Craniofacial Anomalies

Carol Anne Murdoch-Kinch

Developmental disturbances can affect the normal growth and differentiation of craniofacial structures. As a consequence, they are usually first discovered in infancy or childhood. Many of the conditions discussed in this chapter have an unknown etiology. Some are caused by known and recently discovered genetic mutations, whereas others result from environmental factors. These conditions result in a variety of abnormalities of the face and jaws, including abnormalities of structure, shape, organization, and function of hard and soft tissues. A multitude of conditions affect the morphogenesis of the face and jaws, many of which are rare syndromes. This chapter briefly reviews more common developmental abnormalities that may be encountered in dental practice.

Cleft Lip and Palate

Disease Mechanism

A failure of fusion of the developmental processes of the face during fetal development may result in a variety of facial clefts. Cleft lip and cleft palate are the most common developmental craniofacial anomalies. Their incidence varies with geographic location, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. In white populations, the incidence of cleft lip is 1 : 800 to 1 : 1000 live births, and the incidence of cleft palate is approximately 1 : 1000. Cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) and cleft palate are two different conditions with different etiologies. CL/P results from a failure of fusion of the medial nasal process with the maxillary process. This condition can range in severity from a unilateral cleft lip to bilateral complete clefting through the lip, alveolus, and hard and soft palate in the most severe cases. Cleft palate develops from a failure of fusion of the lateral palatal shelves. The minimal manifestation of cleft palate is a submucous cleft in which the palate appears to be intact except for notching of the uvula (bifid uvula) or notching in the posterior border of the hard palate detectable by palpation. The most severe presentation is complete clefting of the hard and soft palate. The precise etiology of orofacial clefting is not completely understood. However, most cases of CL/P and cleft palate are considered to be multifactorial with a strong genetic component. CL/P and cleft palate each can be associated with other abnormalities, as part of a genetic malformation syndrome, such as 22q.11 deletion syndrome (velocardiofacial syndrome—cleft palate and facial and cardiac abnormalities) or van der Woude syndrome (cleft lip or cleft palate or both and lip pits). Other factors that are implicated in the development of orofacial clefts include nutritional disturbances (prenatal folate deficiency); environmental teratogenic agents (maternal smoking, in utero exposure to anticonvulsants); stress, which results in increased secretion of hydrocortisone; defects of vascular supply to the involved region; and mechanical interference with the fusion of the embryonic processes (cleft palate in Pierre Robin sequence). Clefts involving the lower lip and mandible are extremely rare.

Clinical Features

The frequency of CL/P and cleft palate varies with gender and race, but in general CL/P is more common in males, whereas cleft palate is more common in females. Both conditions are more common in Asians and Hispanics than African Americans or Caucasians. The severity of CL/P varies from a notch in the upper lip, to a cleft involving only the lip, to extension into the nostril resulting in deformity of the ala of the nose. As CL/P increases in severity, the cleft includes the alveolar process and palate. Bilateral cleft lip is more frequently associated with cleft palate. Cleft palate also varies in severity, ranging from involvement of only the uvula or soft palate to extension all the way through the palate to include the alveolar process in the region of the lateral incisor on one or both sides. With involvement of the alveolar process, there is an increase in frequency of dental anomalies in the region of the cleft, including missing, hypoplastic, and supernumerary teeth and enamel hypoplasia. Dental anomalies are also more prevalent in the mandible in these patients. In both CL/P and cleft palate, the palatal defects interfere with speech and swallowing. Affected individuals with palatal clefts are also at increased risk for recurrent middle ear infections because of the abnormal anatomy and function of the eustachian tube.

Imaging Features

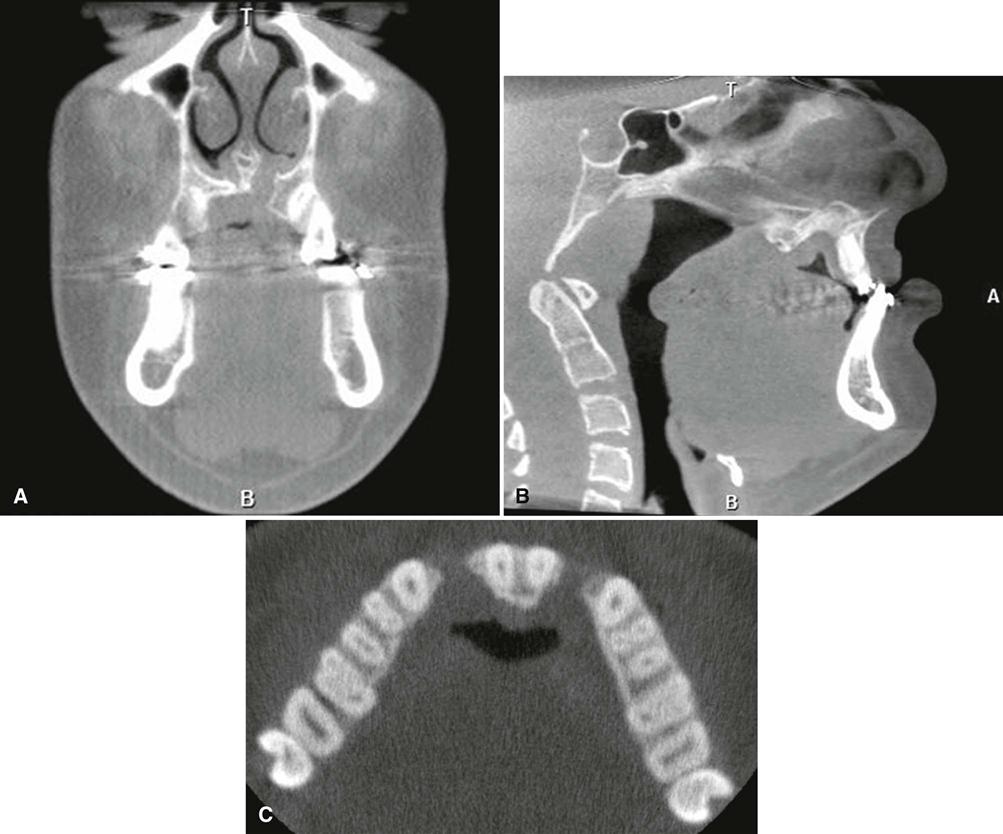

The typical imaging appearance is a well-defined vertical radiolucent defect in the alveolar bone and numerous associated dental anomalies (Figs. 32-1 and 32-2). These anomalies may include the absence of the maxillary lateral incisor and the presence of supernumerary teeth in this region. The involved teeth often are malformed and poorly positioned. In patients with cleft lip and palate, there may be a mild delay in the development of maxillary and mandibular teeth and an increased incidence of hypodontia in both arches. The osseous defect may extend to include the floor of the nasal cavity. In patients with a repaired cleft, a well-defined osseous defect may not be apparent but only a vertically short alveolar process at the cleft site.

Management

Management of CL/P and cleft palate is complex, requiring the coordinated efforts of a multidisciplinary team known as a cleft palate/craniofacial anomalies team. This team usually includes a plastic and reconstructive surgeon; oral and maxillofacial surgeon; ear, nose, and throat surgeon; orthodontist; dentist; speech therapist; psychologist; nutritionist; and social worker. Clefts of the palate are usually surgically repaired within the first year of life, whereas clefts of the lip are usually repaired within the first 3 months to aid in feeding and maternal-infant bonding. The bone in the cleft site is often augmented with bone grafting before replacement of missing teeth with either fixed or removable prosthodontics or dental implants. Orthodontic treatment is usually necessary to recreate a normal arch form and functional occlusion.

Crouzon Syndrome

Synonyms

Synonyms for Crouzon syndrome include craniofacial dysostosis, syndromic craniosynostosis, and premature craniosynostosis.

Disease Mechanism

Crouzon syndrome is an autosomal dominant skeletal dysplasia characterized by variable expressivity and almost complete penetrance. It is one of many diseases characterized by premature craniosynostosis (closure of cranial sutures). Its incidence is estimated at 1 : 25,000 births. Of these cases, 33% to 56% may arise as a consequence of spontaneous mutations, with the remaining being familial. Crouzon syndrome is caused by a mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor II on chromosome 10. Mutations at this site are also responsible for other craniosynostosis syndromes with similar facial features but clinically visible limb abnormalities. In patients with Crouzon syndrome, the coronal suture usually closes first, and eventually all cranial sutures close early. There is also premature fusion of the synchondroses of the cranial base. The subsequent lack of bone growth perpendicular to the synchondroses and cranial coronal sutures produces the characteristic cranial shape and facial features.

Clinical Features

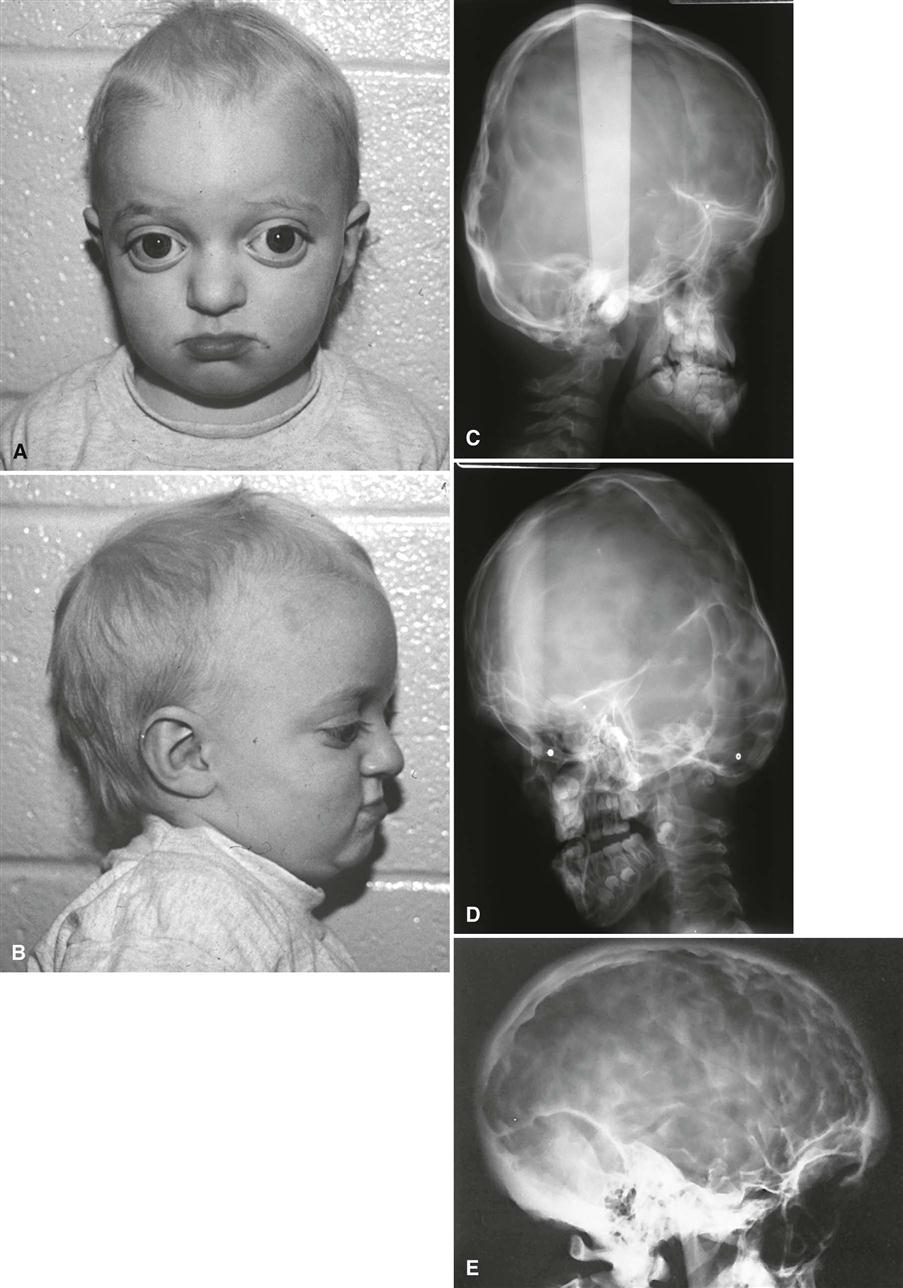

Patients characteristically have brachycephaly (short skull front to back), hypertelorism (increased distance between eyes), and orbital proptosis (protruding eyes) (Fig. 32-3, A and B). In familial cases, the minimal criteria for diagnosis are hypertelorism and orbital proptosis. Patients may become blind as a result of early suture closure and increased intracranial pressure. The nose often appears prominent and pointed because the maxilla is narrow and short in a vertical and anteroposterior dimension. The anterior nasal spine is hypoplastic and retruded, failing to provide adequate support to the soft tissue of the nose. The palatal vault is high, and the maxillary arch is narrow and retruded, resulting in crowding of the dentition.

Imaging Features

The earliest radiographic signs of cranial suture synostosis are sclerosis and overlapping edges. Sutures that normally should look radiolucent on the skull film are not detectable or show sclerotic changes. Rarely, the facial features may manifest before evidence of sutural synostosis. Premature fusion of the cranial base leads to diminished facial growth. In some cases, prominent cranial markings are noted, which are also seen in normal growing patients, but are more prominent because of an increase in intracranial pressure from the growing brain. These markings may be seen as multiple radiolucencies appearing as depressions (so-called digital impressions) of the inner surface of the cranial vault, which results in a beaten metal appearance (Fig. 32-3, C-E).

In the jaws, the lack of growth in an anteroposterior direction at the cranial base results in maxillary hypoplasia, creating a class III malocclusion in some patients. The maxillary hypoplasia contributes to the characteristic orbital proptosis because the maxilla forms part of the inferior orbital rim and, if severely hypoplastic, fails to support the orbital contents adequately. The mandible is typically smaller than normal but appears prognathic in relation to the severely hypoplastic maxilla.

Differential Diagnosis

Premature craniosynostosis, either isolated or as part of a genetic syndrome, is a common disorder. The incidence of Crouzon syndrome is reported to range from 1 : 2100 to 1 : 2500 births. Other causes of craniosynostosis must be differentiated from Crouzon syndrome, including other syndromic forms of craniosynostosis and nonsyndromic coronal craniosynostosis. The characteristic facial features must be present to suggest Crouzon syndrome.

Management

The craniofacial features of Crouzon syndrome worsen over time because of the abnormal craniofacial growth. Early diagnosis permits surgical and orthodontic treatment from infancy through adolescence, coordinated by a cleft palate/craniofacial anomalies team. The objectives of these treatments are to allow normal brain growth and development by preventing increased intracranial pressure, protect the eyes by providing adequate bony support, and improve facial esthetics and occlusal function. Because of early diagnosis and improvements in medical and dental care, most patients have normal intelligence and good functional outcomes and can expect a normal life span.

Hemifacial Microsomia

Synonyms

Synonyms for hemifacial microsomia include hemifacial hypoplasia, craniofacial microsomia, lateral facial dysplasia, Goldenhar syndrome, and oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (OAV) spectrum.

Disease Mechanism

Hemifacial microsomia is the second most common developmental craniofacial anomaly after cleft lip and palate and affects approximately 1 : 56,000 live births. Hemifacial microsomia is a feature of Goldenhar syndrome. This syndrome can also include a broader array of anomalies within the oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (OAV) complex. Patients with hemifacial microsomia typically display reduced growth and development of half of the face owing to abnormal development of the first and second branchial arches. This malformation sequence is usually unilateral but occasionally may involve both sides (craniofacial microsomia). When the whole side of the face is involved, the mandible, maxilla, zygoma, external and middle ear, hyoid bone, parotid gland, vertebrae, fifth and seventh cranial nerves, musculature, and other soft tissues are diminished in size and sometimes fail to develop. Delayed dental eruption and hypodontia on the affected side also have been reported. Most cases occur spontaneously, but familial cases demonstrating autosomal dominant inheritance have been reported. There is a male predominance of 3 : 2 and a right-side predominance of 3 : 2. Cases have been reported with epibulbar dermoids, preauricular skin appendages, and preauricular fistulas; additional vertebral anomalies; and cardiac, cerebral, and renal malformations (Goldenhar syndrome and OAV complex). Genetic mutations at chromosome 14q32 and microdeletions at 22q11 have been associated with some cases of Goldenhar syndrome; however, in most cases, a clear genetic cause is not found.

Clinical Features

Hemifacial microsomia is usually apparent at birth. Patients with this condition have a striking appearance caused by progressive failure of the affected side to grow, which gives the involved side of the face a reduced dimension. In addition, aplasia or hypoplasia of the external ear (microtia) is common, and the ear canal is often missing. In some patients, the skull is diminished in size. In about 90% of cases, there is malocclusion on the affected side. The midsagittal plane of the patient’s face is curved toward the affected side. The occlusal plane often is canted up to the affected side.

Imaging Features

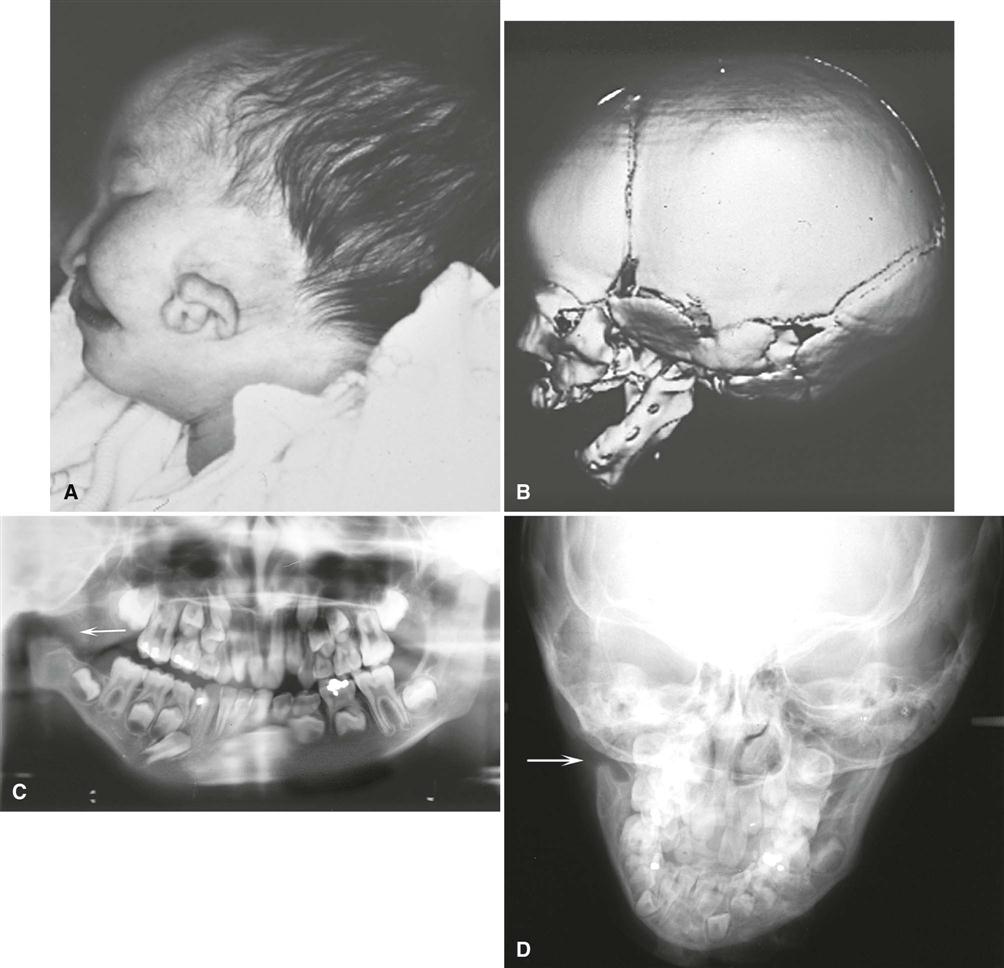

The primary radiographic finding is a reduction in the size of the bones on the affected side. This change is clearest in the mandible, which may show a reduction in the size of or, in severe cases, lack of any development of the condyle, coronoid process, or ramus. The body is reduced in size, and a portion of the distal aspect may be missing (Fig. 32-4). The dentition on the affected side may show a reduction in the number or size of the teeth. Multidetector computed tomographic (MDCT) examination shows a reduction in the size of the muscles of mastication and muscles of facial expression and hypoplasia or atresia of the auditory canal and ossicles of the middle ear. The course of the facial nerve is often shown to be abnormal on MDCT examination of the temporal bone. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be useful in demonstrating the extent of inner ear abnormalities and involvement of the facial nerve and other soft tissues of the mouth and eyes. Thin section MDCT imaging of the temporal bone is often performed to assess the degrees of stenosis of the external auditory meatus and middle and inner ear malformations to plan treatment, including the use of cochlear implants, bone-anchored hearing aids, or implant-retained ear prostheses. This imaging is particularly important for patients with Goldenhar syndrome and the broader OAV complex. A multimodality approach to imaging can be optimal, including panoramic images to demonstrate dental development, cephalometric images and cone-beam CT (CBCT) imaging to assess the facial asymmetry and plan orthodontic treatment, two-dimensional CT imaging of the temporal bones to assess the external and internal ear anatomy, and three-dimensional CT imaging for surgical treatment planning.

Differential Diagnosis

The features of hemifacial microsomia are characteristic. Condylar hypoplasia, especially caused by a fracture at birth or by juvenile arthrosis (Boering’s arthrosis), may be similar, but it does not produce the ear changes. Exposure of the face of a child to radiation therapy during growth also may result in underdevelopment of the irradiated tissues. In progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry-Romberg synd/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses