When a patient has an impacted tooth, the timing of orthodontic treatment, the type of surgical procedure to expose the tooth, the orthodontic mechanics, and the potential problems vary depending on which tooth is impacted and its position in the jaw. This case report describes the successful treatment of a patient with a horizontally impacted mandibular canine. The impacted tooth was surgically exposed and then moved into its normal position in the dental arch, combined with correction of a Class II Division 1 malocclusion.

Most permanent teeth erupt into occlusion. In some people, however, a permanent tooth fails to erupt and becomes impacted in the alveolus. This problem has several solutions. The impacted tooth could be extracted, an autotransplantation could be performed, or the tooth could be surgically exposed and moved into the dental arch orthodontically. The timing of orthodontic treatment, the type of surgical procedure to expose the impacted tooth, the necessary orthodontic mechanics, and potential problems with treatment vary depending on which tooth is impacted and its position in the jaw. This case report describes the treatment of a horizontally impacted mandibular canine.

Diagnosis

A girl, aged 11 years 4 months, had chief complaints of crowding of the maxillary anterior teeth and an excessive overjet. Apart from a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy at the age of 4 years, her medical history and temporomandibular joint function were normal.

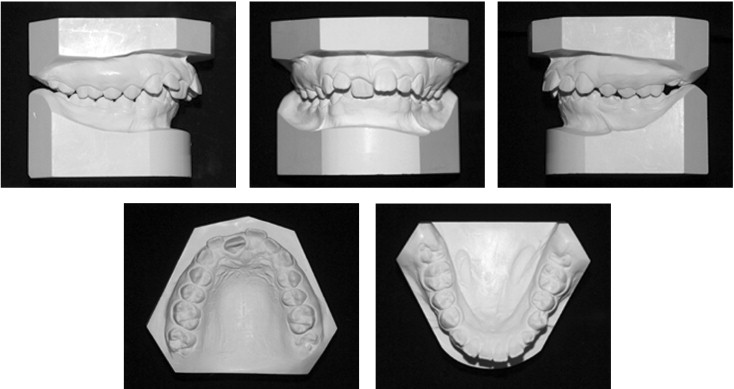

The pretreatment facial photographs showed a convex facial profile caused by a retruded mandible ( Fig 1 ). The pretreatment intraoral photographs and dental casts showed a Class II Division 1 malocclusion, with a full premolar width distoclusion of the molars and canines on both sides ( Figs 1 and 2 ). The patient had a deep overbite, with the mandibular incisors touching the palatal mucosa. She had a midline shift of 1 or 2 mm of the mandibular teeth to the right. The maxillary right central incisor was retroclined, probably caused by trauma to the deciduous right central incisor at age 2.5 years. The tooth was broken and, after an infection, was extracted by the patient’s dentist. Except for the third molars and the mandibular left canine, all other teeth were present. The mandibular left deciduous canine was still present. Apart from habitual lip biting, the patient had no functionalproblems.

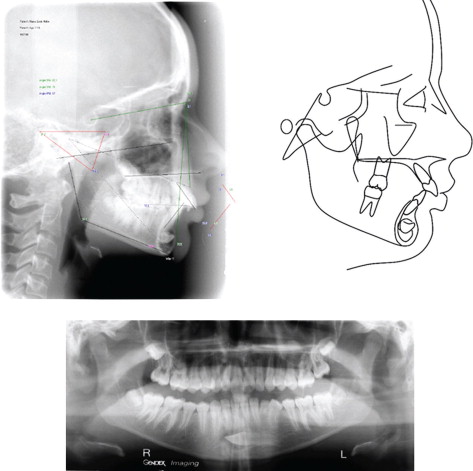

The pretreatment lateral cephalometric and panoramic radiographs showed impacted third molars and a horizontally impacted mandibular left canine, apical and labial of the apices of the mandibular anterior teeth in the chin region ( Fig 3 ). The canine was completely covered with bone. The root of the mandibular left deciduous canine was almost completely resorbed. Cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal Class II relationship (ANB angle, 8.1°) with a normal mandibular plane angle (SN-GoGn, 31.9°), a retrognathic mandible (SNB angle, 74°), proclination of the maxillary incisors (+1 to NA, 33°) and mandibular incisors (−1 to NB, 32.5°), and an interincisal angle of 106.4° ( Fig 3 , Table ). The other cephalometric values were within 1 SD of normal.

| Measurement | Norm | Pretreatment (11 y 4 mo) | Posttreatment (15 y 0 mo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 82 | 82.1 | 79 |

| SNB (°) | 80 | 74 | 76.5 |

| ANB (°) | 2 | 8.1 | 2.5 |

| Pogonion to NB (mm) | 4 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Occlusal plane to sN (°) | 14 | 12.3 | 15.7 |

| SN to GoGn (°) | 32 | 31.9 | 31.2 |

| Maxillary incisor to Na (°) | 22 | 33 | 35.7 |

| Maxillary incisor to Na (mm) | 4 | 3.5 | 8.2 |

| Mandibular incisor to NB (°) | 25 | 32.5 | 34.3 |

| Mandibular incisor to NB (mm) | 4 | 5.9 | 8.7 |

| Interincisal angle (°) | 131 | 106.4 | 107.5 |

The patient was diagnosed with a Class II Division 1 malocclusion, a retrognathic mandible, a deep overbite, a retroclined maxillary right central incisor, a severely impacted mandibular left canine, and impacted third molars. She and her parents requested correction of the malalignment of the maxillary anterior teeth and reduction of the overjet.

Etiology

Our knowledge about the prevalence and etiology of impactions has grown. Impactions in general are twice as often seen in white people compared with people of Asiatic origin, and 3 times more often in female patients. Third molars are the most frequently impacted teeth, followed by maxillary canines, mandibular premolars, and maxillary central incisors. Mandibular canines appear to be impacted less often than maxillary canines. The reported frequencies of mandibular canine impaction range from 0.05% to 0.4%. The position of the tooth bud for some reason might be such thatthe root develops in a horizontal direction. The canine then becomes impacted horizontally in a labial position below the apices of the incisors and, with the crown positioned mesially, often crosses the midline. In these situations, it is difficult to correct the impaction. In this patient, the radiographs clearly show the exact location of the canine ( Fig 3 ).

Etiology

Our knowledge about the prevalence and etiology of impactions has grown. Impactions in general are twice as often seen in white people compared with people of Asiatic origin, and 3 times more often in female patients. Third molars are the most frequently impacted teeth, followed by maxillary canines, mandibular premolars, and maxillary central incisors. Mandibular canines appear to be impacted less often than maxillary canines. The reported frequencies of mandibular canine impaction range from 0.05% to 0.4%. The position of the tooth bud for some reason might be such thatthe root develops in a horizontal direction. The canine then becomes impacted horizontally in a labial position below the apices of the incisors and, with the crown positioned mesially, often crosses the midline. In these situations, it is difficult to correct the impaction. In this patient, the radiographs clearly show the exact location of the canine ( Fig 3 ).

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives, based on the cephalometric and dental-cast analysis, were to correct the retruded position of the mandible, the deep overbite, and the malalignment of the maxillary anterior teeth; achieve bilateral Class I canine and molar occlusion; and improve facial balance. In addition, a solution was needed for the impaction of the mandibular left canine combined with the severely resorbed root of the deciduous canine.

Treatment alternatives

For the impacted mandibular left canine, several treatment alternatives were available.

One could choose surgical removal of the impacted tooth, while preserving the deciduous canine as long as possible. This patient had a diastema mesial and distal to the retained tooth, so a composite buildup could achieve the mesiodistal width of a normal canine already at the start of treatment. During the fixed appliance treatment phase, this tooth would have to be left out to prevent further resorption of its root. After the fixed appliance phase, the vertical dimension of this tooth could be restored with a composite buildup. For the long-term preservation of this tooth, one should not create canine-guided occlusion on the left side but take care that this tooth is out of occlusion during lateral excursive movements of the mandible. However, long-term preservation of a deciduous tooth is not realistic.

Short-term loss of this tooth would require prosthetic replacement with a resin-bonded bridge. A long-term solution would be a conventional bridge. If the tooth held for several years with preservation of thebone, an implant could be placed. However, because of the amount of root resorption at the start of treatment, a short survival was a more realistic approach than long-term preservation of the deciduous canine. A resin-bonded bridge could cover the time gap between loss of the deciduous canine and placing of the implant. Disadvantages included the irreversible tooth preparation that is required and the uncertain longevity of this type of prosthesis. The survival rate is only 60% after 10 years. Conventional fixed bridges have a median lifetime of about 20 years. In adolescents, preparationof the abutment teeth might need to be delayed because of pulpsize.

Autotransplantation, possibly followed by immediate or postponed endodontic treatment of the mandibular left canine, was another option. Root formation of the mandibular canine was nearly or fully completed. When mature teeth are transplanted, either postponed endodontic treatment is carried out or revascularization is anticipated. According to Andreasen, the 5-year survival rates for canines with complete root formation are 82% for tooth survival, 22% for pulpal healing, and 48% for periodontal ligament healing. A disadvantage of this solution is that the tooth eventually might become ankylosed. However, with this treatment approach, one could expect survival of the canine until the patient is old enough for an implant to be placed without the need for bone augmentation.

The last treatment option was surgical exposure followed by movement of the canine toward its normal position in the dental arch. With the oral surgeon, the parents, and the patient, it was decided to surgically expose the mandibular left canine, place a button and a ligature on it during surgery, close the wound, and start moving the canine to its normal position.

Correction of a Class II molar occlusion is possible with headgear, functional appliance, or extraction of the maxillary premolars and retraction of the anterior teeth with fixed appliances. Since the upper part of the face was well balanced and the lower jaw was clearly retruded, a functional appliance to bring the mandible forward was the preferred method of treatment.

Erupting the mandibular left canine into its normal position in the arch was considered the most time-consuming part of the treatment. Total treatment time would be shortened with an appliance that would make this possible from the start of treatment. For this reason, it was decided not to use a bionator or functional appliance but, rather, a Herbst appliance combined with a fixed appliance on the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. This would permit achieving all treatment goals simultaneously from the start of treatment and, therefore, shortening the total treatment time.

A Herbst appliance sometimes causes proclination of the mandibular incisors. In this patient, this could reduce the possibility of mandibular incisor root resorption. If for some reason treatment did not work out as hoped, we could still adjust the treatment strategy and attempt autotransplantation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses