Surgical Anatomy of the Parotid Gland and Parapharyngeal Space

The Deep or Medial Lobe of the Parotid Gland

Local Ligaments from the Styloid Process

Surgical Anatomy of the Submandibular Gland

Surgical Anatomy of the Sublingual Gland

Surgical Anatomy of the Minor Salivary Glands

Indications and Patient Selection

Patient Information and Consent

General Aspects of Parotid Gland Surgery

Lateral or Superficial Parotidectomy

Partial Lateral or Superficial Parotidectomy

Surgery of Accessory Parotid Tissue

Operative Steps—Submandibular Gland

Operative Steps—Sublingual Gland

Operative Steps—Minor Salivary Glands

Tips and Tricks in Salivary Surgery

Introduction

Benign salivary gland neoplasms are relatively common and can manifest in both the major and minor salivary gland sites of the head and neck region. The parotid gland is the most frequent site, and pleomorphic adenoma is the most common histopathological type, representing 80% of all benign neoplasms, with an estimated incidence of 60 per million population per year in the United Kingdom. The diagnosis is usually established by clinical examination and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). Additional radiological imaging is sometimes required. The treatment of choice is complete surgical excision.

Benign salivary gland tumors are common, and they may grow over time and can create a cosmetically unattractive or unsightly mass on the face. As the tumor increases in size, it can affect swallowing and breathing, depending on its location. If left untreated, a small proportion undergo malignant transformation. Incomplete removal is associated with recurrent disease, with the resulting clinical findings and increasing difficulties with management (Chapter 24).

Surgical Anatomy of the Parotid Gland and Parapharyngeal Space

Precise knowledge of the anatomy of major and minor salivary glands is essential when performing exploratory and excision surgery.

Precise knowledge of the anatomy of major and minor salivary glands is essential when performing exploratory and excision surgery.

Parotid Location

Parotid Location

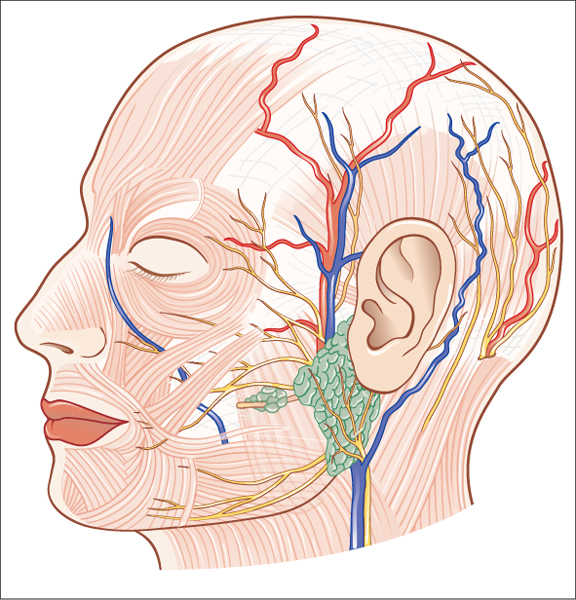

The parotid gland is located between the posterior border of the mandible and the mastoid process of the temporal bone (Fig. 22.1). The external auditory meatus, the temporomandibular joint, and the zygomatic process of the temporal bone all lie posterior and superior to the gland. The tail of the parotid is frequently located inferiorly in the neck, as low as the hyoid. On its deep (medial) surface lies the styloid process of the temporal bone, and it overlies the angle of the mandible and the transverse process of the atlas (C1) vertebra.

Fig. 22.1 The lateral head, illustrating the location of the parotid gland in the preauricular area and the local nerves (great auricular nerve and facial nerve, cranial nerve VII) and blood vessels.

Fibrous Capsule

Fibrous Capsule

The parotid gland is surrounded by a fibrous capsule. This passes up from the neck and was formerly thought to split to enclose the gland. The deep layer is attached to the mandible and the temporal bone at the tympanic plate and styloid and mastoid processes. This superficial layer is now considered to be part of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). Anteriorly, the superficial layer of the parotid capsule is thick and fibrous, but more posteriorly it becomes a thin, translucent membrane. Within this fascia are scant muscle fibers running parallel with those of the platysma. This superficial layer of the parotid capsule appears to be continuous with the fascia overlying the platysma muscle. Anteriorly, it forms a separate layer overlying the masseteric fascia, which is itself an extension of the deep cervical fascia. The peripheral branches of the facial nerve and the parotid duct lie within a loose cellular layer between these two sheets of fascia.

The Superficial Lobe

The Superficial Lobe

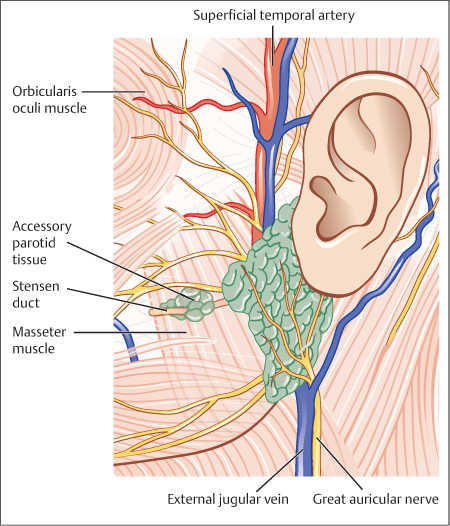

The superficial surface of the parotid gland is covered with skin and platysma muscle. Some terminal branches of the great auricular nerve lie superficial to the gland tissue. At the superior border of the parotid lie the superficial temporal vessels, with the artery anterior to the vein (Fig. 22.2). The auriculotemporal branch of the mandibular nerve runs just deep to the superficial temporal vessels.

The Deep or Medial Lobe of the Parotid Gland

The Deep or Medial Lobe of the Parotid Gland

The deep (medial) surface of the parotid gland lies on structures called the parotid bed. Anteriorly, the gland lies over the masseter muscle and the posterior border of the mandible from the angle up to the condyle. As the gland wraps around the ramus, it is related to the medial pterygoid muscle at its insertion onto the deep aspect of the angle. Posteriorly, the parotid is molded around the styloid process and the styloglossus, stylohyoid, and stylopharyngeus muscles from below upwards. Behind this, the parotid lies on the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The digastric and the styloid muscles separate the gland from the underlying internal jugular vein, the external and internal carotid arteries, the glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves, and the sympathetic chain.

Fig. 22.2 The parotid bed, illustrating the facial nerve trunk and the upper and lower divisions.

Local Ligaments from the Styloid Process

Local Ligaments from the Styloid Process

The fascia that covers the muscles in the parotid bed thickens to form two named ligaments. The stylomandibular ligament passes from the styloid process to the angle of the mandible. The mandibulostyloid ligament (the angular tract) passes between the angle of the mandible and the stylohyoid ligament. Inferiorly, it usually extends down to the hyoid bone. These ligaments are all that separates the parotid gland anteriorly from the posterior pole of the superficial lobe of the submandibular gland.

The Parotid Duct

The Parotid Duct

The parotid duct emerges from the anterior border of the parotid gland and passes horizontally across the masseter muscle. It can be found by drawing a line from the tragal cartilage of the pinna to bisect a line drawn from the alar base of the nose to the commissure of the lip. The middle third of this line is the surface marking of the parotid duct. Branches between the buccal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve cross the duct. At the anterior border of the masseter, the duct bends sharply to perforate the buccal fat pad and the buccinator muscle at the level of the upper second molar teeth. The duct then bends again to pass forward for a short distance before entering the oral cavity at the parotid papilla.

The Facial Nerve

The Facial Nerve

The facial nerve exits the skull base at the stylomastoid foramen of the temporal bone. The nerve lies about 9 mm superior to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and 11 mm from the bony external meatus. The facial nerve trunk then passes downwards and forward over the styloid process and the associated muscles for about 13 mm before entering the substance of the parotid gland. The first part of the facial nerve gives off the posterior auricular nerve supplying the auricular muscles and also branches to the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles.

The extratemporal facial nerve trunk (Table 22.1) can be identified proximally using an antegrade technique, most commonly taught,1 or with a retrograde technique.2 The two most reliable surgical landmarks used to identify the facial nerve trunk are the tympanomastoid suture line and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.3 If the main trunk is not identifiable or cannot be safely approached proximally at the stylomastoid foramen, alternative means of identifying the trunk must be used. One approach is to locate a branch of the facial nerve distally using a retrograde technique. The marginal mandibular branch usually passes superficial to the posterior facial vein, which has been encountered and divided when elevating the parotid off the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The buccal branch can be identified at the anterior border of the parotid gland, at a point horizontal from the nasal alar rim to the inferior rim of the external auditory canal. The zygomatic branches can be identified as the nerve crosses the zygomatic arch, usually at its midportion, between the outer canthus of the eye and the temporomandibular joint.4 If all of the above approaches fail, the transmastoid approach can be used, drilling down the mastoid to identify the facial nerve in the middle ear and following it inferiorly to reach the tympanomastoid suture.

|

1. The tympanomastoid (TM) suture line: the facial nerve trunk is usually located approximately 2–4 mm deep to the inferior end of the tympanomastoid suture line. This landmark may not be visualized and can only be detected on palpation |

|

2. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle: the facial nerve trunk is located 0.5–1.5 cm deep and above the muscle as it attaches the digastric groove |

|

3. The tragal pointer: the facial nerve trunk is located approximately 1–2 cm deep and slightly anteroinferiorly. The tragal pointer has a blunt and variable tip that can change with retraction. It is probably the least consistent landmark to use, as it does not point in the appropriate direction in some 80% of cases |

|

4. The styloid process: the facial nerve trunk is located in the inferior and superficial soft tissue. If the styloid process is used to identify the nerve, the surgeon is likely to become lost and there is a risk of injury to the nerve |

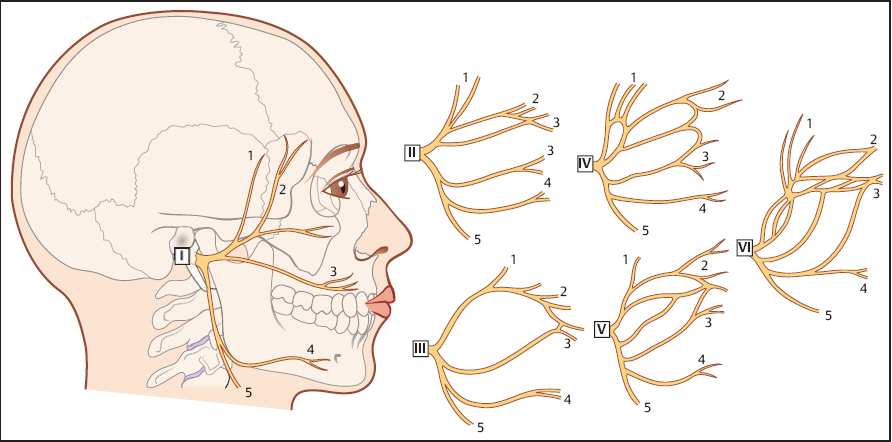

On entering the parotid gland, the facial nerve separates into two divisions—the temporofacial and cervicofacial trunks. The division of the nerve is known as the pes anserinus (“goose’s foot”). From these two divisions, the facial nerve further divides into five named branches—the temporal and zygomatic, usually from the upper division; and the buccal, mandibular, and cervical branches from the lower division, but the exact configuration is variable. The peripheral branches of the facial nerve form anastomoses between adjacent branches to form the parotid plexus. Davis et al.5 studied these patterns in 350 cadaveric facial nerves and described six patterns (Fig. 22.3). They demonstrated that in only 6% of cases was there any anastomosis between the mandibular branch and the adjacent branches. Miehlke et al.6 described eight branching patterns in which no anastomosis between the branches was seen in 48% of patients.

The Parapharyngeal Space

The Parapharyngeal Space

The parapharyngeal space (PPS) is a potential space located in the upper cervical region. The PPS is not readily accessible to routine clinical examination and remains silent until affected by pathological processes such as infections or tumors. The potentially wide range of benign and malignant neoplasms encountered in this complex and deep anatomic region contributes to the challenge of surgical treatment.

Boundaries

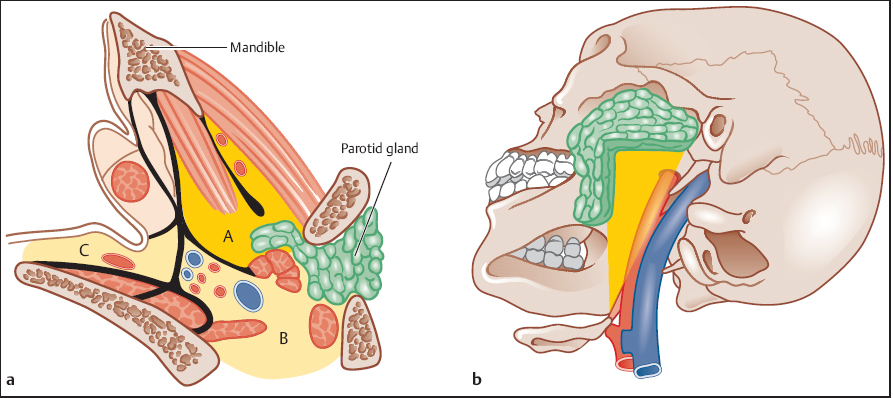

The PPS is described as an inverted five-sided pyramid, with its base at the skull base and the apex at the greater cornu of the hyoid bone (Fig. 22.4a).

The PPS is described as an inverted five-sided pyramid, with its base at the skull base and the apex at the greater cornu of the hyoid bone (Fig. 22.4a).

The superior boundary is a small area of the temporal and sphenoid bones that includes the carotid canal, the jugular foramen, and the hypoglossal foramen. The fascia covering the medial pterygoid muscle borders this region of the skull base laterally; medially lies the attachment of the pharyngobasilar fascia and posteriorly the prevertebral fascia. Anteriorly, the medial and lateral borders converge.

The superior boundary is a small area of the temporal and sphenoid bones that includes the carotid canal, the jugular foramen, and the hypoglossal foramen. The fascia covering the medial pterygoid muscle borders this region of the skull base laterally; medially lies the attachment of the pharyngobasilar fascia and posteriorly the prevertebral fascia. Anteriorly, the medial and lateral borders converge.

The inferior boundary is formed by the greater horn of the hyoid, the facial attachments of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the sheath of the submandibular gland.

The inferior boundary is formed by the greater horn of the hyoid, the facial attachments of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the sheath of the submandibular gland.

The posterior boundary is the prevertebral fascia.

The posterior boundary is the prevertebral fascia.

The medial boundary is formed by the pharyngobasilar fascia overlying the superior constrictor muscle. Further medially lies the tonsil.

The medial boundary is formed by the pharyngobasilar fascia overlying the superior constrictor muscle. Further medially lies the tonsil.

Fig. 22.3 The chief types of branching of the facial nerve, as described by Davis et al.5

Fig. 22.4 a, b The parapharyngeal space (PPS).

a The prestyloid (A) and post-styloid (B) compartments of the PPS

b The inverted pyramid of the prestyloid compartment, with the and their close proximity to the retropharyngeal space (C). base at the skull base (superiorly) and the apex at the greater cornu of the hyoid bone (inferiorly).

The lateral boundary in the upper part of the PPS, from anterior to posterior, is formed by the ramus of the mandible, the fascia of the medial pterygoid muscle, and the retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Below the mandible, the lateral boundary is formed by the fascia overlying the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

The lateral boundary in the upper part of the PPS, from anterior to posterior, is formed by the ramus of the mandible, the fascia of the medial pterygoid muscle, and the retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Below the mandible, the lateral boundary is formed by the fascia overlying the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

The anterior boundary is the pterygomandibular raphe, and below is the submandibular space.

The anterior boundary is the pterygomandibular raphe, and below is the submandibular space.

Spaces or Compartments

The prestyloid space, the anterior space of the PPS, contains fat and parotid salivary tissue, whereas the retrostyloid space posteriorly contains the carotid sheath and is continuous with the upper mediastinum (Fig. 22.4 b). These spaces are separated by the tensor veli palatini muscle and fascia that arises from the styloid process and crosses posteriorly into the parapharyngeal fat.

The Prestyloid Space

The prestyloid space extends superiorly into a blind pouch formed by the joining of the medial pterygoid fascia to the tensor veli palatini fascia. Most of the space is occupied by fat. It contains the inferior alveolar, lingual, and auriculotemporal nerves and maxillary artery—resulting in neoplasms that are limited to the salivary gland, lipomas, and rarely neurogenic tumors (Table 22.2).

|

Structure |

Prestyloid |

Post-styloid or retrostyloid |

|

Arteries |

Internal maxillary |

Internal carotid |

|

|

|

Ascending pharyngeal |

|

Veins |

|

Internal jugular |

|

Nerves |

Auriculotemporal |

Cranial nerves IX, X, XI, XII |

|

|

|

Cervical sympathetic chain |

|

Lymph nodes |

|

Present |

|

Glomus tissue |

|

Present |

|

Salivary tissue |

Parotid tissue |

|

The Retrostyloid or Post-Styloid Space

The retrostyloid or post-styloid space contains the internal carotid artery with the internal jugular vein postero-lateral to the artery at the skull base. Cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII and the sympathetic chain also occupy this space.

Deep Lobe of the Parotid

The deep lobe of the parotid gland is defined as the parotid tissue that lies medial to the plane of the facial nerve. Less than 20% by volume of parotid salivary tissue is located deep to the facial nerve, and tumors located here are therefore uncommon. Those located in proximity to the lateral lobe present either in the retromandibular area or as a parapharyngeal space mass.

Accessory Parotid Tissue

Accessory Parotid Tissue

Accessory parotid tissue is most commonly located anterior to the parotid gland, along the course of the parotid or Stensen duct (see Fig. 22.2). As judged by anatomic dissection, about 20% of human parotid glands manifest accessory tissue. Accessory parotid glands have been described as either round or triangular in shape, and almost all contain anastomoses of the zygomatic and buccal branches of the facial nerve within their substance. Although this tissue is susceptible to most salivary pathology, tumors of the accessory parotid gland are more frequently malignant than those of the parotid gland.

Surgical Anatomy of the Submandibular Gland

The submandibular gland consists of a large superficial lobe lying within the digastric triangle in the neck and a smaller deep lobe lying within the floor of the mouth posteriorly. The two lobes are continuous with each other around the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle. The two lobes are not true lobes, as they are embryologically the same gland arising from a single epithelial outgrowth. The gland is a mixed seromucinous gland.

The Superficial Lobe

The Superficial Lobe

The superficial lobe of the submandibular gland lies within the digastric triangle. Its anterior pole reaches the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the posterior pole reaches the stylomandibular ligament. Superiorly, the superficial lobe lies medial to the body of the mandible. Inferiorly, it often overlaps the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscles and the insertion of the stylohyoid. The lobe is partially enclosed between the two layers of the deep cervical fascia that arises from the greater cornu of the hyoid bone and is intimately related to the facial vein and artery. The superficial layer of the fascia is attached to the lower border of the mandible and covers the inferolateral surface of the superficial lobe. The deep layer of fascia is attached to the mandible and covers the medial surface of the lobe. The inferolateral surface, which is covered with skin, subcutaneous fat, platysma, and the deep fascia, is crossed by the facial vein and the cervical branch of the facial nerve, which loops down from the angle of the mandible and innervates the lower lip. The submandibular lymph nodes lie between the salivary gland and the mandible.

The lateral surface of the superficial lobe is related to the submandibular fossa, a concavity on the medial surface of the mandible, and the attachment of the medial pterygoid muscle. The facial artery grooves its posterior part, lying at first deep to the lobe and then emerging between its lateral surface and the mandibular attachment of the medial pterygoid muscle, from which it reaches the lower border of the mandible.

The medial surface is related anteriorly to the mylohyoid, from which it is separated by the mylohyoid nerve and submental vessels. Posteriorly, it is related to the styloglossus, the stylohyoid ligament, and the glossopharyngeal nerve separating it from the pharynx. Between these, the medial aspect of the lobe is related to the hyoglossus muscle, from which it is separated by the styloglossus muscle, the lingual nerve, and the deep lingual vein. More inferiorly, the medial surface is related to the stylohyoid muscle and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

The Deep Lobe

The Deep Lobe

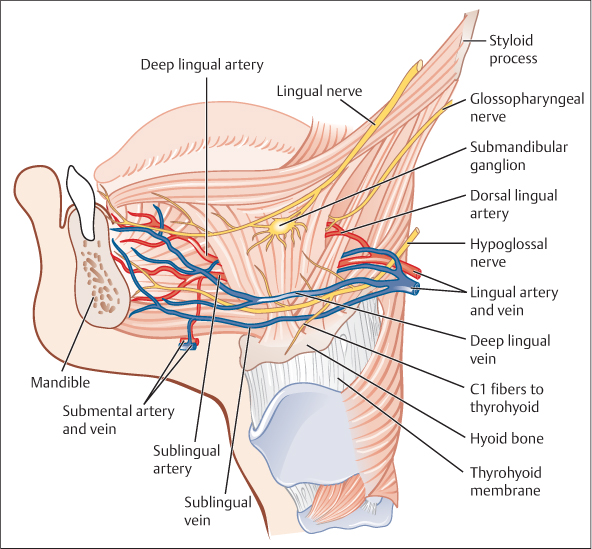

The deep lobe of the submandibular gland joins the superficial lobe at the posterior free edge of the mylohyoid muscle and extends forward to the back of the sublingual gland. It lies between the mylohyoid muscle inferolaterally, the hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles medially, the lingual nerve superiorly, and the hypoglossal nerve and the deep lingual vein inferiorly (Fig. 22.5).

The Submandibular Duct

The Submandibular Duct

The submandibular duct is about 5 cm long in an adult. The wall of the duct is thinner than that of the parotid duct. It arises from numerous tributaries in the superficial lobe and emerges from the medial surface of this lobe just behind the posterior border of the mylohyoid. It passes through the deep lobe, passing upward and slightly backward for 5 mm before running forward between the mylohyoid and the hyoglossus muscles. As it passes forward, it runs between the sublingual gland and genioglossus to open into the floor of the mouth on the summit of the sublingual papilla at the side of the lingual frenum just below the tip of the tongue. It lies between the lingual and hypoglossal nerves on the hyoglossus muscle. At the anterior border of the hyoglossus muscle, it is crossed by the lingual nerve.

Fig. 22.5 Dissection of the submandibular gland bed, illustrating the lingual nerve, and the hypoglossal nerve lying on the hyoglossus muscle (the mylohyoid muscle is not shown).

Surgical Anatomy of the Sublingual Gland

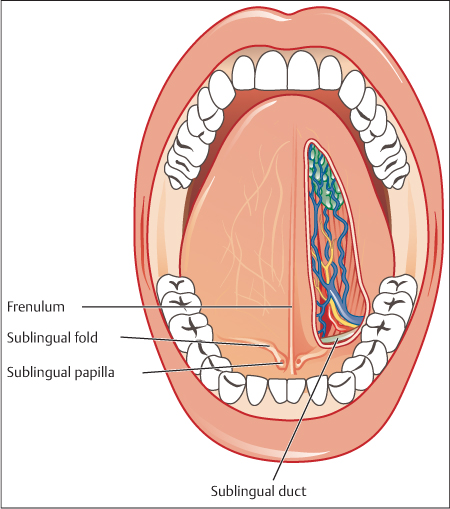

The sublingual gland is the smallest of the major salivary glands (Fig. 22.6). It is almond-shaped or tadpole-shaped. The head of the tadpole lies in the anterior floor of the mouth, and the tail runs back in the salivary gutter toward the submandibular gland. The shape of the head is oval, but in the depth it is wedge-shaped, running down on the mylohyoid to its attachment on the mandible. It is predominantly a mucous gland. The gland lies on the mylohyoid and is covered by the mucosa of the floor of the mouth, which is raised as it overlies the gland to form the sublingual fold. Posteriorly, the sublingual gland is in contact with the deep lobe of the submandibular gland. The sublingual fossa of the mandible is located laterally, and the genioglossus muscle is located medially. The lingual nerve and the submandibular duct lie medially to the sublingual gland between it and the genioglossus. They are unencapsulated glandular tissue nests. Tumors of the sublingual gland are very rare, and the majority are malignant. Bimanual palpation of the floor of the mouth is a reliable method of assessing the local extent of the tumor. Small tumors less than 2 cm can usually be excised transorally, but larger tumors usually require a more substantive locoregional resection.

Fig. 22.6 The anterior floor of the mouth, illustrating the submandibular duct and the relationship of the lingual nerve and vessels. These are located deep and superior to the sublingual gland, which is located submucosally.

Surgical Anatomy of the Minor Salivary Glands

Minor salivary glands are distributed widely in the submucosa of the head and neck region, and are most frequently found in the oral cavity and oropharynx. They are grouped according to their anatomic location—labial, buccal, palatoglossal, palatal, tonsillar, etc. They have mixed functions; the labial and buccal glands are both serous and mucous, whereas the palatoglossal glands are mucus-secreting.

Indications and Patient Selection

Surgery is the standard treatment for any kind of benign epithelial salivary gland neoplasm. Alternative treatments, in the form of conservative treatment or injection of sclerotics, are only available for vascular malformations (see Chapters 10 and 11).

Several techniques for parotid surgery have been described and are presented in this chapter. They have different but sometimes overlapping indications:

Lateral or superficial parotidectomy is a surgical procedure that excises the parotid salivary tissue that lies lateral to the plane of the facial nerve and its branches.

Lateral or superficial parotidectomy is a surgical procedure that excises the parotid salivary tissue that lies lateral to the plane of the facial nerve and its branches.

Partial lateral or superficial parotidectomy is a technique in which small benign tumors (less than 4 cm) located in the lateral lobe of the parotid gland are resected with a cuff of normal tissue. It is reported that such operations result in fewer complications.7 More recently, a procedure described as endoscopy-assisted partial superficial parotidectomy has been performed in 30 patients, with no recurrences reported after a follow-up period of 26–50 months.8

Partial lateral or superficial parotidectomy is a technique in which small benign tumors (less than 4 cm) located in the lateral lobe of the parotid gland are resected with a cuff of normal tissue. It is reported that such operations result in fewer complications.7 More recently, a procedure described as endoscopy-assisted partial superficial parotidectomy has been performed in 30 patients, with no recurrences reported after a follow-up period of 26–50 months.8

Extracapsular dissection (ECD) of parotid tumors is controversial and is only recommended and advocated by a few specialists, the majority of whom have been in surgical practice for many years and are able to perform the full range of parotid surgery when indicated.9–12 In general, the patients have a small parotid mass with clinical findings showing that it is laterally freely mobile and with FNAC findings confirming a benign neoplasm of salivary origin.

Extracapsular dissection (ECD) of parotid tumors is controversial and is only recommended and advocated by a few specialists, the majority of whom have been in surgical practice for many years and are able to perform the full range of parotid surgery when indicated.9–12 In general, the patients have a small parotid mass with clinical findings showing that it is laterally freely mobile and with FNAC findings confirming a benign neoplasm of salivary origin.

Transcervical and transcervical/parotid approaches are reserved for deep lobe parotid tumors located in the retromandibular region and parapharyngeal spaces. This technique is performed after elevation with or without removal of the lateral lobe of the parotid gland. For the transcervical/parotid approach, the tumor is dissected free from the branches of the facial nerve using a fine hemostat or scissors, with bipolar coagulation. Careful handling of the deep lobe parotid tissue and the capsule of the tumor will reduce the risk of rupture. There is evidence suggesting that benign tumors of the parapharyngeal space have thicker capsules than similar tumors located in the lateral parotid lobe.13 A higher rate of temporary and permanent palsy can be expected after surgery in this area. A radiological classification has been suggested for tumors of the deep lobe of the parotid, which recommends a surgical approach based on whether the tumor is in a prestyloid or retrostyloid location on computed tomography (CT) and on its relationship to the pterygoid plates.14

Transcervical and transcervical/parotid approaches are reserved for deep lobe parotid tumors located in the retromandibular region and parapharyngeal spaces. This technique is performed after elevation with or without removal of the lateral lobe of the parotid gland. For the transcervical/parotid approach, the tumor is dissected free from the branches of the facial nerve using a fine hemostat or scissors, with bipolar coagulation. Careful handling of the deep lobe parotid tissue and the capsule of the tumor will reduce the risk of rupture. There is evidence suggesting that benign tumors of the parapharyngeal space have thicker capsules than similar tumors located in the lateral parotid lobe.13 A higher rate of temporary and permanent palsy can be expected after surgery in this area. A radiological classification has been suggested for tumors of the deep lobe of the parotid, which recommends a surgical approach based on whether the tumor is in a prestyloid or retrostyloid location on computed tomography (CT) and on its relationship to the pterygoid plates.14

The mandibulotomy approach is not usually required even for large benign tumors, and is only indicated when the diagnosis is uncertain (e.g., paraganglioma) or for recurrent benign tumors. A paramedian or median mandibulotomy is the preferred route of access to tumors in the parapharyngeal space. Recently, other techniques have been described using a lateral mandibulotomy or a visor approach, avoiding division of the lip.15,16

The mandibulotomy approach is not usually required even for large benign tumors, and is only indicated when the diagnosis is uncertain (e.g., paraganglioma) or for recurrent benign tumors. A paramedian or median mandibulotomy is the preferred route of access to tumors in the parapharyngeal space. Recently, other techniques have been described using a lateral mandibulotomy or a visor approach, avoiding division of the lip.15,16

Accessory parotidectomy is indicated for benign lesions that are clinically palpable along the Stensen duct, separate from the parotid tissue, or in close proximity to the periphery of the parotid tissue. Local incisions either on top of the tumor externally or tumor removal internally must generally be avoided. CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and FNAC must be performed before surgical excision begins.15

Accessory parotidectomy is indicated for benign lesions that are clinically palpable along the Stensen duct, separate from the parotid tissue, or in close proximity to the periphery of the parotid tissue. Local incisions either on top of the tumor externally or tumor removal internally must generally be avoided. CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and FNAC must be performed before surgical excision begins.15

Submandibular gland excision is appropriate only when investigations such as FNAC and CT/MRI suggest a benign tumor diagnosis.

Submandibular gland excision is appropriate only when investigations such as FNAC and CT/MRI suggest a benign tumor diagnosis.

Sublingual gland excision: the benign nature of swellings located in the anterior floor of the mouth has to be confirmed before excision.

Sublingual gland excision: the benign nature of swellings located in the anterior floor of the mouth has to be confirmed before excision.

Minor salivary gland excision surgery: the benign nature of the tumor has to be confirmed before excision.

Minor salivary gland excision surgery: the benign nature of the tumor has to be confirmed before excision.

The aim of surgical excision of benign salivary gland neoplasms is to remove the tumor with a sufficient margin of normal tissue to prevent recurrence, while avoiding neurological and vascular complications.

The aim of surgical excision of benign salivary gland neoplasms is to remove the tumor with a sufficient margin of normal tissue to prevent recurrence, while avoiding neurological and vascular complications.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses