Chapter 7

Pulpectomy for primary teeth

James A. Coll

Diagnostic concerns

Clinical diagnosis

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD; AAPD Reference Manual, 2013–14) Guideline on Pulp Therapy states that the type of pulpal treatment depends on whether the pulp is vital or nonvital. Pulpal vitality assessment is based on reaching one of four clinical diagnostic assessments: normal pulp (i.e., a tooth with shallow caries but is symptom free and would respond normally to pulp tests); reversible pulpitis (a tooth with an inflamed pulp that is capable of healing); symptomatic or asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis (an inflamed pulp incapable of healing); or necrotic pulp. The clinical diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis and/or necrosis is a primary tooth with any one or more of the following:

- sinus tract or gingival swelling not associated with periodontal disease;

- history of spontaneous unprovoked toothache;

- excessive tooth mobility not associated with exfoliation;

- furcation/apical radiolucency;

- internal/external root resorption.

Pain evaluation

Teeth having no signs or symptoms of irreversible pulpitis or necrosis but exhibiting provoked pain of short duration relieved by brushing or analgesics or removing the stimulus are assessed as having reversible pulpitis and are capable of healing. There is evidence in primary molars (Farooq et al., 2000) that pain can last up to 20 min and still be reversible pulpitis because a child may complain while a piece of candy or food is lodged in the cavitated or interproximal lesion. According to Camp (2008), spontaneous pain is a persistent or throbbing pain that occurs without provocation or persists long after the causative factor has been removed. In a histologic study of deep carious lesions in primary teeth (Guthrie et al., 1965), it was demonstrated that a history of spontaneous toothache is associated with extensive histologic pulpal degenerative changes that can extend into the root canals. A child with a history of spontaneous pain in a primary tooth should not receive a vital pulp treatment because they are candidates for pulpectomy or extraction (Camp, 2008). A normal pulp is a symptom-free tooth with normal response to appropriate pulp tests. For primary teeth, the appropriate clinical tests are palpation, percussion, and mobility, as thermal and electric pulp tests are unreliable (Camp, 2008). The Pulp Therapy Guideline (AAPD Reference Manual, 2013–14) states that teeth diagnosed as having a “normal pulp” or “reversible pulpitis” are classified as having vital pulps and treated with vital pulp therapy. Teeth diagnosed as having “irreversible pulpitis or necrosis” are treated with extraction or pulpectomy for primary teeth.

Any planned pulpectomy treatment must include consideration of the restorability of the tooth, the patient’s medical history, whether to extract, how long is the likely exfoliation of the tooth in question, and the importance of the tooth to prevent space loss (especially second primary molars before the first permanent molar has erupted).

Interim therapeutic restorations for diagnosis

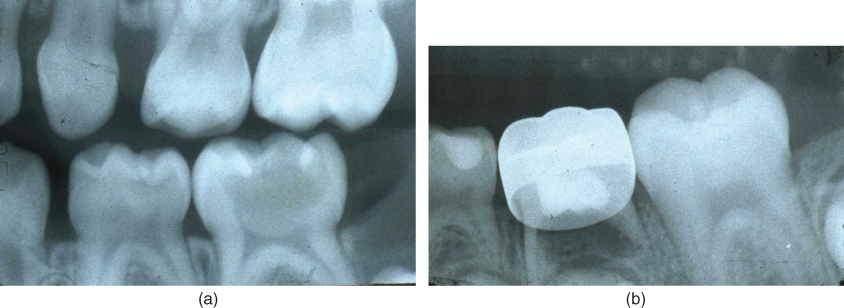

The diagnosis of the primary tooth’s vitality is not always straightforward. A primary molar with deep distal caries near the pulp without gingival swelling, but has pain of a short duration when the child chews a candy, can be easily misdiagnosed as vital. Performing vital pulp treatment with a pulpotomy on such a tooth can fail because of misdiagnosis (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 (a) Diagnosis is not always straightforward as seen in this second primary molar with deep caries and pain of short duration. A vital pulpotomy was planned because the tooth’s pulp was judged as vital. (b) Same tooth 11 months after formocresol pulpotomy showing failure from misdiagnosis.

The only way to accurately diagnose the degree of the pulp’s inflammation is histologically. There is almost no correlation between the clinical symptoms the child presents with and the histopathologic condition of the tooth, which complicates diagnosis of pulpal health in children (Mass et al., 1995). A patient may present with signs and symptoms that indicate reversible pulpitis, while if the pulp was histologically examined would demonstrate changes equivalent to chronic total pulpitis and need a pulpectomy or extraction (Seltzer et al., 1963).

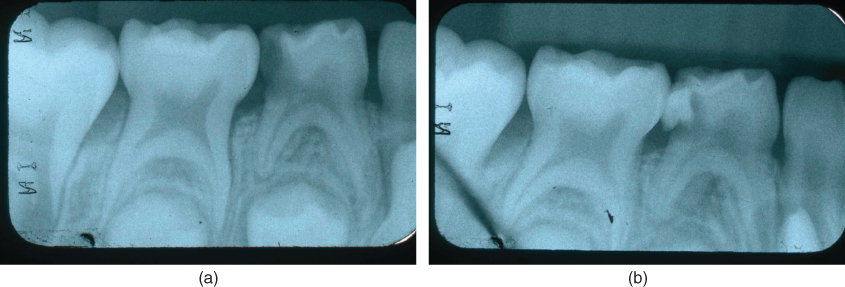

A new clinical adjunct to help the clinician reliably determine the pulp’s vitality was recently published. Coll et al. (2013) studied 117 primary molars with deep carious lesions that were planned to have vital pulp therapy treatment. It was found that by using a glass ionomer interim therapeutic restoration (ITR) before treatment for 1–3 months accurately diagnosed the primary molar’s pulp vitality in 94% of the cases compared to 78% of the teeth when no ITR was used. For teeth with pain, there were 18 patients who presented with pain as the chief complaint, which was not reported by Coll et al. (2013). In these18 patients, the dentist was not sure if the pain was reversible or irreversible pulpitis. All received ITRs, and 17 of the 18 (94%) were correctly diagnosed with either reversible or irreversible pulpitis. Using a glass ionomer ITR for 1–3 months will reliably diagnose the vitality of those molars with deep caries. If the tooth’s pulp is irreversibly inflamed or necrotic after ITR, it will show either a fistula, obvious radiographic signs, or pain (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 (a) Pretreatment radiograph of a mandibular first primary molar without soft tissue swelling but an unclear history of pain that made the dentist unsure of the diagnosis. An interim therapeutic restoration using glass ionomer cement was placed. (b) One week later, the patient had a gingival swelling without pain, finalizing the diagnosis as irreversible pulpitis.

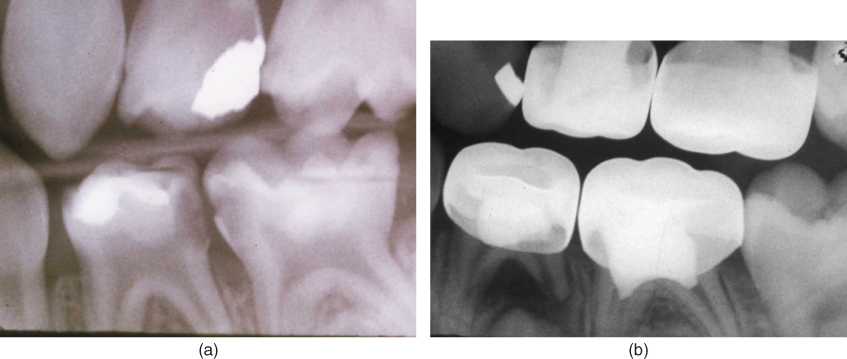

One unpublished radiographic finding concerns distal caries in lower primary first molars. If the bitewing shows the caries radiographically into the pulp, it appears from my experience that the pulps of these teeth are irreversibly inflamed, as pulpotomies appear to fail in these situations. From my clinical experience and research I conducted (Coll et al. 2013), distal radiographic decay into the pulp on a bitewing radiograph in mandibular primary first molars is usually irreversibly inflamed or necrotic (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 (a) Pretreatment radiograph of a mandibular first primary molar with distal caries radiographically into the pulp patient age 4.5 years. No interim therapeutic restoration was placed, and a vital formocresol pulpotomy was performed because pulpal bleeding was controlled with a cotton pellet. (b) Same first primary molar showing formocresol pulpotomy failure 24 months later. The tooth’s pulp had irreversible pulpitis, which was not clinically apparent and is a contraindication for vital pulp treatment.

Clinical evaluation and history

The clinical evaluation involves assessing the child for signs and symptoms of irreversible pulpitis or necrosis clinically or by history. This will include an extraoral examination asking about and looking for facial swelling or tenderness. Question the caregiver as to a history of fever, and if needed, use a thermometer to check for any elevation in temperature. Questioning the child in most cases will not always yield reliable information as to the history of pain. Ask the parent or caregiver “Has your child awakened in the middle of the night like at two AM with pain”? Do not simply say “Has your child awakened with pain at night”? A cavitated lesion in a primary molar may cause pain at bedtime but not have irreversible pulpitis. The child can have a snack at bedtime and go to bed without brushing the teeth. A reversibly inflamed pulp can then cause the child to complain of “pain at night,” which is not spontaneous pain. As stated previously, the duration of pain in a primary tooth is not a critical assessment as to the degree of pulpal inflammation (Farooq et al., 2000). A large cavitated lesion in a primary molar can get a gummy candy or food lodged in it and cause pain for an extended duration in a child, but the pulp may not be irreversibly inflamed. The history of the present toothache in my opinion is the most important information the dentist can obtain to determine the vitality of the tooth.

Percussion, mobility, and pulp tests

After completing the history, perform an intraoral examination of the area of concern. Be aware that a parent can claim that pain is in the lower right because they see a carious lesion in their child’s lower right first primary molar. The child may have held his or her hand on the right side of the face and said his or her tooth hurt. The parent may mistakenly assume that the pain is from the lower right first primary molar. However, the pain is actually from a maxillary right molar the parent never looked at. Look for teeth with caries that show a missing filling, soft tissue redness, fluctuance, or a draining fistula. Percussion can be a valuable aid in diagnosing whether the tooth has irreversible pulpitis due to the infection, causing pressure in the periodontal ligament (PDL). However, the reliability of the child’s response has to be assessed due to apprehension and the child’s maturity. I recommend using a finger to press on a nonsuspicious tooth first. Then, press on the suspicious tooth and look for any sign of discomfort in the child’s expression. Do not use an instrument handle to tap on the tooth because this can be misunderstood in a child as pain. Tooth mobility in an infected primary incisor may be the only clinical sign of dental infection, especially if diagnostic radiographs are unable to be taken. Maxillary primary incisors in children younger than 4 years that are mobile with large caries are likely infected. The dentist must be aware of physiologic root resorption, but a slightly mobile primary molar in a child aged 6 years or younger would indicate an abscess. However, many infected primary molars do not exhibit mobility. Other pulp tests for primary teeth such as cold, hot, and electric pulp tests are of little use in children due to the unreliable responses (Camp, 2000; Flores et al., 2007).

Tooth color change

A tooth color change occurring in primary incisors after trauma in many cases does not indicate necrosis. Holan (2004) studied 97 primary incisors that exhibited dark discoloration after trauma. In 52% of the dark incisors, the color became yellowish, while 48% remained dark. Clinical signs of infection were associated with the incisors that remained dark. The teeth that lightened in color showed pulp canal narrowing or obliteration, but in most cases no infection. In addition, of the incisors that retained their dark color, Holan (2004) reported that 50% remained clinically asymptomatic and exfoliated even if they showed accelerated root resorption. I did a study on primary incisor trauma that I never published. It was a retrospective analysis of 45 teeth, with concussion blows followed a mean of 47 months. The parents brought most of the children 7–14 days after trauma because most presented with a gray color within 1 month after trauma. After their final examination or a minimum of 24 months, 86% was a normal or light yellow color and radiographically showed narrowing or obliteration of their root canals. So, in diagnosing traumatized primary incisors for pulp treatment, watchful waiting is a good rule, and if a fistula or other sign of pulp infection is seen, then perform treatment. Be aware, a pulpectomy in a dark primary incisor does not lighten the tooth’s color. An avulsed primary teeth should not be reimplanted and have a pulpectomy performed (Flores et al., 2007).

Pulpal bleeding

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses