Chronic Periodontitis

Chronic periodontitis has been defined as “an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth, progressive attachment loss, and bone loss.”18 This definition outlines the major clinical and etiologic characteristics of the disease: (1) microbial biofilm formation (dental plaque); (2) periodontal inflammation (e.g., gingival swelling, bleeding on probing); and (3) attachment as well as alveolar bone loss.

In addition to the local immune response caused by the dental biofilm, periodontitis may also be associated with a number of systemic disorders and defined syndromes. In most cases, patients with systemic diseases that lead to impaired host immunity may also show periodontal destruction. Therefore, periodontitis is a disease that is not only limited to the area of the oral cavity; it is also associated with severe systemic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disorders, diabetes mellitus).40

Clinical Features

General Characteristics

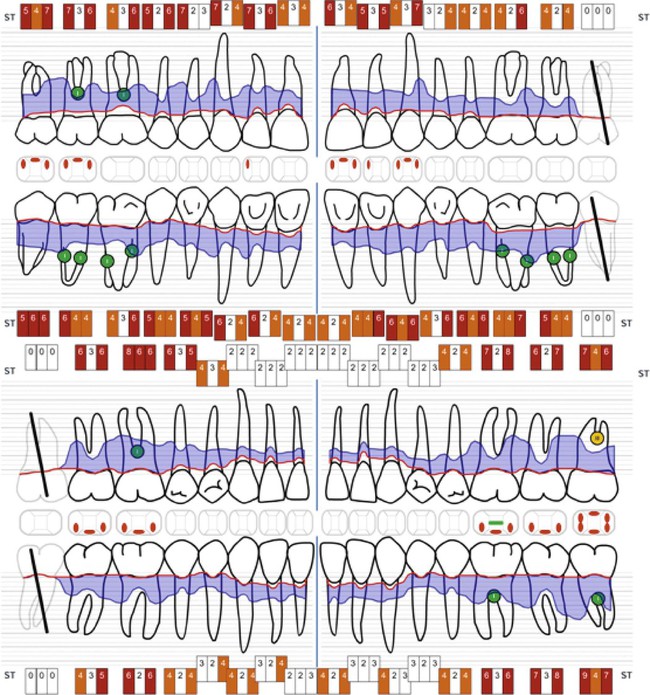

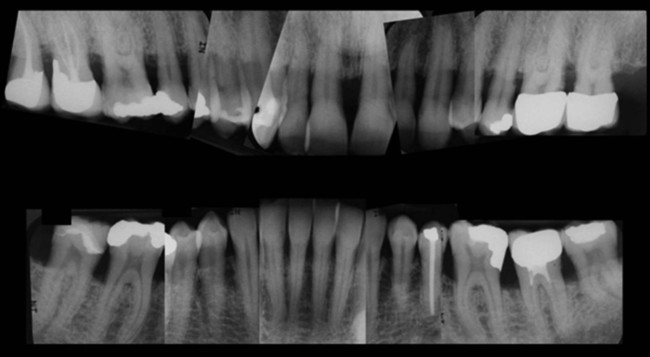

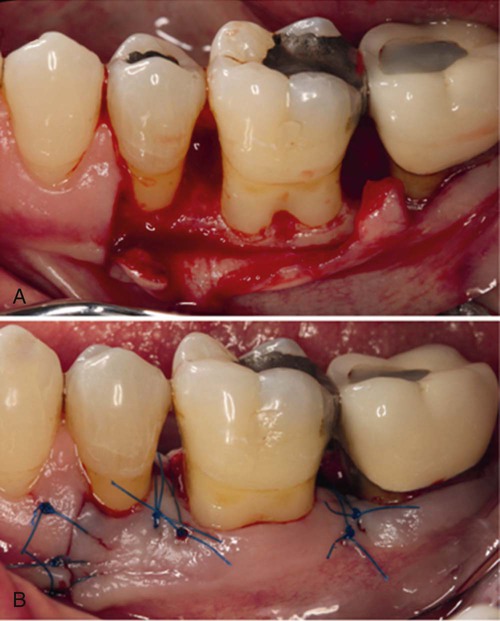

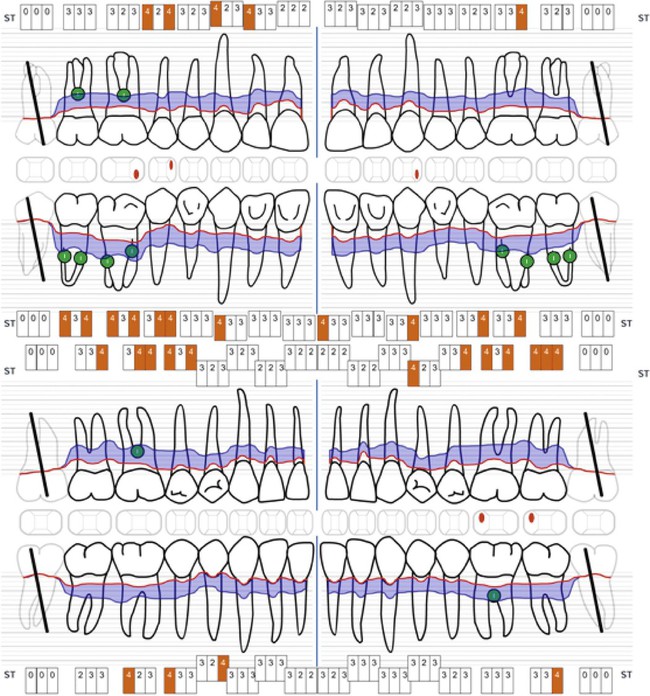

Characteristic clinical findings in patients with untreated chronic periodontitis include the following (see also the case presentation in Figures 23-1 through 23-6):

• Supragingival and subgingival plaque and calculus

• Gingival swelling, redness, and loss of gingival stippling

• Altered gingival margins (e.g., rolled, flattened, cratered papillae, recessions)

• Attachment loss (angular or horizontally)

Chronic periodontitis can be clinically revealed with periodontal screening and recording, which results in a periodontal screening index rating. The condition is diagnosed via the assessment of the clinical attachment level and the detection of inflammatory changes in the marginal gingiva (see Figure 23-1). Measurements of periodontal pocket depth in combination with the location of the marginal gingiva allow for conclusions to be drawn regarding the loss of clinical attachment (see Figures 23-2 and 23-6). Dental radiographs display the extent of bone loss, which is indicated by the distance between the cementoenamel junction and the alveolar bone crest (see Figure 23-3). The distinction between aggressive and chronic periodontitis is sometimes difficult, because the clinical features may be similar at the time of the first examination. At later time points during treatment, aggressive and chronic periodontitis may be differentiated by the rate of disease progression over time, the familial nature of aggressive disease, the disease’s resistance to periodontal anti-infective therapy, and the presence of local factors.

Disease Severity

The severity of periodontal destruction that occurs as a result of chronic periodontitis is generally considered a function of time in combination with systemic disorders that impair or enhance host immune responses. With increasing age, attachment loss and bone loss become more prevalent and more severe as a result of an accumulation of destruction. Disease severity may be described as mild, moderate, or severe (see Chapter 4):

Disease Progression

Chronic periodontitis does not progress at an equal rate in all affected sites throughout the mouth. Some involved areas may remain static for long periods,33 whereas others may progress more rapidly. More rapidly progressive lesions occur most frequently in interproximal areas,32,34 and they may also be associated with areas of greater plaque accumulation and inaccessibility to plaque-control measures (e.g., furcation areas, overhanging margins of restorations, sites of malposed teeth, areas of food impaction).

Further factors that influence disease progression may be of systemic origin. Patients with poorly adjusted diabetes mellitus show a significantly higher risk of developing a severe progression of chronic periodontitis.43,61

Several models have been proposed to describe the rate of disease progression.57 In these models, progression is measured by determining the amount of attachment loss during a given period as follows:

• The continuous model suggests that disease progression is slow and continuous, with affected sites showing a constantly progressive rate of destruction throughout the duration of the disease.

• The random or episodic-burst model proposes that periodontal disease progresses by short bursts of destruction followed by periods of no destruction. This pattern of disease is random with respect to the tooth sites affected and the chronology of the disease process.

• The asynchronous, multiple-burst model of disease progression suggests that periodontal destruction occurs around affected teeth during defined periods of life and that these bursts of activity are interspersed with periods of inactivity or remission. The chronology of these bursts of disease is asynchronous for individual teeth or groups of teeth.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses