Deep overbite is perhaps one of the most common malocclusion and the most difficult to treat successfully. The amount of incisor overlap varies greatly and is primarily a manifestation of dental malocclusion. Understanding the concept of overbite is imperative to any discussion of deep-bite malocclusion. In 1950, Strang defined overbite as “the overlapping of the upper anterior teeth over the lowers in the vertical plane.” However, the crown length of the upper and lower incisors varies significantly in individuals. Therefore a definition of overbite that includes “percentage” is more descriptive and useful: hence it would be more appropriate to redefine overbite as “the amount and percentage of overlap of the lower incisors by the upper incisors.”

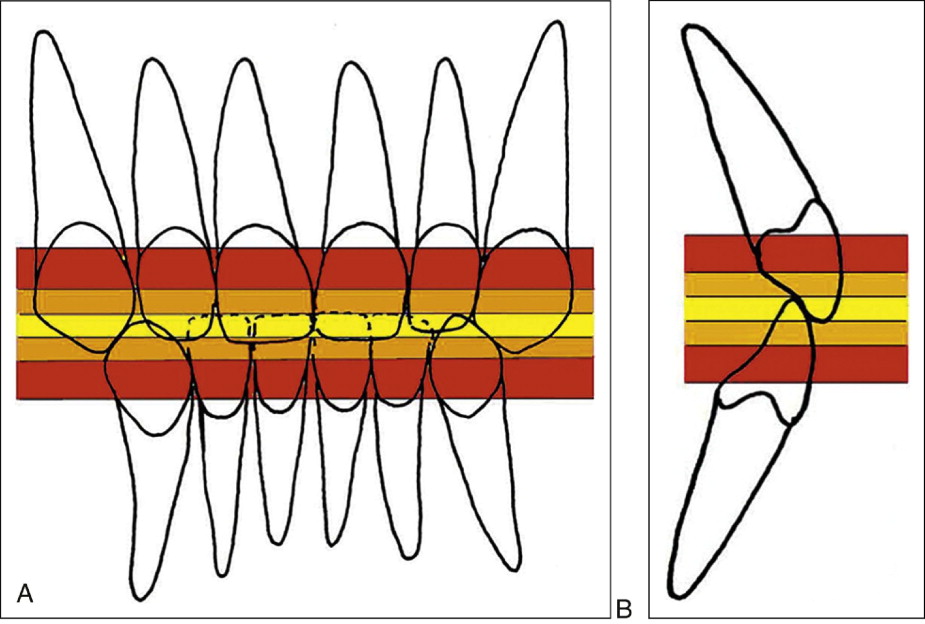

The ideal overbite in a normal occlusion may range from 2 to 4 mm, or more appropriately, 5% to 25% (overlap of mandibular incisors by maxillary incisors) ( Fig. 16-1 ). According to Nanda, a range of 25% to 40% without associated functional problems during various movements of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) may be considered “normal.” However, overlap greater than 40% should be considered “excessive” (deep bite) because of the potential for deleterious effects on the overall health of the surrounding periodontal structures and the TMJ. At 5 to 6 years of age the percentage of overbite varies between 36.5% and 39.2%. From 9 to 12 years of age the overbite usually increases, whereas it decreases at 12 years to adulthood. Thereafter, overbite remains largely unchanged, varying between 37.9% and 40.7%, unless affected by other factors, such as abrasion or loss of teeth, which can potentially reduce vertical dimension.

A severe expression of excessive overbite is the cover bite ( Fig. 16-2, A-C ). Cover bite is associated primarily with the Class II, Division 2 malocclusion. This condition was first recorded in 1912 in the German literature as Deckbiss. Cover bite is characterized by complete covering (concealment) of the mandibular incisor crowns resulting from excessive overbite and retroclination of the maxillary incisors. Another term used to denote a severe form of deep bite is closed bite ( Fig. 16-2, D-F ). Closed bite is mainly seen in adults and rarely in young children and is characterized by excessive overbite resulting from loss of posterior teeth.

ETIOLOGY

Developmentally, a skeletal or dental overbite is caused by genetic or environmental factors, or a combination of both. Skeletal deep bites usually have a horizontal growth pattern and are characterized by (1) growth discrepancy of the maxillary and mandibular jawbones, (2) convergent rotation of the jaw bases, and/or (3) deficient mandibular ramus height. In these patients the anterior facial height is often short, particularly the lower facial third. On the other hand, dental deep bites show supraocclusion (overeruption) of the incisors, infraocclusion (undereruption) of the molars, or a combination. Other factors that can affect deep bite are alterations in tooth morphology, premature loss of permanent teeth resulting in lingual collapse of the maxillary or mandibular anterior teeth, mesiodistal width of anterior teeth, and natural, age-related deepening of the bite.

Deep bites that are primarily caused by environmental factors can also be classified as acquired deep bites. It is well known that a dynamic equilibrium exists between the structures around the teeth (tongue; buccinator, mentalis, and orbicularis oris muscles) and the occlusal forces, which assist in the balanced development and maintenance of the occlusion. Any environmental condition that disrupts this dynamic harmony can lead to a malocclusion, such as the following:

- •

A lateral tongue thrust or abnormal tongue posture causing infraocclusion of the posterior teeth

- •

Wearing away of the occlusal surface or tooth abrasion

- •

Anterior tipping of the posterior teeth into extraction sites

- •

Prolonged thumb sucking

Deep-bite etiology must be considered in detail to formulate a comprehensive diagnosis and treatment plan for each patient so that optimal skeletal, dental, and esthetic results can be attained.

DIAGNOSIS

A deep overbite can be corrected by extrusion of posterior teeth or by inhibition and genuine intrusion of anterior teeth, or by a combination ( Fig. 16-3 ). The choice of treatment is based in part on the etiology of deep bite, the amount of growth anticipated, the vertical dimension, relationship of the teeth with the adjoining soft tissue structures, and the desired position of the occlusal plane.

Growth Considerations

It is widely accepted that correction of deep bite is both easier to accomplish and more stable when performed on growing patients than when attempted on those with no appreciable growth remaining. Because growth tends to increase the vertical distance between maxilla and mandible, it is probably useful to treat such patients during a period of active mandibular growth. During the growth period, tooth eruption can be stimulated in posterior segments and inhibited in anterior segments because condylar growth allows for dentoalveolar growth.

In adults, however, such a movement is counteracted by the posterior occlusion, especially in those with a hypodivergent skeletal pattern. The stability of such tooth movement, if performed, is highly questionable because it leads to alterations in muscle physiology, increasing the risk of relapse. In these malocclusions and others in which growth stimulation is no longer possible, fixed or removable mechanical appliances are needed to achieve optimal treatment results. Some patients might require a surgical procedure. For example, in patients with vertical maxillary excess, a LeFort I osteotomy with maxillary impaction might be required to achieve optimum dentofacial esthetics. A detailed discussion on this subject is beyond the scope of this chapter and can be found elsewhere.

Assessment of the Vertical Dimension

Schudy advocated correction of deep bite with eruption of premolars and molars as the treatment of choice, whereas others have preferred intrusion of incisors for treating most of their patients. In addition to the above information, which is primarily anecdotal, it is important to carefully consider the influence of extrusive or intrusive mechanics on the vertical facial height of a patient, which in turn may affect the anteroposterior relationship of the maxilla and mandible.

In general, eruptive mechanics should not encroach on the “free-way space,” or interocclusal space, defined as the distance between the occlusal or incisal surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular teeth when the mandible is in the physiological rest position. The average interocclusal space is 2 to 4 mm. It is less for the posterior teeth and more for the anterior. When there is a larger-than-normal “free space,” greater opportunities exist for correction by guiding vertical alveolar development. For example, in a Class II, Division 2 patient with a hypodivergent facial pattern, redundant lips, and a flat mandibular plane angle, the deep bite can be corrected and facial esthetics improved by increasing the lower facial height or facial convexity. In most other Class II malocclusions, however, it is not always desirable to increase the vertical dimension, because it would tend to accentuate the point A–point B discrepancy and also increase an abnormally large lower face.

Soft Tissue Evaluation

Soft tissue relationships form an important diagnostic tool for deep-bite correction. The clinician should always consider the maxillary incisor position relative to the lip position to determine whether to maintain, intrude, or extrude the maxillary incisors relative to the upper lip. With the increased emphasis on smile esthetics and smile design, the use of “dynamic smile analysis” is supplementing static photographs in diagnosing malocclusions and formulating the appropriate treatment plan.

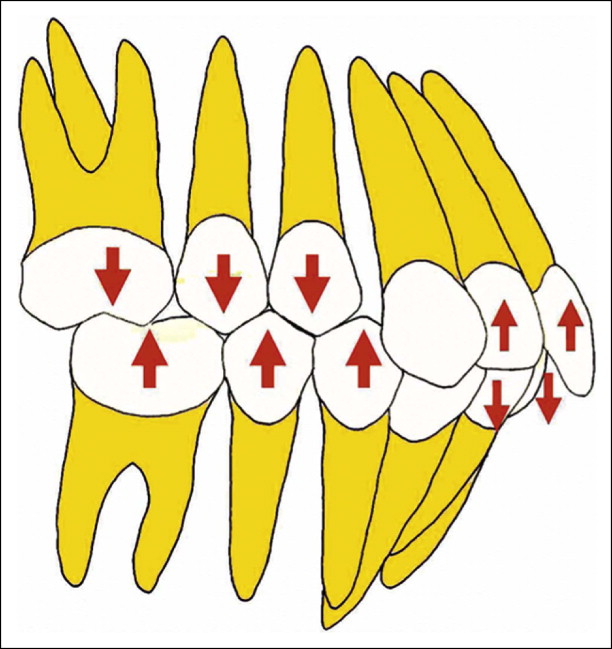

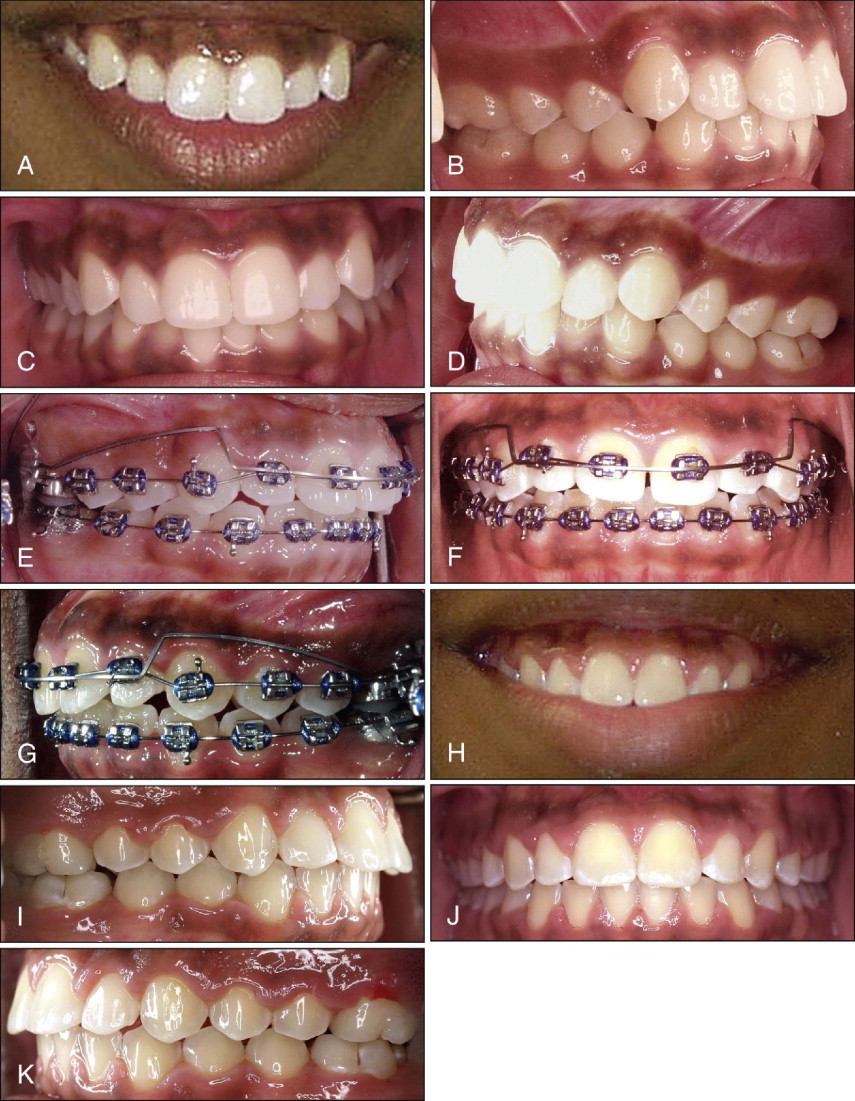

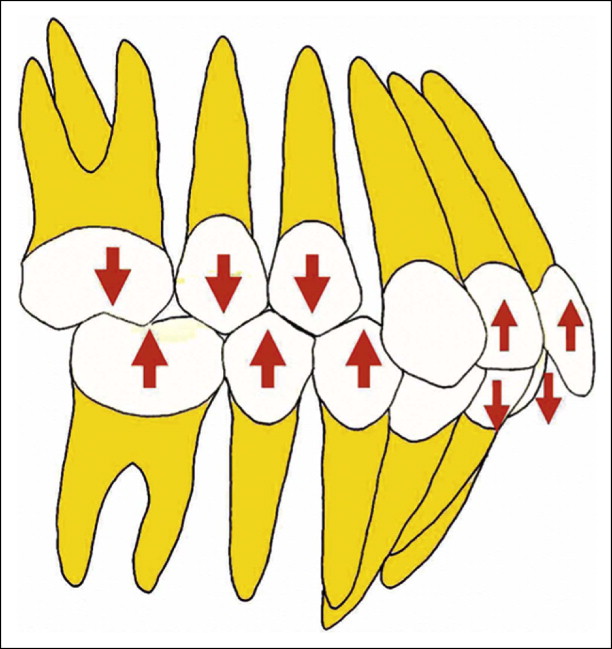

Incisal exposure should be considered in three different clinical situations during initial examination: in relaxed-lip position, while smiling, and during speech. In a relaxed-lip position, 2 to 4 mm of incisor exposure, which includes the incisal edges, is considered acceptable. When smiling, the average incisor exposure is almost two thirds of the upper incisor, according to Maulik and Nanda. They also report that in most “pleasing” smiles, the upper lip in men does not show gingiva, whereas women can have 1 to 2 mm of gingival exposure. If this condition is met and a deep bite is still present, the treatment plan should focus either on posterior extrusion (if the vertical parameters permit) or lower incisor intrusion ( Fig. 16-4 ). In contrast, an occlusal plane “significantly” below the ideal might show excessive gingiva and then require selective intrusion of the upper incisors ( Fig. 16-5 ). Incisor exposure during speech may also give additional information because different facial muscles are involved.

Another important factor to consider is the interlabial gap. In patients exhibiting large interlabial gap, performing posterior extrusive mechanics may be contraindicated because this could further worsen esthetics by increasing the interlabial gap. In fact, an increase in the interlabial gap may cause several other problems, such as inability to close the lips without strain and associated functional problems. However, in individuals with redundant upper and lower lips, or no interlabial gap, but who show excessive overbite, posterior extrusive mechanics may be indicated.

Flaring (proclining) the incisors is another option, which, however, primarily camouflages deep bites. Nonetheless it is useful in patients presenting with retroclined incisors (e.g., Class II, Division 2 cases) at the initial visit. However, rapid labial tipping of mandibular incisors must be avoided to minimize risk of root resorption, gingival recession, and bone dehiscence, especially on a narrow symphysis with questionable labiolingual width of the alveolar bone. Another contraindication may be undesirable facial esthetics.

DIAGNOSIS

A deep overbite can be corrected by extrusion of posterior teeth or by inhibition and genuine intrusion of anterior teeth, or by a combination ( Fig. 16-3 ). The choice of treatment is based in part on the etiology of deep bite, the amount of growth anticipated, the vertical dimension, relationship of the teeth with the adjoining soft tissue structures, and the desired position of the occlusal plane.

Growth Considerations

It is widely accepted that correction of deep bite is both easier to accomplish and more stable when performed on growing patients than when attempted on those with no appreciable growth remaining. Because growth tends to increase the vertical distance between maxilla and mandible, it is probably useful to treat such patients during a period of active mandibular growth. During the growth period, tooth eruption can be stimulated in posterior segments and inhibited in anterior segments because condylar growth allows for dentoalveolar growth.

In adults, however, such a movement is counteracted by the posterior occlusion, especially in those with a hypodivergent skeletal pattern. The stability of such tooth movement, if performed, is highly questionable because it leads to alterations in muscle physiology, increasing the risk of relapse. In these malocclusions and others in which growth stimulation is no longer possible, fixed or removable mechanical appliances are needed to achieve optimal treatment results. Some patients might require a surgical procedure. For example, in patients with vertical maxillary excess, a LeFort I osteotomy with maxillary impaction might be required to achieve optimum dentofacial esthetics. A detailed discussion on this subject is beyond the scope of this chapter and can be found elsewhere.

Assessment of the Vertical Dimension

Schudy advocated correction of deep bite with eruption of premolars and molars as the treatment of choice, whereas others have preferred intrusion of incisors for treating most of their patients. In addition to the above information, which is primarily anecdotal, it is important to carefully consider the influence of extrusive or intrusive mechanics on the vertical facial height of a patient, which in turn may affect the anteroposterior relationship of the maxilla and mandible.

In general, eruptive mechanics should not encroach on the “free-way space,” or interocclusal space, defined as the distance between the occlusal or incisal surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular teeth when the mandible is in the physiological rest position. The average interocclusal space is 2 to 4 mm. It is less for the posterior teeth and more for the anterior. When there is a larger-than-normal “free space,” greater opportunities exist for correction by guiding vertical alveolar development. For example, in a Class II, Division 2 patient with a hypodivergent facial pattern, redundant lips, and a flat mandibular plane angle, the deep bite can be corrected and facial esthetics improved by increasing the lower facial height or facial convexity. In most other Class II malocclusions, however, it is not always desirable to increase the vertical dimension, because it would tend to accentuate the point A–point B discrepancy and also increase an abnormally large lower face.

Soft Tissue Evaluation

Soft tissue relationships form an important diagnostic tool for deep-bite correction. The clinician should always consider the maxillary incisor position relative to the lip position to determine whether to maintain, intrude, or extrude the maxillary incisors relative to the upper lip. With the increased emphasis on smile esthetics and smile design, the use of “dynamic smile analysis” is supplementing static photographs in diagnosing malocclusions and formulating the appropriate treatment plan.

Incisal exposure should be considered in three different clinical situations during initial examination: in relaxed-lip position, while smiling, and during speech. In a relaxed-lip position, 2 to 4 mm of incisor exposure, which includes the incisal edges, is considered acceptable. When smiling, the average incisor exposure is almost two thirds of the upper incisor, according to Maulik and Nanda. They also report that in most “pleasing” smiles, the upper lip in men does not show gingiva, whereas women can have 1 to 2 mm of gingival exposure. If this condition is met and a deep bite is still present, the treatment plan should focus either on posterior extrusion (if the vertical parameters permit) or lower incisor intrusion ( Fig. 16-4 ). In contrast, an occlusal plane “significantly” below the ideal might show excessive gingiva and then require selective intrusion of the upper incisors ( Fig. 16-5 ). Incisor exposure during speech may also give additional information because different facial muscles are involved.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses