Use Brackets Designed for Specific Prescriptions

The Alexander Discipline bracket prescription dates back to the 1970s. Prior to introducing pretorqued brackets in the 1970s, I began saving finishing archwires to measure for torques, offsets, and angulations that had been hand bent in each case. These measurements were the basis for the design of the first appliance prescriptions. This design strategy —that is, beginning with the end result and working backward—has been further refined throughout years of trial, error, and clinical research, and it has allowed the placement of teeth in specific positions that will have the greatest potential for optimal esthetics and long-term stability.

Distinctive Bracket Design Concepts

Bracket slot size and torque control

To obtain effective torque control, three options are available:

- “Fill up” the bracket slot. In a 0.022-inch slot, the logical archwire is a 0.021 × 0.025-inch archwire, which would provide the same torque control as a 0.017 × 0.025-inch archwire in a 0.018-inch slot.

- Place certain torque in the archwire.

- Place certain torque in the bracket slot.

It should be understood that for every 0.001 inch of freedom between the archwire and the vertical bracket slot, approximately 5 degrees of effective torque is lost. This means that if the final archwire is a 0.019 × 0.025- inch archwire in a 0.022-inch slot, 15 degrees of torque is lost. A 0.017 × 0.025-inch archwire in a 0.018-inch slot would create a loss of 5 degrees.

The 0.018-inch slot dimension was selected over the 0.022-inch slot dimension for three reasons: better torque control, better leveling mechanics, and patient comfort. First, accurate torque control for the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth is achieved by finishing each case with a 0.017 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwire, which results in nearly complete engagement of the bracket slot to the archwire. Eliminating the 5 degrees of freedom from the bracket’s torque value results in more effective transmission of torque to the tooth. Second, the additional interbracket space (discussed later) allows stiffer archwires with accentuated curves to be placed earlier in treatment. The result is more efficient leveling mechanics. Third, the patient’s discomfort is reduced by use of the smaller archwires in the 0.018-inch slot bracket with greater interbracket space.

Use of single brackets instead of twin brackets

Whereas some bracket prescriptions use twin brackets on all teeth except for the molars, it seems to make more sense to use single brackets specifically designed to fit the shape of each tooth.

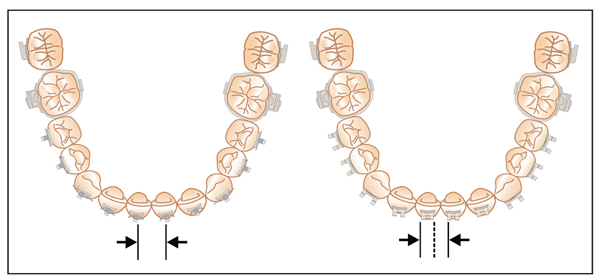

In the Alexander Discipline, twin brackets are used only on large, flat-surface teeth. The use of single brackets with rotation wings on larger, flat-surface teeth may be beneficial if these teeth require significant rotation. Single brackets, which create more interbracket space (Fig 6-1), are always used on small, flat-surface teeth and on curved-surface teeth (Fig 6-2).

Fig 6-1 Increased interbracket distance. Almost 50% more interbracket distance is obtained with single versus twin brackets.

Fig 6-2 Single-wing brackets. These are used on small, flat-surface teeth and on all curved-surface teeth.

Interbracket space

Increasing the distance between brackets has a significant impact on treatment: The teeth quickly come into alignment early in treatment with little discomfort to the patient.

Everyone knows that a small change in archwire length or diameter produces significant change in the wire’s load-deflection rate. For example, doubling the interbracket distance—and hence the interbracket wire length—can result in an eightfold reduction of the force delivered by wires of the same type and size. Similarly, if the same kind of archwire is used in two patients, one with twin brackets and the other with single brackets with wings, the interbracket distance is effectively doubled in the second patient relative to the first. Consequently, the amount of force delivered to the teeth could be eight times lower in the patient with the single brackets with rotation wings. Such a sizeable reduction in force levels could also reduce the extent of undermining resorption and related discomfort experienced by the patient.

As interbracket distance increases, larger-diameter rectangular archwires can be engaged with no additional force. Because of the resulting decrease in the interbracket load-deflection rate, fewer archwire changes are needed, and finishing archwires may be used sooner in treatment. A relative reduction in torsional stiffness allows earlier placement of rectangular archwires, providing greater and faster torque control.

Single brackets with wings offer other advantages as well. The archwire is simpler to engage and ligate, and a larger archwire may be placed without additional discomfort to the patient.

Rotation wings

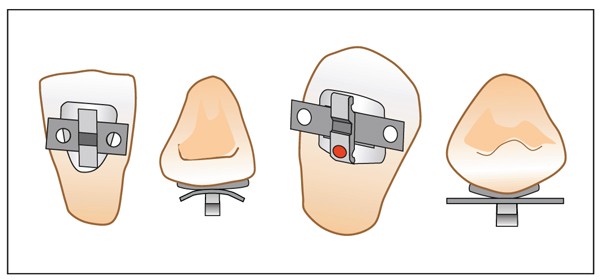

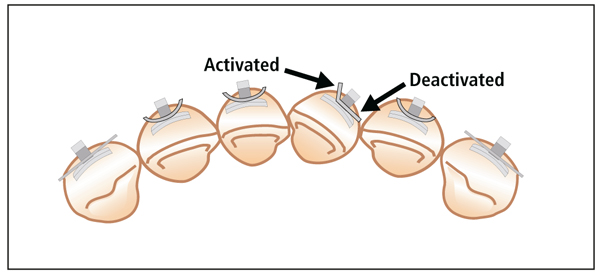

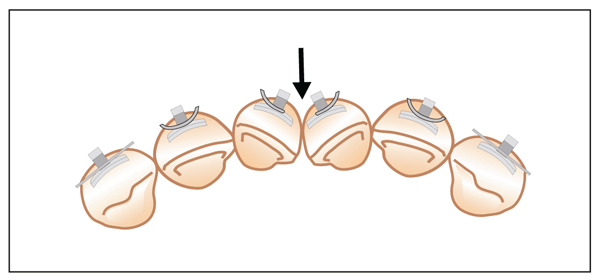

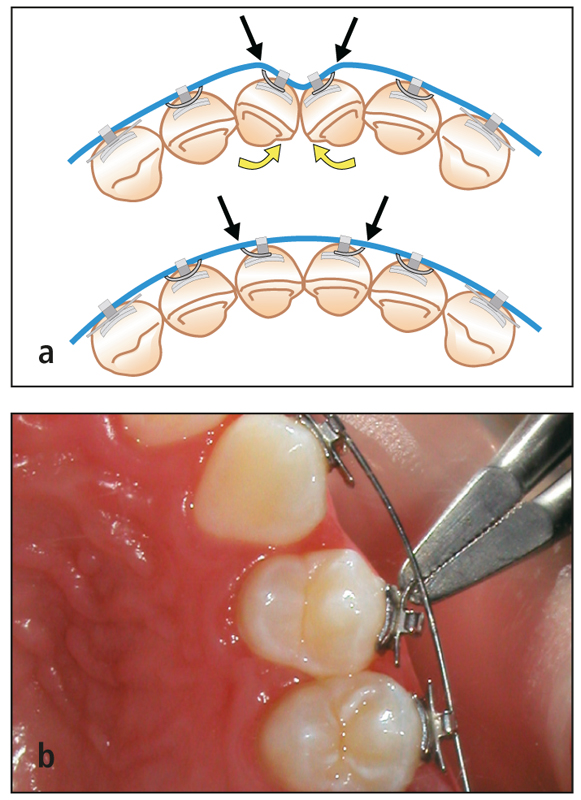

Rotation wings provide specific advantages not found with twin brackets: faster rotational correction; more precise rotational control; wing activation for controlled deactivation and/or overcorrection (Fig 6-3); and wing removal for more accurate bracket placement in crowded dentitions (Fig 6-4).

Because the force is applied only to the active wing, there is no need to replace the bracket to hold the rotational correction if a wing has been removed (Fig 6-5a).

Contrary to what some orthodontists believe, rotation wings do not require routine activation. If the bracket is properly positioned, there is usually no need to activate or remove a rotation wing. When activation of a rotation wing is necessary, the following technique is recommended. A Weingart pliers or other similar pliers is placed so that its beaks are at an angle on the wing to be activated (Fig 6-5b). As the pliers are squeezed, the rotation wing will bend at the hole in the wing. Rotation wing activation will not cause bracket debonding.

Fig 6-5 (a) No need to replace a bracket when a wing has been removed. (b) Weingart pliers for activation of a rotation wing.

Generally, all rotations should be corrected while the patient is wearing the initial archwires, which are more resilient. If a rotation still remains when the patient is wearing the stiffer finishing archwire, minor rotational corrections can sometimes be made; to correct a more significant rotation, however, it may be necessary to return to a more resilient archwire.

Bracket Prescription

Offsets, angulations, and torques are designed into the Alexander bracket prescription appliances, which position the teeth in esthetic, functional, and stable positions regardless of the original malocclusion. The prescription for using the bracket system follows.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses