Introduction

The aim of this prospective clinical study was to investigate the cephalometric changes produced by bonded spurs associated with high-pull chincup therapy in children with Angle Class I malocclusion and anterior open bite.

Methods

Thirty patients with an initial mean age of 8.14 years and a mean anterior open bite of −3.93 mm were treated with bonded spurs associated with chincup therapy for 12 months. An untreated control group of 30 subjects with an initial mean age of 8.36 years and a mean anterior open bite of −3.93 mm and the same malocclusion was followed for 12 months for comparison. Student t tests were used for intergroup comparisons.

Results

The treated group demonstrated a significantly greater decrease of the gonial angle, and increase in overbite, palatal tipping of the maxillary incisors, and vertical dentoalveolar development of the maxillary and mandibular incisors compared with the control group.

Conclusions

The association of bonded spurs with high-pull chincup therapy was efficient for the correction of the open bite in 86.7% of the patients, with a 5.23-mm (SD, ±1.69) overbite increase.

The prevalence of anterior open bite in the mixed dentition is 17.7%, and the etiology is multifactorial, including oral habits, abnormal size or function of the tongue, oral breathing, vertical growth pattern, and congenital or acquired diseases. Among the most frequent habits are finger sucking, pacifiers, altered labial postures, and tongue habits.

Several treatments have been proposed to correct this malocclusion. Although many treatment modalities are available, effectiveness and stability after treatment are still critical issues because evidence on long-term stability of these options is lacking.

Many authors have emphasized that a skeletal open bite should be treated early in the mixed dentition. The spurs might be an excellent treatment option to allow normal development of the anterior dentoalveolar region, since they prevent thumb or dummy sucking, tongue thrusting, and anterior tongue rest posture. For a long time, they were considered extremely traumatic and dropped for fear of provoking psychologic problems and alienating parents and patients. However, it has already been concluded that no psychologic problems arose from using spurs, and this appliance was considered the most effective means for arresting finger habits and correcting an anterior open bite. Recently, Nogueira et al developed the Nogueira lingual bonded spurs (3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) based on the principles of traditional spurs. This appliance has some apparent advantages, such as small size (about 3 mm), low cost, esthetics, no laboratory preparation, easy installation, and reduced clinical time for bonding (about 2 minutes per spur). No study with bonded spur appliances was found.

Although some studies have concluded that most subjects with a high angle malocclusion have a normal overbite, or even a deep bite, from a compensatory eruption mechanism, others suggest that most cases of anterior open bite are related to a long face pattern with an increase in lower anterior face height and clockwise mandibular rotation. In these patients, dental compensations produced by conventional orthodontic treatment might not lead to satisfactory outcomes, thus requiring another treatment approach directed at vertical control of facial growth. Chincup therapy is indicated by some authors for vertical control of the anterior open bite. Furthermore, no study associating the chincup with bonded spurs appliance was found.

Therefore, the aim of this prospective clinical study was to cephalometrically analyze the dentoalveolar and skeletal changes produced by bonded spurs associated with high-pull chincup therapy in children with Angle Class I anterior open-bite malocclusions treated for 12 months.

Material and methods

The sample size of each group was calculated based on an alpha significance level of 0.05 and a beta of 0.2 to achieve power of 80% to detect a mean difference of 1.5 mm between the groups, with an estimated standard deviation of 1.73 mm, according to Pedrin et al. The sample size calculation showed that 22 patients in each group were needed. The sample size of this study comprised 30 patients in each group.

To obtain 30 patients of both sexes for the treated group, 1 operator (M.A.C.) examined 1482 subjects in the city of Bauru, São Paulo, Brazil, under written authorization of their parents and school supervisors. The subjects were consecutively selected according to the following criteria: children between 6 and 10 years of age with Angle Class I malocclusions, anterior open bite equal to or greater than 1 mm, and the maxillary and mandibular permanent central incisors fully erupted. Full eruption in young children is difficult to determine. Therefore, children in the first transition period were considered to be eligible for treatment when the maxillary lateral incisors were beginning to erupt and the maxillary central incisors still showed an open bite. Children with tooth agenesis, loss of permanent teeth, crowding, maxillary constriction, or posterior crossbites were excluded from this stu dy. Oral habits were not evaluated. The treated group consisted of 30 patients with Angle Class I malocclusion with initial mean anterior open bite of −3.93 mm. All patients were treated by 1 operator (M.A.C.) under a senior supervisor.

The control group consisted of 30 untreated patients with Angle Class I malocclusion with an initial mean anterior open bite of −3.93 mm obtained from the files of the orthodontic department at the University of São Paulo, Bauru Dental School, Brazil ( Table I ). This sample had no treatment and was previously selected according to the same criteria as above. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents, allowing their children to participate in this research. This research project was approved by the ethics committee of the University of São Paulo, Bauru Dental School, Brazil. The initial mean cephalometric characteristics of both groups are shown in Table II . At the pretreatment stage, both groups were at stage 1 of cervical vertebrae maturation, which is the period before the peak in skeletal maturity, according to the classification of Baccetti et al.

| Group | Treated group | Control group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Initial age (y) | 8.14 | 0.73 | 8.36 | 1.05 | 0.35 |

| Final age (y) | 9.14 | 0.73 | 9.36 | 1.05 | 0.35 |

| Variable | n | Boys | Girls | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated group | |||||||

| SN.GoGn (°) | 30 | 9 | 21 | 34.55 | 5.61 | 24.40 | 47.70 |

| ANB (°) | 30 | 9 | 21 | 5.01 | 1.98 | 1.20 | 10.0 |

| Overbite (mm) | 30 | 9 | 21 | −3.93 | 1.69 | −1.40 | −7.10 |

| Control group | |||||||

| SN.GoGn (°) | 30 | 5 | 25 | 34.57 | 5.01 | 26.40 | 48.80 |

| ANB (°) | 30 | 5 | 25 | 4.99 | 2.74 | 1.20 | 10.40 |

| Overbite (mm) | 30 | 5 | 25 | −3.93 | 2.46 | −1.00 | −12.20 |

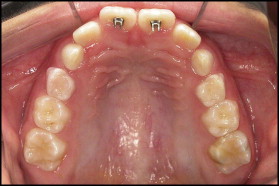

The protocol used in the treated group was Nogueira lingual bonded spurs associated with high-pull chincup therapy for 12 months. These appliances were bonded on the palatal and lingual surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular central incisors by using Concise Orthodontic Chemical Curing Adhesive (3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif). The bonded spurs were sharpened with a carborundum disk before installation, according to the prescription of Haryett et al and Justus. The bonded spurs were positioned in the cervical and incisal portions of the maxillary and mandibular incisors, respectively, to prevent possible future occlusal interferences ( Figs 1 and 2 ).

A high-pull chincup delivering 450 to 550 g of force per side was used. All patients were instructed to wear the chincup 14 to 16 hours a day for 12 months. To improve patient compliance with treatment, booklets were given to the parents, and they were instructed to record the number of hours of appliance usage every day.

Cephalometric data were obtained from lateral cephalograms taken at pretreatment and after 12 months of treatment with bonded spurs associated with high-pull chincup therapy for the treated group and at a comparable time period for the control group.

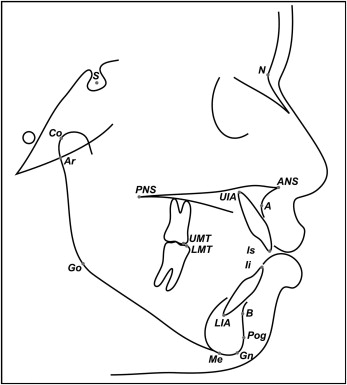

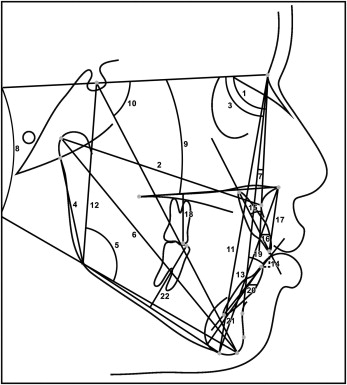

Cephalometric tracings and landmark identifications were made on acetate paper by 1 investigator (M.A.C.) for each group and then digitized with an AccuGrid XNT (model A30TLF digitizer; Numonics, Montgomeryville, Pa) for both groups ( Figs 3 and 4 ). These data were stored on a computer and analyzed with Dentofacial Planner software (version 7.02; Dentofacial Planner, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) that corrected the image magnification factors of the groups, which was 9.5%.

For the error study, 40 cephalograms from the 2 groups were randomly selected and remeasured by the same investigator (M.A.C.) after 1 month, following the guidelines suggested by Baumrind et al. Random errors were calculated with Dahlberg’s formula, and systematic errors were evaluated with dependent t tests. The random errors for linear measurements ranged from 0.33 mm for overbite to 0.81 mm for Ar-Go, and from 0.48° for NS.Gn to 1.62° for U1.NA for angular measurements. The systematic errors were significant for only 3 variables: lower anterior face height, L1-GoMe, and L6-GoMe ( Fig 4 ).

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare the proportions of the sexes between the treated and control groups.

Data distribution was analyzed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The pretreatment cephalometric characteristics and the treatment changes were normally distributed in the groups and therefore were compared with t tests. The results were regarded as significant at P <0.05. The analyses were performed with Statistica software (Statistica for Windows version 6.0; Statsoft, Tulsa, Okla).

Results

There was no significant intergroup difference for the initial and final ages ( Table I ).

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for sex distributions.

No significant differences were found between the initial characteristics of the treated and control groups, with the exception of Co-A, which was smaller for the control group (75.84 ± 2.91 mm) compared with the treated group (77.38 ± 2.9 mm).

Descriptive statistics regarding the mandibular plane angle, ANB, and the amount of initial overbite of the groups are described in Table II .

During treatment, there were a significantly greater decrease of the gonial angle, an increase in overbite, palatal tipping of the maxillary incisors, and vertical dentoalveolar development of the maxillary and mandibular incisors in the treated group ( Table III ).

| Variable | Treated group | Control group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Maxillary component | |||||

| SNA (°) | −0.33 | 1.60 | 0.18 | 1.98 | 0.27 |

| Co-A (mm) | 1.53 | 1.53 | 1.49 | 1.74 | 0.94 |

| Mandibular component | |||||

| SNB (°) | −0.0 | 1.29 | 0.33 | 1.73 | 0.40 |

| Ar-Go (mm) | −0.28 | 1.45 | 0.25 | 1.95 | 0.23 |

| Ar.GoMe (°) | −1.23 | 2.13 | 0.22 | 1.62 | <0.01 ∗ |

| Co-Gn (mm) | 1.64 | 1.40 | 2.14 | 1.49 | 0.19 |

| Maxillomandibular component | |||||

| ANB (°) | −0.33 | 1.21 | −0.16 | 1.62 | 0.65 |

| Vertical component | |||||

| SN.GoGn (°) | 0.01 | 1.76 | −0.29 | 2.06 | 0.55 |

| SN.PP (°) | 0.21 | 1.26 | −0.22 | 2.16 | 0.35 |

| NS.Gn (°) | 0.23 | 1.35 | −0.45 | 1.81 | 0.10 |

| AFH (mm) | 1.67 | 1.40 | 1.64 | 2.01 | 0.93 |

| PFH (mm) | 0.68 | 1.23 | 0.78 | 1.46 | 0.77 |

| LAFH (mm) | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.89 | 1.45 | 0.64 |

| Overbite (mm) | 5.23 | 1.69 | 1.98 | 1.41 | <0.0001 ∗ |

| Maxillary dentoalveolar component | |||||

| U1.NA (°) | −3.86 | 5.29 | 0.00 | 4.65 | <0.01 ∗ |

| U1-NA (mm) | 0.29 | 1.34 | 0.55 | 1.89 | 0.53 |

| U1-PP (mm) | 3.16 | 1.13 | 1.39 | 0.85 | <0.0001 ∗ |

| U6-PP (mm) | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 0.38 |

| Mandibular dentoalveolar component | |||||

| L1.NB (°) | −1.29 | 3.81 | 0.28 | 3.04 | 0.08 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 0.70 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.90 | 0.40 |

| L1-GoMe (mm) | 3.30 | 0.75 | 1.43 | 0.72 | <0.0001 ∗ |

| L6-GoMe (mm) | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.19 |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses