http://evolve.elsevier.com/Haveles/pharmacology

Contemporary general anesthetic techniques use balanced anesthesia, which employs a combination of drugs to produce a reversible loss of consciousness and insensibility to painful stimuli while minimizing adverse reactions, taking into account the patient’s physical status and preanesthetic and postanesthetic needs.

In oral health care, oral and maxillofacial surgeons use general anesthetic drugs in their offices. General dentists use nitrous oxide to provide conscious sedation and pain control. Although dental hygienists are not generally involved with the administration of general anesthesia, many states allow them to monitor and/or administer nitrous oxide for conscious sedation. In today’s practice, the dental hygienist should have an understanding of the principles of general anesthesia because it is an indispensable tool used to meet the needs of special patients and for extensive oral and maxillofacial surgery.

History

The original methods of producing general anesthesia involved either strangulation or cerebral concussion. Later, opium, belladonna, hemp, and alcohol were used to render patients unconscious. During this time, the operations were “quick and dirty.” Nitrous oxide was discovered in 1776, and 20 years later Sir Humphrey Davy suggested that the administration of nitrous oxide might be useful in surgery. About the middle of the 1800s, true general anesthetics were discovered in the United States. In 1846 surgically related mortality dropped dramatically with the introduction of ether. Today, anesthesiologists use a combination of inhaled and intravenous general anesthetics and adjuvant drugs to produce a generalized, reversible depression of the central nervous system (CNS) that results in a loss of consciousness, amnesia, and immobility but not necessarily complete analgesia.

Mechanism of action

Overview

Many theories have been proposed to explain the mechanism of action of the various general anesthetic agents, but unfortunately no theory does so completely. It may seem relatively simple to say that these drugs are CNS depressants. However, the way in which they depress the normal functions of the CNS is complicated by the lack of knowledge of the physiologic and biochemical events of arousal and unconsciousness. Proposed mechanisms for the action of different general anesthetics involve an increase in the threshold for firing, facilitation of inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and a decrease in the duration of opening of nicotinic receptor-activated cation channels. The increase in the threshold or hyperpolarization is a result of the activation of the potassium channels.

Stages and Planes of Anesthesia

The extent of CNS depression produced by general anesthetics must be carefully titrated to avoid excessive cardiorespiratory depression. In 1920, Guedel described a system of stages and planes to describe the effects of anesthetics (Table 10-1). Although Guedel’s classification applied to the effects produced by ether during the open drop method of administration, modern anesthetic techniques seldom show these exact stages. However, the four stages are briefly described here because Guedel’s terminology is still used to describe the depth of anesthesia.

Table 10-1

Stages and Planes of Anesthesia

| Stage and Plane | Patient Response |

| Stage I: Analgesia | Patient is unresponsive Reduced sensation to pain Can still respond to commands Reflexes are present Regular respiration Some amnesia Loss of consciousness (end of stage) |

| Stage II: Delirium or excitement | Unconsciousness Amnesia Involuntary movement and excitement Irregular respiration Increased muscle tone Sympathetic stimulation: tachycardia, mydriasis, hypertension |

| Stage III: Surgical anesthesia | Return to regular respiration, muscle relaxation, and normal heart and pulse rates Divided into four planes |

| Stage IV: Respiratory or medullary paralysis | Cessation of respiration Subsequent circulatory failure Respiration must be artificially maintained |

Copyright 1996 Elena Bablenis Haveles.

Induction is the term used to refer to the quick change in the patient’s state of consciousness from stage I to stage III, as follows:

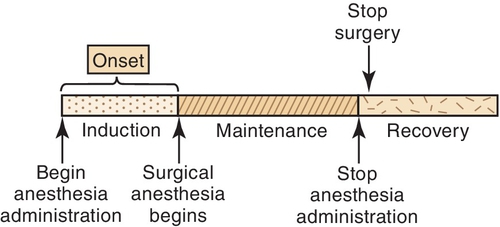

Modern anesthetic techniques now use more rapidly acting agents than those associated with the four stages described by Guedel. Flagg’s approach, used to describe the levels of anesthesia (Figure 10-1), uses the following categories:

Adverse reactions

The goals of surgical anesthesia are good patient control, adequate muscle relaxation, and pain relief. To produce anesthesia, potent CNS depressants are given in relatively high doses, and many combinations of drugs are used in balanced anesthesia. The hazards encountered with the administration of general anesthetics are summarized in Table 10-2.

Table 10-2

Adverse Reactions to General Anesthetics

| System | Effect/Comment* |

| Cardiovascular system | Cardiovascular collapse Cardiac arrest |

| Arrhythmias | Ventricular fibrillation with halogenated hydrocarbons |

| Blood pressure | Hypertension (stage II) Hypotension |

| Respiration | Depressed respiration (stage III) Respiratory arrest (stage IV) Laryngospasm with ultrashort-acting barbiturates “Boardlike” chest with neuroleptanalgesia |

| Explosions/flammability | Cyclopropane Ether |

| Teratogenicity (either male or female exposure) | Chronic exposure fetal abnormalities Spontaneous abortions |

| Hepatotoxicity (repeated exposure) | Operating room personnel Halogenated hydrocarbons |

| Other | Headache, fatigue, irritability, addicting |

* Stage refers to Guedel’s stage of anesthesia.

General anesthetics

Classification of Anesthetic Agents

The general anesthetic agents can be classified according to their chemical structures or routes of administration. Table 10-3 categorizes the agents according to their routes of administration.

Induction Anesthesia

Intravenous Anesthetics

The intravenously administered general anesthetics are a diverse group of CNS depressants that include the opioids, the ultrashort-acting barbiturates, and the benzodiazepines. Although most injectable general anesthetics are administered intravenously, one agent, ketamine, can also be given intramuscularly. These drugs find their greatest utility in induction of general anesthesia but may occasionally be used as single agents for short procedures. Although they offer the advantage of convenience, the depth and duration of anesthesia are less easily controlled with them than with the inhalation agents.

Ultrashort-Acting Barbiturates

The ultrashort-acting barbiturates used include methohexital (meth-oh-HEX-i-tal) sodium (Brevital), thiopental (thye-oh-PEN-tal) sodium (Pentothal), and thiamylal (thye-AM-i-lal) sodium (Surital). These ultrashort-acting agents have a rapid onset of action (about 30-40 seconds) when given intravenously. They are highly lipid soluble, and repeated dosing during anesthesia can result in a prolonged recovery period. However, blood and brain levels of these agents quickly decrease as the drugs redistribute to lean tissues (skeletal muscle).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses