Introduction

Our objectives were to evaluate the evidence with regard to the effectiveness and stability of orthodontic treatment interventions for Class II Division 2 malocclusion in children and adolescents. This is a systematic review conducted according to the PRISMA statement.

Methods

The Cochrane Oral Health Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, and EMBASE were searched to November 2011. Relevant conference abstracts were also screened. No language restrictions were applied. Inclusion criteria were clinical studies with at least 20 subjects with Class II Division 2 malocclusion in which comparisons were made with an untreated Class II Division 2 malocclusion group, another treated Class II Division 2 malocclusion group, or neither. For included studies ranked best on the hierarchy of evidence, assessments of methodologic quality and risk of bias were undertaken. Abstracts and, when appropriate, full articles were examined independently by 2 investigators. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Treatment changes and stability with or without retainers were measured with the following: skeletal, soft tissue, dental, and occlusal changes; gingival health; temporomandibular joint status and related muscular activity; and quality of life.

Results

Of the 322 studies identified in the search, 20 met the final inclusion criteria. All had a high risk of bias.

Conclusions

Highly biased evidence exists with regard to management and stability of Class II Division 2 malocclusion. Guidelines are proposed based on current evidence.

Class II Division 2 malocclusion, characterized by retroclination of the maxillary incisors and a deep overbite, has a reported prevalence in children in the United Kingdom of 10%. Prevalences of 5% to 12% in other European populations and 3% to 4% in the United States have been reported, with the severe manifestation of “cover-bite” estimated at almost 2%. Although controversy surrounds the accompanying dentofacial characteristics, vertical skeletal factors make a greater contribution in more severe forms. The high lower lip line with associated resting pressure (approximately 2.5 times greater than upper lip resting pressure) has been shown to be linked with retroclination of the maxillary incisors. A strong genetic input exists with regard to the underlying skeletal pattern and dental anomalies, especially the increased prevalence of impacted maxillary canines.

Orthodontic treatment of Class II Division 2 malocclusion is recognized as difficult to treat and prone to relapse. A randomized clinical trial provides the highest-quality evidence with regard to the effectiveness of treatment interventions, and data from several trials have enabled meta-analysis to be undertaken on the effectiveness of growth modification for patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusion. Retrospective controlled studies have some benefit until results from prospective studies become available ; information from these studies has been included in orthodontic systematic reviews on Class III treatment and lingual arch-space maintenance. Although randomized and controlled clinical trials have been considered in a previous review, until now it would appear that no review has addressed all prospective and retrospective evidence regarding the effectiveness of orthodontic treatment and its stability for those with Class II Division 2 malocclusion.

The aims of this review were to evaluate the evidence with regard to the effectiveness and stability of orthodontic treatment interventions for Class II Division 2 malocclusion in children and adolescents and, if possible, to identify the most effective treatment strategies with a meta-analysis. The null hypothesis tested was that there is no difference in the effectiveness of any treatment interventions or their ability to promote stability for Class II Division 2 malocclusions. The reporting of this review is according to the PRISMA statement.

Material and methods

The criteria for selecting studies for the review were as follows. Randomized and controlled clinical trials were included because these were likely to contain evidence of acceptable quality. Prospective and retrospective studies with more than 20 subjects per intervention group were assessed also. A minimum sample of 20 was chosen based on the data from Stellzig et al, who found that patients with Class II Division 2 malocclusion treated with headgear and maxillary second molar extractions had a reduced interincisal angle of 12.6° (SD, 10.2°) compared with a historic, untreated control group. Using these data, we determined that a sample of 30 (ie, 15 subjects in each group) would be sufficient to detect a significant difference between treated and untreated groups with power of 90% and P <0.05; to account for the relatively wide standard deviations in incisor inclinations that are especially relevant to Class II Division 2 malocclusion outcome assessment, as well as to allow for dropouts and withdrawals, a minimum sample size of 20 per group was chosen. Smaller samples can have limited use, particularly if cephalometric data are being evaluated. Studies in which comparisons were made with either an untreated Class II Division 2 malocclusion group, another treated Class II Division 2 malocclusion group, or neither were included. Without a control group, limited conclusions regarding outcomes of treatment can be made because of the increased susceptibility to bias. Case reports were not considered for analysis because of their poor quality of evidence.

Children and adolescents who had treatment for Class II Division 2 malocclusion were included. Adults (mean age before treatment, >18 years) were excluded because of their lack of growth affecting the treatment outcome. For studies with mixed child or adolescent and adult samples, only data from the children and adolescents were considered.

Patients treated with 1-arch or 2-arch full fixed appliances (with or without extractions) were accepted, including those in which Class II elastics were used without adjunctive appliances. In addition, removable, functional, and headgear appliances, in isolation or combined with fixed appliances, were included. Patients treated by a combined orthodontic-orthognathic approach were excluded, since the focus was on orthodontic treatment only and the resultant stability. The type of appliance investigated was recorded to put studies into homogeneous groups, where meta-analysis was feasible.

Studies were included if they reported data on treatment or stability of treatment with regard to at least 1 of the following measures: skeletal, soft tissue, dental, and occlusal changes (preferably assessed with an occlusal index); gingival health; temporomandibular joint status or related muscular activity; or quality of life. If stability was assessed, patients were followed for a minimum of 12 months posttreatment, with or without retainers.

Several sources were used because a search confined to Medline only is generally deemed to be inadequate. The Cochrane Oral Health Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, and EMBASE were searched to November 2011. Journals that were hand-searched for the trials register are given on the Cochrane Oral Health Group website ( http://ohg.cochrane.org ). To identify records, usually 3 basic sets of terms were used: those that identify records related to the health condition of interest (Class II Division 2 malocclusion), those used to identify records related to the intervention being evaluated, and those that identify the type of study design to be included. Since a pilot run of the search strategy incorporating type of study design yielded no articles from any database, the search was confined to only 2 basic sets of search terms.

Details of the search strategies developed for all databases are given in Table I .

| Database | Search history | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OHG register | 1 | ((Malocclusion* OR bite* OR Angle* OR class) AND (“division 2” OR “div* 2” OR “div* II” OR “div* II”)) | 2 |

| CENTRAL | 1 | MALOCCLUSION, ANGLE CLASS II (Single term) | 1 |

| 2 | (“class II” AND (angle* OR malocclusion* OR bite*)) | ||

| 3 | 1 AND 2 | ||

| 4 | “div* 2” OR “div* II” | ||

| 5 | 3 AND 4 | ||

| MEDLINE | 1 | Malocclusion, Angle Class II/ | 264 |

| 2 | (“Class II” and (angle$ or malocclusion$ or bite$)).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] | ||

| 3 | or/1-2 | ||

| 4 | (“div$ 2” or “div$ II”).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] | ||

| 5 | 3 AND 4 | ||

| EMBASE | 1 | exp Malocclusion/ | 30 |

| 2 | malocclusion* OR bite* | ||

| 3 | 1 AND 2 | ||

| 4 | ((angle* OR (‘class 2’ OR ‘class ii’)) AND (‘division 2’ OR ‘division ii’)) | ||

| 5 | 3 AND 4 |

Conference proceedings and abstracts from the British Orthodontic Conference, European Orthodontic Conference, and International Association for Dental Research Conference were searched up to November 2011.

The references quoted in the studies identified were screened for any further trials, and international researchers potentially involved in Class II Division 2 malocclusion clinical trials were contacted to identify unpublished or ongoing randomized and controlled clinical trials. No language restrictions were applied.

The selection of articles, decisions about eligibility, study classifications, and data extractions were undertaken independently and in duplicate by 2 assessors (D.M., P.B.) without blinding to the authors, appliance types, or results obtained. All disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The following information was recorded for each eligible study on a customized data collection form: initials of reviewer, authors, year of publication, setting of the study, ages and sexes of the subjects, study design, defining criteria for the malocclusion, sample size calculation, treatment type and duration, dropouts, type of retention, outcome measures, methods of assessment, error study, and study results.

The primary outcome measures in the identified studies were skeletal, soft-tissue, dental, occlusal, or gingival changes with treatment or during an observation period. The secondary outcome measures were temporomandibular joint status or related muscular activity and quality of life.

For the eligible studies ranked highest on the hierarchy of evidence, quality was assessed according to the following criteria : sample size, sample based on power calculation, eligibility criteria described, random allocation, allocation concealment, baseline equivalence of groups, blinding of participants and caregivers (when possible), blinding of outcome assessors, point estimates and variability reported for primary outcome measures, appropriateness of statistical analysis, extent of dropouts and exclusions (trials with an intention-to-treat analysis were noted), and selective reporting.

For the eligible studies, a description of the quality items was tabulated, together with a judgment of low, high, or uncertain risk of bias. The criteria for risk of bias judgments for allocation concealment were according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.0.2).

All eligible studies were assessed for the appropriateness of their analyses.

It was planned that, if a sufficient number trials were identified, a funnel plot would be drawn, and a formal investigation of the degree of funnel plot asymmetry would be undertaken by using the method proposed by Egger et al. Asymmetry can represent a true trial and effect size relationship but might also indicate publication bias and other biases related to sample size.

The characteristics of the eligible studies were used to evaluate their clinical heterogeneity. After data extraction, it was intended to use the Cochrane test for heterogeneity before any meta-analysis, to produce forest plots demonstrating the overall effects of the treatment interventions.

Results

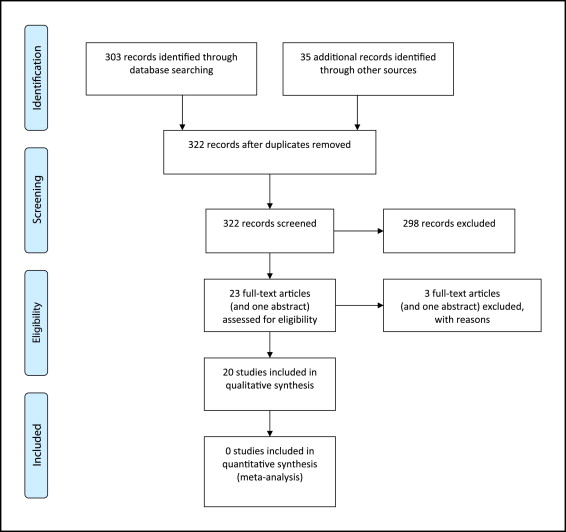

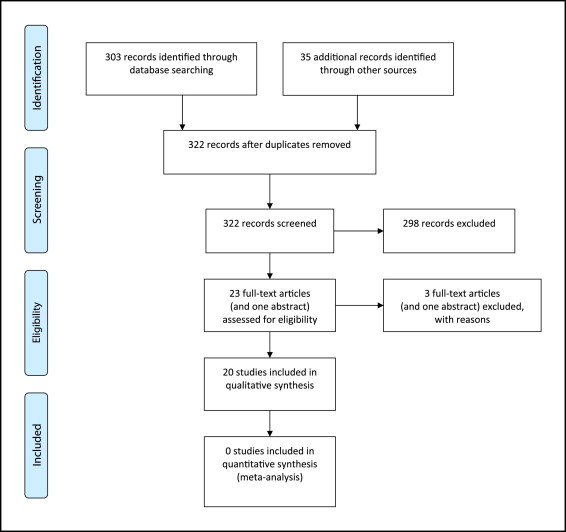

As described in the PRISMA statement, the review details are given in the Figure .

Of the 322 records resulting from the search strategies, only 23 full-text articles (and 1 abstract) were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Of these, 3 (plus the abstract) were subsequently excluded ( Table II ). Twelve studies (4 prospective, 8 retrospective) dealt with treatment ( Appendix I , Appendix II , 169.e1-169.e5 online), and 8 studies (all retrospective) dealt with stability ( Appendix III , 169.e6-169.e9 online). The study types, with numbers per group, were as follows: prospective cohort of treatment (2), prospective case series of treatment (2), retrospective cohort of treatment (4), retrospective case series of treatment (4), retrospective case-control of stability (1), retrospective cohort of stability (1), and retrospective case series of stability (6).

| Author/year | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| RCS, Cleall and BeGole (1982) | Uncertain whether subjects were ≤18 years of age |

| RCoS, Erickson and Hunter (1985) | Only 15 Class II Division 2 control subjects vs 34 (groups of 6, 14, 14) Class II Division treated subjects |

| RCS, Pancherz and von Bremen (abstract) (2000) | One of the 2 treated Class II Division 2 groups had only 14 subjects vs 23 in other treated group; PAR assessment |

| RCSTS, Kinzel et al (2002) | Adult treatment; 25 patients but only 11 at follow-up |

Key methodologic data are summarized in these tables ( Tables III and IV ). For study designs ranked best on the hierarchy of evidence, a risk of bias assessment was undertaken. Both assessors, however, deemed those studies to have a high risk of bias ( Tables III and IV ). All other designs were deemed to have inherent high risks of bias.

| Quality assessment factors | Moss, 1975 | Demisch et al, 1992 | Thuer et al, 1992 | Parker, 1995 | Kim and Little, 1999 | Stellzig et al, 1999 | Honn et al, 2006 | Tadic and Woods, 2007 | Woods, 2008 | Bock and Ruf, 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size reported | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size based on power calculation | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Eligibility criteria described | No | Yes | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Random allocation to groups | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Treatment allocation concealed | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Baseline equipoise between groups | Unclear | N/R | N/R | No | Age not sex | No | No | No | Yes | N/A |

| Blinding of treating clinician to treatment allocation | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Blinding of patients to treatment allocation | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Outcome assessors blinded to treatment allocation | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Point estimates and measure of variability presented for primary outcome measures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Appropriate statistical methods used to compare groups | Unclear | N/A | N/A | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Intention to treat analysis used | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Selective reporting | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Trial | Adequate sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Blinding of outcome assessors | Free of selective reporting | Free of other bias | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moss, 1975 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | High |

| Demisch et al, 1992 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | High |

| Thuer et al, 1992 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | High |

| Parker et al, 1995 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | High |

| Kim and Little, 1999 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | High |

| Stellzig et al, 1999 | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | High |

| Honn et al, 2006 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | High |

| Tadic and Woods, 2007 | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | High |

| Woods, 2008 | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | High |

| Bock and Ruf, 2008 | No | No | No | No | For skeletal maturity | No | No | High |

Prospective cohort studies of treatment for II/2M ( Appendix I )

One study followed Class II Division 2 malocclusion patients treated with functional appliance therapy, preceded in some patients by a removable appliance to procline the maxillary incisors. A distal path of closure was found in 50% of the Class II Division 2 malocclusion sample before treatment, and electromyographic assessment showed that masseter and temporalis muscle activity became more “normal” during functional appliance treatment. Additionally, a low gonial angle was associated with increased masseteric activity.

Another study made comparisons with a contemporaneous untreated Class II Division 2 malocclusion control group. The comparisons were based on age and 1 of 3 mandibular growth directions; however, it was not clear whether the matching of the treatment and control groups was done prospectively or retrospectively. Sex was closely, but not exactly, matched between the treated and control groups. Nonextraction treatment, started in the late mixed dentition for overbite reduction in Class II Division 2 malocclusion subjects with mesofacial or brachyfacial growth patterns (normal or reduced lower facial height, respectively), led to a mean forward movement of B-point of 4 to 5 mm compared with the controls during the treatment period (mean durations, 2.4 and 2.2 years, respectively).

Prospective case series of treatment for II/2M ( Appendix I )

Two studies on the same cohort reported the results of maxillary removable appliance therapy to procline the maxillary incisors and reduce the overbite, followed by functional appliance therapy ( Appendix I ). When the anteroposterior distance for the retruded to the intercuspal mandibular position was compared from the start of treatment with after the incisor proclination, no statistically significant difference was found. The muscle activity was also unchanged after treatment; this contrasts with the study of Moss. The findings led the authors to the opinion that the mandible does not move anteriorly during treatment of Class II Division 2 malocclusion.

Retrospective cohort studies of treatment for II/2M ( Appendix II )

Selection criteria for subjects with Class II Division 2 malocclusion varied between studies, so interstudy comparisons were not appropriate. Extraction and nonextraction treatments were assessed ( Appendix II ). The only study to use an untreated Class II Division 2 malocclusion control group compared extraction of 4 first premolars vs maxillary second permanent molars. The control group was derived from the Belfast Growth Study, but it was not clear whether there was sex matching with the treated groups. Furthermore, the treated and control groups were not equivalent at baseline, although almost were approximately similar on completion of treatment. The amount of crowding in either group was not specified. In addition, there was variation with regard to intrusion mechanics for overbite reduction, as well as the use of headgear as an adjunct to fixed appliances in many patients in both extraction groups. Four premolar extractions, rather than maxillary second permanent molar extractions, produced more retraction of the upper lip and less reduction of the interincisal angle; premolar extraction spaces also reopened at the end of treatment in more than 40% of the patients.

With maxillary premolar extractions only, there were wide variations in nasolabial angle changes; although there was a mean increase of about 2.5° for subjects with Class II Division 2 malocclusion, this was not significantly different from the Class II Division 1 malocclusion group. Overbite was successfully reduced by several treatment approaches; the mean decreases varied from 1.9 mm to almost 5 mm, and the mean decrease in the interincisal angle varied from 6° to almost 22°, respectively.

Retrospective case series of treatment for II/2M ( Appendix II )

Selection criteria for Class II Division 2 malocclusion varied between studies ( Appendix II ). Three studies assessed functional appliance treatment : one with a Herbst and the others with a removable functional appliance. Nonextraction treatment was specified in 2 studies, and 2 studies did not mention whether there were extractions. Maxillary apical base size was the strongest predictor of occlusal change.

Retrospective case-control study of stability for II/2M ( Appendix III )

At a mean time of 15.2 years out of retention, the mean amounts of relapse in overbite and interincisal angle correction were 40% and 59%, respectively ( Appendix III ). The overbite relapse mirrored that of the reduction in lower anterior facial height (almost 40%). As the incisor segments uprighted, incisor crowding increased especially in the mandibular arch, but this varied between subjects. Mandibular arch extractions did not appear to increase the posttreatment overbite if appropriate treatment mechanics were used; rather, the initial overbite was the best predictor of posttreatment overbite, but predictability was not high (R 2 = 0.42). The chance of maintaining an overbite less than 4 mm in the long term was deemed to be less than 50%. Posttreatment vertical facial growth contributed to the maintenance of overbite correction. Molar relationship correction was stable.

Retrospective cohort study of stability for II/2M ( Appendix III )

After 2-phase (Herbst and fixed appliances) nonextraction treatment and an average of 27 months of retention, overbite correction was more stable in late (about 86%) than in early (70%) adolescents. Molar relationships relapsed minimally (5%-7%).

Retrospective case series of stability for II/2M ( Appendix III )

The retention type, duration of retention, and treatment approach varied, but, where stated, a nonextraction approach was favored. Although at 2 to 3 years postretention, successful proclination of maxillary (about 5°-10°) and mandibular (about 4°-10°) incisors has been reported, the standard deviations were large, and relapse occurred in both arches usually associated with the return of incisor crowding. Overbite increased after treatment with an associated increase in interincisal angle and a relapse in maxillary incisor inclination correction ; the latter was found to be independent of retainer type, and there were large interindividual variations. Incisor crowding increased simultaneously with overbite relapse and was more marked in the mandibular arch, supporting the findings of Kim and Little. Mandibular incisor proclination and expansion of the intercanine width relapsed. The former was found to be more stable than maxillary incisor proclination, although both incisor segments uprighted. The greater the treatment change in maxillary incisor inclination, the greater the relapse. In a sample with a mix of removable and fixed appliance treatments (some combined), a mean value of about 19% relapse in overbite was found at 2 years post-treatment. In other postretention studies, the mean overbite relapse varied from about 20% to about 30% (0.8-1.2 mm) when assessed at 2 and 5 years, respectively, to about 27% at a mean period of 7 years (0.96 mm). Time after retention was correlated with the extent of overbite relapse and mandibular incisor irregularity. No variables were found to determine the prognosis for overbite stability, with an anterior growth rotation of the mandible evident after treatment, especially in male subjects. Overcorrection of overbite did not show a net improvement at a mean time of 7 years out of retention.

The level of the lower lip after treatment had a significant influence on the relapse tendency of the corrected incisor relationships. Although it is recommended to reduce lower lip coverage to a maximum of 3 mm, a mean decrease of 0.6 mm, although statistically significant, was not judged to be clinically significant. At a minimum of 3 years postretention, 10% of maxillary arches and 30% of mandibular arches had unacceptable irregularity. Molar relationships were stable after correction ; this confirmed the findings of others.

Due to the heterogeneity of all included studies, it was not possible to undertake a meta-analysis to determine the most effective means of treatment or the stability for this malocclusion. There is insufficient high quality evidence to reject the null hypothesis tested in this review.

Results

As described in the PRISMA statement, the review details are given in the Figure .

Of the 322 records resulting from the search strategies, only 23 full-text articles (and 1 abstract) were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Of these, 3 (plus the abstract) were subsequently excluded ( Table II ). Twelve studies (4 prospective, 8 retrospective) dealt with treatment ( Appendix I , Appendix II , 169.e1-169.e5 online), and 8 studies (all retrospective) dealt with stability ( Appendix III , 169.e6-169.e9 online). The study types, with numbers per group, were as follows: prospective cohort of treatment (2), prospective case series of treatment (2), retrospective cohort of treatment (4), retrospective case series of treatment (4), retrospective case-control of stability (1), retrospective cohort of stability (1), and retrospective case series of stability (6).

| Author/year | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| RCS, Cleall and BeGole (1982) | Uncertain whether subjects were ≤18 years of age |

| RCoS, Erickson and Hunter (1985) | Only 15 Class II Division 2 control subjects vs 34 (groups of 6, 14, 14) Class II Division treated subjects |

| RCS, Pancherz and von Bremen (abstract) (2000) | One of the 2 treated Class II Division 2 groups had only 14 subjects vs 23 in other treated group; PAR assessment |

| RCSTS, Kinzel et al (2002) | Adult treatment; 25 patients but only 11 at follow-up |

Key methodologic data are summarized in these tables ( Tables III and IV ). For study designs ranked best on the hierarchy of evidence, a risk of bias assessment was undertaken. Both assessors, however, deemed those studies to have a high risk of bias ( Tables III and IV ). All other designs were deemed to have inherent high risks of bias.

| Quality assessment factors | Moss, 1975 | Demisch et al, 1992 | Thuer et al, 1992 | Parker, 1995 | Kim and Little, 1999 | Stellzig et al, 1999 | Honn et al, 2006 | Tadic and Woods, 2007 | Woods, 2008 | Bock and Ruf, 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size reported | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size based on power calculation | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Eligibility criteria described | No | Yes | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Random allocation to groups | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Treatment allocation concealed | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Baseline equipoise between groups | Unclear | N/R | N/R | No | Age not sex | No | No | No | Yes | N/A |

| Blinding of treating clinician to treatment allocation | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Blinding of patients to treatment allocation | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Outcome assessors blinded to treatment allocation | No | No | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Point estimates and measure of variability presented for primary outcome measures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Appropriate statistical methods used to compare groups | Unclear | N/A | N/A | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Intention to treat analysis used | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | No | No | Unclear | No |

| Selective reporting | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses