Depending on the disease progression, chronic obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) can be a severely debilitating disorder. People of all ages can be affected, but middle-age adult men who are moderately to severely overweight have the highest prevalence of OSA. Women can be affected, but to a lesser degree. Recently, OSA is being increasingly seen in the pediatric and adolescent populations. Some of these patients may be unaware of the condition and may not see their primary care physician routinely.

With expertise in facial growth and development as well as craniofacial and dentofacial anomalies, orthodontic professionals should be equipped to provide treatment for OSA patients. Several treatment modalities exist to improve a patient’s sleep pattern. Successful treatment will improve a patient’s subjective as well as objective assessment of their daytime alertness.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION

Adult orthodontics has become more common in recent years, and thus OSA patients are more likely to present at the orthodontic office for examination and consultation. The classic presenting symptom of OSA is excessive daytime sleepiness. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a simple, inexpensive screening tool. Patients are asked a series of questions to assess their relative “sleep health.” However, this test does not distinguish between OSA and the many other types of sleep-disordered breathing (e.g., restless legs syndrome).

Accurate diagnosis of OSA requires an overnight polysomnographic examination. Independent sleep clinics and full-service hospitals with sleep clinics can perform the test. Polysomnography combines multiple tests, including electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), electro-oculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), respiratory rate, tidal volume, inspiratory/expiratory volume, as well as the number and severity of apneas and hypopneas. An apnea is defined as any cessation in breathing for 10 seconds or more with an arterial oxygen desaturation of 2% to 4%. A hypopnea is defined as a 50% decrease in airflow for 10 seconds or more with a concomitant drop in arterial oxygen saturation. The exact magnitude of desaturation for a hypopnea varies in the literature. Central apnea must also be differentiated from obstructive apnea. Patients with obstructive apnea typically display respiratory effort without being able to ventilate adequately. Patients with central apnea exhibit decreased respiratory effort. The distinction between central and obstructive apnea is essential in determining the most appropriate treatment for the individual patient; certain treatments are effective only for obstructive apnea.

Polysomnography typically provides a patient score reflecting the number of apneas and hypopneas, called the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI). This may also be reported as the respiratory disturbance index (RDI). The AHI and RDI are slightly different but essentially interchangeable. Patients in normal sleep have an RDI of 5 or less. Patients with mild sleep apnea have an RDI of 5 to 15, with moderate sleep apnea typically 15 to 30 events and severe apnea 30 or more events per hour. To illustrate the clinical significance of this scale, a patient with an RDI of 60 stops breathing or has a significant oxygen desaturation for at least 10 seconds every minute. Depending on the length of the apnea/hypopnea, significant reduction in oxygen perfusion to the brain can occur, causing increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and other cardiac conditions.

The criteria used to determine successful treatment of OSA varies widely. For most successful outcomes, clinicians strive to achieve at least a 50% reduction in the RDI, or an RDI of less than 20. More stringent criteria for success involve achieving a posttreatment RDI of less than 10. A recent report states that successfully treated patients have no increased morbidity or mortality. Untreated individuals have 37% greater 5-year morbidity and mortality. These statistics result from the higher incidence of motor vehicle accidents, heart attack, stroke, arrhythmia, and hypertension. One study concluded that the incidence of motor vehicle crashes in OSA patients can be compared with driving while intoxicated, which presents a major public health risk.

NONDENTAL OR NONORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

Once a patient is diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, the most appropriate treatment is determined. Because many OSA patients are overweight, one treatment option includes weight loss. Reports vary, but some investigations have shown that significant weight loss can reduce a person’s RDI as much as 50%. In patients who are obese (>120% of ideal body weight, or body mass index [BMI] >30) or morbidly obese (>200% of ideal weight, or BMI >40), the weight loss can also help improve overall health status. Overweight patients who lose significant amounts of weight can greatly reduce or eliminate such problems as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, orthopedic conditions, and cardiac/stroke risks.

Other habits that can reduce the symptoms and severity of the sleep apnea include stopping alcohol consumption 3 hours before sleep. Alcohol acts as a respiratory depressant. Studies show that mild or borderline OSA can become frank obstructive sleep apnea after the patient is challenged with 3 ounces of 80 proof alcohol. Both the duration and the depth of sleep are greatly reduced, as is the amount of time in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Sleep position also can dramatically affect the amount and quality of sleep. Patients sleeping in the supine position will notice that the laxity in the soft tissues combined with gravity often increases the number and severity of apneas and hypopneas. Positional aids to assist the patient in maintaining a lateral decubitus position for sleep can significantly improve the RDI.

Continuous Positive Air Pressure

A common treatment modality for OSA is continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) ( Fig. 20-1 ).

Whether the patient is diagnosed with obstructive or central apnea, CPAP can successfully reduce the symptoms. In addition, CPAP can effectively treat the mildest cases to the most severe cases of sleep apnea. CPAP works by forcing air into the nasopharynx and oropharynx to maintain airway patency.

After diagnosis, the clinician provides a prescription for a CPAP machine. To test the efficacy and to titrate to the proper settings, a second polysomnography is performed, or the second half of the diagnostic polysomnography is conducted with CPAP in place. The mask is fitted to the patient, and the patient is allowed to return to sleep. Once the apneas and hypopneas begin, the airflow and air pressure can be adjusted to bring the RDI into the normal range. The goal is to have the patient at the lowest possible flow rate and pressure that will ensure a patent airway. This allows an increase in the settings should the patient’s airway accommodate over time and begin to collapse again.

NONDENTAL OR NONORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

Once a patient is diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, the most appropriate treatment is determined. Because many OSA patients are overweight, one treatment option includes weight loss. Reports vary, but some investigations have shown that significant weight loss can reduce a person’s RDI as much as 50%. In patients who are obese (>120% of ideal body weight, or body mass index [BMI] >30) or morbidly obese (>200% of ideal weight, or BMI >40), the weight loss can also help improve overall health status. Overweight patients who lose significant amounts of weight can greatly reduce or eliminate such problems as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, orthopedic conditions, and cardiac/stroke risks.

Other habits that can reduce the symptoms and severity of the sleep apnea include stopping alcohol consumption 3 hours before sleep. Alcohol acts as a respiratory depressant. Studies show that mild or borderline OSA can become frank obstructive sleep apnea after the patient is challenged with 3 ounces of 80 proof alcohol. Both the duration and the depth of sleep are greatly reduced, as is the amount of time in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Sleep position also can dramatically affect the amount and quality of sleep. Patients sleeping in the supine position will notice that the laxity in the soft tissues combined with gravity often increases the number and severity of apneas and hypopneas. Positional aids to assist the patient in maintaining a lateral decubitus position for sleep can significantly improve the RDI.

Continuous Positive Air Pressure

A common treatment modality for OSA is continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) ( Fig. 20-1 ).

Whether the patient is diagnosed with obstructive or central apnea, CPAP can successfully reduce the symptoms. In addition, CPAP can effectively treat the mildest cases to the most severe cases of sleep apnea. CPAP works by forcing air into the nasopharynx and oropharynx to maintain airway patency.

After diagnosis, the clinician provides a prescription for a CPAP machine. To test the efficacy and to titrate to the proper settings, a second polysomnography is performed, or the second half of the diagnostic polysomnography is conducted with CPAP in place. The mask is fitted to the patient, and the patient is allowed to return to sleep. Once the apneas and hypopneas begin, the airflow and air pressure can be adjusted to bring the RDI into the normal range. The goal is to have the patient at the lowest possible flow rate and pressure that will ensure a patent airway. This allows an increase in the settings should the patient’s airway accommodate over time and begin to collapse again.

ORTHODONTIC AND DENTAL TREATMENT

Oral appliances have repeatedly been shown to be an effective form of treatment for mild to moderate OSA. If a patient with severe sleep apnea (RDI >30) cannot tolerate CPAP and is not a surgical candidate or refuses surgical correction, a dental appliance can be the most acceptable form of treatment. In fact, recent studies from the Cochrane Collaboration have shown higher efficacy with oral appliances than with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty or other forms of soft tissue surgery.

Oral Appliances

Multiple appliance designs exist, both custom and stock. Before selecting a particular dental appliance, the patient must undergo the same polysomnography to determine the type, severity, and location of the obstruction. If the site is the upper airway (nasal cavity or retropalatal area), efficacy of mandibular protrusion appliances and tongue-retaining devices may be limited. In patients with hypertrophic tonsils and adenoids as well as a tongue obstruction, the efficacy of the dental appliance may be improved by tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy.

Tongue-positioning appliances

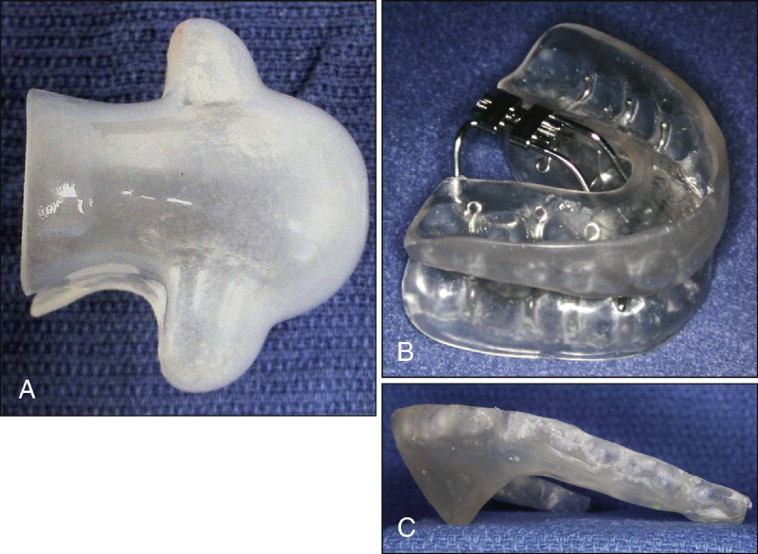

In the supine position, all gravity-dependent tissues, including the tongue, will tend to fall posteriorly unless otherwise supported. The tongue base is held anteriorly by the genial tubercles. If this support is insufficient, a tongue-retaining device can be used. To fit a tongue appliance, a piece of dental floss is gently wrapped around the tongue, removed, and measured ( Fig. 20-2, A ).

The appliance comes in three sizes: small, medium, and large. If the tongue is between two sizes, the manufacturer recommends using the larger of the two sizes. This appliance also comes in two styles: an intraoral appliance for patients with a full dentition and an extraoral design for patients with multiple missing teeth. The bulb of the appliance is moistened and compressed, and the tongue is inserted into the bulb. Both suction and the adhesion from the thin film of saliva on the plastic maintain the tongue in a more forward position, opening the oropharyngeal airway. This class of appliance is used infrequently because most patients find it uncomfortable and choose not to use it long term.

In rare cases the tongue can be surgically tethered to the genial tubercles, creating ankyloglossia (“tongue-tie”). Because of the associated speech defects, this is not usually performed.

Mandibular positioning appliances

A second class of appliances is available to protrude the mandible and assist in maintaining this forward position during sleep ( Fig. 20-2, B ). The appliances are removable, allowing the patient to use the appliance each night. Because it is smaller than a CPAP machine, the appliance is more mobile and can be taken on trips. The specific protrusion appliance can be individually selected for the patient using multiple factors, including cost, convenience, durability, adjustability, and patient comfort. Because anterior repositioning appliances function similarly, the patient and clinician can choose the most appropriate and comfortable appliance. Compliance is essential; for just as with CPAP, if the appliance is not worn, no improvement is observed.

Almeida, Lowe, et al. studied potential side effects or changes to the bite resulting from long-term use of a dental sleep appliance. They observed tremendous variation, from minimal dental movement to both dental and apparent skeletal movement of the mandible. Many patients with more marked dental and skeletal changes had positive occlusal change with improvement of a Class II malocclusion. In some patients a Class I relationship was obtained. Some Class I patients became mildly Class III. Because the appliance’s primary function was to cure the sleep apnea, occlusal changes usually were not treated. It is unclear whether occlusal changes would persist if appliance use were discontinued.

To fabricate these appliances, typically, upper and lower dental impressions are obtained. Range of motion is measured, including maximum opening, left and right lateral excursion, and maximum protrusion. The appliance is constructed using a position approximately one half to two thirds the patient’s maximum protrusion and several millimeters open. Custom bite registrations in centric occlusion and the construction position are obtained. A George gauge can be helpful in stabilizing the patient in the construction bite position. The impressions and bite registrations can then be sent to a commercial laboratory for appliance fabrication, or an appliance may be made on site. In-house appliances may be fabricated and delivered more quickly and are more cost-effective for the patient. After delivery, the patient returns for assessment of appliance fit, comfort, and potential changes in the bite.

A positive-pressure thermoforming machine (e.g., BioStar, Great Lakes Orthodontics, Tonawanda, N.Y.) can be used to make a relatively inexpensive but effective mandibular positioning appliance ( Fig. 20-2, C ). A 2-mm-thick piece of thermoforming splint material can be formed over the maxillary model. Cold-cure acrylic can then be added to make a flange that extends inferiorly and palatally to rest gently against the lingual mucosa of the mandible in the protruded position. The flange can be altered by adding or removing the acrylic to advance or retract the mandible for patient comfort and additional symptom relief. A dental appliance also has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive and entirely reversible. If the patient does not obtain the desired and necessary improvement, no permanent changes have occurred, and alternative treatment options can be explored.

To measure the effect of the appliance, a lateral cephalometric radiograph taken in centric occlusion provides a baseline position for assessing later bite changes and determining the amount of airway opening. After appliance delivery and confirming patient comfort, a second radiograph can be taken to assess the two-dimensional change in the airway. Recent advances in three-dimensional imaging with cone-beam computed tomography may prove useful in the future to examine these airway changes with greater detail and accuracy.

Finally, it is important to obtain a follow-up sleep study with the appliance in place to objectively document the level of improvement. Some patients will report significant subjective change with the appliance, which may or may not be substantiated by the sleep test. If objective improvement is not observed, the patient should be provided alternate treatment options to improve the sleep apnea in measurable terms.

Surgical Orthodontic Options

Although dental appliances often work well in the patient with mild to moderate OSA, these devices are not universally effective and may not be appropriate in more severe cases. For patients with severe sleep apnea who do not want long-term CPAP, surgery is a viable treatment alternative. Surgery may be confined to the site of obstruction, such as with a uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), or used as an aid in weight loss, such as bariatric surgery. Recent studies report only 40% long-term success with UPPP, however, and thus alternate forms of surgical intervention are being explored.

Genioplasty

An alternate first-tier surgical therapy for OSA is an advancement genioplasty. The best candidates have a functional occlusion with good maxillomandibular skeletal positioning, but have deficient chin projection called retrogenia or microgenia. Retrogenia must be differentiated from retrognathia. With retrognathia the mandible is small and in a poor sagittal position, but the bony chin button may be adequate.

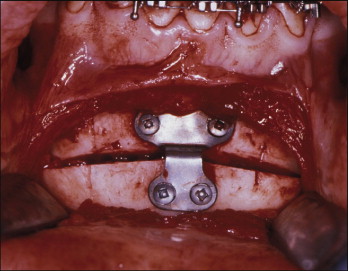

In some patients a standard genioplasty is performed, taking care to have the genial tubercles in the segment that is advanced ( Fig. 20-3 ). Other osteotomy designs include advancing a full-thickness area of the mandibular symphysis containing the genial tubercles. Once the lingual cortex of the core of bone is buccal to the buccal cortex of the mandibular body, the core is rotated 90 degrees to maintain the advanced position.

Multiple minor variations in osteotomy design exist, based on anatomical restrictions and surgeon preference. If only partial resolution of the symptoms results from genioplasty alone, a second surgical phase of treatment that advances both the maxilla and the mandible can be performed.

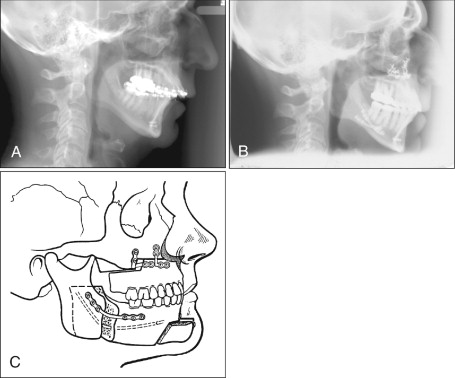

Maxillomandibular advancement

Some OSA patients will elect to pursue maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) quickly because they want their symptoms resolved as soon as possible ( Fig. 20-4 ). Because this does not allow presurgical orthodontic treatment, the published risks associated with MMA include postoperative malocclusion. The preferred approach should address the pretreatment malocclusion using presurgical orthodontic therapy to prepare the dental arches. CPAP or alternative forms of OSA treatment can be used to address the excessive daytime somnolence and the negative effects of OSA during this presurgical orthodontic phase. Once the dental arches complement each other, both an improved airway and an improved occlusion can be obtained concurrently.

Once MMA is complete and symptoms have resolved, CPAP can be discontinued. Interestingly, patients undergoing orthognathic surgery often lose 10 or more pounds, which can be an additional source of health improvement and symptom resolution if maintained.

As with all surgical orthodontic patients, presurgical orthodontic therapy for MMA should focus on all three planes of space. The transverse, sagittal, and vertical relationship of the teeth and jaws should be assessed. The treatment plan must include where the teeth will be positioned in each jaw and where each jaw will be positioned relative to the cranial base. Special consideration is given to arch width, arch form, leveling, and arch length deficiency. Each aspect is addressed separately here for ease of discussion but must be considered in a combined and coordinated manner.

Transverse dimension and arch form.

The interarch transverse relationship is especially important in MMA. Without adequate attention to this dimension, the final position of the mandible relative to the maxilla may be adversely affected. To maximize improvement, when diagnostic models are taken, the orthodontist and oral surgeon should assess the transverse dimension in two positions: the current bite position and the anticipated final bite position. This is particularly important in significant Class II or Class III malocclusions. For example, a Class II patient may not have a frank crossbite in the presenting bite; however, as the mandible is advanced to Class I, either an edge-to-edge transverse relationship or a true crossbite may be observed. If undiagnosed, either the patient will have a crossbite postsurgically, or the mandible will not be advanced to Class I. Both leave the patient with a malocclusion. Conversely, Class III patients may demonstrate a crossbite during the initial examination, but when the maxilla is advanced relative to the mandible to Class I as part of the MMA, the patient may now have too much buccal overjet.

Although maxillary transverse excess can be easily managed by a .036-inch heat-treated stainless steel lingual arch to constrict the arch, the situation must be carefully evaluated before decreasing arch dimension in the OSA patient. Smaller arches leave less room for the tongue, which may exacerbate the sleep apnea. The planned orthodontic constriction might decrease the effectiveness of the MMA. This relationship is unclear at present, but a general rule with OSA should be to make more space, not less. Instead of constricting the maxilla, the clinician should consider increasing the dimension of the mandibular basal bone through transverse mandibular symphyseal distraction osteogenesis, as discussed later.

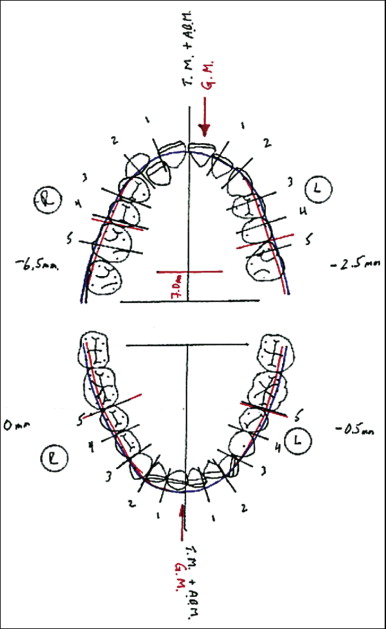

A useful tool to assist in the diagnosis of transverse problems is the occlusogram allows the practitioner to perform a treatment simulation on an acetate film ( Fig. 20-5 ). To construct this, all the teeth are traced on acetate. Orientation marks are made to establish the current anteroposterior (AP) position of the mandible to the maxilla. The ideal mandibular arch template is established first. AP changes in the mandible (relative to the maxilla) are performed by sliding the acetate forward to simulate a mandibular advancement or by sliding the mandibular acetate posteriorly to simulate a maxillary advancement. Now the ideal mandibular arch dimensions are transferred to the maxillary arch to establish the ideal maxillary arch size and arch form. Recent advances in modeling systems can allow this simulation to now be performed electronically.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses