T he new and popular trends in orthodontics, as advocated by orthodontic companies, appliance inventors, and self-proclaimed experts, seem to have reduced clinical orthodontics to the use of self-ligating brackets, high-tech archwires with no need for wire bending, and permanent retention with bonded retainers.

Several influential lecturers on the international circuit demonstrate a purely mechanistic approach to orthodontic treatment and largely disregard the aspects of diagnosis, treatment planning, and treatment objectives. Even in cases with marked crowding, proclined lower incisors, or the six mandibular anterior teeth well above the functional occlusal plane, these “experts” bond orthodontic attachments to all teeth and take a nonextraction treatment approach. Superelastic, round or rectangular archwires without bends are used to level and align the dental arches. By necessity, this leads to lateral expansion of the mandibular canines and premolars and further lower incisor proclination, as evidenced by the cephalometric films and tracings of these individuals. After debonding, the recommendation is that teeth be permanently retained with fixed retainers bonded from first premolar to first premolar.

The purpose of this chapter is to emphasize the long-term follow-up clinical research and experience-based information on proper orthodontic treatment that benefits the patients and ensures optimal treatment and stable results. It addresses the following needs:

- •

For evidence-based treatment planning

- •

For archwire bending

- •

To intrude mandibular rather than maxillary incisors

- •

To use transpalatal arches as supplements to labial archwires

- •

For differentiated long-term rather than permanent retention

NEED FOR EVIDENCE-BASED TREATMENT PLANNING

Teeth are positioned exactly in the oral cavity for a reason. Even in a malocclusion, there is equilibrium between forces from the inside and from the outside of the dentition. If the orthodontist’s purpose is to change tooth positions significantly, the clinical problem is to estimate the amount of change that will remain stable over time.

Malocclusion of the teeth is caused by an interplay between inborn genetic factors and external environmental factors. Edward Angle believed that the environment could be modified by orthodontic treatment, that orthodontic treatment regenerated new bone, and that it would be possible to produce stable ideal occlusions without tooth extractions. However, we know now that bone yields to functional forces, and that premolar extractions are required in some cases. The percentage of extraction cases reflects a judgment as to the importance of how much the equilibrium of environmental forces around the dentition can be modified permanently. There is ample evidence in the literature that expansion in the lower arch, particularly in the canine region, is unstable, with little or no evidence to the contrary. Transverse expansion across the canines is almost never maintained, probably because of lip pressures at the corners of the mouth. It is important, therefore, to avoid an increase in the normal mandibular intercanine width (25-26 mm) during orthodontic treatment. Some excellent clinical long-term studies have demonstrated that not only the mandibular intercanine distance, but also the patient’s pretreatment mandibular arch form, should constitute a guide to arch shape.

The lower incisor position in space is also controlled by a balance of muscle forces, which may lie within a narrow zone of stability. Moving lower incisors forward more than 2 mm is problematic for stability, probably because lip pressure seems to increase sharply at that point. Further research is needed before evidence-based clinical guidelines on lower incisor proclinations can be established.

NEED FOR ARCHWIRE BENDING

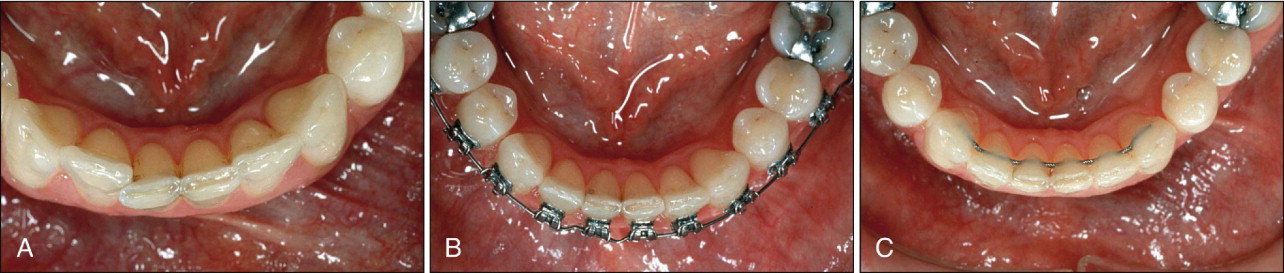

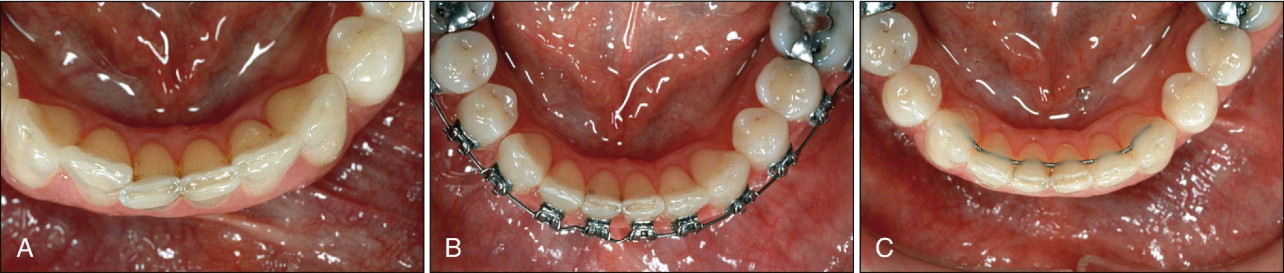

Individualized archwire bends should be used to secure early and full correction of all rotations in the original malocclusion. The main reason is that even slightly broken contacts ( Fig. 8-1, A ) in both untreated cases and treated cases are the predictable starting points for relapse and later increased crowding.

Slight undercorrection of previously rotated teeth is not easy to detect clinically. The size of the archwire bends necessary to produce full-rotation correction is often remarkably large ( Fig. 8-1, B ). This results from the slack between the archwire slot and the wire. Fine details must be checked toward the end of treatment by careful comparison with the pretreatment plaster models. In the maxilla, a mouth mirror is necessary to check the incisor region. If these steps are not taken, an undercorrected case may look good or even excellent on clinical examination in the orthodontist’s chair.

Small, meticulous archwire bends will also help ensure that the distal contact areas of the mandibular lateral incisors are placed slightly labial to the mesial contact points of the mandibular canines, and that the teeth are retained in these positions ( Fig. 8-1, C ). This is particularly important when the distal aspects of one or both lateral incisors are lingually displaced at the start of treatment. The mandibular anterior region is the most common area for increased crowding and relapse after treatment. Moderate crowding can be masked if the four incisors are positioned as a block outside the mesial contacts of the mandibular canines.

Careful archwire bends are also necessary to provide the desired and symmetrical axial inclinations (crown torque) of the maxillary and mandibular canines and premolars before appliance removal, to provide a full and radiant smile ( Fig. 8-2 ). No straight-wire approach or “fully programmed preadjusted appliance” used by an orthodontist without wire bending can place every tooth in correct position in all three planes of space.

NEED FOR ARCHWIRE BENDING

Individualized archwire bends should be used to secure early and full correction of all rotations in the original malocclusion. The main reason is that even slightly broken contacts ( Fig. 8-1, A ) in both untreated cases and treated cases are the predictable starting points for relapse and later increased crowding.

Slight undercorrection of previously rotated teeth is not easy to detect clinically. The size of the archwire bends necessary to produce full-rotation correction is often remarkably large ( Fig. 8-1, B ). This results from the slack between the archwire slot and the wire. Fine details must be checked toward the end of treatment by careful comparison with the pretreatment plaster models. In the maxilla, a mouth mirror is necessary to check the incisor region. If these steps are not taken, an undercorrected case may look good or even excellent on clinical examination in the orthodontist’s chair.

Small, meticulous archwire bends will also help ensure that the distal contact areas of the mandibular lateral incisors are placed slightly labial to the mesial contact points of the mandibular canines, and that the teeth are retained in these positions ( Fig. 8-1, C ). This is particularly important when the distal aspects of one or both lateral incisors are lingually displaced at the start of treatment. The mandibular anterior region is the most common area for increased crowding and relapse after treatment. Moderate crowding can be masked if the four incisors are positioned as a block outside the mesial contacts of the mandibular canines.

Careful archwire bends are also necessary to provide the desired and symmetrical axial inclinations (crown torque) of the maxillary and mandibular canines and premolars before appliance removal, to provide a full and radiant smile ( Fig. 8-2 ). No straight-wire approach or “fully programmed preadjusted appliance” used by an orthodontist without wire bending can place every tooth in correct position in all three planes of space.

NEED TO INTRUDE MANDIBULAR RATHER THAN MAXILLARY INCISORS

Analogous with recent concepts of treatment planning in general and esthetic dentistry, the mechanical intrusion of maxillary incisors in orthodontics should be made with the utmost care to avoid “hiding” these teeth behind the upper lip. In most deep-bite cases, intrusion of the mandibular teeth should be done.

Maxillary Intrusion Arch Versus Bite Plate

Lindauer, Lewis, and Shroff recently made a comparative clinical and cephalometric analysis of the effects of two common procedures to reduce deep overbite in 40 patients: maxillary incisor intrusion using an intrusion arch and posterior tooth eruption using an anterior bite plate. Both the intrusion arches and the bite plates were successful in correcting the deep overbite over a relatively short period of treatment, although by different mechanisms. The maxillary incisors in the intrusion group were significantly intruded during treatment, with a corresponding decrease in the lip–upper incisor measurement, from a mean of 5.4 mm (SD 2.0 mm) to 3.0 mm (SD 1.4 mm), as measured in relaxed-lip posture. The overbite correction in the bite plate group was achieved by a combination of lower incisor intrusion, significant flaring of the lower incisors, and a small opening rotation of the mandibular plane secondary to posterior tooth eruption. The clinical lip–upper incisor measurement was reduced by about 1 mm in the bite plate group.

The significant decrease of about 2.5 mm of maxillary incisor display with the lips at rest when using a maxillary intrusion arch should be an alarming finding when patients with deep overbite and minimal incisor show are treated orthodontically. Any maxillary incisor intrusion must be made with due respect to (1) the patient’s initial tooth display with relaxed lips, (2) the show of maxillary incisors with the patient speaking, and (3) the patient’s age and gender. Maxillary incisor intrusion is therefore rarely indicated in the average orthodontic patient with deep anterior overbite. Normative values for maxillary incisor display with relaxed lips, as observed during speech, are now available for all age groups.

As a general rule, it is detrimental to make orthodontic patients look older than their chronologic age. In some deep overbite cases, when patients demonstrate little upper incisor with relaxed lips for their age group at the start of treatment ( Fig. 8-3, A

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses