Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is chronic and frequently associated with exacerbations and remissions of clinical signs and symptoms. Clinicians should use pathologic and immunonologic techniques to help diagnose patients. Multidisciplinary collaboration is often necessary for the diagnosis and proper treatment of MMP. Systemic adjuvant immunosuppressive therapy is necessary for patients with progressive disease. In spite of the advances in available immunosuppressive medications and biologics, scarring is a significant complication in many cases. Surgical intervention is not curable; however, it may be necessary for restoring function and improving quality of life.

Key points

- •

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a heterogeneous subepithelial blistering disease predominantly affecting oral, ocular mucous membrane and occasionally the skin.

- •

Like other forms of pemphigoid, the disorder is characterized by the formation of autoantibodies against structural proteins of the dermal-epidermal junction.

- •

Early diagnosis is critical and immunosuppressive treatment may prevent scarring.

Introduction

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is a heterogeneous group of chronic, autoimmune subepithelial blistering diseases that predominantly involves the mucous membranes and occasionally the skin. In vivo, it is characterized by linear deposition of immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgA, or C3 along the epithelial basement membrane zone.

Although the oral and ocular mucosae are the most common sites affected, the nasopharynx, esophagus, larynx, and anogenital region also may be involved. This disorder results in mucosal and/or skin blistering, ulceration, and subsequent scarring. The disease severity and distribution are highly variable, from mild cases involving only the oral mucosa, to severe cases involving the ocular, genital, and esophageal mucosa. Involvement of the larynx or esophagus can give rise to strictures, which may be life-threatening. Because the consequences of this disease can be severe and limited therapeutic options are available once scarring develops, early diagnosis is critical. However, as the disease is rare and the early presenting symptoms are nonspecific, MMP is often unrecognized in the early inflammatory stage.

Other nomenclatures for MMP include cicatricial pemphigoid, oral pemphigoid, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), ocular pemphigoid, and benign mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Autoantibodies to one or several autoantigens in the mucosal or epithelial basement membrane zone (BMZ) have been identified in patients with MMP. The association of MMP with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) major histocompatibility class II HLA-DQB1*0301 has been demonstrated. The cause is usually unknown, but there are a few reports of MMP triggered by medications, such as methyldopa, clonidine, and d -penicillamine.

Introduction

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is a heterogeneous group of chronic, autoimmune subepithelial blistering diseases that predominantly involves the mucous membranes and occasionally the skin. In vivo, it is characterized by linear deposition of immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgA, or C3 along the epithelial basement membrane zone.

Although the oral and ocular mucosae are the most common sites affected, the nasopharynx, esophagus, larynx, and anogenital region also may be involved. This disorder results in mucosal and/or skin blistering, ulceration, and subsequent scarring. The disease severity and distribution are highly variable, from mild cases involving only the oral mucosa, to severe cases involving the ocular, genital, and esophageal mucosa. Involvement of the larynx or esophagus can give rise to strictures, which may be life-threatening. Because the consequences of this disease can be severe and limited therapeutic options are available once scarring develops, early diagnosis is critical. However, as the disease is rare and the early presenting symptoms are nonspecific, MMP is often unrecognized in the early inflammatory stage.

Other nomenclatures for MMP include cicatricial pemphigoid, oral pemphigoid, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), ocular pemphigoid, and benign mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Autoantibodies to one or several autoantigens in the mucosal or epithelial basement membrane zone (BMZ) have been identified in patients with MMP. The association of MMP with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) major histocompatibility class II HLA-DQB1*0301 has been demonstrated. The cause is usually unknown, but there are a few reports of MMP triggered by medications, such as methyldopa, clonidine, and d -penicillamine.

Epidemiology

The true incidence of MMP is unclear. A recent study from the United Kingdom demonstrated that ocular MMP accounted for 61% of the cases of newly diagnosed cicatricial conjunctivitis and the incidence was calculated as 0.8 per million population. The incidence of MMP was estimated to be 1.3 to 2.0 per million per year in France and Germany. MMP predominantly affects women more often than men with a female-to-male ratio of nearly 2:1. MMP mainly occurs in the elderly population, commonly observed between 60 and 80 years of age. Albeit rare, children may also be affected. Approximately 20 cases of childhood-onset MMP have been reported, among whom the youngest one was 10 months old. There is no known racial or geographic predilection.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MMP is complex. MMP has been found to be heterogeneous with several different antigens implicated. The pathogenic relevance of autoantibodies in MMP has been demonstrated in vivo and in vitro.

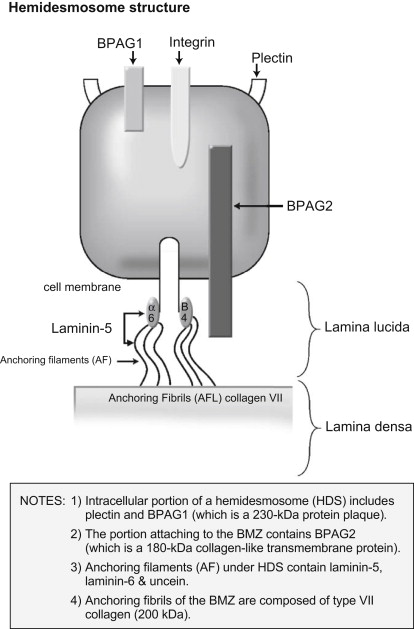

Circulating IgG and/or IgA autoantibodies against components of the BMZ found in the serum of patients with MMP indicate that MMP is mediated by a humoral immune response. Loss of immunologic tolerance to structural proteins in the BMZ results in development of autoantibodies. By use of immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation techniques, a variety of autoantigens, including the bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BPAg1) (a 230-kDa protein, BP230), the bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BPAg2) (a 180-kDa protein, BP180), integrin subunits α6/β4, laminin-332 (also called epiligrin and laminin-5), laminin-6, and collagen type I have been identified ( Table 1 ). BPAg1 is an intracellular protein, whereas BPAg2 and α6/β4 integrins are transmembrane proteins. The most frequently targeted autoantigen in MMP is BPAg2. Laminin-5 is thought to be the major ligand between the transmembrane proteins and the anchoring filaments. Anchoring fibrils, composed of type VII collagen, are located deeper in the lamina densa ( Fig. 1 ). These autoantigens are not exclusive to MMP. Autoantibodies to both BPAg1 and BPAg2 can be present in BP, although BPAg2 is more common, and autoantibodies to type VII collagen are also found in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

| Autoantigens | Location |

|---|---|

| BPAg2 (BP180) | Hemidesmosome/Lamina lucida (transmembrane) |

| BPAg1 (BP230) | Hemidesmosome (intracellular) |

| Integrin subunits α6/β4 | Hemidesmosome (transmembrane) |

| Laminin-5 (laminin-332/epiligrin, α-3, β-3, γ-2 chains) | Lower lamina lucida |

| Laminin-6 | Lower lamina lucida |

| Type VII collagen | Lamina densa/Sublamina densa |

An antibody-induced complement-mediated process results in epithelial detachment. Passive transfer studies in newborn mice have shown that antibodies to BPAg2 induce subepidermal blisters by an inflammatory mechanism. This interaction triggers immunologic events that result in the expression of inflammatory mediators that induce migration of lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells to the BMZ. The separation of epithelium from the underlying tissue within the BMZ results from either direct cytotoxic action or the effect of lysosomal proteolytic enzymes.

Passive transfer studies of antibodies against laminin 5 induce noninflammatory subepidermal blisters, which indicate that anti-laminin 5 IgG is pathogenic, although the mechanism is not clear. Anti-α6 antibody produced separation of epithelium from basement membrane.

Fibroblasts also are activated secondary to the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), which is known to induce fibrosis. The collagen produced may lead to scarring.

Several studies have shown a predominance of CD4 + T-cell and Langerhans cell infiltrates in the conjunctiva of patients with MMP, which indicated the involvement of cellular immunity in the pathogenesis of MMP. The presence of Th17 lymphocytes in conjunctival biopsies was significantly increased in patients with OCP.

Clinical presentation

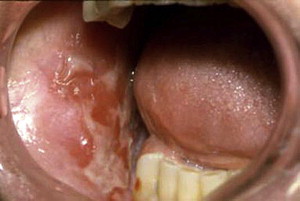

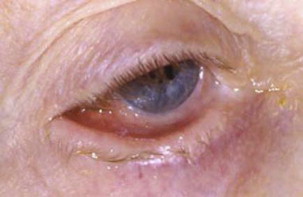

MMP can affect multiple mucosal sites, occasionally with skin involvement. It is a chronic, progressive condition that most frequently involves the oral mucosa (85% of patients), followed by ocular conjunctiva (65%), nasal mucosa (20%–40%), skin (25%–30%), anogenital area and/or pharynx (20%), larynx (5%–15%), and esophagus (5%–15%) ( Figs. 2–4 , Table 2 ). Lesions occurring at any site may heal with scarring.

| Sites Involved | Presentations and Potential Complications |

|---|---|

| Skin | In 25%–30% of patients Localized erythematous plaque near affected mucosal surfaces, generalized bullous eruption particularly on the head and upper body, or vegetating lesions occasionally Scarring, cicatricial alopecia on the scalp |

| Oral cavity | In more than 85% of patients Desquamative gingivitis, erosions, ulceration (see Fig. 1 ) Pseudomembrane Vesicles rarely seen (see Fig. 2 ), bleeding Pain and inability to eat certain types of food Self-limiting mostly Mild scarring or atrophy, intraoral adhesion, loss of teeth rarely |

| Eye | The second most common site (in 65% of patients) Nonspecific conjunctivitis Erosions, corneal damage Photophobia and photosensitivity, dryness Progressive process leading to scarring Symblepharon (see Fig. 4 ), ankyloblepharon, trichiasis, entropion Blindness in close to 15% of patients |

| Nose | In 20%–40% of patients Discharge, erosion, excessive crust Scarring Breathing difficulty |

| Larynx | In 5%–15% of patients Sore throat, hoarseness Scarring, stenosis of airway Breathing difficulty |

| Esophagus | In 5%–15% of patients Dysphagia, odynophagia, esophageal reflux Stricture formation Disability in eating Death |

| Anogenital area | In 20% of patients Erosion and ulceration Bleeding Pain Dysuria Sexual dysfunction |

There is a great variability in the presentation and severity among patients with both localized and extensive involvement. Localized disease can progress to extensive disease. Those who have the disease affecting only the oral mucosa and/or the skin with less tendency of scarring with minimal clinical significance are defined as “low-risk.” On the contrary, “high-risk” patients are those who have disease occurring in any of the following sites: ocular, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, laryngeal, and genital mucosa. The high tendency of MMP to scar in these sites is associated with a poor prognosis in spite of medical treatment. The ocular involvement can result in blindness. Scarring of the laryngeal mucosa can result in sudden asphyxiation, scarring of the esophagus can influence food taking, and scarring of the anogenital mucosa can significantly affect the patients’ daily activities.

An appropriate scoring system can be used to assess the activity and damage of MMP disease and evaluating management outcome. Although there are several ocular grading systems for the severity of MMP, including Foster, Mondino, and Tauber, none of these systems is universally accepted. Reeves and colleagues recently reported a grading system for both oral and ocular involvement, and no correlation in severity was found between the oral and ocular disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

The first international consensus statement on MMP recommended the diagnostic criteria must be based on clinical presentation as well as the presence of certain immunopathologic features ( Table 3 ).

| Clinical features | Chronic, inflammatory, blistering disease Predominantly affecting any or all mucous membranes, with or without skin involvement, and with or without identifiable scarring |

| Direct immunofluorescence | Continuous deposits of IgG, IgA and/or C3 in the epithelial BMZ |

Oral lesions usually involve the palate and gingival areas, and also the labial, tongue, and buccal mucosa. The lesions manifest as erythema, erosions, pseudomembrane, and sometimes intact blisters. Frequently the gingival lesions are descriptively referred to as desquamative gingivitis, which can also be seen in lichen planus and pemphigus vulgaris. The common ocular lesions are conjunctival inflammation and erosions, fornices shortening, corneal neovascularization, and scarring. Anogenital lesions present as blisters, erosions, and scarring.

When a patient is suspected of having MMP, tissue samples should be taken for histopathologic evaluation. The diagnostic tissue biopsy technique is important, as the epithelium in these cases tends to dislodge easily from the underlying connective tissue. Improperly handling tissue may render the specimen nondiagnostic.

Specifically, one specimen of lesional tissue, including intact epithelium, should be submitted in formalin for routine histopathologic analysis with hematoxylin and eosin staining. MMP typically demonstrates the subepithelial split with an inflammatory infiltrate of eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, similar to the changes seen in other forms of pemphigoid. A second specimen should be obtained from perilesional tissue or from a site adjacent to a new vesicle or bulla rather than from vesicle, erosion, or ulceration for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and submitted in a buffered hypertonic saline solution, Michele solution. The latter may give a false-negative interpretation because there may be no significant linear staining of immunoglobulin at the BMZ because of the loss of immunoreactants in longstanding lesions. The DIF typically shows a continuous, linear deposition of IgG and/or C3, and sometimes IgA along the BMZ. To ensure consistency, the consensus statement makes specific recommendations for the procedure of taking biopsies to enhance positive results and avoid additional surgical injury.

Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) is used to detect circulating autoantibodies in a patient’s serum. IIF is performed on an epithelial substrate, such as monkey esophagus, rat bladder, human skin, or human buccal mucosa. Early studies using conventional skin substrates failed to show the association between antibody titer and MMP activity, although Setterfield and colleagues demonstrated that titers of circulating IgG and IgA autoantibodies determined by the IIF technique using mucosal substrates might be predictors of disease severity. IIF performed on 1 mol/L salt-split normal human skin substrate, which is separated at the site of the lamina lucida portion of the BMZ can improve the sensitivity. Autoantibodies to BPAg2 and integrin subunits α6/β4 bind the epidermal side (upper lamina lucida); whereas, autoantibodies to epiligrin and type VII collagen bind to the dermal side on salt-split tissue (lower lamina lucida).

Although distinct subgroups of MMP have been identified by use of the advanced immunopathologic and immunochemical techniques, diagnosis should still be made on the basis of clinical presentation combined with pathologic, immunohistologic, and serum antibody analysis.

Subgroups

Some investigators attempted to subdivide MMP into 4 subgroups based on autoantigens and clinical features. For a listing of these groups, please refer to Table 4 .

| Subgroup | Autoantigens | Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|

| Pure ocular involvement | Integrin β4 subunit | High-risk |

| Pure oral involvement | Integrin α6 subunit | Low-risk |

| Mucosal and skin involvement | BP180 | Heterogeneous outcome |

| Multiple mucosal involvement | Heterogeneous autoantigens | Heterogeneous outcome |

Diagnostic Dilemmas

Diagnosis of MMP is often delayed because of the nonspecific presentations in the early stage or inconclusive biopsies.

DIF often is helpful for diagnosis of pemphigoid, but it does not distinguish MMP from other subepithelial blistering dermatosis (SEBDs), such as bullous pemphigoid (BP), epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA), or bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE). Distinction between the SEBDs may be clarified by combining the clinical findings with other sophisticated immunopathologic tests, which are not routinely requested in clinical practice. Circulating antibodies in MMP are less common than in BP. It is difficult to distinguish MMP from BP solely by DIF and IIF because most patients with MMP and BP have BPAg2. More specific immunologic procedures have demonstrated that autoantibodies produced by patients with MMP bind to the C-terminal portion of the BPAG2 antigen, whereas antibodies produced by patients with BP bind to the NC16A domain of the same autoantigen. This finding suggests that the autoantibody response is epitope specific for an antigen. Furthermore, heterogeneous antigens have been identified in MMP. Because autoantibodies to epiligrin and type VII collagen bind to the dermal side on salt-split tissue, IIF cannot differentiate MMP from EBA.

MMP usually can be differentiated from other mucocutaneous diseases, such as lichen planus, erythema multiforme, and pemphigus vulgaris, by routine histopathology. Neither routine histopathology nor immunopathology can differentiate MMP from other subepithelial autoimmune diseases. The differential diagnosis must be made on the basis of combination of clinical and histopathological features ( Table 5 ).

| Entity | Clinical Features | DIF | IIF on Salt-Split Substrate | Immunoblotting | Electromicroscope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMP | Multiple mucosal involvement, scarring, progressive | Linear IgG, IgA and/or C3 along BMZ | IgG antibodies bind to epidermal or dermal side | BP180, BP230, laminin 5, integrin, type VII collagen | Lamina lucida, sublamina densa |

| BP | Rare mucosal involvement and scarring | Linear IgG and/or C3 along BMZ | IgG antibodies bind to dermal side | BP180, BP230 | Intralamina lucida |

| EBA | Blisters induced by trauma | Linear IgG along BMZ | IgG antibodies bind to dermal side | Type VII collagen | Sublamina densa |

| BSLE | Rare scarring, LE symptoms | Linear or granular IgG, IgA and C3 along BMZ | IgG antibodies bind to dermal side | Type VII collagen | Sublamina densa |

Management

Management Goals

The outcome of MMP therapy is related to the involved sites and early treatment. Involvement of ocular esophageal, genital, and laryngopharyngeal mucosa is typically associated with irreversible scarring. The scarring process may be prevented or retarded by early appropriate interventions. The primary goal in the treatment of MMP is to prevent the progression to blindness, strictures, and airway obstruction, thus preserving function and preventing disability.

Large randomized controlled clinical trials in MMP are not available. Treatment should be individualized depending on the severity of disease, age, general health, medical history, and any contraindications to the use of systemic medications. Collaboration of multidisciplinary specialists involving oral medicine experts, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, and gastroenterologists will improve patient outcomes.

Pharmacologic Strategies

The treatment of patients with MMP depends on the disease severity and the involved sites. The “low-risk” patients, those with involvement of oral mucosa and/or skin, may be managed initially with topical therapies. In severe and recalcitrant patients, combination with systemic therapy is necessary. The “high-risk” patients need aggressive systemic therapy with topical treatment. Restoration of function in cases with disabilities is also warranted.

Topical Agents

High-potency topical corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment. Typically prescribed agents include fluocinonide, clobetasol propionate, and betamethasone dipropionate. Desquamative gingival lesions may be managed effectively with the application of gel-based topical corticosteroids to the lesion. Application may be facilitated by the placement of a resilient vacuum-formed occlusive splint that covers the involved gingiva ( Fig. 5 ).