The rate of technological change in contemporary society is accelerating, and orthodontics is not exempt from this process. After a century of inconclusive evidence, the question of whether craniofacial growth can be modified by functional orthopedic techniques remains unresolved. A new paradigm for successful treatment presents a philosophical challenge: to combine the benefits of orthodontic and orthopedic techniques in the treatment of malocclusions that require a combination of dental and skeletal correction.

ORTHODONTICS AND DENTOFACIAL ORTHOPEDICS

What ambitions do orthodontists hold for the future? As implied by the definition of “orthodontics,” are they satisfied simply to produce “straight teeth” within the strict confines of a genetic paradigm? Is there a scope for significant improvements in conventional orthodontic techniques, or has this aspect of orthodontic development been exhausted? Precision orthodontic techniques with conventional fixed appliances have simplified orthodontic correction and are frequently delegated to auxiliaries under supervision. If treatment objectives are confined to orthodontics, will specialists still be needed?

An essential distinction exists between the terms orthodontics and dental orthopedics, which vary fundamentally in their approach to the correction of dentofacial abnormalities. By definition, “orthodontic” treatment aims to correct dental irregularity. The alternative term “dental orthopaedics” was suggested by the late Sir Norman Bennett, and although it has a wider definition than “orthodontics,” it still does not convey the objective of improving facial development. The broader description of dentofacial orthopedics conveys the concept that treatment aims to improve not only dental and orthopedic relationships in the stomatognathic system, but also facial balance. The adoption of a wider definition has the advantage of extending the horizons of the profession, as well as educating the public to appreciate the benefits of dentofacial therapy in more comprehensive esthetic terms.

Abnormal musculoskeletal development is frequently the cause of dental malocclusion. The treatment objective in the growing child with a resultant skeletal discrepancy changes from an orthodontic approach, aiming to correct the dental irregularity, to an orthopedic approach, where the objective is to correct the underlying skeletal abnormality. This difference in emphasis reflects the existence of two distinct schools of thought in evaluating the aims of orthodontic and dental orthopedic treatment.

After a century of investigating functional orthopedic techniques, opinions still vary regarding their effectiveness in promoting or modifying dentofacial growth and development. In the evolution of orthodontic technique, geographical location has been a significant factor. Functional orthopedic techniques were developed mainly in Europe during the twentieth century, and in the past, Europeans had greater experience with these techniques than their colleagues around the world. In many countries, fixed-appliance techniques have been the basis of orthodontic training programs, often with limited exposure to the teachings and practice of orthopedics, depending on the prevailing philosophy of treatment.

The orthopedic response to functional therapy has frequently been questioned on the basis of results published in the literature. The majority of studies during the twentieth century relate to part-time wear of functional appliances. Inevitably, there is a time lag between the development of new clinical techniques and their acceptance by scientific investigation. Evidence-based research largely depends on statistical analysis of existing techniques and does not take into account future developments. However, this should not limit the ability to explore new horizons in orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics.

Significantly, the title of the American Journal of Orthodontics was revised in 1985 to include dentofacial orthopedics. Its current title is the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics (AJODO). The American Dental Association (ADA) adopted the new name and definition for the specialty of “orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics” in April 2003. These visionary changes can be attributed mainly to the efforts of Thomas M. Graber (mentor and former editor of AJODO) in recognizing the importance of dentofacial orthopedics as a means of correcting musculoskeletal discrepancies by functional orthopedic techniques. This represents the first official recognition within the specialty, and in the dental profession as a whole, of the importance of orthopedics in the field of orthodontics.

CONCEPT OF FUNCTIONAL THERAPY

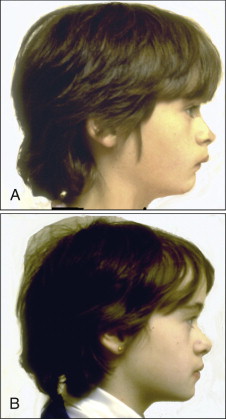

The challenge of functional therapy is to maximize the genetic potential of growth of the individual and guide the growing face and developing dentition toward a pattern of optimal development ( Fig. 9-1 ).

Review of Treatment Objectives

New research is providing convincing evidence to support the value of orthopedic techniques using full-time appliances to influence the functional environment of the developing dentition and to produce significant improvements in the pattern of facial growth and dental arch development.

The new challenge in the specialty is to improve orthopedic techniques in the treatment of skeletal and functional discrepancies and to relate this treatment to the holistic functional treatment objectives. It is essential to recognize the importance of using orthopedic techniques to achieve facial balance and harmony and to extend esthetic and functional objectives beyond a balanced functional occlusion.

Distraction osteogenesis illustrates the potential for modifying bone growth, and fixed functional techniques offer a new opportunity for noninvasive, osteogenic stimulation.

The next step in the evolution of orthopedic techniques is to resolve any remaining doubts regarding the efficacy of an orthopedic approach and to improve techniques in order to combine the benefits of orthodontic and orthopedic treatment.

Recent Research in Growth Modification

Do functional appliances produce supplementary growth of the mandible? This question has remained unanswered throughout the last century.

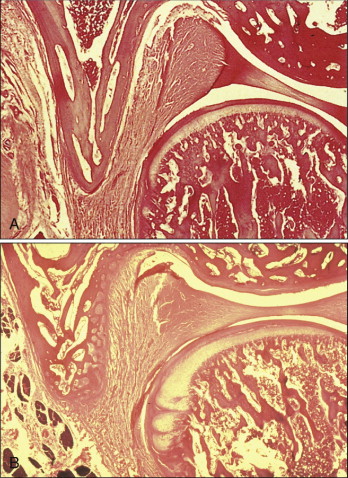

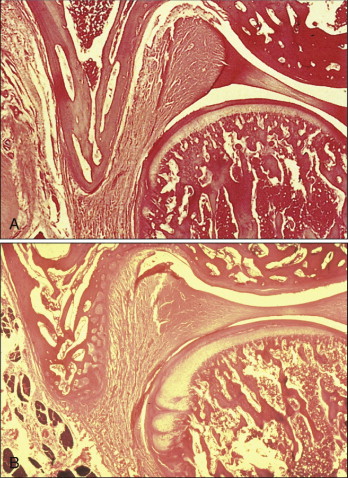

Remodeling of the condyle and the fossa in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) was originally investigated in animal experiments ( Fig. 9-2 ). The potential for condylar growth and new bone formation in the glenoid fossa to change growth of the fossa to an anterior direction is now established in nonhuman primates. Anterior and inferior remodeling of the glenoid fossa was seen in a reverse direction compared with controls. A study of juvenile Macaca fascicularis monkeys with Herbst treatment concluded the following:

- •

Increased condylar growth can be demonstrated cephalometrically with the Björk implant method and confirmed histologically.

- •

“The potential for condylar growth in juvenile non primates in the mixed dentition to induce increased mandibular length appears to be great.”

- •

Histomorphometric analysis shows that the increased amount and area of new bone in the glenoid fossa are statistically significant compared with controls. This formation appears to increase with time.

Clinical Studies

Parallel clinical studies with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have since confirmed, first in Herbst treatment and later in twin block therapy, that similar clinical growth changes occur in response to mandibular propulsion with full-time functional appliances. Growth studies during and after twin block therapy compared matched controls from the Burlington Growth Centre and concluded the following :

- •

Mandibular unit length increases almost three times as much in twin block patients as in controls.

- •

Approximately two thirds of the increase can be attributed to an increase in mandibular ramus height.

- •

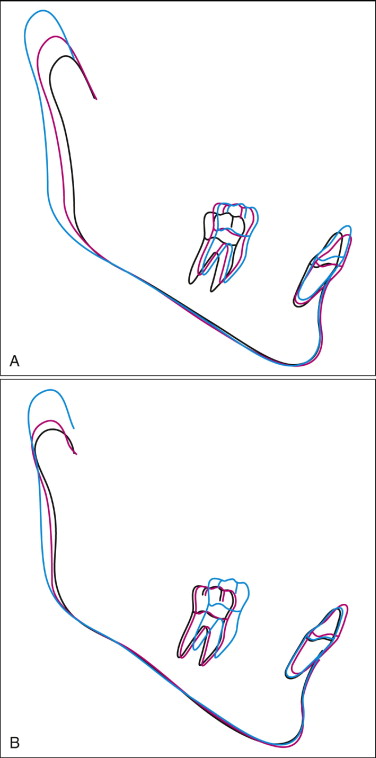

Much of the skeletal improvement is related to an increase in mandibular length, and these changes largely are stable 3 years after treatment ( Fig. 9-3 ).

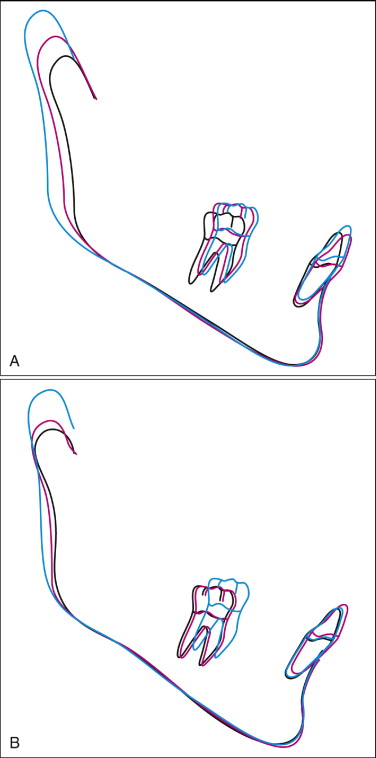

Fig. 9-3 A, Twin block treatment. B, Controls. Treatment: T 1 = 9 years, 1 month; T 2 = 10 years, 3 months; T 3 = 13 years, 1 month. Control: T 1 = 9 years, 1 month; T 2 = 10 years, 2 months; T 3 = 12 years, 11 months. This illustrates an important difference in response between twin block treatment and controls. In addition to extension of condylar length, the twin block sample clearly shows distal growth of the condyle compared to vertical growth in the controls. A change in direction of growth of the condyle contributes to forward positioning of the mandible in correction of mandibular retrusion.(From Clark WJ: Twin block functional therapy: applications in dentofacial orthopaedics, ed 2, Edinburgh, 2002, Mosby Ltd.)

An interesting pattern is observed in which the gonial angle frequently increases during the twin block stage of treatment, followed by an increase in corpus length during the posttreatment period. This may be interpreted as a change in condylar growth to a more distal direction during active mandibular propulsion, followed by remodeling of the mandibular ramus posttreatment to restore the original shape of the mandible.

This pattern of distal growth of the condyle is confirmed in a finite element scaling analysis to determine the localization of mandibular changes in patients treated by the author with the twin block appliance. In all four groups of prepubertal and postpubertal boys and girls, the distal area of the neck of the condyle showed the most significant growth changes. This may be interpreted as remodeling of the neck of the condyle as a result of lengthening or distal growth of the condyle.

A prospective study of twin block appliance therapy assessed by MRI in the University of Adelaide confirmed the following:

- •

Condyles that were positioned at the crest of the eminence at the beginning of treatment had reseated back into the glenoid fossa after 6 months.

The clinical implication of this finding is that active functional therapy by forward mandibular propulsion should continue for a minimum of 6 months or preferably 9 months. This ensures that treatment continues for a sufficient time to allow adaptive skeletal growth changes to occur, and that these changes are reinforced before the functional appliance is removed. In addition, the author advises that functional therapy should be followed by a period of functional retention, with the mandible supported in a forward position, perhaps with a nighttime functional appliance. This protocol is successful in preventing “mandibular setback,” which has been previously reported after functional treatment to advance the mandible.

Biological Research

Biological research is making rapid progress in identifying the controlling factors in growth modification. The landmark article “Functional appliance therapy accelerates and enhances condylar growth” is not the optimistic evaluation of an enthusiastic clinician. Rather, it represents a revolution in scientific research techniques at the cellular and molecular level to examine and define the chemical and biological factors involved in growth modification.

Replicating mesenchymal cells have been identified in the condyle and glenoid fossa during mandibular forward positioning. Scientific study confirms the importance of the genetic control factor. Patients with a high mesenchymal cell count would respond well to functional mandibular advancement, whereas a low cell count would produce a poor mandibular growth response.

In the future, the mesenchymal cell count from a blood sample may define a patient’s potential to respond to functional mandibular advancement. Clinicians may be able to predict the individual patient’s response to functional therapy with information from a blood test or salivary smear. Biological research can answer the questions that statistical studies have failed to resolve.

CONCEPT OF FUNCTIONAL THERAPY

The challenge of functional therapy is to maximize the genetic potential of growth of the individual and guide the growing face and developing dentition toward a pattern of optimal development ( Fig. 9-1 ).

Review of Treatment Objectives

New research is providing convincing evidence to support the value of orthopedic techniques using full-time appliances to influence the functional environment of the developing dentition and to produce significant improvements in the pattern of facial growth and dental arch development.

The new challenge in the specialty is to improve orthopedic techniques in the treatment of skeletal and functional discrepancies and to relate this treatment to the holistic functional treatment objectives. It is essential to recognize the importance of using orthopedic techniques to achieve facial balance and harmony and to extend esthetic and functional objectives beyond a balanced functional occlusion.

Distraction osteogenesis illustrates the potential for modifying bone growth, and fixed functional techniques offer a new opportunity for noninvasive, osteogenic stimulation.

The next step in the evolution of orthopedic techniques is to resolve any remaining doubts regarding the efficacy of an orthopedic approach and to improve techniques in order to combine the benefits of orthodontic and orthopedic treatment.

Recent Research in Growth Modification

Do functional appliances produce supplementary growth of the mandible? This question has remained unanswered throughout the last century.

Remodeling of the condyle and the fossa in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) was originally investigated in animal experiments ( Fig. 9-2 ). The potential for condylar growth and new bone formation in the glenoid fossa to change growth of the fossa to an anterior direction is now established in nonhuman primates. Anterior and inferior remodeling of the glenoid fossa was seen in a reverse direction compared with controls. A study of juvenile Macaca fascicularis monkeys with Herbst treatment concluded the following:

- •

Increased condylar growth can be demonstrated cephalometrically with the Björk implant method and confirmed histologically.

- •

“The potential for condylar growth in juvenile non primates in the mixed dentition to induce increased mandibular length appears to be great.”

- •

Histomorphometric analysis shows that the increased amount and area of new bone in the glenoid fossa are statistically significant compared with controls. This formation appears to increase with time.

Clinical Studies

Parallel clinical studies with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have since confirmed, first in Herbst treatment and later in twin block therapy, that similar clinical growth changes occur in response to mandibular propulsion with full-time functional appliances. Growth studies during and after twin block therapy compared matched controls from the Burlington Growth Centre and concluded the following :

- •

Mandibular unit length increases almost three times as much in twin block patients as in controls.

- •

Approximately two thirds of the increase can be attributed to an increase in mandibular ramus height.

- •

Much of the skeletal improvement is related to an increase in mandibular length, and these changes largely are stable 3 years after treatment ( Fig. 9-3 ).

Fig. 9-3 A, Twin block treatment. B, Controls. Treatment: T 1 = 9 years, 1 month; T 2 = 10 years, 3 months; T 3 = 13 years, 1 month. Control: T 1 = 9 years, 1 month; T 2 = 10 years, 2 months; T 3 = 12 years, 11 months. This illustrates an important difference in response between twin block treatment and controls. In addition to extension of condylar length, the twin block sample clearly shows distal growth of the condyle compared to vertical growth in the controls. A change in direction of growth of the condyle contributes to forward positioning of the mandible in correction of mandibular retrusion.(From Clark WJ: Twin block functional therapy: applications in dentofacial orthopaedics, ed 2, Edinburgh, 2002, Mosby Ltd.)

An interesting pattern is observed in which the gonial angle frequently increases during the twin block stage of treatment, followed by an increase in corpus length during the posttreatment period. This may be interpreted as a change in condylar growth to a more distal direction during active mandibular propulsion, followed by remodeling of the mandibular ramus posttreatment to restore the original shape of the mandible.

This pattern of distal growth of the condyle is confirmed in a finite element scaling analysis to determine the localization of mandibular changes in patients treated by the author with the twin block appliance. In all four groups of prepubertal and postpubertal boys and girls, the distal area of the neck of the condyle showed the most significant growth changes. This may be interpreted as remodeling of the neck of the condyle as a result of lengthening or distal growth of the condyle.

A prospective study of twin block appliance therapy assessed by MRI in the University of Adelaide confirmed the following:

- •

Condyles that were positioned at the crest of the eminence at the beginning of treatment had reseated back into the glenoid fossa after 6 months.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses