38 Principles of Facial Reanimation Surgery

Direct Facial–Facial Nerve Reconstruction

Facial–Facial Nerve Interpositional Graft

Hypoglossal–Facial Nerve Jump Anastomosis and Combined Approach

Dynamic Procedures with Regional Muscle Transposition

Electrostimulation and EMG Biofeedback Therapy

Introduction

In patients with salivary gland diseases who develop facial palsy, the cosmetic results are due to atrophy of the facial muscles resulting from nerve degeneration in the extratemporal portion of the nerve within the parotid salivary gland, either involving the nerve trunk or occasionally the peripheral nerve branches. The timing of treatment for patients with this type of facial palsy generally falls into two distinct categories:

1. Acute facial palsy resulting from a radical parotidectomy or submandibular gland excision, which occurs mainly in patients with salivary gland cancer; or less frequently, facial palsy due to trauma or following elective surgery—iatrogenic lesions.

2. Patients who present with chronic facial muscle atrophy much later, months to years after the onset of the facial palsy, usually if the palsy was not immediately corrected, if surgical rehabilitation was not offered, or if nerve reconstruction was considered to be not technically possible.

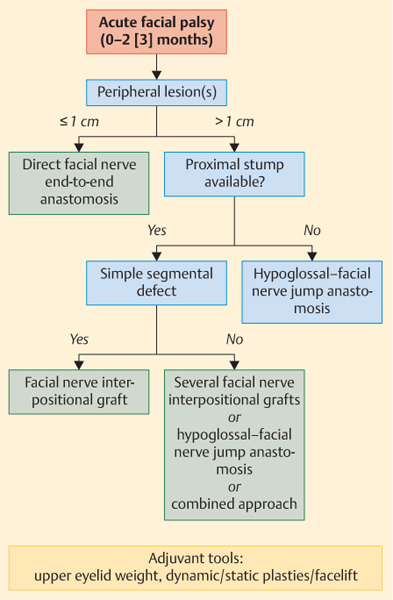

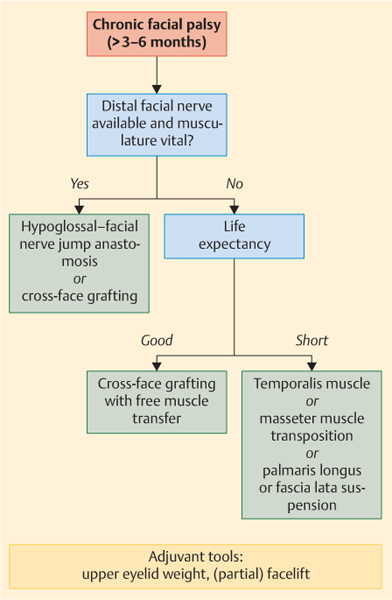

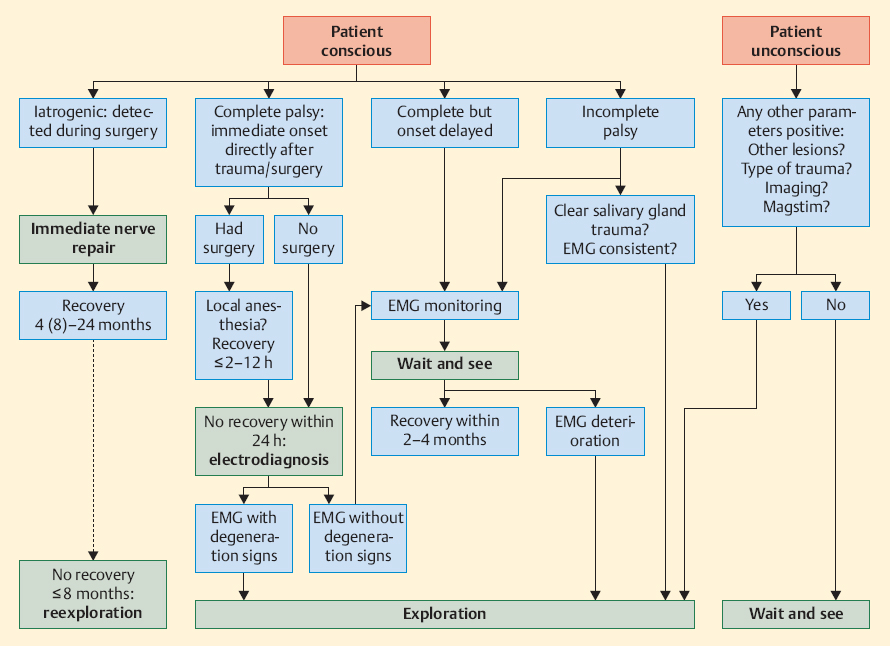

Figures 38.1, 38.2, 38.3 present algorithms summarizing the indications for surgical procedures and when such procedures are likely to lead to cosmetic improvement.1–4

Patients basically fall into two categories, with different rehabilitation and reconstruction approaches needed in each: those with acute palsy of the facial nerve and those with chronic palsy.

Patients basically fall into two categories, with different rehabilitation and reconstruction approaches needed in each: those with acute palsy of the facial nerve and those with chronic palsy.

Direct Facial–Facial Nerve Reconstruction

Patient Selection

Direct nerve repair using an end-to-end nerve suture is only possible if the defect is less than 1 cm. In cases involving cancer, the nerve stumps have to be definitely proven to be tumor-free before any rehabilitative surgery is started. The majority of these cases are traumatic or iatrogenic, with sharply cut nerve ends involving the peripheral nerve or the nerve trunk itself. The best results are achieved if direct nerve repair can be undertaken immediately, with a tension-free nerve anastomosis. Direct nerve repair after a delay is possible within 6 months (or better still within 2 months), and this leads to restoration of some nerve function. Immediate repair yields the best results.

Patient Information and Consent

The patient has to be informed that functional failure is a possible outcome, with additional revision surgery being needed occasionally. The patient must understand that complete nerve regeneration may take 6–18 months (depending on the site of the lesion).

Anesthesia and Positioning

General anesthesia is mandatory. The patient is placed in a supine position, with the head rotated to the opposite side.

Fig. 38.1 Decision-making algorithm in patients with salivary gland disease and acute facial palsy due to a peripheral facial nerve lesion.

Fig. 38.2 Decision-making algorithm in patients with salivary gland disease and chronic facial palsy due to a peripheral facial nerve lesion that has lasted more than 3–6 months.

Surgical Steps

Wide surgical exposure of the lesion site is essential, exposing an area with a radius no less than 4 cm to confirm that the nerve has been injured or divided at one site only. Use of a surgical microscope (or at least magnification loupes) is essential to identify the facial nerve and its branches. In cases of traumatic origin, meticulous wound rinsing is mandatory to ensure that the wound, tissues, and nerves do not dry while exposed under the high-energy lighting systems. In tumor cases, tumor-free nerve stumps have to be confirmed by frozen section or definitive histology.

The nerve endings affected are freshened and the epineurium is cut back a short distance before any nerve suture is inserted.

The human peripheral facial nerve is a monofascicular nerve—i.e., an epineurial nerve. Suturing is carried out with four to six individual stitches with nonabsorbable monofilament 8–0to11–0 suture material, depending on the caliber of the nerve being repaired. Bulging or bunching at the suture line has to be avoided in the nerve anastomosis, as this suggests that the sutures have been tied too tightly across the anastomosis line, and also to ensure that the anastomosis and the nerves remain lax and tension-free.

Tips and Tricks

Tips and Tricks

Gentle mobilization of the nerve stumps reduces tension on the suture site.

Gentle mobilization of the nerve stumps reduces tension on the suture site.

The use of releasing sutures in the soft tissues or muscles surrounding the nerve stumps can help reduce the anticipated tension across the suture line.

The use of releasing sutures in the soft tissues or muscles surrounding the nerve stumps can help reduce the anticipated tension across the suture line.

Because of the mobility of the neck anatomy and soft tissues, suturing of the nerve is preferable to using fibrin glue.

Because of the mobility of the neck anatomy and soft tissues, suturing of the nerve is preferable to using fibrin glue.

In cases due to trauma with salivary gland laceration, and if primary suturing is not possible because the patient has comorbid conditions, an attempt should be made to mark the site or ends of the nerve lesion with metal clips, as this will help identify the trauma site subsequently in a later operation, or if the patient is being ventilated.

In cases due to trauma with salivary gland laceration, and if primary suturing is not possible because the patient has comorbid conditions, an attempt should be made to mark the site or ends of the nerve lesion with metal clips, as this will help identify the trauma site subsequently in a later operation, or if the patient is being ventilated.

As a general rule, to establish the best local environment for carrying out microsurgery on a nerve: a circular 1-cm platform can be cut out of the metallic part of the suture package and placed underneath the suture site to stabilize it. Drying out of the nerve stumps should be prevented by regular irrigation with drops of saline.

As a general rule, to establish the best local environment for carrying out microsurgery on a nerve: a circular 1-cm platform can be cut out of the metallic part of the suture package and placed underneath the suture site to stabilize it. Drying out of the nerve stumps should be prevented by regular irrigation with drops of saline.

Fig. 38.3 Algorithm for patients with acute palsy immediately after surgery or trauma, depending on the consciousness status.

Complications

When strict rules for patient selection are observed, the only important complication is that no nerve regeneration takes place, although this is rare.

Measures for Specific Complications

Nerve regeneration is best evaluated using electromyography (EMG), starting after 3 months. Electromyography can detect axon regeneration in the facial expression muscles (mimetic muscles) and increasing regeneration at an early stage, and these signs are detected about 3 months before signs of obvious clinical movement. Electromyography can thus reveal initial signs of regeneration failure, much earlier than clinical examinations during follow-up.5 If no signs of nerve recovery are detected with EMG, then reexploration of the suture line should be discussed with the patient and suggested in preference to waiting for the alternative of using facial rehabilitation techniques at a later stage.

Postoperative Care

According to current findings, electrostimulation of the musculature does not have any positive influence on the extent of reinnervation and it also obstructs electromyographic monitoring during the follow-up, as it produces long-term electrical artifacts in the muscles. Training of the facial expression muscles can begin when the first sign of muscle reinnervation becomes clinically apparent; starting such training early or before muscle activity is evident is only frustrating for the patient.

Outcomes

Direct facial nerve repair gives the best results in comparison with all other rehabilitation procedures.1 The patient achieves a good resting tone and good to satisfactory voluntary movements. All patients develop some degree of defective healing, which may range from mild to severe synkinesis.

Facial–Facial Nerve Interpositional Graft

Patient Selection

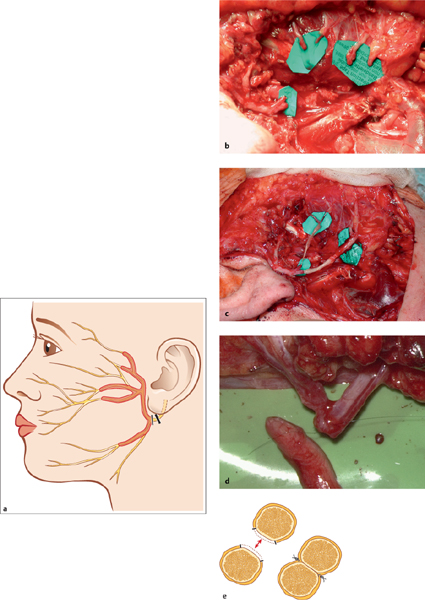

If the peripheral facial nerve defect is more than 1 cm, or in patients with a segmental defect in the facial fan (the predominant defect in parotid cancer patients after radical parotidectomy), facial–facial nerve interpositional grafting results in good facial function (Fig. 38.4 and Fig. 38.8).

Facial–facial nerve interpositional grafting is the most frequently used nerve reconstruction technique in patients with parotid cancer and nerve infiltration.

Facial–facial nerve interpositional grafting is the most frequently used nerve reconstruction technique in patients with parotid cancer and nerve infiltration.

Patient Information and Consent

This is the same as for direct end-to-end-anastomosis, but in addition, the patient should be aware that harvesting of the nerve graft will lead to a loss of sensitivity in the target area of the nerve selected—i.e., numbness in the ear region (the great auricular nerve) or in the dorsal lower leg and lateral foot (the sural nerve). Postoperative infection and wound dehiscence in the leg is possible, but this is seldom encountered if meticulous layered suture closure of the wound is carried out.

Fig. 38.4 a–e Reconstruction of segmental facial nerve defects.

a Surgical rehabilitation: a typical surgical segmental defect in the facial nerve at the end of parotid cancer surgery.

b The proximal and distal nerve endings are pooled and trimmed for nerve suturing.

c Reconstruction with several branches of the great auricular nerve.

d Peripheral thin branches are pooled and sutured together to increase the nerve diameter.

e The epineurium is peeled off in the attachment zone.

Anesthesia and Positioning

General anesthesia is mandatory. The patient is placed in a supine position with the head rotated to the opposite side. If it is necessary to harvest the contralateral great auricular nerve, the head has to be rotated to the ipsilateral side for that part of the operation.

Surgical Steps

The first steps are the same as for direct nerve suture (see above). The great auricular nerve is then identified along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoidal muscle, where it crosses the muscle in a cephalad direction. The nerve is divided at a length distally that will provide as long a nerve graft as is possible. The branching into the anterior and posterior ramus can be harvested as well, if useful for the reconstruction. It is important that the nerve graft should not be crushed or stretched. The graft should be stored between wet cotton or in a wet chamber until required for reconstruction. If the ipsilateral great auricular nerve is not available—e.g., due to tumor infiltration in the neck in parotid cancer patients—the nerve can be harvested on the contralateral side.

The sural nerve is harvested with several transverse 1-cm incisions on the back of the lower leg. The sural nerve can be identified between the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon, lying posterior to the saphenous vein. Here, the nerve lies superior to the deep fascia. The nerve can be followed cranially using blunt dissection or a stripper. Near the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle, a communicating branch to the peroneal nerve branches off before it penetrates the deep fascia between the muscle heads. The stripper typically blocks here.

The graft or several graft pieces are positioned end to end in the segmental defect or defects. Four to six individual stitches with nonabsorbable monofilament 8–0to 11–0 suture material, depending on the nerve caliber, are used for the end-to-end anastomosis to the proximal and distal sides of the graft.

Tips and Tricks

Tips and Tricks

In larger segmental defects, there may be a discrepancy in caliber size between the thick proximal facial nerve stump and the thinner distal stumps, and the discrepancy in the number of nerve branches has to be overcome by pooling of peripheral branches and/or by diversifying the interpositional nerve graft. For pooling, the branches are sutured together side by side (Fig. 38.4).

In larger segmental defects, there may be a discrepancy in caliber size between the thick proximal facial nerve stump and the thinner distal stumps, and the discrepancy in the number of nerve branches has to be overcome by pooling of peripheral branches and/or by diversifying the interpositional nerve graft. For pooling, the branches are sutured together side by side (Fig. 38.4).

The problem of a small caliber discrepancy can also be solved by an oblique incision into the smaller nerve stump to enlarge the cross-section.

The problem of a small caliber discrepancy can also be solved by an oblique incision into the smaller nerve stump to enlarge the cross-section.

One great auricular nerve is sufficient for most defects, even large ones. For large defects, the nerve has to be followed deep down as far proximally as possible into the cervical plexus to obtain a sufficient length for the anticipated graft.

One great auricular nerve is sufficient for most defects, even large ones. For large defects, the nerve has to be followed deep down as far proximally as possible into the cervical plexus to obtain a sufficient length for the anticipated graft.

The proximal stump of the donor nerve has to be ligated to prevent neuroma formation.

The proximal stump of the donor nerve has to be ligated to prevent neuroma formation.

Complications

When strict rules for patient selection are observed, the only important complication is that no nerve regeneration takes place, although this is rare. In such cases, reexploration of the suture site and the alternative of facial rehabilitation have to be discussed with the patient. All patients develop some degree of defective healing, which may range from mild to severe synkinesis.

Measures for Specific Complications

The time course of regeneration is monitored in the same way as after direct nerve suturing to decide whether reexploration is necessary (see above).

Postoperative Care

This is also the same as after direct suturing (see above).

Outcomes

Facial nerve grafting results in good resting tone on the paralyzed side and satisfactory movements, with defective healing.

Hypoglossal–Facial Nerve Jump Anastomosis and Combined Approach

Patient Selection

This type of reconstruction is best selected if the proximal facial nerve is irreversibly damaged, or in patients who present for delayed reconstruction after 6–24 months.

Hypoglossal–facial nerve jump anastomosis is the best nerve reconstruction technique for delayed reconstruction and if the proximal facial stump is not available.

Hypoglossal–facial nerve jump anastomosis is the best nerve reconstruction technique for delayed reconstruction and if the proximal facial stump is not available.

Patient Information and Consent

The information the patient requires is the same as for direct nerve suturing and nerve interposition grafting, since in most cases the great auricular nerve is needed as a jump graft. In addition, there is a theoretical risk of unilateral tongue palsy if too much of the hypoglossal nerve is transected completely or incidentally. This would result in the patient having altered swallowing and speech. When a cranial nerve-to-nerve or cross-nerve anastomosis is being recommended, the patient should be aware that using the spinal accessory or phrenic nerve leads to a much poorer functional outcome. Cross-facial nerve grafting is an alternative, mostly used in combination with a free muscle transfer (see below).6,7 A follow-up period of at least 18 months is necessary for evaluation of successful facial nerve recovery.

Anesthesia and Positioning

General anesthesia is mandatory. The patient is placed in a supine position with the head rotated to the opposite side. The ipsilateral neck has to be exposed to allow the approach to the hypoglossal nerve.

Surgical Steps

The first steps in dissecting the distal facial nerve stump or branches are the same as for direct nerve suture (see above). The great auricular nerve is dissected in the same way as for interposition grafting. A graft of about 5 cm is needed.

To identify the hypoglossal nerve, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is retracted superiorly and the internal jugular vein posteriorly. The nerve is isolated on the undersurface of the digastric muscle, about 1–2 cm distal to the descending hypoglossal branch. The hypoglossal nerve is incised about 1 cm distal to this branch, cutting not more than one-third horizontally.

The graft of the great auricular nerve is trimmed to the distance between the incision in the hypoglossal nerve and the distal facial nerve or nerve branches; any tension on the graft should be avoided (Fig. 38.5 and Fig. 38.8). The proximal end of the graft is sutured end-to-side to the proximal opening of the hypoglossal nerve with four sutures (using nonabsorbable monofilament 8–0to11–0 suture material). The distal end of the graft, or several branches of it if necessary, is sutured end-to-end to the facial nerve main trunk or distal facial nerve branches with four to six sutures.

In the combined approach (Fig. 38.5), a hypoglossal–facial jump anastomosis can be combined optionally with a facial nerve interpositional graft. This is an optimal technique for reconstructing larger segmental defects when the proximal facial nerve stump is still available. In such cases, the upper face branches are reconstructed with a graft or grafts to the proximal facial nerve stump, and the lower face is reconstructed with a jump graft to the incised proximal hypoglossal nerve.

Tips and Tricks

Tips and Tricks

Some authors have described a jump anastomosis without interpositional grafting, in which the hypoglossal nerve is placed directly onto the facial nerve. In patients with parotid cancer, the defect is normally too large for such an approach. If this is attempted, one should be prepared to use an interpositional graft.

Some authors have described a jump anastomosis without interpositional grafting, in which the hypoglossal nerve is placed directly onto the facial nerve. In patients with parotid cancer, the defect is normally too large for such an approach. If this is attempted, one should be prepared to use an interpositional graft.

To identify the main trunk of the hypoglossal nerve clearly, electrostimulation should be used and the descending hypoglossal branch should be dissected.

To identify the main trunk of the hypoglossal nerve clearly, electrostimulation should be used and the descending hypoglossal branch should be dissected.

In the majority of cases, a hypoglossal graft is best placed and positioned on top of the digastric muscle. Occasionally, however, it is best to test the best position, either under or on top of the digastric muscle.

In the majority of cases, a hypoglossal graft is best placed and positioned on top of the digastric muscle. Occasionally, however, it is best to test the best position, either under or on top of the digastric muscle.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses