The nose is the most frequently traumatized structure on the face due to its prominent central location and its elevation from the relatively flat frontal facial plane. The composite osteocartilaginous structure and its complex interconnections make the nose easily deformed when exposed to blunt trauma. Primary treatment of traumatic nasal deformities is presented in Chapter 13 . Secondary nasal reconstruction is not rare because of the high incidence of persistent deformities after primary treatment. Some authors have reported a very high failure rate, up to 80%, mainly due to failure to correct the septum, not just in the immediate postoperative period but over a longer time.

There are numerous reasons for the high incidence of secondary deformities of the nose after trauma. These include inadequate initial treatment due to a failure to appreciate the deranged anatomy, unstable bony and cartilaginous anatomy due to fracture lines and dislocations, insufficient postoperative stabilization, delayed presentation for treatment, and recurrent trauma in the early postoperative period. Regardless of the reason, patients need to be informed of the potential need for secondary rhinoplastic surgery after any nasal injury.

Secondary nasal deformities are associated with a variety of cosmetic and functional issues. Typically, the nose is deviated or depressed or both. Nasal breathing is often impaired, usually by being unilateral on the side of the deviation. Surgical correction of such nasal deformities can present some of the most difficult challenges in rhinoplasty. This chapter discusses the various deformities that may be found and some common techniques for their correction.

Anatomical Deformities And Evaluation

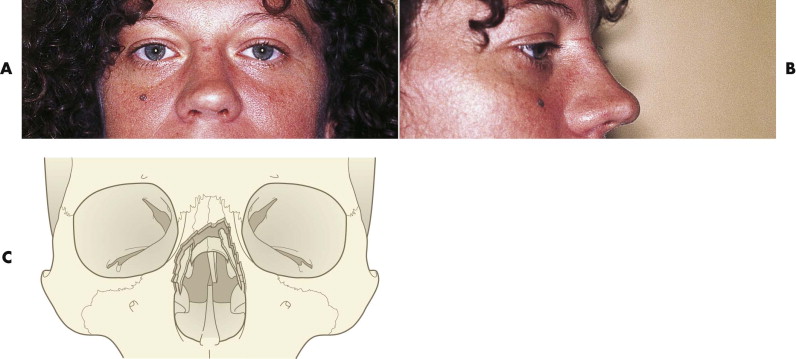

The effects of trauma to the nose and central face have been well described. With initial low-velocity trauma, the nasal tip alone can become malpositioned. Typically, the lower portion of the fracture rotates inward and the upper portion is pushed upward and outward. This action causes a supratip depression with a small, more cephalic hump ( Fig. 26-1 ). With increasing force, the cartilaginous and bony dorsum becomes fractured. Often, however, there is an incomplete fracture, which leads to a late deviation. This is frequently confused with a dislocation of the septum from the groove in the palatal shelf.

Clinical Examination

With experience and careful examination, it is possible to evaluate the external deformity and understand the underlying structural deformity. However, it is important to have a logical approach to the clinical examination of the nose. The variables are

- •

symmetry

- •

depression of the nasal dorsum

- •

tip deformity

- •

nasal skin scars

- •

condition of the internal septal and inferior turbinate

Symmetry

Asymmetry of the face is very common, and examination of the nose for asymmetry must be undertaken in context with the whole face. Pre-injury photographs are important to exclude long-standing asymmetry. Nasal symmetry is best assessed by looking from above the patient, with the head tilted back. This allows the nasal form to be examined afresh, with the eyebrows and chin point as reference points. Once these key landmarks have been evaluated, the cupid’s bow of the upper lip can be brought into the visual field by further tilting and related to the nasal tip. In many cases, the symmetry varies along the length of the nose, and this should be noted. Deviation of the upper third of the nose most likely reflects nasal bone deformation, deviation in the lower two thirds reflects the symmetry of the septum. This should give a clear understanding about the extent and position of any asymmetry. The columella should be examined from below to confirm any tip deviation and symmetry of the nares and domes. Finally, the nasal spine should be palpated. Traumatic displacement of the nasal spine can make true central alignment of the nose impossible.

Depression Of The Nasal Dorsum

To appreciate the position of the nasal bridge or dorsum, both lateral and anterior views must be evaluated. Laterally, the nose should come off the nasion and frontal bone at an angle of about 135 degrees. This line should continue until the slight rise at the nasal tip, to give the characteristic tip break. The columella should make an angle with the upper lip of 90 to 110 degrees. From these normal values, an appreciation of the defect should be possible, allowing appropriate planning, such as how much nasal augmentation is needed.

In the anterior or full face examination, any broadening of the nasal bridge or the alar base should be evaluated. The alar width should fall on a vertical line from the inner canthi. In trauma cases, it is important to be sure the injury did not extend into the nasoethmoid complex, as this can produce a traumatic telecanthus. The normal width in a Caucasian adult is about 34 mm.

Any pseudoelevation of the tip, caused by a saddle deformity, should be distinguished from a true traumatic elevation caused by upward displacement of the nasal spine (which is rare).

Nasal Skin Scars

Any lacerations or abrasions should be carefully noted, because they must not be confused with planned surgical incisions (e.g., for an open rhinoplasty). If any scars by chance are in the correct position they should be used. Any scarred areas may represent a potential weakness and could reopen at secondary surgery, especially early after trauma. There may also be an opportunity to revise any scar.

Internal Examination

The internal examination is probably the most important part of the examination. For it to be useful, one needs a good head light and a speculum of appropriate length to examine the whole nose or a fiberoptic endoscope. The clinical examination should first test function (i.e., the nasal airway), ideally obtaining and documenting the ease of nasal airflow. The effect of opening the internal nasal airway by pulling the soft tissue on the lateral nose laterally and the effect of vasoconstrictors, which reduce posttraumatic edema, may help to identify and focus on the cause of any obstruction. Specifically, any collapse of the middle vault should be noted.

Observation of the internal nose aims to identify:

- •

Deviated septum

- •

Resolving septal hematomas

- •

Mucosal hyperemia and/or edema

- •

Inferior turbinate hyperplasia

- •

Displacement of lateral nasal bones

- •

Evidence of nasal valve trauma

Septal hematomas are common with nasal trauma, because the nose is distorted on impact and the palatal shelf is a solid, fixed point. In children, a missed septal hematoma leads to a late delayed deviation and impaired symmetry of growth in addition to the distortion caused by the organizing hematoma.

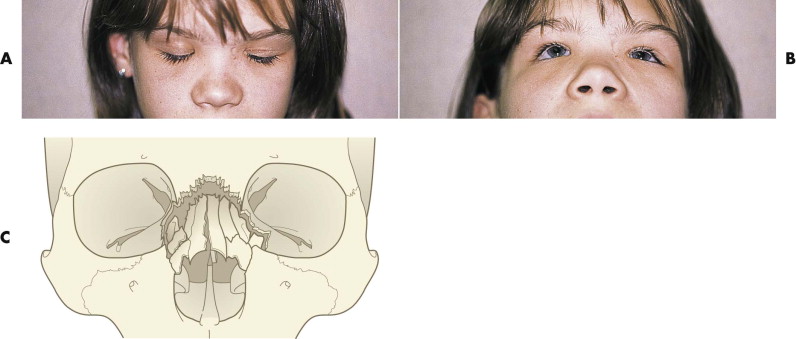

Septal fracture and dislocation may accompany hematomas. Initially, the dorsum may be merely deflected to one side, but with increased force comes a more retro-displacement of both cartilage and bone ( Fig. 26-2 ). The septum is central to correcting the symmetry and prominence of the nasal bridge. Guyuron et al. described six typical variations of septal position observed in more than 1000 revision procedures ; 40% had a simple tilt of the septum, which probably indicates no fracture. Other common presentations included a C -shaped deformity, either horizontally or vertically, and an S -shaped deformity, usually horizontally. These more extensive deformities reflect severe distortion with likely fracture or partial fracturing of the septum. It is the healing of these fractures that generates tensions leading to late deformation of the septum, which is reflected in a distorted nose.

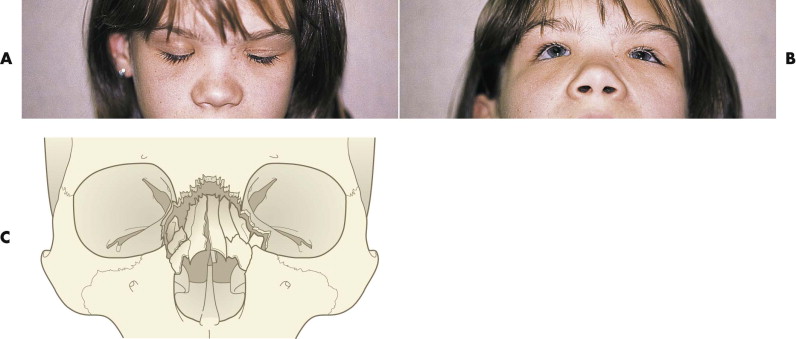

Initial fracture of the nasal bones may extend to involve the nasal process of the frontal bone, the nasal process of the maxilla, the lacrimal bone, and the lamina papyracea. With larger blunt forces that occur directly over the bridge of the nose or from an inferior direction, naso-orbitoethmoid (NOE) fractures occur with telecanthus. This results in a flat, wide nasal dorsum with decreased nasal length, decreased nasal projection and support, and columellar retraction ( Fig. 26-3 ). NOE fractures are frequently part of more extended midfacial fractures. An understanding of these common fracture patterns aids in the assessment of the secondarily deformed nose, but the need for a thorough preoperative evaluation is not obviated.

In contrast to cases of primary esthetic rhinoplasty, those involving a deformed traumatized nose more often are associated with some degree of nasal obstruction, reflecting damage to the septum or, less commonly, damage to the intranasal valve. This is more commonly seen in cases involving lacerations or penetrating injuries. Its correction requires identification of both fixed and dynamic components of the obstruction. A thorough examination of the nasal passages must be performed before and after the topical application of a vasoconstrictive agent. The shrinkage of the mucosa aids in identifying surgically reversible causes of nasal obstruction. With a nasal speculum, the position of the septum, size of the turbinates, and internal and external valves should be assessed. The fractured septum is often displaced off the maxillary crest to one side or telescoped on itself. Nasal valve obstruction is frequently found with either upper lateral cartilage displacement medially or collapse. This may be confirmed by performing the Cottle maneuver, which should improve with lateral displacement of the cheek on the obstructed side. Enlarged turbinates, especially with lateral wall displacement medially, can also contribute to further nasal obstruction.

Clinical Examination

With experience and careful examination, it is possible to evaluate the external deformity and understand the underlying structural deformity. However, it is important to have a logical approach to the clinical examination of the nose. The variables are

- •

symmetry

- •

depression of the nasal dorsum

- •

tip deformity

- •

nasal skin scars

- •

condition of the internal septal and inferior turbinate

Symmetry

Asymmetry of the face is very common, and examination of the nose for asymmetry must be undertaken in context with the whole face. Pre-injury photographs are important to exclude long-standing asymmetry. Nasal symmetry is best assessed by looking from above the patient, with the head tilted back. This allows the nasal form to be examined afresh, with the eyebrows and chin point as reference points. Once these key landmarks have been evaluated, the cupid’s bow of the upper lip can be brought into the visual field by further tilting and related to the nasal tip. In many cases, the symmetry varies along the length of the nose, and this should be noted. Deviation of the upper third of the nose most likely reflects nasal bone deformation, deviation in the lower two thirds reflects the symmetry of the septum. This should give a clear understanding about the extent and position of any asymmetry. The columella should be examined from below to confirm any tip deviation and symmetry of the nares and domes. Finally, the nasal spine should be palpated. Traumatic displacement of the nasal spine can make true central alignment of the nose impossible.

Depression Of The Nasal Dorsum

To appreciate the position of the nasal bridge or dorsum, both lateral and anterior views must be evaluated. Laterally, the nose should come off the nasion and frontal bone at an angle of about 135 degrees. This line should continue until the slight rise at the nasal tip, to give the characteristic tip break. The columella should make an angle with the upper lip of 90 to 110 degrees. From these normal values, an appreciation of the defect should be possible, allowing appropriate planning, such as how much nasal augmentation is needed.

In the anterior or full face examination, any broadening of the nasal bridge or the alar base should be evaluated. The alar width should fall on a vertical line from the inner canthi. In trauma cases, it is important to be sure the injury did not extend into the nasoethmoid complex, as this can produce a traumatic telecanthus. The normal width in a Caucasian adult is about 34 mm.

Any pseudoelevation of the tip, caused by a saddle deformity, should be distinguished from a true traumatic elevation caused by upward displacement of the nasal spine (which is rare).

Nasal Skin Scars

Any lacerations or abrasions should be carefully noted, because they must not be confused with planned surgical incisions (e.g., for an open rhinoplasty). If any scars by chance are in the correct position they should be used. Any scarred areas may represent a potential weakness and could reopen at secondary surgery, especially early after trauma. There may also be an opportunity to revise any scar.

Internal Examination

The internal examination is probably the most important part of the examination. For it to be useful, one needs a good head light and a speculum of appropriate length to examine the whole nose or a fiberoptic endoscope. The clinical examination should first test function (i.e., the nasal airway), ideally obtaining and documenting the ease of nasal airflow. The effect of opening the internal nasal airway by pulling the soft tissue on the lateral nose laterally and the effect of vasoconstrictors, which reduce posttraumatic edema, may help to identify and focus on the cause of any obstruction. Specifically, any collapse of the middle vault should be noted.

Observation of the internal nose aims to identify:

- •

Deviated septum

- •

Resolving septal hematomas

- •

Mucosal hyperemia and/or edema

- •

Inferior turbinate hyperplasia

- •

Displacement of lateral nasal bones

- •

Evidence of nasal valve trauma

Septal hematomas are common with nasal trauma, because the nose is distorted on impact and the palatal shelf is a solid, fixed point. In children, a missed septal hematoma leads to a late delayed deviation and impaired symmetry of growth in addition to the distortion caused by the organizing hematoma.

Septal fracture and dislocation may accompany hematomas. Initially, the dorsum may be merely deflected to one side, but with increased force comes a more retro-displacement of both cartilage and bone ( Fig. 26-2 ). The septum is central to correcting the symmetry and prominence of the nasal bridge. Guyuron et al. described six typical variations of septal position observed in more than 1000 revision procedures ; 40% had a simple tilt of the septum, which probably indicates no fracture. Other common presentations included a C -shaped deformity, either horizontally or vertically, and an S -shaped deformity, usually horizontally. These more extensive deformities reflect severe distortion with likely fracture or partial fracturing of the septum. It is the healing of these fractures that generates tensions leading to late deformation of the septum, which is reflected in a distorted nose.

Initial fracture of the nasal bones may extend to involve the nasal process of the frontal bone, the nasal process of the maxilla, the lacrimal bone, and the lamina papyracea. With larger blunt forces that occur directly over the bridge of the nose or from an inferior direction, naso-orbitoethmoid (NOE) fractures occur with telecanthus. This results in a flat, wide nasal dorsum with decreased nasal length, decreased nasal projection and support, and columellar retraction ( Fig. 26-3 ). NOE fractures are frequently part of more extended midfacial fractures. An understanding of these common fracture patterns aids in the assessment of the secondarily deformed nose, but the need for a thorough preoperative evaluation is not obviated.

In contrast to cases of primary esthetic rhinoplasty, those involving a deformed traumatized nose more often are associated with some degree of nasal obstruction, reflecting damage to the septum or, less commonly, damage to the intranasal valve. This is more commonly seen in cases involving lacerations or penetrating injuries. Its correction requires identification of both fixed and dynamic components of the obstruction. A thorough examination of the nasal passages must be performed before and after the topical application of a vasoconstrictive agent. The shrinkage of the mucosa aids in identifying surgically reversible causes of nasal obstruction. With a nasal speculum, the position of the septum, size of the turbinates, and internal and external valves should be assessed. The fractured septum is often displaced off the maxillary crest to one side or telescoped on itself. Nasal valve obstruction is frequently found with either upper lateral cartilage displacement medially or collapse. This may be confirmed by performing the Cottle maneuver, which should improve with lateral displacement of the cheek on the obstructed side. Enlarged turbinates, especially with lateral wall displacement medially, can also contribute to further nasal obstruction.

Esthetics

A trauma patient seeking revision is no different from a patient seeking a cosmetic rhinoplasty. Clearly, some trauma patients fit into the “warrior class” and have little regard for appearance or social behavior, but they are unlikely to seek revision surgery. Some patients who have been injured in a domestic dispute may be more demanding than a patient seeking a cosmetic rhinoplasty, because their deformity carries much more emotional impact, such as anger associated with the injury.

As with any cosmetic aspect, the patient’s wishes not only guide the surgical process but can inform the surgeon about the patient’s psychological makeup (see Chapter 30 ). Trauma patients are just as likely to be dysmorphic as any other group. The two important warning signs are vague, nonspecific comments about appearance and concerns about appearance that seem inappropriate to the clinical findings.

It is also important to determine just how the nose looked before the injury and exactly how the fractured nose compares. Old pictures may be beneficial in determining which deformities have always been present and which are secondary to the nasal trauma.

Investigations

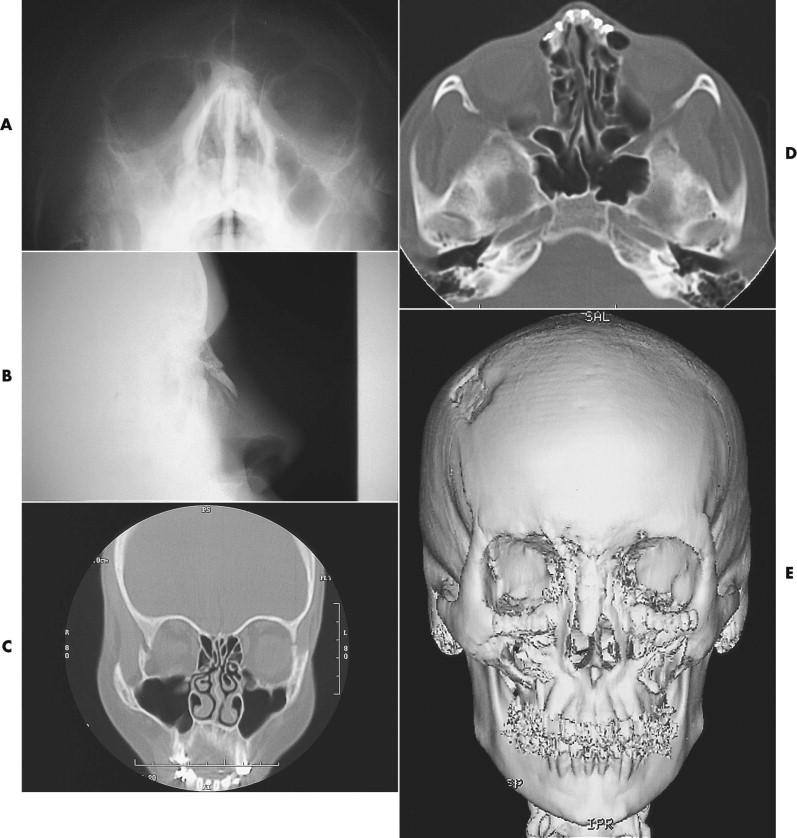

After a history and thorough examination, radiographic assessment is often helpful to exclude other facial fractures and to aid in planning any bony surgery. However, plain radiographs are even less useful than they are in primary nasal fracture repair ( Fig. 26-4A,B ). They simply do not provide an anatomic assessment of the internal nasal airway, which is often the ambiguous issue. Computed tomographic (CT) scans are the most helpful in this regard, and their axial and coronal slices provide the most complete view of the internal nasal airway (see Fig. 26-4C,D ). They are not particularly helpful for evaluation of external nasal morphology.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses