There Are No Little Things

A popular motivational book published in the United States is entitled, Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff.1 In the world of orthodontics, however, this is poor advice. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Stephen R. Covey captured the nation’s attention with the principles he espoused in his book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, which was first published in 1989.2 Covey focused on specific habits that anyone could adopt to become more effective. I agree with most of Covey’s ideas, but a favorite is the following (based on a quote from American author Bruce Barton): “Sometimes when I consider what tremendous consequences come from little things, I am tempted to think there are no little things.”

In my first book,3 chapter 2 was devoted to a discussion of the “little things” that make all the difference in orthodontic practice. Although computers have replaced pen and paper, the basic concepts remain the same. Orthodontists must envision the “big picture” in their practice and yet to be successful, they must also tend to all of those little things that, when put together properly, give the final rewarding result.

This book focuses on the biomechanics of orthodontic treatment as well as patient compliance. However, for treatment to be successful, office management and patient treatment mechanics cannot be separated. The more efficient an orthodontist is in treatment mechanics, the more smoothly the whole office can function.

The following chapters describe and illustrate each of the little things that should be routinely performed for consistently high-quality results. The outcome of any therapeutic orthodontic procedure depends on proper diagnosis, treatment planning, and management of any skeletal problems. Then it is possible to begin the process of treatment, including selection of the right bracket system, detailed placement of brackets, archwire sequence, use of elastics, finishing, and finally, retention. If the principles involved in each of these steps are understood and performed properly and routinely for each patient, the final results will include consistently beautiful smiles, good functional occlusion, healthy hard and soft periodontal tissues, and long-term stability.

Optimum Treatment Timing

Of all the little things that influence the outcome of treatment, timing may be one of the most important. How does a clinical orthodontist make the very important decision as to when to initiate treatment?

Issues to Consider

While observing cervical maturation can be helpful, one day the profession may have a simple test to accurately pinpoint a patient’s stage of growth. For now with growing children, the orthodontist must approach every appointment as if the child is a new patient, because new growth and the treatment mechanics being employed will have altered the prior condition.

Stage of growth

From the orthodontist’s perspective, the best time to treat patients is when they are in a period of maximum growth. It is always satisfying to see very difficult cases managed with beautiful results that are achieved partly because of good timing between treatment and growth. Excellent results can often be attributed as much to growth as to the skill of the treating practitioner. The converse situation also occurs too often—that is, orthodontists tend to blame “bad growth” for poor results.

Age

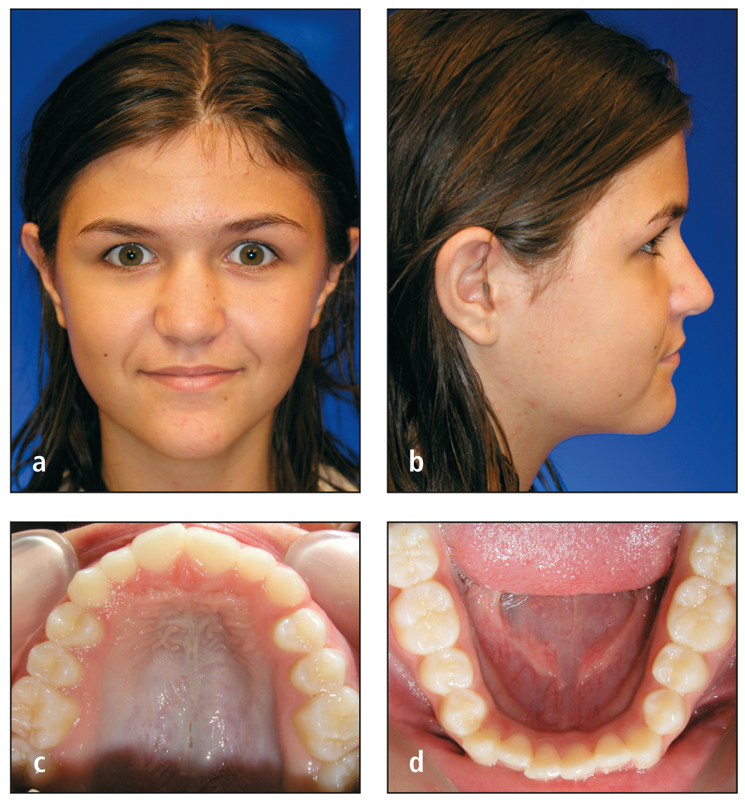

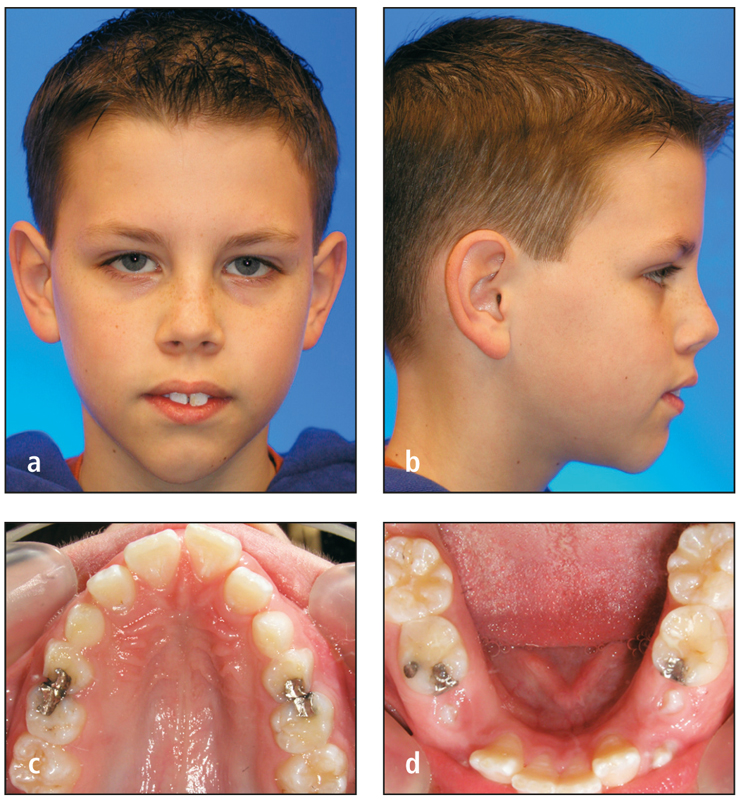

Generally, girls begin growth at an earlier age than boys. For example, an 8-, 9-, or 10-year-old girl usually responds better to headgear treatment than does a boy of the same age. However, girls also complete their growth at an earlier age. Boys, therefore, respond best to orthopedic changes between 12 and 14 years of age. Figures 2-1 and 2-2 demonstrate the gender difference in dental maturity of two patients of the same age.

Figs 2-1a to 2-1d Adolescent girl, age 12 years, 2 months, presents with full permanent dentition including second molars. The patient is ready for treatment.

Figs 2-2a to 2-2d Adolescent boy, age 12 years, 5 months, demonstrates a mixed dentition with 8 primary teeth present. Consider a mandibular lingual arch, then recall in 6 months.

Nevertheless, the window of opportunity for capitalizing on growth in children has great individual variation that/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses