The world is facing an increased demand for health care and disease prevention. The consequence of this demand is increasing requests for public and private funding. To cope with this request for funds, only those needs based on sound scientific evidence should be met.

The increasing demands and rising costs require that professionals review treatment and prevention strategies to make sure that these are not the result of pressure from patients or a personal pursuit. It is imperative that endeavors undertaken by professionals increase the quality of life for specific patients and benefit the general population.

When focusing on oral health–related quality of life in relation to orthodontics, it is important to realize that for the majority of the world’s population, orthodontic treatment is not a priority; their priorities are obtaining the basic necessities of life, such as food, shelter, and clothing. Additionally, research into the demand for treatment of oral conditions often uses a self-administered questionnaire, so the patient must be able to read. Therefore the only scientific data available on this issue come from the developed world.

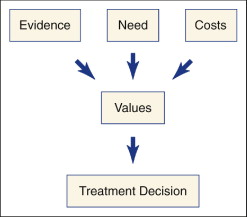

If patients with craniofacial malformations and malocclusions need orthodontic treatment, the decision to treat should be made based on consumer values. Generally, in a values-based health care system, decisions should be made using the knowledge from the outcomes of scientific evaluation of prevention programs and treatment methods. The main values to be addressed are evidence, need, and costs ( Fig. 1-1 ).

EVIDENCE-BASED ORTHODONTICS

The values of “evidence” and “costs” can ethically be seen to be directed toward two different goals: evidence-based medicine alludes to an individual’s ethics (doing everything possible for the patient), whereas cost-effectiveness alludes to social ethics (maximum gains in population health from a finite budget). In general, regarding evidence-based medicine and cost-effectiveness, the common concern is that the outcome measures used in clinical trials should be as relevant as possible to the patient and include the effects on quality of life. Measuring the quality of life should be based on consumer values if orthodontic treatment is to remain a part of publicly funded health care systems.

Regarding evidence-based orthodontic care (barring a few exceptions), new treatment methods and materials are often proposed without genuine interest in the experimental testing by orthodontic professionals or the industry. Orthodontists will often change the materials they use or the treatment methods in a clinical setting without sound scientific evidence to support the change. Although available, no consistent regulatory measures are implemented to monitor the safety, costs, and efficacy of the primary process in orthodontic care.

NEED FOR ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

The present interest in the guidelines regarding indications for orthodontic treatment is not new. Different methods for assessing the need for orthodontic treatment have been described for the last 50 years, including Handicapping Labiolingual Deviations (HLD), Treatment Priority Index (TPI), Handicapping Malocclusions, Occlusal Index (OI), and Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI). These methods are based on a comparison between irregular malocclusion and normal or ideal occlusion, as well as on the assumption that “the greater the deviation from the norm, the greater the risk for problems.” Solow correctly questions the validity of this assumption because the limiting values employed in the indices are arbitrary. For example, it would be impossible to demonstrate any difference in the risk involved in having an overjet just above or just below any specific millimeter limit.

The Swedish system is based on a gradation of various types of malocclusions into one of four categories. A child is classified in the category covering the most severe deviation. The Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN), the Need for Orthodontic Treatment Index (NOTI), and the Index of Complexity, Outcome, and Need (ICON) are based on the same principles as the Swedish system. Unfortunately, these systems cannot be used internationally. A Dutch reliability and validity study concluded that the ICON needs to be adjusted for the specific Dutch perception of need for orthodontic treatment. This probably holds true for other countries and cultures as well.

Assessment of individual treatment needs is a process that varies in different countries, depending on the structure of health care and orthodontic care. Ideally, patients, orthodontic professionals, and third parties should agree on a method for the distribution of financial resources. The amount of money that is available for orthodontic care per country should be balanced with the extent of orthodontic care required by the population.

In 1990 a Danish system was introduced based on health risks related to malocclusion. By explicitly incorporating an assessment of the health risks, this approach differs from the other screening systems. This model addresses the following health risks:

- •

Risk of damage to the teeth and surrounding tissues

- •

Risk of functional disorders

- •

Risk of psychosocial stress

- •

Risk of late sequelae

The problem with the Danish system (in a society with an increasing demand for orthodontic treatment) is that improvement in quality of life for everyone cannot be seen as a task for public financing. It leads to questions such as, “Is it legitimate to use health resources [for persons with a] risk of psychosocial stress?” and “How should body dysmorphic disorder in teenagers and adults be handled?”

In Denmark, third-party financing is provided by the community orthodontic service, and 29% of all children are treated orthodontically. In Norway, with a combination of public and private financing of orthodontic care, an estimated 35% of the children are treated. It seems that the “gatekeeper” function (practitioner involved in screening process) is not a problem in Scandinavia, although it may be in other European countries and in the United States, because often the gatekeeper is also the health care provider. This is an undesirable situation because it can promote the misuse of financial resources and overtreatment.

In The Netherlands a nationwide longitudinal epidemiological study showed that an increase in orthodontic care delivered between 1990 and 1996 did not improve the dental health of 20-year-old patients in terms of the prevalence of malocclusions, the demand for orthodontic treatment, and satisfaction with tooth position. These findings are supported by a systematic literature search initiated by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (2005). A global solution to these dilemmas has not yet been presented.

The validity of “improvement in quality of life” as an indicator for orthodontic treatment must still be substantiated, but few tools for measurement of oral health–related quality of life have been developed, especially concerning children. Proper measurements of oral health–related quality of life can be used to assess both the need for and the outcome of clinical interventions from the perspective of the individual in question or the population under study.

NEED FOR ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

The present interest in the guidelines regarding indications for orthodontic treatment is not new. Different methods for assessing the need for orthodontic treatment have been described for the last 50 years, including Handicapping Labiolingual Deviations (HLD), Treatment Priority Index (TPI), Handicapping Malocclusions, Occlusal Index (OI), and Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI). These methods are based on a comparison between irregular malocclusion and normal or ideal occlusion, as well as on the assumption that “the greater the deviation from the norm, the greater the risk for problems.” Solow correctly questions the validity of this assumption because the limiting values employed in the indices are arbitrary. For example, it would be impossible to demonstrate any difference in the risk involved in having an overjet just above or just below any specific millimeter limit.

The Swedish system is based on a gradation of various types of malocclusions into one of four categories. A child is classified in the category covering the most severe deviation. The Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN), the Need for Orthodontic Treatment Index (NOTI), and the Index of Complexity, Outcome, and Need (ICON) are based on the same principles as the Swedish system. Unfortunately, these systems cannot be used internationally. A Dutch reliability and validity study concluded that the ICON needs to be adjusted for the specific Dutch perception of need for orthodontic treatment. This probably holds true for other countries and cultures as well.

Assessment of individual treatment needs is a process that varies in different countries, depending on the structure of health care and orthodontic care. Ideally, patients, orthodontic professionals, and third parties should agree on a method for the distribution of financial resources. The amount of money that is available for orthodontic care per country should be balanced with the extent of orthodontic care required by the population.

In 1990 a Danish system was introduced based on health risks related to malocclusion. By explicitly incorporating an assessment of the health risks, this approach differs from the other screening systems. This model addresses the following health risks:

- •

Risk of damage to the teeth and surrounding tissues

- •

Risk of functional disorders

- •

Risk of psychosocial stress

- •

Risk of late sequelae

The problem with the Danish system (in a society with an increasing demand for orthodontic treatment) is that improvement in quality of life for everyone cannot be seen as a task for public financing. It leads to questions such as, “Is it legitimate to use health resources [for persons with a] risk of psychosocial stress?” and “How should body dysmorphic disorder in teenagers and adults be handled?”

In Denmark, third-party financing is provided by the community orthodontic service, and 29% of all children are treated orthodontically. In Norway, with a combination of public and private financing of orthodontic care, an estimated 35% of the children are treated. It seems that the “gatekeeper” function (practitioner involved in screening process) is not a problem in Scandinavia, although it may be in other European countries and in the United States, because often the gatekeeper is also the health care provider. This is an undesirable situation because it can promote the misuse of financial resources and overtreatment.

In The Netherlands a nationwide longitudinal epidemiological study showed that an increase in orthodontic care delivered between 1990 and 1996 did not improve the dental health of 20-year-old patients in terms of the prevalence of malocclusions, the demand for orthodontic treatment, and satisfaction with tooth position. These findings are supported by a systematic literature search initiated by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (2005). A global solution to these dilemmas has not yet been presented.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses