Indications and Patient Selection

Submandibular and Sublingual Gland

Complications and Sequelae of Surgery

Anesthesia or Hypesthesia of the Skin

Measures for Specific Complications

Follow-Up after Curative Surgery

Introduction

In large series reported in the literature, about 25% of parotid gland tumors, 50% of submandibular gland tumors, and over 80% of neoplasms in the minor salivary glands were malignant. Eighty percent of malignant salivary gland tumors are located in the parotid glands.1–4 While the vast majority of head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, most parotid gland cancers arise from glandular epithelium. They can be categorized histologically as primary adenocarcinomas (with various subtypes). Tumors originating from glandular epithelium behave differently from squamous cell carcinomas. Many grow slowly over years, tumors can recur years after initial treatment, and the rate of distant metastasis during the natural history of the disease is high.5–7

In the past, the response to radiotherapy was considered to be unpredictable when treating salivary adenocarcinomas, but when tumors are inoperable, dramatic responses to radiotherapy have been reported. Surgery with complete excision of the tumor, with the surrounding salivary gland tissue and adjacent lymph nodes, therefore serves as a basis for curative treatment whenever surgery is possible.8–10

Salivary gland tumors differ in yet another way from other malignant head and neck neoplasms. Whereas a histological diagnosis is easily obtained in lesions located in the oral cavity, pharynx, or larynx, biopsy is usually contraindicated in major salivary gland lesions, due to the risk of tumor cell seeding and injuries to cranial and local nerves. Although aspiration cytology has been shown to be able to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions with a high degree of accuracy in many cases, distinguishing between cystadenolymphoma (Warthin tumor) and squamous cell carcinoma remains problematic, and reliable preoperative cytology is not universally available.11 Although improved imaging methods (magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and ultrasonography) have had a major impact on salivary gland surgery as a result of increased confidence in distinguishing benign from malignant tumors preoperatively, the risk of inadvertently encountering a malignant neoplasm during parotidectomy cannot yet be totally avoided. Since more major salivary gland tumors are now being detected at an earlier stage of disease than previously, the definitive diagnosis of a malignancy is frequently made only during or after surgery.

Indications and Patient Selection

While most patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck can now be offered a variety of therapeutic options, surgery remains the standard treatment for all salivary gland cancers. Radiation alone has not proved to be curative, except in a small number of individual patients, and no controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of concurrent chemoradiotherapy have so far been published (see Chapters 30 and 31). Treatment for salivary gland carcinomas therefore follows a fairly uniform pathway: surgery is clearly indicated as the initial treatment, aiming for complete removal of the tumor and preservation of the facial nerve when possible or with total or partial facial nerve sacrifice when indicated.8,10,12

Surgery still is the cornerstone of primary treatment for salivary gland cancer.

Surgery still is the cornerstone of primary treatment for salivary gland cancer.

Complex therapeutic decisions are now generally discussed in the framework of multidisciplinary cancer conferences, also known as multidisciplinary tumor boards or case conferences. Unfortunately, very few treatment options are often available for patients presenting with a salivary gland cancer; surgery is the considered the best treatment when cure is the likely goal. In many cases, surgery will already have been performed when the patient’s diagnosis of cancer is first being discussed at the tumor board. The only question to be discussed and decided is the final histological diagnosis and adverse pathological findings possibly associated with it, such as surgical margins, lymph-node involvement, tumor grade, perineural involvement, etc., which will suggest whether postoperative radiotherapy is indicated.

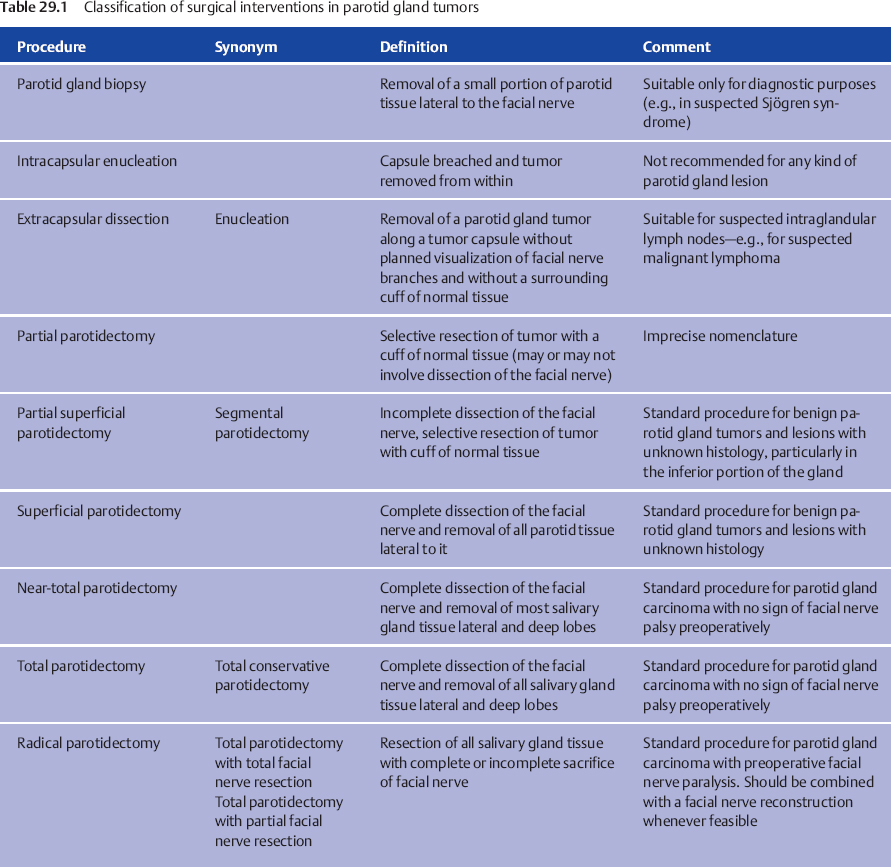

The key question in planning the surgical treatment for an individual patient is the anticipated extent of the resection that will be required to achieve excision with clear tumor margins and intraoperative management of the facial nerve. In spite of the vast variety of histological subtypes of salivary gland carcinomas, histology does not play a role in determining the extent of surgery. A classification of surgical procedures of the parotid gland and the corresponding nomenclature has been proposed by Tweedie and Jacob,13 and a suggested modified classification is presented in Table 29.1 (see also Chapter 22).

Choice of Surgical Procedure

Parotid Gland

Parotid Gland

Once a diagnosis of salivary gland carcinoma has been confirmed, the standard surgical procedure for parotid gland carcinoma will almost always be a total or subtotal parotidectomy. Lateral parotidectomy may be sufficient for small, superficial, low-grade malignant tumors with no evidence of lymph-node metastasis and/or nerve invasion, particularly if the tumor is located in the inferior portion of the gland. For patients presenting with facial nerve paralysis, however, radical parotidectomy is the only reasonable approach.14–19

If a diagnosis of malignant lymphoma is being considered and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the parotid gland might confirm the likely diagnosis, then a biopsy is sufficient for diagnosis, and further treatment will include chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, but not surgery. A strong suspicion of malignant lymphoma is the one rare exception to the “no biopsy in salivary gland tumors” rule and may obviate the need for more extensive surgery.

Subtotal or total parotidectomy is the standard surgical procedure for most parotid gland carcinomas. In patients in whom a mass is associated with facial nerve paralysis, radical parotidectomy is the only reasonable approach to achieve a cure.

Subtotal or total parotidectomy is the standard surgical procedure for most parotid gland carcinomas. In patients in whom a mass is associated with facial nerve paralysis, radical parotidectomy is the only reasonable approach to achieve a cure.

If a diagnosis of parotid gland carcinoma is made after partial parotid surgery for a probably benign tumor, then the aim should be to carry out total parotidectomy and this should be recommended to the patient as a completion procedure. This surgical revision should then remove the remaining salivary gland tissue along with the adjacent lymphatic structures, and surgery should be scheduled as early as possible, before the onset of scar formation and fibrosis, which make revision surgery with facial nerve preservation more difficult.

Facial Nerve

Facial nerve sacrifice is only required for patients with preoperative facial nerve paralysis. It is no longer routinely advocated if the nerve is functioning normally before surgery.16,20 Similarly, there is no place for “routine” resection of the mandibular branch of the facial and the lingual or hypoglossal nerves in surgery for submandibular gland carcinoma. If branches of the facial nerve are involved while others are not, it is sufficient to resect those that are infiltrated, leaving the main stem and the unaffected branches intact. In tumors that completely encase nerve branches, neural sacrifice is limited to the involved branches. Every effort to dissect the tumor away from the individual branches should be undertaken. There is no “all or nothing” rule with regard to facial nerve preservation during parotidectomy. Nerve grafting with the great auricular nerve, hypoglossal–facial nerve anastomosis, or a combination of these techniques is recommended at the end of ablative surgery to facilitate facial rehabilitation (see Chapter 38).

The facial nerve only has to be sacrificed if the nerve has been infiltrated. Only the infiltrated parts have to be resected and at best reconstructed directly. Otherwise, there is no need for facial nerve resection. As in benign salivary gland tumors, the aim of the operation is to preserve the facial nerve completely, or as much as possible, in patients with facial palsy.

The facial nerve only has to be sacrificed if the nerve has been infiltrated. Only the infiltrated parts have to be resected and at best reconstructed directly. Otherwise, there is no need for facial nerve resection. As in benign salivary gland tumors, the aim of the operation is to preserve the facial nerve completely, or as much as possible, in patients with facial palsy.

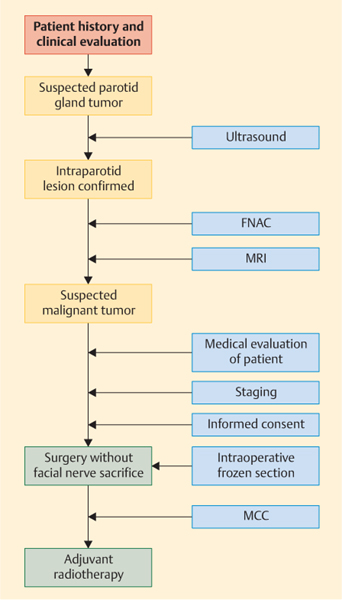

A simplified algorithm for planning the treatment of suspected malignant parotid gland tumors is given in Fig. 29.1.

Fig. 29.1 Algorithm for planning the treatment of suspected malignant parotid gland tumors. FNAC, fine-needle aspiration cytology; MCC, multidisciplinary cancer conference; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Other Salivary Glands

Other Salivary Glands

The standard treatment for submandibular gland carcinoma is complete excision of the gland and the surrounding lymphatic structures. For minor salivary gland carcinomas, preferably diagnosed with a punch biopsy or incisional biopsy, the same rules are recommended as in the surgical management of primary squamous cell carcinoma.21,22

Informed Consent

Informed consent is a medical and legal prerequisite for every type of elective surgical intervention. Consent is provided by the patient after the surgeon has given him or her comprehensive information about the illness, options for treatment, and associated risks. In practical terms, it should be a dialogue-based process of explanation and discussion in order to enhance patient autonomy and allow confident decision-making on a planned therapy. In parotidectomy, it is particularly difficult to discuss the treatment plan before surgery without knowing the histology of a given salivary gland tumor.

Surgical interventions aiming at the complete resection of salivary gland tumors carry a significant risk for surgery-related sequelae. Some of the decisions regarding the extent of surgery can only be taken during the course of the procedure. Patients therefore have to receive information about several topics before a final decision is taken on which treatment to choose and on treatment-related risks. As the decision may be complex in individual cases, it may be necessary to obtain informed consent in several consecutive steps. The topics to be discussed in this setting are briefly summarized in Table 29.2.

Anesthesia and Positioning

Although parotidectomy and excision of the submandibular gland can be performed with the patient under local anesthesia, the procedures are usually best carried out with general anesthesia. Since local anesthesia would interfere with the excitability of the facial nerve, identification and preservation of the nerve and its branches would be hampered by infiltration with local anesthetics. Many experienced surgeons would therefore consider it inappropriate to carry out these procedures with local anesthesia. Superficial infiltration of skin and subcutaneous tissue with 1% lidocaine (containing epinephrine) is customary and is used to reduce bleeding during the skin incision and raising of the skin flap.

Although the patient undergoes general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation, anesthesiologists must refrain from using paralyzing agents, as these may make nerve monitoring impossible.

|

Rationale for surgery |

|

Specific medical conditions and risk factors of individual patient |

|

Preoperative imaging—requirements and findings |

|

Preoperative fine-needle aspiration cytology and/or intraoperative frozen sections |

|

Alternative options to surgery |

|

Possible consequences if the patient declines surgery |

|

Surgical approach—anticipated and possible alternatives |

|

Recommended surgical equipment (nerve monitoring, operating microscope) |

|

Extent of surgery (facial nerve sacrifice and reconstruction, neck dissection) |

|

Nerve reconstruction if needed, and the expected outcome |

|

Risks and possible sequelae of surgery: |

|

|

|

Postoperative care |

|

Risk of local, regional, and distant recurrence |

|

Indications for postoperative radiotherapy |

|

Long-term posttreatment surveillance |

The patient is placed in a supine position. The head is turned away from the affected side and elevated slightly to reduce venous congestion. After electrodes have been placed for nerve monitoring, the surgical area is prepared and draped. The face is left exposed by placing a transparent dressing to allow facial movements to be observed during surgery. Using an operating microscope or magnifying glasses during surgery is mandatory at the authors’ institutions.

Surgical Steps

Parotid Gland

Parotid Gland

When planning surgery of a malignant tumor of the parotid gland, the following goals should be considered:

Complete and secure removal of the neoplasm within clear margins

Complete and secure removal of the neoplasm within clear margins

Preservation of facial nerve function

Preservation of facial nerve function

Or, if that is not possible, immediate nerve grafting and functional restoration of the denervated face

Or, if that is not possible, immediate nerve grafting and functional restoration of the denervated face

Or, if that is not possible, immediate static suspension plasty, with implantation of lid weights

Or, if that is not possible, immediate static suspension plasty, with implantation of lid weights

Thus leading to acceptable aesthetic results

Thus leading to acceptable aesthetic results

Parotid gland and facial nerve surgery should therefore always be performed using a microscope or loupe magnification glasses to prevent injuries to nerves or tumor capsule. Large series have shown that standard surgical procedures lead to better results in terms of clear tumor margins and postoperative facial nerve function than approaches with too much individual adaptation.23 When malignant tumors are being removed, it is obvious that standard surgical procedures often have to be abandoned in order to ensure complete tumor removal. However, we would recommend carrying out surgery for malignant parotid gland tumors as close as possible to the following, well-defined surgical approaches.

Local Tumor Enucleation

Local tumor enucleation should be avoided for many reasons—the most important being that the sentinel lymph nodes of malignant parotid gland tumors are usually located within the lymph system of the parotid gland itself. They have to be removed to prevent local recurrence.24

Lateral or Superficial Parotidectomy

This is a minimal form of surgical intervention for malignant parotid tumors and should only be considered as the first step or initial approach for any form of extended parotid gland surgery. Superficial parotidectomy as the sole approach is strictly limited to patients in whom there is no likelihood of intraparotid lymph node metastasis (see Chapter 22).

Anterograde and Retrograde Identification of the Facial Nerve Trunk

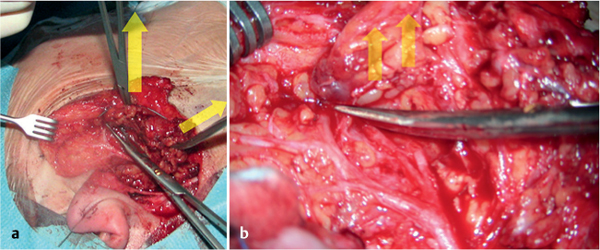

In most cases, malignant lesions allow a standard incision (Fig. 29.2) and exposure of the facial nerve trunk with no risk of damaging the tumor margins (Fig. 29.3); this may not be possible if the tumor is located close to the stylomastoid foramen. In these cases, and if the facial nerve is enclosed in the tumor close to its trunk or bifurcation, it may be necessary to change the surgical approach from an anterograde to a retrograde approach to identify the facial nerve.

Fig. 29.2 A typical incision, 2 weeks after surgery for hemangiosarcoma of the parotid gland.

Fig. 29.3 a, b During dissection, the superficial part of the parotid gland is tensed laterally (a) and the scissors dissect the parotid tissue at the level of the facial nerve branches (b). The arrows indicate lines of tension.

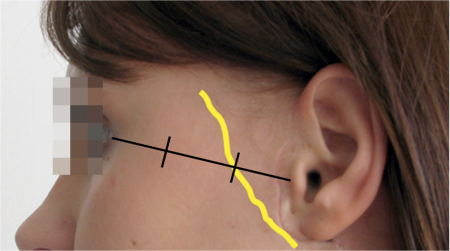

Fig. 29.4 The frontal branch of the facial nerve is located on the zygomatic arch, at the first third of a line connecting the tragus and the lateral canthus.

This is followed by exposure of the frontal branch of the facial nerve, which can be located and identified in the first third of a line between the tragus and the lateral canthus. The subcutaneous fat on the zygomatic arch is spread perpendicularly until the nerve branch and its accompanying vessel become visible (Fig. 29.4). The facial nerve branch is dissected retrogradely toward the bifurcation until the next branch becomes visible, and so on, so that the superficial parotid gland lobe is dissected as a whole.

Total Parotidectomy

Most malignancies of the parotid gland should be treated with total parotidectomy.

Total parotidectomy includes resection of the intraparotid gland lymph nodes, as these are the sentinel lymph nodes for any parotid gland malignancy. They should always be removed to allow histological examination. Total parotidectomy is necessary for most malignant parotid gland tumors, and especially for tumors extending into the deep parotid lobe or when the tumor primarily arises in the deep lobe (Fig. 29.5). Removal of the deep lobe requires identification and protection of the facial nerve, as mentioned above (see lateral or superficial parotidectomy, Chapter 22).

The dissection borders are:

Medially: the digastric and stylohyoid muscle, styloid process, internal carotid artery

Medially: the digastric and stylohyoid muscle, styloid process, internal carotid artery

Dorsally: the sternocleidomastoid muscle, cranial nerve XII

Dorsally: the sternocleidomastoid muscle, cranial nerve XII

Cranially: ear cartilage and skull base

Cranially: ear cartilage and skull base

Ventrally: the ascending mandibular and adjacent muscles (masseter and pterygoid muscles)

Ventrally: the ascending mandibular and adjacent muscles (masseter and pterygoid muscles)

Caudally: cervical lymph nodes, depending on the extent of neck dissection

Caudally: cervical lymph nodes, depending on the extent of neck dissection

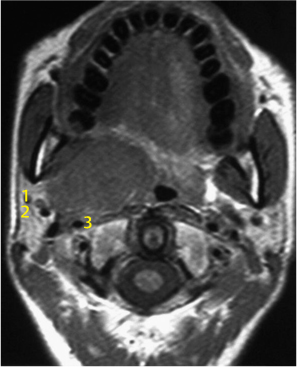

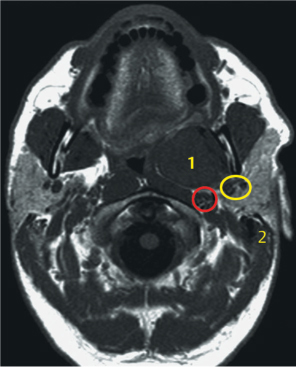

Deep lobe parotid gland resection is difficult, as the retromandibular space is crossed by larger vessels (the maxillary artery and retromandibular vein), which have to be ligated and cut (Fig. 29.6). The retromandibular space is limited medially by the styloid process; tumors that extend even further into the pterygoid fossa need a larger approach, to ensure that the internal carotid artery is not damaged and to preserve the hypoglossal and hypopharyngeal nerves.

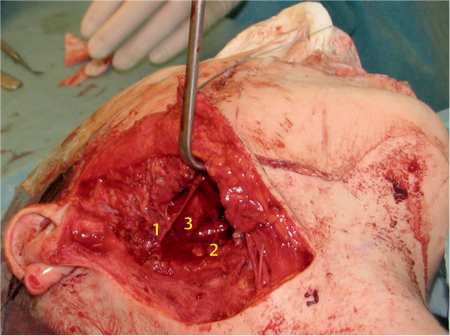

Fig. 29.5 A large parotid gland tumor (basal cell adenocarcinoma) emerging from the deep lobe of the gland. The retromandibular vein (1), maxillary 1 artery (2), and 2 carotid artery (3) 3 are located lateral to the tumor.

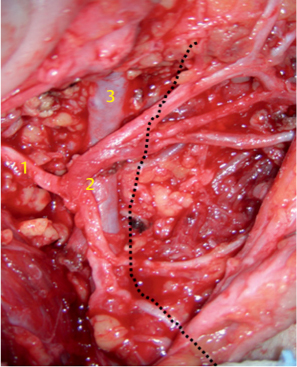

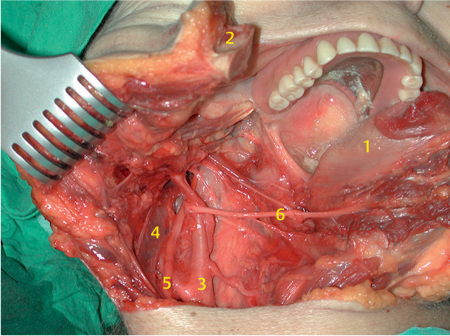

Fig. 29.6 The facial nerve fan and the retromandibular vein are in close vicinity to each other; 1, stem; 2, bifurcation, 3, retromandibular vein. The dotted line indicates the mandible.

Radical Parotidectomy

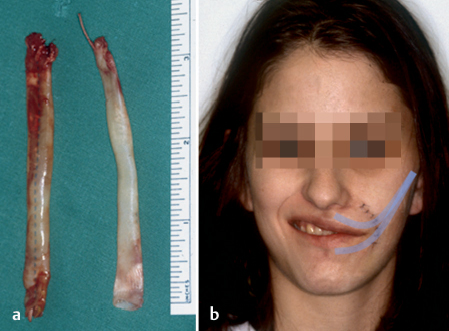

Radical parotidectomy is complete resection of the parotid gland, with resection of the facial nerve or parts of it. Radical parotidectomy should only be performed when tumor invasion into the facial nerve has been confirmed functionally (facial nerve palsy) or histologically (Fig. 29.7), or in cases in which the tumor is completely encasing the nerve branches. Whereas in the past surgeons proposed complete resection of the facial nerve even in patients with no confirmed tumor involvement of the nerve, nowadays the policy is to preserve the facial nerve as far as possible but to strive to achieve clear surgical margins around the tumor.16,25 This is because locoregional tumor recurrence causes fewer problems than distant metastatic disease, especially in well-differentiated malignant tumors such as adenoid cystic carcinoma.26,27

Fig. 29.7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) with intraneural spread into the facial nerve stem. Hematoxylin–eosin staining, oblique section; 1, neuron; 2, perineurium; 3, ACC.

In cases in which the tumor extends close to the nerve, the nerve may be peeled off the tumor and the patient can receive postoperative radiotherapy. Although this procedure transgresses against the classic oncological principle that malignant tumors should be resected with a wide margin, high rates of survival confirm the efficacy of postoperative radiotherapy in eradicating microscopic remnants of tumor after surgery.28 If branches of the facial nerve have to be removed, immediate nerve grafting (for more details, see Chapter 38) using the great auricular nerve or sural nerve has been shown to be feasible and successful in the majority of patients.29 However, since facial nerve function will recover within about 6 months even after successful grafting, closure of the eye should be ensured early after facial nerve sacrifice by implanting lid weights to prevent conjunctival damage (Fig. 29.8).

The angle of the mouth can also be restored with cautious static suspension plasty with fascia lata (Fig. 29.9). Surgery has to be performed extremely carefully, and facial nerve branches that might be reinnervated later on should not be damaged.

Occasionally, patients may require extended parotidectomy, which includes resection of the masseter muscle or parts of the ascending portion of the mandible. This can be combined with a transzygomatic approach to the infratemporal fossa and cranial base to clear perineural spread of tumor along the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V3) and involvement of the pterygoid muscles in the infratemporal fossa. Patients who have trismus, decreased masseter contraction, or jaw shift to the affected side preoperatively are likely to require extended-type procedures for complete tumor clearance.

Fig. 29.8 a, b A platinum chain weight implant in a patient with high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland and complete resection of the facial nerve stem with hypoglossal–facial nerve anastomosis. The position of the platinum chain weight is shown in b.

Fig. 29.9 a, b Static suspension plasty of the angle of the mouth in a 17-year-old patient with transient facial nerve palsy after tumor surgery and nerve cable grafting. Autologous fascia lata was used. The shaded lines indicate the position of the fascia lata.

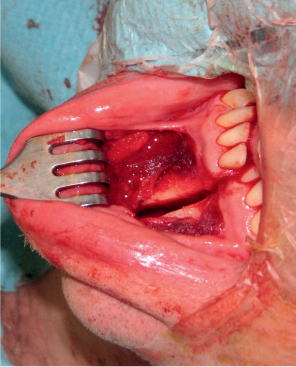

Transoral Approach

Most neoplasms of the parapharyngeal space can be resected successfully with either a parotid or a transcervical–parotid approach. In patients with extended disease, these approaches do not provide adequate access to the parapharyngeal space, and enhanced exposure is needed to allow complete tumor removal without rupture of the capsule and spillage (Fig. 29.10). In these cases, some authors recommend an isolated transoral approach. This allows only limited access to the parapharyngeal space. Moreover, this approach may be hazardous and cause tumor spillage and spread, as well as damage to the parapharyngeal nerves (cranial nerves VII, IX, X, and XII) and vessels (the jugular vein and inner carotid artery). Various mandibulotomy techniques have so far been described for these patients.30,31

Fig. 29.10 A T1-weighted magnetic resonance image in a 40-year-old man with carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in the inner lobe of the parotid gland; 1, squamous cell carcinoma; 2, mastoid. The yellow circle indicates the retromandibular vein and maxillary artery, and the red circle indicates the carotid artery.

Fig. 29.11 A 28-year-old woman after a covert mandibular swing procedure. The typical parotidectomy incision has been extended anteriorly.

Fig. 29.12 Mandibular osteotomy, with preservation of the soft tissue of the chin.

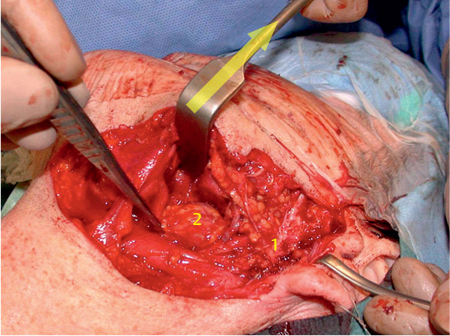

Fig. 29.13 The mandible is flexed strongly superiorly, with preservation of the inferior alveolar nerve, allowing access to the tumor; 1, facial nerve; 2, tumor. The yellow arrow indicates the direction of tension.

Covert Mandibular Swing

The advantages of the covert technique are that it avoids a cheek and lip scar and a connection between the infectious oral cavity and the large resection wound.

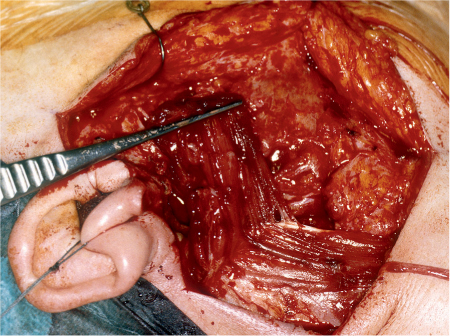

Lateral parotidectomy has to be performed to ensure identification and preservation of the facial nerve. The standard cervical incision, placed in an upper neck crease, needs to be extended medially to the mental foramen region (Fig. 29.11). Through a second, intraoral approach, the buccal and lingual gingiva are reflected inferiorly for about 5 mm at the planned osteotomy site.

Subperiosteal dissection is performed for exposure of the symphysis of the mandible, providing adequate space to use the reciprocating saw to create the osteotomy (Fig. 29.12). This avoids the need for a skin incision. The anterior osteotomy starts at the inferior edge of the mandible. To avoid damage to adjacent tooth roots, the osteotomy is performed exactly perpendicularly in the symphysis of the mandible, thus avoiding exposure of the mental nerve as well as of the incisor alveoli. A thin horizontal mark is sawn into the mandible to allow precise adjustment of the compression miniplates after tumor removal, thus preventing malocclusion. The mandible is then flexed strongly superiorly, with preservation of the inferior alveolar nerve, allowing access to the tumor (Fig. 29.13)

The parapharyngeal space opens wide, and even large tumors of the deep lobe of the parotid gland can be removed without damage to the tumor capsule and with preservation of cranial nerves VII, IX, X, and XII, and the large vessels (Fig. 29.14). Rigid fixation of the branches of the mandible is achieved using double compression plates at the osteotomy site.32

Fig. 29.14 After tumor removal, the nerves and vessels in the skull base become visible; 1, facial nerve fan; 2, jugular vein; 3, skull base.

Fig. 29.15 a, b Postoperative cosmetic result following lower lip split mandibular swing procedure.

a One year after procedure, no scarring is visible.

b Two years after procedure for a giant pleomorphic adenoma, the broken line and lip split incision are barely visible.

Fig. 29.16 A large lateral overview of the skull base after a conventional mandibular swing procedure in a cadaver dissection; 1, tongue; 2, right branch of the mandible; 3, carotid artery; 4, jugular vein; 5, vagal nerve; 6, hypoglossal nerve.

Fig. 29.17 Computed tomography of the mandible 2 weeks after mandibulotomy. The dynamic miniplates and very thin saw split are visible.

Open Mandibular Swing

Very large parotid tumors extending to the skull base and the pterygoid fossa may need an even more extended approach. For this procedure, the soft tissue of the chin has to be transected, as well as the floor of the mouth with the mylohyoid muscle and the digastric muscle. The skin incision on the chin should be made with the broken line technique and a skip incision on the lip to ensure favorable aesthetic results (Fig. 29.15).33 The mandible is then rotated laterally and cranially and opens wide, providing an overview of the tumor, the pterygoid fossa, and the skull base with the descending vessels and nerves (Fig. 29.16).

Another advantage of the open mandibular swing approach is that it makes it slightly easier to reconstruct pharyngeal defects. A defect in the oropharyngeal wall caused by the resection is easily closed using an infrahyoidal muscle flap or a radial forearm flap. The floor of the mouth is then sutured layer by layer as usual. It has been shown in large series of patients that the mandibular joint usually recovers without any functional disturbance (Fig. 29.17).

Reconstruction

Total parotid gland resection usually leaves an aesthetically unfavorable indentation or “divot” between the ear and cheek. In addition, Frey syndrome develops after 10–12 months in up to 30% of the operated patients (see Chapter 39). Both of these sequelae can be avoided to some extent by using local or distant free grafts, such as a sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) graft or a free abdominal fat graft.34,35 The argument that tissue transfer may disguise tumor recurrences has been losing its importance with the advent of modern high-quality imaging methods—ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/CT.

The local sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle rotation flap is easily created, as the anterior SCM has usually already been skeletonized. Cranial nerve XII (the hypoglossal nerve) is then identified at the posterior and inferior border of the digastric muscle and followed to the SCM. Muscle cranial and lateral to the accessory nerve is mobilized and rotated anteriorly and superiorly, with care being taken to preserve the mastoid attachment and occipital artery blood supply to the muscle (Fig. 29.18). The morbidity associated with this flap is minimal provided that the spinal accessory nerve is protected.

Fig. 29.18 A sternocleidomastoid muscle rotation flap.

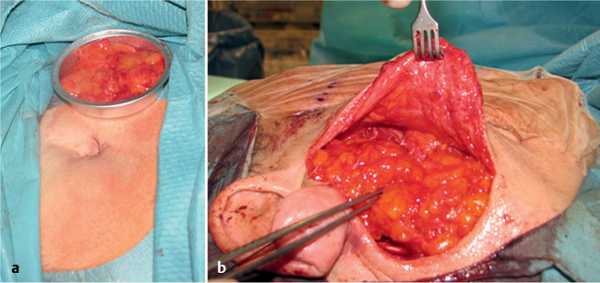

Free abdominal fat grafts have been advocated for many years for filling the parotidectomy defect.34 Some subcutaneous abdominal fat is lifted with a periumbilical incision and implanted into the parotid region in its natural form as a free graft. The volume of fat grafted into the hole should be slightly larger than the amount removed, as about one-third of the fat will degenerate. The free fat graft is covered with gentamicin-containing collagen tissue to prevent infection (Fig. 29.19). A pressure bandage is then gently applied to the abdomen wound area for 2–3 days.

Submandibular and Sublingual Gland

Submandibular and Sublingual Gland

Tumors of the submandibular gland require complete excision of the gland (see Chapter 22). The typical approach is a transcervical incision two fingerbreadths below the mandible in a line of relaxed skin tension. The inferior border of the gland is identified during elevation of a subplatysmal flap. The anterior facial vein is clamped, ligated, and retracted superiorly along with marginal mandibular nerve branches. It is sometimes necessary to mobilize these branches completely. This plane of dissection is continued until the mandible is encountered.

The facial vessels may be clamped and ligated at the inferior border of the mandible or dissected from the submandibular gland and preserved. Preglandular and post-glandular lymph nodes are sampled as part of the level II a neck dissection. Dissection then continues along the anterior belly of the digastric and mylohyoid muscle. The mylohyoid neurovascular supply is clamped and ligated, and the muscle is retracted anteriorly with a right-angled retractor. The lingual nerve and hypoglossal nerves are identified. The parasympathetic ganglion emanating from the lingual nerve is sacrificed, as is the submandibular duct, which is found between the hypoglossal and lingual nerves.

Fig. 29.19 a, b Transferring free fat tissue from a periumbilical incision provides fairly good aesthetic results and appears to prevent Frey syndrome.

Minor Salivary Glands

Minor Salivary Glands

Minor salivary gland tumors may occur anywhere in the upper aerodigestive tract. The most frequent location is in the soft and hard palate. Frequently, the lesions are not recognized as salivary gland tumors on first inspection, and the correct diagnosis is only made histologically. If they arise in the palate region, they are managed with transoral excision. If resection of parts of the hard palate is expected, molds of the palate should be taken before surgery to allow immediate placement of a prosthetic obturator. At a later stage, the patient and surgeon can decide whether the defect should be closed with a local or distant flap. The resection often has to be extended to include partial or total maxillectomy. Other minor salivary gland malignancies are addressed on a site-by-site basis, depending on their location.

Tips and Tricks

Tips and Tricks

During surgery, the patient should be in a supine position with the head up and rotated to the opposite side, with the feet down to reduce bleeding.

During surgery, the patient should be in a supine position with the head up and rotated to the opposite side, with the feet down to reduce bleeding.

Swabs should be saturated with 0.9% sodium chloride to reduce bleeding

Swabs should be saturated with 0.9% sodium chloride to reduce bleeding

If no neck dissection is planned, the posterior branch of the great auricular nerve should be preserved to prevent or reduce ear anesthesia or insensitivity.

If no neck dissection is planned, the posterior branch of the great auricular nerve should be preserved to prevent or reduce ear anesthesia or insensitivity.

The facial nerve appears to be more sensitive to compression than to tension and should not be tweezed.

The facial nerve appears to be more sensitive to compression than to tension and should not be tweezed.

Using Sulmycin Implant E (gentamicin) collagen sponges to cover the free fat transplant appears to reduce the rate of infection.

Using Sulmycin Implant E (gentamicin) collagen sponges to cover the free fat transplant appears to reduce the rate of infection.

Stripping of the Warthin duct prevents subsequent infection and development of stones in the salivary duct stump.

Stripping of the Warthin duct prevents subsequent infection and development of stones in the salivary duct stump.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Facial nerve injury with permanent or temporary and complete or partial loss of function, cosmetic effect on the face

Facial nerve injury with permanent or temporary and complete or partial loss of function, cosmetic effect on the face Possible injury to lingual nerve, hypoglossal nerve, accessory spinal nerve

Possible injury to lingual nerve, hypoglossal nerve, accessory spinal nerve Anesthesia/hypesthesia of the skin related to injury to the great auricular nerve

Anesthesia/hypesthesia of the skin related to injury to the great auricular nerve Hemorrhage, possible need for blood transfusion, postoperative intensive care

Hemorrhage, possible need for blood transfusion, postoperative intensive care Wound infection and wound breakdown

Wound infection and wound breakdown Salivary fistula and wound discharge

Salivary fistula and wound discharge Resultant scar and possibility of keloid development

Resultant scar and possibility of keloid development Gustatory sweating (Frey syndrome)

Gustatory sweating (Frey syndrome) Pain in face and neck

Pain in face and neck