1 Introduction to Dental Anatomy

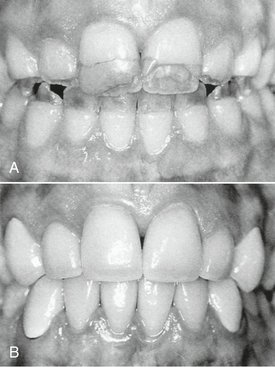

The application of dental anatomy to clinical practice can be envisioned in Figure 1-1, A where a disturbance of enamel formation (considered briefly in Chapter 2) has resulted in esthetic, psychological, and periodontal problems that may be corrected by an appropriate restorative dental treatment such as that illustrated in Figure 1-1, B. The practitioner has to have knowledge of the morphology, occlusion, esthetics, phonetics, and functions of these teeth to undertake such treatment.

Formation of the Dentitions (Overview)

The permanent, or succedaneous, teeth replace the exfoliated deciduous teeth in a sequence of eruption that exhibits some variance, an important topic that will be considered in Chapter 16.

After the shedding of the deciduous canines and molars, emergence of the permanent canines and premolars, and emergence of the second permanent molars, the permanent dentition is completed (including the roots) at about 14 to 15 years of age, except for the third molars, which are completed at 18 to 25 years of age. In effect, the duration of the permanent dentition period is 12+ years. The completed permanent dentition consists of 32 teeth if none are congenitally missing, which may be the case. The development of the teeth, dentitions, and the craniofacial complex are considered in Chapter 2. The development of occlusion for both dentitions is discussed in Chapter 16.

Nomenclature

The term mandibular refers to the lower jaw, or mandible. The term maxillary refers to the upper jaw, or maxilla. When more than one name is used in the literature to describe something, the two most commonly used names will be used initially. After that they may be combined or used separately as consistent with the literature of a particular specialty of dentistry, for example, primary or deciduous dentition, permanent or succedaneous dentition. A good case may be made for the use of both terms. By dictionary definition,1 the term primary can mean “constituting or belonging to the first stage in any process.” The term deciduous can mean “not permanent, transitory.” The same unabridged dictionary refers the reader from the definition of deciduous tooth to milk tooth, which is defined as “one of the temporary teeth of a mammal that are replaced by permanent teeth. Also called baby tooth, deciduous tooth.” The term primary can indicate a first dentition and the term deciduous can indicate that the first dentition is not permanent, but not unimportant. The term succedaneous can be used to describe a successor dentition and does not suggest permanence, whereas the term permanent suggests a permanent dentition, which may not be the case due to dental caries, periodontal diseases, and trauma. All four of these descriptive terms appear in the professional literature.

Formulae for Mammalian Teeth

The dental formula for the primary/deciduous teeth in humans is as follows:

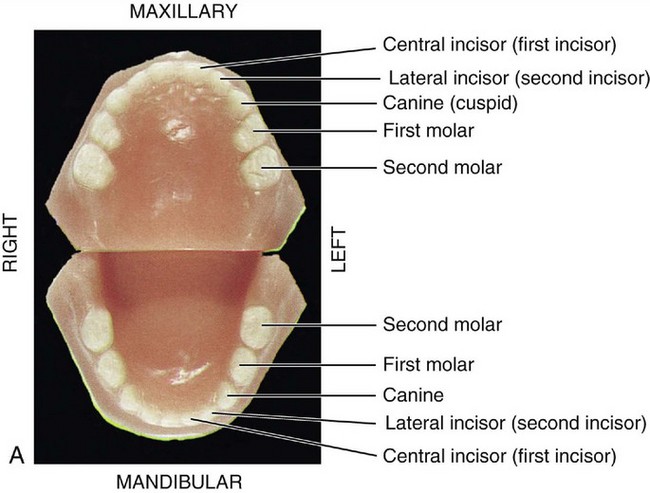

This formula should be read as: incisors, two maxillary and two mandibular; canines, one maxillary and one mandibular; molars, two maxillary and two mandibular—or 10 altogether on one side, right or left (Figure 1-2, A).

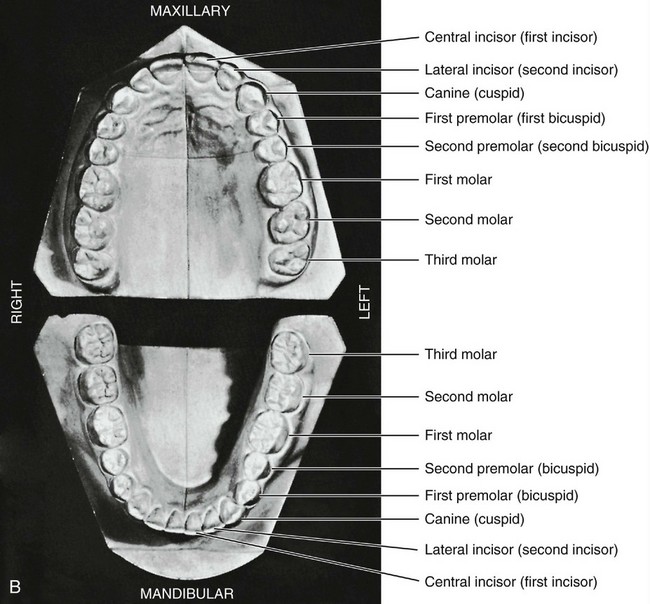

Figure 1-2 A, Casts of deciduous, or primary, dentition. B, Casts of permanent dentition.

(A from Berkovitz BK, Holland GR, Moxham BJ: Oral anatomy, histology and embryology, ed 3, St. Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

A dental formula for the permanent human dentition is as follows:

Premolars have now been added to the formula, two maxillary and two mandibular, and a third molar has been added, one maxillary and one mandibular (Figure 1-2, B).

Systems for scoring key morphological traits of the permanent dentition that are used for anthropological studies are not described here. However, a few of the morphological traits that are used in anthropological studies2 are considered in the following chapters, (e.g., shoveling, Carabelli’s trait, enamel extensions, and peg-shaped incisors). Some anthropologists use di1, di2, dc, dm1, and dm2 notations for the deciduous dentition and I1, I2, C, P1, P2, M1, M2, and M3 for the permanent teeth. These notations are generally limited to anthropological tables because of keyboard incompatibility.

Tooth Numbering Systems

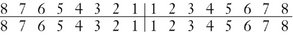

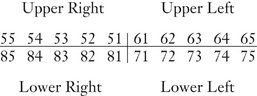

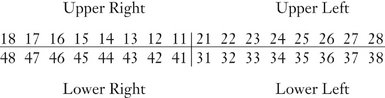

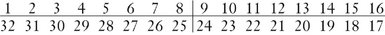

In clinical practice some “shorthand” system of tooth notation is necessary for recording data. There are several systems in use in the world, but only a few are considered here. In 1947 a committee of the American Dental Association (ADA) recommended the symbolic (Zsigmondy/Palmer) system as the numbering method of choice.3 However, because of difficulties with keyboard notation of the symbolic notation system, the ADA in 1968 officially recommended the “universal” numbering system. Because of some limitations and lack of widespread use internationally, recommendations for a change sometimes are made.4

Viktor Haderup of Denmark in 1891 devised a variant of the eight-tooth quadrant system in which plus (+) and minus (−) were used to differentiate between upper and lower quadrants and between right and left quadrants; in other words, +1 indicates the upper left central incisor and 1− indicates the lower right central incisor. Primary teeth were numbered as follows: upper right, 05+ to 01+; lower left, −01 to −05. This system is still taught in Denmark.5

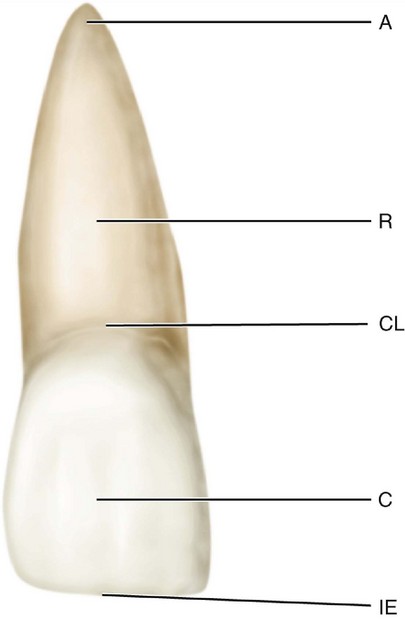

THE CROWN AND ROOT

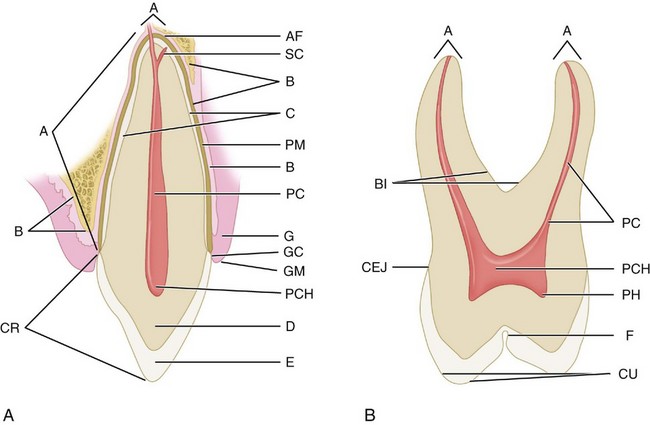

Each tooth has a crown and root portion. The crown is covered with enamel, and the root portion is covered with cementum. The crown and root join at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). This junction, also called the cervical line (Figure 1-3), is plainly visible on a specimen tooth. The main bulk of the tooth is composed of dentin, which is clear in a cross section of the tooth. This cross section displays a pulp chamber and a pulp canal, which normally contain the pulp tissue. The pulp chamber is in the crown portion mainly, and the pulp canal is in the root (Figure 1-4).The spaces are continuous with each other and are spoken of collectively as the pulp cavity.

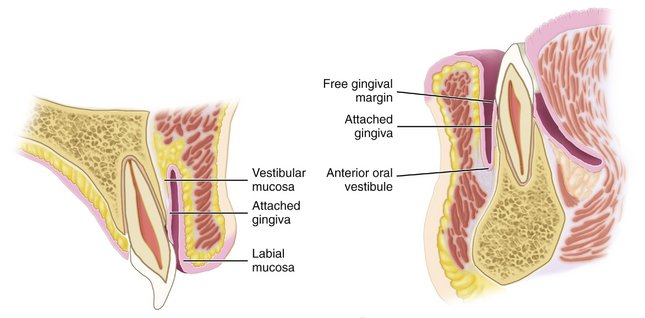

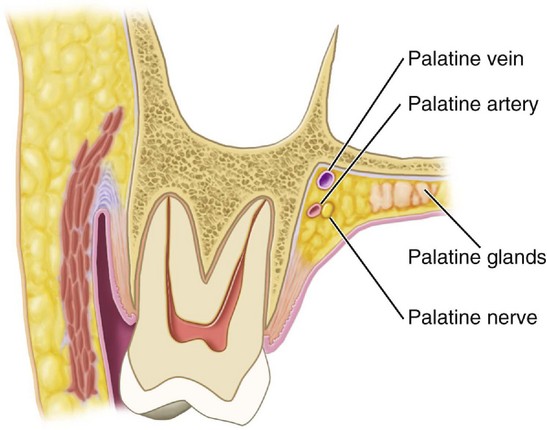

The four tooth tissues are enamel, cementum, dentin, and pulp. The first three are known as hard tissues, the last as soft tissue. The pulp tissue furnishes the blood and nerve supply to the tooth. The tissues of the teeth must be considered in relation to the other tissues of the orofacial structures (Figures 1-5 and 1-6) if the physiology of the teeth is to be understood.

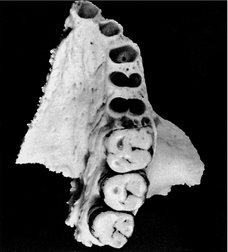

The root portion of the tooth is firmly fixed in the bony process of the jaw, so that each tooth is held in its position relative to the others in the dental arch. That portion of the jaw serving as support for the tooth is called the alveolar process. The bone of the tooth socket is called the alveolus (plural, alveoli) (Figure 1-7).

SURFACES AND RIDGES

The crowns of the incisors and canines have four surfaces and a ridge, and the crowns of the premolars and molars have five surfaces. The surfaces are named according to their positions and uses (Figure 1-8). In the incisors and canines, the surfaces toward the lips are called labial surfaces; in the premolars and molars, those facing the cheek are the buccal surfaces. When labial and buccal />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

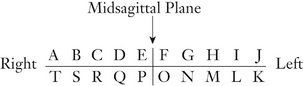

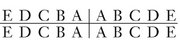

. For the mandibular left central incisor, the notation is given as

. For the mandibular left central incisor, the notation is given as  . This numbering system presents difficulty when an appropriate font is not available for keyboard recording of Zsigmondy/Palmer symbolic notations. For simplification this symbolic notation is often designated as Palmer’s dental notation rather than Zsigmondy/Palmer notation.

. This numbering system presents difficulty when an appropriate font is not available for keyboard recording of Zsigmondy/Palmer symbolic notations. For simplification this symbolic notation is often designated as Palmer’s dental notation rather than Zsigmondy/Palmer notation.

, and the left mandibular central incisor as

, and the left mandibular central incisor as  . The Palmer notation for the entire permanent dentition is as follows:

. The Palmer notation for the entire permanent dentition is as follows: