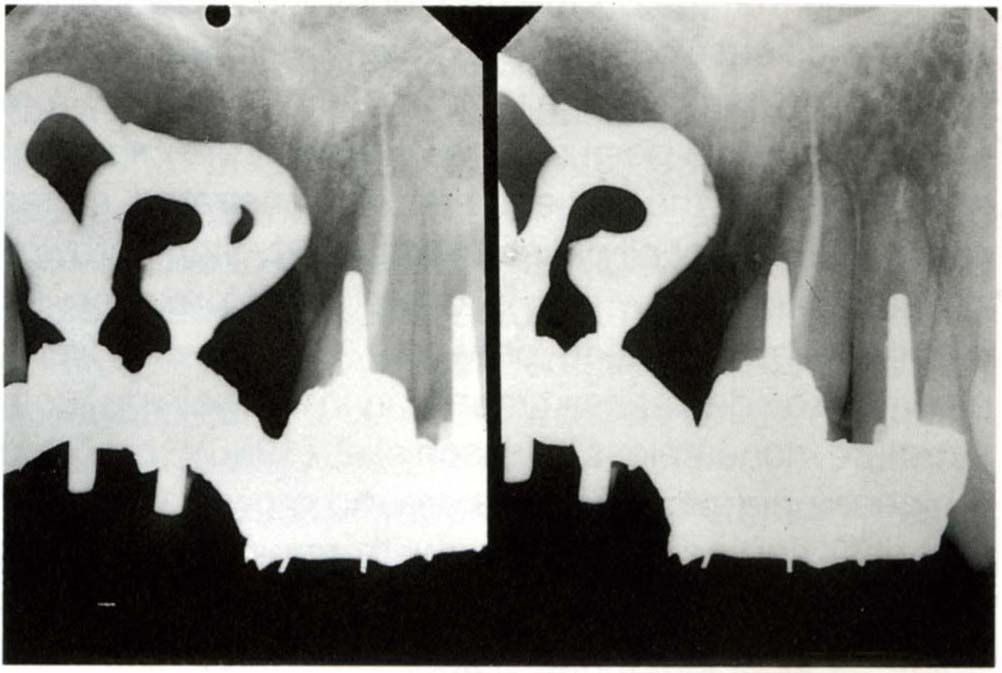

Fig. 1-1f (i) Failure of osseointegration. The maxillary fixtures are too close to one another and there is a radiolucency both mesially and distally around the anterior fixture, which was loose. Two of the mandibular fixtures are unnecessarily short. One exhibits a perifixture radiolucency and has not integrated, possibly due to overheating during preparation.

Fig. 1-1f (ii) There is a radiolucent area around the entire fixture. The fixture was mobile and besides non-integration, had been placed too close to the adjacent tooth.

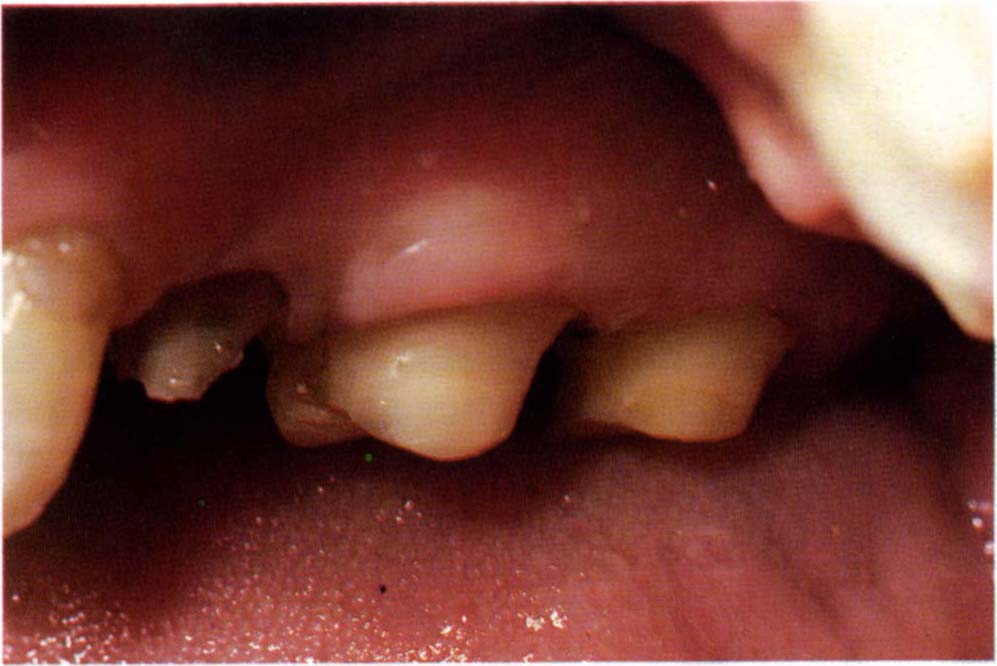

Fig. 1-1g Failure of blade implant.

Fig. 1-1h Radiographic appearance. Note the bone loss and root perforation.

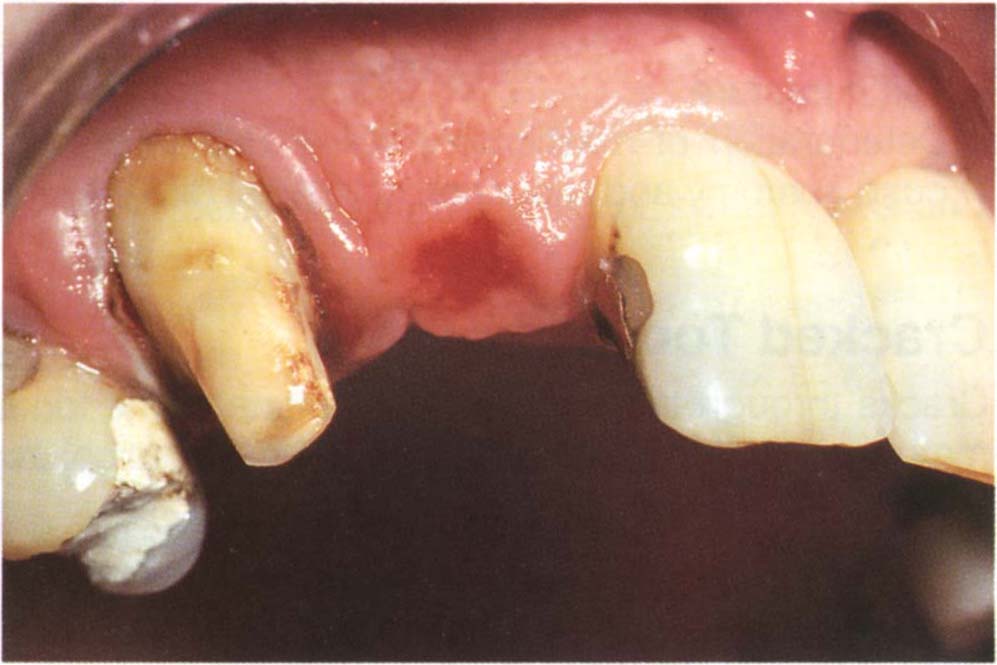

Caries (Figs 1-1i+j)

This is usually perceived by the patient as:

- Pain or sensitivity to hot, cold or sweet foods and liquids.

- Bad taste.

- Bad breath.

- Loose restorations.

- Fractured teeth.

- Discoloured teeth.

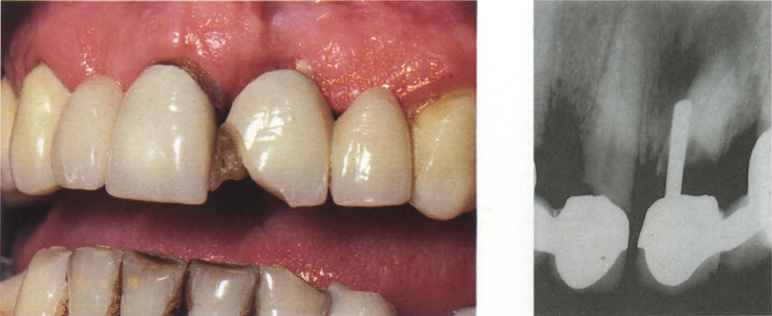

Figs 1-1i and j Clinical view and radiographs: Failure after one year due to root perforation, caries and fractured porcelain.

Caries may be present beneath restorations, at the margins of restorations or on the roots. Schwartz et al. (1970)7 and Randow et al. (1986)12 both reported caries to be the most frequent cause of failure (36%; 18.3%) of existing restorations. Glantz et al. in 199313 reported that of 77 bridges reviewed at 15 years, 32.5% required removal. Of these 9.6% were removed because of untreatable caries of the abutments. Glantz et al. reported further in 199314 that the incidence of caries was not related to the age of the patient, rather, to the time that the bridge had functioned. Frequently, endless discussion with the patient revolves around whether the caries is due to poorly fitting crowns. From the management point of view, however, the important aspect is that the patient has demonstrated caries susceptibility. Not all patients with poorly fitting crowns develop caries – which is obviously no excuse for providing poorly fitting crowns – nor do well fitting crowns provide caries immunity in the remaining tooth structure, nonetheless Karlsson et al. (1986)15 reported a higher incidence of caries around crowns with poor margins, compared to those with good margins. An assessment of disease susceptibility and control is essential prior to formulating a definitive plan of treatment. Unfortunately, as is clearly pointed out by Bibby et al. (1977)16 and Anderson et al. (1993)17 the diagnostic predictors for dental caries are poor.

Root surface caries is strongly associated with gingival recession and periodontal pockets. It is most prevalent amongst the elderly population and it is probable that this is associated with the reduced salivary flow resulting from many of the drugs prescribed for this population. Examples of such drugs are beta blockers, mood altering drugs and diuretics.18–23

Pulpal (Fig 1-1k [i])

This is usually perceived by the patient as:

- Pain – either spontaneous or related to hot/cold or sweet stimuli.

- Pain which is accentuated by lying down or exercise.

Fig. 1-1k (i) Over-prepared teeth. It is all too easy with air turbine instrumentation to rapidly cut, but over-prepare, many teeth whilst applying inadequate cooling.

Pulpal pain can be acute or chronic and can be precipated during crown preparation. Extensive bridgework is often fabricated on teeth that already have compromised pulps through previous caries and restorations. It is all too easy with air turbine instrumentation, to rapidly cut butoverprepare many teeth, whilst applying inadequate cooling.24 Dehydration of the teeth that are cut first and left unprotected may occur while the remainder of the teeth are prepared. Excessive preparations are often made on distal abutment teeth to ensure retention of distal abutment crowns13. Poor diagnostic techniques make it difficult to determine which teeth require endodontic intervention. Periapical radiolucencies on non-endodontically treated non-vital teeth, indicate the need for treatment, but the tooth stump with a diminished response to vitality testing presents a diagnostic problem. Is the lack of response due to pulpal pathosis or physiological adaptation? How do we make the diagnosis? Which aspects influence whether or not treatment is recommended. Reuter and Brose25 reported in 1984 that very few abutment teeth monitored over an 11-year period, required subsequent endodontic treatment, even though they were heavily restored prior to bridge fabrication. However, when endodontic treatment was later required, there was a good chance that subsequent restorative failure would occur, leading to the need for bridge replacement. The inference is that doubful pulps should be treated prior to bridge fabrication. Randow et al. (1986)12 found that there was a higher risk of mechanical failure in root treated end abutments than in vital end abutments implying that vitality should be retained if possible. However, failure to treat, with subsequent endodontic problems arising beneath a replacement bridge, is also highly undesirable.

Erosion (Fig 1-1k [ii])

Erosive loss of tooth tissue can be due to dietary factors, for example, it could be induced by drinking lemon juice or carbonated drinks, or it may be idiopathic, that is, it could be self-originated, with no apparent external cause. It is usually perceived by the patient as:

- Sensitivity to temperature change or acidulated food.

- Spontaneous pain due to pulpal exposure.

- Alteration in appearance due to thinning of anterior teeth, or loss of vertical dimension.

- Tooth fracture.

- Deterioration of masticatory ability due to loss of cusp anatomy and reduction of vertical dimension.

Fig. 1-1k (ii) Erosion leading to pulp exposure 11, 21 and thinning of the teeth.

Cracked Tooth (Figs 1-1l+m)

Cracks through the enamel and dentine of the tooth may occur and are usually perceived by the patient as:

- Pain to hot and cold foods and to biting or on release of biting pressure.

- Loss of tooth substance following actual fracture.

Fig. 1-1l Mesio-distal crack, passing vertically through the distal root of tooth 47.

Endodontal (Figs 1-1m)

This is usually perceived by the patient as:

- Pain on biting.

- Swelling.

- They may report previous pain (pulpal) which subsided.

Fig. 1-1m Radiographs, (i) 47 in 1991; (ii) 47 in 1992. Consider the periapical radiolucency which is associated with the crack. Tooth 46 had been opened without reference to a radiograph. The cause of the pain was tooth 47.

Inflammation of the periodontium from endodontic causes may be periapical, perifurcal or lateral. It can arise from pulpal necrosis, inadequate endodontics, root perforation or fracture. Inadequate endodontics may be due to difficult tooth anatomy or access, but a subjective impression concludes that too many failures of iatrogenic aetiology are needless. Primary endodontic lesions can be confluent with marginal periodontal lesions and vice-versa.26

Karlsson (1986)15 reported that 10% of 641 bridge abutments exhibited periapical lesions 10 years after cementation and that 19.8% of 303 root filled abutments exhibited non-healed periapical lesions. Palmquist et al. (1993)27 reported that after 18–23 years of service, 10% of vital crowns and abutments (38 of 365), had been removed whereas 24% of endodontically treated crowns and abutments had been removed (29 of 122). Regardless of cause, one must be realistic. Untreatable endodontic failure on a principal abutment leads to failure.

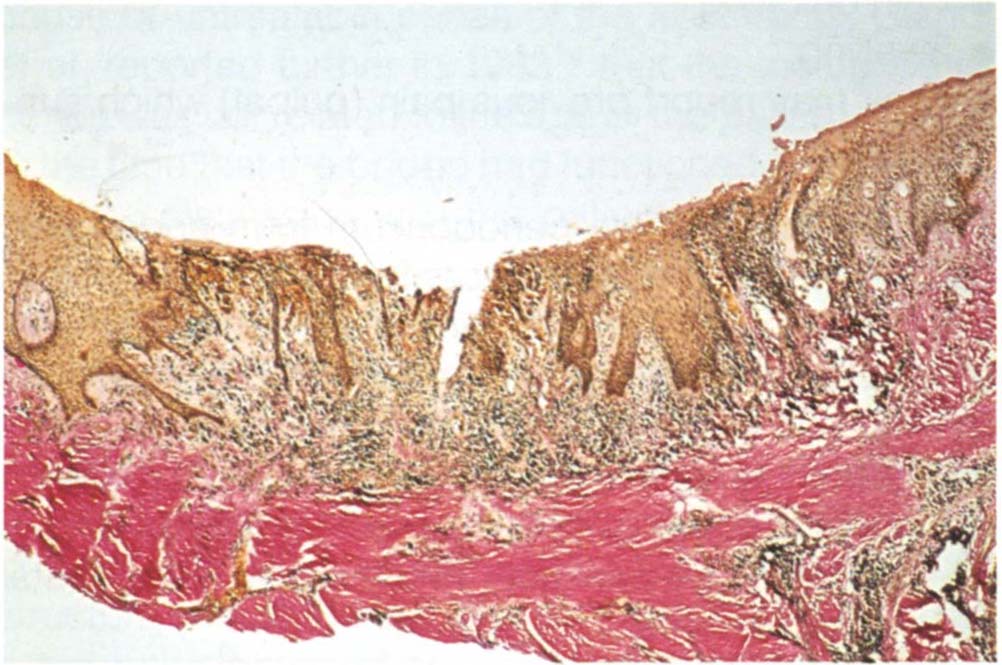

Subpontic Inflammation (Fig 1-1n+o)

Subpontic inflammation is usually perceived by the patient as:

- Pain.

- Swelling.

- Bad breath.

- Bad taste.

- Bleeding gums.

- Poor aesthetics.

Fig. 1-1n Subpontic red patch.

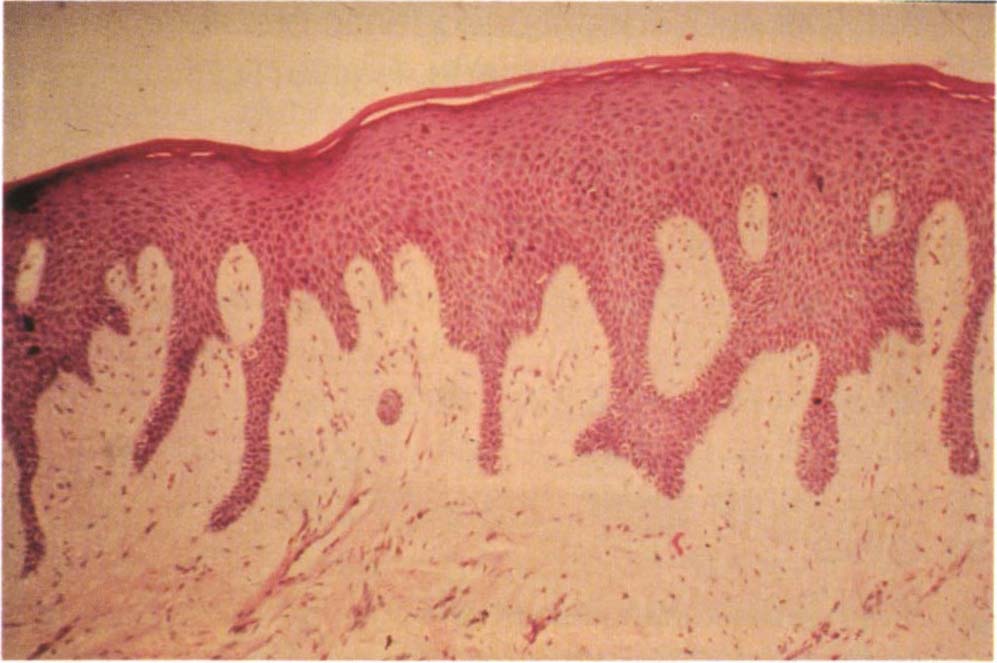

Fig. 1-1o (i) Histologic appearance of tissue from Fig. 1-1n. Note the thinning and ulceration of the epithelium and the chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. If the host resistance reduces,chronic inflammation can become acute with abscess formation.

Fig. 1-1o (ii) Histologic appearance of healthy subpontic tissue. Note the intact epithelium.

Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

The treatment of temporomandibular disorders by restorative therapy has little, if any, well controlled scientific evidence to substantiate its efficacy (see Chapter 26). Symptoms remaining or returning after such restoration can lead to patient dissatisfaction and often these patients become litigious (see Chapter 27).

A useful classification of TM disorders is:

(i) Facial Arthromyalgia28

Also termed, TMJ dysfunction syndrome, myofacial pain dysfunction syndrome – involving pain in or around the muscles of mastication (myalgia) and temporomandibular joints (arthralgia). The pain is usually described as long-standing, deep, moderate or dull and is sometimes provoked by functions such as chewing or opening. In addition, there may be limited or asymmetric mandibular movement. Like most facial pain disorders, such as trigeminal neuralgia, tension headache and migraine, the underlying mechanism is idiopathic. Many cases appear to be stress related, others have a disturbance in function which has been explained in terms of parafunction and occlusal disturbance, neither of which is supported by objective appraisal of the literature (see Chapter 26).

(ii) Internal Derangement29

This implies a disturbance in meniscus mechanics. The meniscus may be anteriorly and medially displaced with or without reduction and is usually associated with adhesion formation.

Perforations and osteophytes are rarely found. The patient may complain of clicking, irregular movement, locking or grating sounds, all of which can occur with or without joint pain.

(iii) Arthrosis and Arthritis

Arthrosis is a degenerative disorder of the joint in which joint form and structure are abnormal30. Arthritis is an inflammatory condition within the joint. Rarely occuring conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, primary and metastatic tumors may deceive the clinician.

Occlusal

Patients may be uncomfortable with their new occlusions. Some patients tolerate gross occlusal discrepancies without complaining, whereas others are intolerant to discrepancies in the range of 10 to 15 microns (see Phantom Bite page 22). Occlusal discomfort is usually perceived by the patient as:

- General discomfort with “the bite”.

- Sore teeth.

- Loose teeth or bridges.

- Sensitive teeth.

- “Tired, sore” muscles.

Tired and sore muscles are short term phenomenae and are not similar to the pain of facial arthromyalgia.

The introduction of occlusal interferences may alter the site on which existing bruxism is occuring. It must be understood that whereas some patients will be made comfortable by the correction of iatrogenic occlusal disharmonies, for those patients who have problems of psychogenic origin, such as facial arthromyalgia or phantom bite, interference with the occlusion may compound the problems.

Change in Vertical Dimension (Fig 1-1p)

The vertical dimension may be decreased as a result of severe attrition, or increased as a result of poor restorative planning. Often an increase in vertical dimension results from the use of porcelain occlusal surfaces in short clinical crown cases. The following symptoms may be elicited from the patient in response to appropriate questioning:

- Altered facial appearance, such as “my chin is too close to my nose”, or “my face is too long”, or an altered appearance of the teeth.

- Dribbling of saliva; this may occur with both increased and decreased dimensions.

- The increased creasing associated with loss of vertical dimension can more readily precipitate angular cheilitis, although not actually cause it.

- Extreme changes in vertical dimension can possibly convert an asymptomatic internal derangement into a symptomatic one. Similarly, alteration in muscle activity can precipitate myalgia (muscle pain).

- Extreme increases in the vertical dimension reduce the ability of the tongue to create a seal during swallowing. This causes a compensating movement of the larynx during swallowing, so as to maintain peripheral contact between the borders />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses