Introduction

Long-term changes in the dentitions of orthodontic patients have been studied. However, most studies in the literature report findings after only a few years posttreatment. In this study, we examined records an average of 24 years after active treatment. The purpose was to answer 2 questions: (1) does irregularity increase with time after treatment, and (2) how much relapse can be expected if a conservatively treated sample is recalled 2.5 decades after active treatment?

Methods

The sample consisted of dental casts of 52 women who were treated in the mid-1970s to the early 1980s with 0.022 × 0.028-in standard edgewise appliances. Each was given a maxillary Hawley retainer and either a mandibular Hawley or a banded canine-to-canine retainer at debanding. Retention lasted 24 to 32 months. The same practitioner treated all the patients. The sample is one of convenience; specifically, inclusion depended only on each patient’s willingness to return for a recall examination. Records were collected at 3 examinations for each patient: start of treatment, end of the active phase of treatment, and long-term retention recall. The long-term maxillary and mandibular casts were measured and occluded in maximum intercuspation. Variables were measured, including incisor overjet and overbite, buccal segment relationship of the first molars and canines, and incisor irregularity in each arch. Variables were measured on the casts with digital readout sliding calipers precise to 0.001 mm.

Results

Mandibular incisor irregularity at recall was less than 3.5 mm in 77% of the patients examined. Correction of the maxillary incisor irregularity remained relatively stable over the time interval studied. Buccal segment Class II correction remained stable at the recall examination.

Conclusions

Orthodontic treatment can yield reasonably good long-term stability in both occlusal correction and tooth alignment.

Instability of tooth alignment and occlusal relationships occurs to some extent in practically every patient. Relapse is defined as the tendency of teeth to return toward their pretreatment positions. It is a complex problem that appears to be multifaceted. Factors that can be linked to relapse include unfavorable skeletal growth patterns, improper treatment plans, uncooperative patients, muscular functions and habits, changes in arch forms, occlusion, and transseptal fibers.

In this study, we explored the stability of orthodontic tooth alignment and Class II dentition occlusal correction. Dental casts (52 subjects) were made at the start of treatment (T1), after the active phase of treatment (T2), and at an average of 24 years after treatment (T3). All subjects whose records were in the study were treated by 1 clinician (J.L.V.). The purpose of the study was to use dental casts to evaluate the long-term changes (>20 years) in the dental arches. Changes in the dentition over this interval of about 2.5 decades include any dental relapse that occurred along with aging changes that impacted the dentition.

Most orthodontic patients are treated in their adolescence. This fact alone leaves ample opportunity for subsequent growth of the maxillary and mandibular complexes to effect movement of the teeth into different positions. If a patient continues to grow after treatment, there might be lingually directed pressure on the mandibular incisors with the forward displacement of the mandible. Perera reported a relationship between mandibular growth and mandibular anterior crowding in untreated subjects (n = 29). Perera indicated that forward rotational growth in the mandible is closely related to mandibular incisor crowding that commonly occurs after the adolescent years. However, Shields et al determined that horizontal and vertical growth showed no statistical association with posttreatment mandibular anterior irregularity.

Although orthodontic patients tend to exhibit decreases in tooth alignment in the long term, arch length decreases and incisor crowding increases in the dental arches of patients who have had no orthodontic treatment. Untreated patients have a decrease in arch length with no change to the arch width in the permanent dentition.

Lundström evaluated untreated subjects for changes in the dimensions of the dental arches in the early permanent dentition and again 14 years later. The early permanent dentition sample included 100 subjects, most of whom were between 12 and 15 years old. Forty-one subjects returned for an examination 14 years later. Arch width was measured at the first premolar and the first molar, and arch length was measured as the distance between the line joining the first molars and the incisal edge of the central incisors. Arch crowding was simply given a value from +2 for spacing to − 4 for severe crowding. Lundström found that arch length was reduced by an average of 1 to 2 mm, whereas the mean arch width did not change. These changes in the dental arch were accompanied by increased crowding.

Richardson and Gormley evaluated 20 untreated men and 26 untreated women for changes in mandibular arch dimensions and crowding in the adult dentition. The sample represented a variety of malocclusions as well as normal and near normal occlusions. Study casts were collected at ages 18 (T1), 21 (T2), and 28 (T3) years. Incisor crowding, intercanine width, intermolar width, and arch length were measured on the mandibular casts at all 3 time points. A statistically significant mean increase in crowding (0.1 mm) was observed from T1 to T2. Arch length also decreased significantly by 0.2 mm. No change was found for arch widths from T1 to T2. Changes from T2 to T3 were similar to the changes from T1 to T2 but to a greater extent. Crowding increased significantly (0.2 mm) with a significant change from T2 to T3 for the grouped sample. Molar width increased significantly in the men (0.2 mm), but not in the women (0.0 mm).

Sinclair and Little reported on an untreated sample of 65 subjects with normal occlusions. Changes in the dental arch from the mixed dentition to the early permanent dentition and into early adulthood were studied. A normal occlusion was defined as a dental and skeletal Angle Class I relationship. The irregularity index, mandibular arch length, mandibular intercanine width, overbite, and overjet were measured. Measurements were made at 3 time points: T0, mixed dentition; T1, early permanent dentition, and T2, adult (18 years of age) dentition. In a few cases, near perfect alignment progressed to mild or moderate crowding by early adulthood. Women tended toward greater arch constriction and incisor crowding than did the men. Overjet and overbite showed only minor overall changes.

Sinclair and Little, in another study of untreated subjects, found that arch length decreased from the mixed dentition into early adulthood, whereas incisor irregularity increased from 13 to 20 years of age. Changes in mandibular arch length, mandibular intercanine width, overbite, and overjet were not associated with mandibular crowding at 13 years of age as measured by the change in incisor irregularity. They concluded that, because no clinically significant variables were predictive of mandibular incisor crowding, the changes were due to normal maturational processes.

De La Cruz et al evaluated records of 45 patients with Class I occlusions and 42 patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusions, all of whom were treated with first premolar extractions. Dental casts were collected at the start of treatment (age, 13.0 years), posttreatment (age, 15.7 years), and a minimum of 10 years posttreatment (age, 33.7 years). They found that the changes in eccentricity, intercanine width, intermolar width, arch length, and irregularity index from the end of treatment to the recall examination were all statistically significant ( P <0.05). At the recall examination, intercanine width, intermolar width, and arch length had all decreased, but irregularity index had increased.

Material and methods

This long-term analysis of tooth alignment and occlusal stability was based on the study of 52 American women who were recalled an average of 24.7 years after their active phase of orthodontic treatment. All patients were treated with a 0.022 × 0.028-in slot size appliance with no tip or torque in the brackets. Canine retraction was accomplished with J hook headgear and elastic chains. The remaining space was closed with 0.020 × 0.025-in closing loop archwires. The archwires used for finishing were 0.020 × 0.025 or 0.0215 × 0.028 in. At deband, maxillary Hawley retainers and mandibular canine to canine or mandibular Hawley retainers were inserted. Retention lasted an average of 30 months.

All patients in the study were treated during adolescence by the same practitioner (J.L.V.). To collect the sample, the practitioner actively sought former patients who had been treated in the mid to late 1970s to the early 1980s. At the recall examination of those who agreed to participate, informed consent was obtained, and records including a lateral cephalogram, photographs, and study casts were taken. The final sample was composed of 52 women. Men and all patients treated without extractions were excluded from the study to enhance the homogeneity of the sample.

We report on data collected at the 3 examinations of each patient; T1, T2, and T3. The focus of the study was on the changes in tooth alignment and occlusal correction from T2 to T3. Extractions in the sample can be divided into 3 categories: 24 patients were treated with first premolar extractions, 11 patients were treated with maxillary first and mandibular second premolar extractions, and 14 patients were treated with maxillary and mandibular second premolar extractions. Most of the subjects (39) had a Class II malocclusion at T1 (Class I, 12 patients; Class III, 1 patient).

The maxillary and mandibular casts at T3 were measured and then occluded in maximum intercuspation. The following variables were measured: (1) incisor overjet, (2) incisor overbite, and (3) buccal segment relationship of the first molars and canines. Incisor irregularity in each arch was measured. These variables were measured on the casts with digital readout sliding calipers precise to 0.001 mm.

The patients were treated early in adolescence, shortly after all permanent teeth (except third molars) had emerged. Their mean age at T1 was 13.3 years. Comprehensive treatment of the sample lasted an average of 2.3 years. Their mean age at T3 was 39.4 years, or 24.7 years after the active phase of treatment.

Results

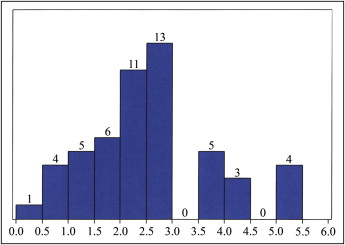

The alignment of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth of the patients in the study was quantified by using Little’s irregularity index. Mandibular incisor irregularity was significantly reduced by an average of 3.5 mm during treatment. One third of the improvement (35%) in mandibular incisor irregularity was lost from T2 to T3, but no patient had greater than 5.5 mm of mandibular incisor irregularity at T3. Mandibular incisor irregularity at T3 was less than 3.5 mm (the limit suggested by Little et al as clinically acceptable) in 77% of the patients ( Fig 1 ).

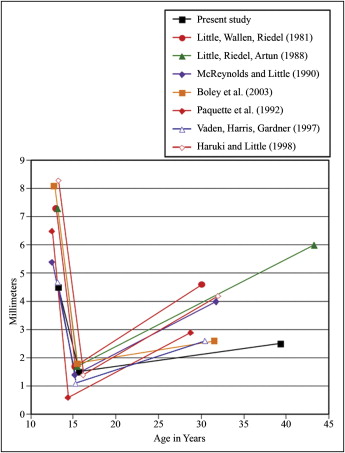

Maxillary incisor irregularity improved significantly ( P <0.0001) during treatment from an average of 6.8 mm at T1 to an average of 1.6 mm at T2. Maxillary incisor irregularity relapsed by almost 0.5 mm during the 24.7 years after treatment. This change achieved significance statistically ( P = 0.0412), but 0.5 mm is clinically insignificant, particularly if distributed across the 5 intertooth contacts. Figure 2 plots the changes in mandibular incisor irregularity. It also compares mandibular incisor irregularity in our study with that of comparable retention studies.

Mandibular intercanine width increased significantly ( P <0.0001), from an average of 30.3 to 32.5 mm, during treatment. Intercanine width subsequently decreased to a significant extent (1.2 mm) during the posttreatment to recall period ( P <0.0001). Maxillary intercanine width significantly increased by an average of 1.7 mm during treatment ( P <0.0001). This intercanine width then decreased by 0.7 mm during the posttreatment period. This decrease was significant ( P <0.0001).

Overjet decreased significantly during treatment, from 6 to 3 mm ( P <0.0001). Overjet increased significantly ( P <0.0001) from 3.0 to 3.5 mm during the recall period. Incisor overbite decreased significantly during treatment ( P <0.0001), from a mean of 4 mm to 2.5 mm. A statistically significant rebound, averaging 0.7 mm, occurred after treatment.

Interpremolar widths in both arches decreased significantly by 0.7 mm each ( P <0.0001) during the posttreatment interval. Intermolar widths in both arches significantly decreased ( P <0.0001) during treatment, by 1.3 and 2.2 mm, respectively, but changed little from T2 to T3.

The average buccal segment relationship of the sample at T1 was − 1.4 mm, meaning that the mesiobuccal cusp tip of the maxillary first molar was 1.4 mm mesial to the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar. The molar correction during treatment was highly significant ( P <0.0001). The buccal segment relationship averaged 0.2 mm at T2 (range, − 2.5 to 3.0 mm). The correction remained stable during the posttreatment period, with a − 0.2 mm average change that was not statistically significant.

Results

The alignment of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth of the patients in the study was quantified by using Little’s irregularity index. Mandibular incisor irregularity was significantly reduced by an average of 3.5 mm during treatment. One third of the improvement (35%) in mandibular incisor irregularity was lost from T2 to T3, but no patient had greater than 5.5 mm of mandibular incisor irregularity at T3. Mandibular incisor irregularity at T3 was less than 3.5 mm (the limit suggested by Little et al as clinically acceptable) in 77% of the patients ( Fig 1 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses