History of Distraction

The first clinical application of bone distraction was described in 1905 by Codivilla, who performed a bone distraction of the lower leg. The distractor was fixed with plaster at the upper and lower leg, providing only minor stability, and severe soft tissue problems such as necrosis occurred. Various experimental studies followed regarding the rate and distance of distraction and the effects of the periosteum and soft tissue on the distraction process. In 1927, Rosenthal reported the first distraction of the mandible. He treated a patient with a mandibular retrognathism by bone distraction and fixation of the distractor along the teeth. In 1952, Anderson used cortical bone pins for the fixation of the distractor, as described by Coleman et al. in 1967. This was a milestone in the technique of bone distraction because it enabled rigid fixation of the bone fragments.

The real father of bone distraction was a Russian orthopedic surgeon named Ilizarov, who popularized the technique more than 30 years before it became recognized in the West. In the late 1980s, he published in the United States for the first time his research and clinical results on bone distraction, prompting a wave of developments in bone distraction techniques worldwide.

Principle of Bone Distraction

The aim of bone distraction is to obtain new bone tissue and gain bone length by slow distraction of the callus. The basic principle of bone distraction is the process of bone fracture healing. Osteotomy can be performed by two methods. In the original method, as described by Ilizarov, a corticotomy is performed in which only the cortex of the bone is separated and the cancellus stays untouched. Another method, which is more often used in head and neck surgery, is to split the cortex and the cancellus of the bone to facilitate the process of distraction. With this technique, the forces needed to distract the bone are significantly lower, allowing use of smaller distractors that can be placed under the skin or the mucosa.

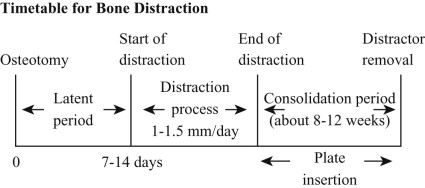

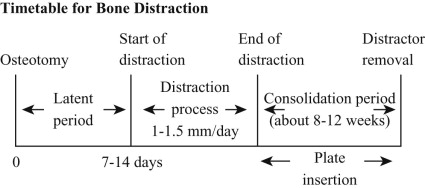

After the osteotomy and a latent period of 5 to 7 days, the bones on both sides of the osteotomy line are slowly pulled apart to stretch the fracture cleft and the newly formed callus. A latent period between the osteotomy and the start of the distraction process allows callus formation and soft tissue healing. Higher activity of the osteoblasts and blood vessel growth within the osteotomy line and the callus can be achieved. Various experimental and clinical studies have reported a latent period ranging from 0 to 14 days between the osteotomy and the start of the distraction, depending on the individual situation. In the field of head and neck surgery, an average waiting period of 5 to 7 days is advisable. However, patient age, bone size, and soft tissue coverage may influence the latent period.

Distraction must take place slowly to achieve new bone formation within the callus. An average distraction rate of 1 to 1.5 mm/day provides the best clinical results. At a lower rate of 0.5 mm/day or less, early ossification takes place, whereas at a higher rate of 2 mm/day or more, no bone formation occurs. Another important fact is the frequency of distraction. The ideal situation is a continuous distraction of callus, but because this is difficult, repeated distraction once or twice each day (1-1.5 mm/day total) seems to be useful.

Numerous experimental and clinical studies have investigated the effects of bone distraction and the progress of bone formation during distraction. It has been shown that the gap between the distracted bone edges is first occupied by fibrous tissue. As distraction proceeds, the fibrous tissue becomes longitudinally oriented in the direction of distraction. Early bone formation starts from the cut bone edges and advances along the fibrous tissue. Bone is formed predominantly by intermembranous ossification. Histological observations showed a gradual change from an amorphous matrix to a fibrous matrix and then to an osseous-like tissue. Bone columns crystallize along longitudinally oriented collagen bundles, expanding circumferentially to surrounding bundles. While the distraction gap increases, the bone columns increase in length and diameter, whereas the fibrous interzone remains constant at a few millimeters. Clinical and animal experimental data have shown that distraction osteogenesis provides unlimited new bone formation that remodels at a daily rate ranging from 200 to 400 μm. Most of the experimental data were obtained from orthopedic studies, and only limited information about the indications for maxillofacial surgery is available.

Various methods have been described for fixation of the distractor. The easiest method of fixation is to use bone pins that are placed in the bone near the osteotomy line and through the skin. The pins are fixed externally to the distractor, which can be slowly expanded. The external distractors are easy to fix and very stable, but most of them are rather bulky, and the transcutaneous pins can cause scars. These factors encouraged the development of smaller devices that can be placed intraorally. Today, minidistractors and microdistractors are currently used; they are small enough to be placed completely subcutaneously or under the mucosa. Only the screw for the activator of the distractor is visible.

Another distractor for the midface is the halo frame. The frame is fixed at the skull by screws and attached to the midface.

An important aspect of all distractors is their stability and stiffness. Experimental studies have shown that mobility during the process of distraction can cause micromovements, resulting in impaired bone formation. Distractor size is therefore limited by physical stability and rigidity.

After reaching the intended bone length, the distractor (or plate fixation) must stay in place for many weeks until mineralization and ossification of the newly formed callus has been completed and sufficient bone strength has been attained. The length of this period depends on individual factors such as the location of the osteotomy, the bone length gained, and the age of the patient. A retention period of 8 to 12 weeks seems to be sufficient for the facial skeleton. Some surgeons remove the distractor and use plates to provide stabilization for the consolidation period.

Principle of Bone Distraction

The aim of bone distraction is to obtain new bone tissue and gain bone length by slow distraction of the callus. The basic principle of bone distraction is the process of bone fracture healing. Osteotomy can be performed by two methods. In the original method, as described by Ilizarov, a corticotomy is performed in which only the cortex of the bone is separated and the cancellus stays untouched. Another method, which is more often used in head and neck surgery, is to split the cortex and the cancellus of the bone to facilitate the process of distraction. With this technique, the forces needed to distract the bone are significantly lower, allowing use of smaller distractors that can be placed under the skin or the mucosa.

After the osteotomy and a latent period of 5 to 7 days, the bones on both sides of the osteotomy line are slowly pulled apart to stretch the fracture cleft and the newly formed callus. A latent period between the osteotomy and the start of the distraction process allows callus formation and soft tissue healing. Higher activity of the osteoblasts and blood vessel growth within the osteotomy line and the callus can be achieved. Various experimental and clinical studies have reported a latent period ranging from 0 to 14 days between the osteotomy and the start of the distraction, depending on the individual situation. In the field of head and neck surgery, an average waiting period of 5 to 7 days is advisable. However, patient age, bone size, and soft tissue coverage may influence the latent period.

Distraction must take place slowly to achieve new bone formation within the callus. An average distraction rate of 1 to 1.5 mm/day provides the best clinical results. At a lower rate of 0.5 mm/day or less, early ossification takes place, whereas at a higher rate of 2 mm/day or more, no bone formation occurs. Another important fact is the frequency of distraction. The ideal situation is a continuous distraction of callus, but because this is difficult, repeated distraction once or twice each day (1-1.5 mm/day total) seems to be useful.

Numerous experimental and clinical studies have investigated the effects of bone distraction and the progress of bone formation during distraction. It has been shown that the gap between the distracted bone edges is first occupied by fibrous tissue. As distraction proceeds, the fibrous tissue becomes longitudinally oriented in the direction of distraction. Early bone formation starts from the cut bone edges and advances along the fibrous tissue. Bone is formed predominantly by intermembranous ossification. Histological observations showed a gradual change from an amorphous matrix to a fibrous matrix and then to an osseous-like tissue. Bone columns crystallize along longitudinally oriented collagen bundles, expanding circumferentially to surrounding bundles. While the distraction gap increases, the bone columns increase in length and diameter, whereas the fibrous interzone remains constant at a few millimeters. Clinical and animal experimental data have shown that distraction osteogenesis provides unlimited new bone formation that remodels at a daily rate ranging from 200 to 400 μm. Most of the experimental data were obtained from orthopedic studies, and only limited information about the indications for maxillofacial surgery is available.

Various methods have been described for fixation of the distractor. The easiest method of fixation is to use bone pins that are placed in the bone near the osteotomy line and through the skin. The pins are fixed externally to the distractor, which can be slowly expanded. The external distractors are easy to fix and very stable, but most of them are rather bulky, and the transcutaneous pins can cause scars. These factors encouraged the development of smaller devices that can be placed intraorally. Today, minidistractors and microdistractors are currently used; they are small enough to be placed completely subcutaneously or under the mucosa. Only the screw for the activator of the distractor is visible.

Another distractor for the midface is the halo frame. The frame is fixed at the skull by screws and attached to the midface.

An important aspect of all distractors is their stability and stiffness. Experimental studies have shown that mobility during the process of distraction can cause micromovements, resulting in impaired bone formation. Distractor size is therefore limited by physical stability and rigidity.

After reaching the intended bone length, the distractor (or plate fixation) must stay in place for many weeks until mineralization and ossification of the newly formed callus has been completed and sufficient bone strength has been attained. The length of this period depends on individual factors such as the location of the osteotomy, the bone length gained, and the age of the patient. A retention period of 8 to 12 weeks seems to be sufficient for the facial skeleton. Some surgeons remove the distractor and use plates to provide stabilization for the consolidation period.

Indications and Techniques for Bone Distraction

Congenital malformations of the mandible originally were the most common indications for distraction. McCarthy et al. first described the use of a miniaturized distractor as an extraoral device to lengthen the malformed mandible. Soon, smaller distractors were developed that were placed completely intraorally to avoid scars and hide the distractors. Currently, distraction of the mandible can be classified as distraction of the horizontal mandible ramus, the vertical mandible ramus, the mandible symphysis, or the alveolus.

Horizontal or Vertical Distraction of the Ramus or Angle of the Mandible

Malformations of ramus growth horizontally or vertically are the most common indications for distraction in the field of head and neck surgery. In less severe orthognathic surgery cases, a unilateral or bilateral sagittal split can be performed, followed by bone distraction until the intended occlusion is reached. With osteotomies of the cortex alone, the risk of nerve injury is less likely. This approach also may have a role in cases of severe trauma.

Other indications include congenital, traumatic, or infection-induced hypoplasia of the mandible in young children ( Figs. 25-1 through 25-3 ) if functional orthopedics does not work and the airway is impaired. With distraction of the mandible, the space for soft tissues such as the tongue and the floor of the mouth increases, improving airflow. This application can avoid a permanent tracheotomy, and it can be used from the age of 6 months, when ossification of the mandible allows fixation of the distractor.

The part of the mandible that must be distracted depends on the location of the bone growth deficit. Because some distractors have only one vector of distraction, the bone must be advanced in one direction, and the position of the distractor is critical for the final clinical result. The placement of the distractor parallel to the occlusal plane results in horizontal mandibular advancement. If the distractor is placed at an angle to the occlusion plane, the results are mandibular advancement and a tendency for an open bite. A distractor set vertically in relation to the occlusion plane produces malocclusion of the molars. The position and angle between the distractor and the occlusal plane must be determined carefully preoperatively by a cephalometric analysis or model surgery, or both. In some cases, bilateral osteotomy and distraction may be necessary.

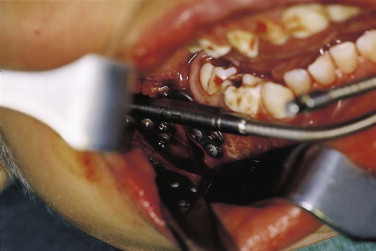

The operation is usually performed with the patient under general anesthesia. After local disinfection and injection of a vasoconstrictor, the mucosa is opened, and the mandible is exposed subperiosteally. The distractor is placed at the intended position and fixed temporarily with two monocortical screws. The osteotomy line is marked on the buccal side of the mandible using a drill. The distractor and the screws are removed, and the osteotomy is performed. The lingual side of the osteotomy is performed carefully to prevent exposure of the lingual periosteum, which is important for the blood supply. The bone is mobilized, and the distractor is fixed using the holes drilled earlier and the remaining screws. The soft tissue is closed so that the thread of the distractor is visible and can easily be reached by the patient. After a waiting period of about 5 to 7 days, distraction can be started at a rate of 0.5 mm twice daily until the intended mandible length is obtained.

The retention period lasts about 12 weeks before the distractor can be removed under local or general anesthesia. Some surgeons replace the distractor with plates to complement the consolidation period.

Distraction of the Mandibular Symphysis

In patients with a congenital or trauma-induced narrow mandible (e.g., after mandible fracture), surgical widening may be necessary ( Figs. 25-4 through 25-6 ). Vertical osteotomy of the mandible between the incisors followed by horizontal distraction results in a significant increase in width. Because of the principle of distraction, the condyles are rotated, but this causes no permanent problems.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses