Although it is well established that people who have not satisfied their basic physiologic needs are not likely to be interested in much else, the relative order of some of the other needs may vary from person to person. Also, several different needs may motivate behavior at any given time.25

Physical and physiologic influences

Facial appearance

A study in 1921 highlighted the importance of facial appearance by proposing that the physical characteristics of individuals exert a profound influence over their associates.26 However, researchers did not quickly adopt this concept. Some speculate that our society’s emphasis on egalitarianism may have contributed to this omission. In other words, the belief that a person’s appearance ought not to make a difference in opportunities for development and success may have produced an “ostrich effect.”27

It was not until the 1960s that studies of facial appearance began appearing in the literature. In the 1970s research on the social psychology of facial appearance became more frequent. Although a vast number of studies have been reported, the quality of most of these studies is questionable.28 However, a growing body of information is now accumulating on facial appearance. Facial attractiveness has an important impact on an individual’s life, a fact increasingly recognized by dentists and physicians.29

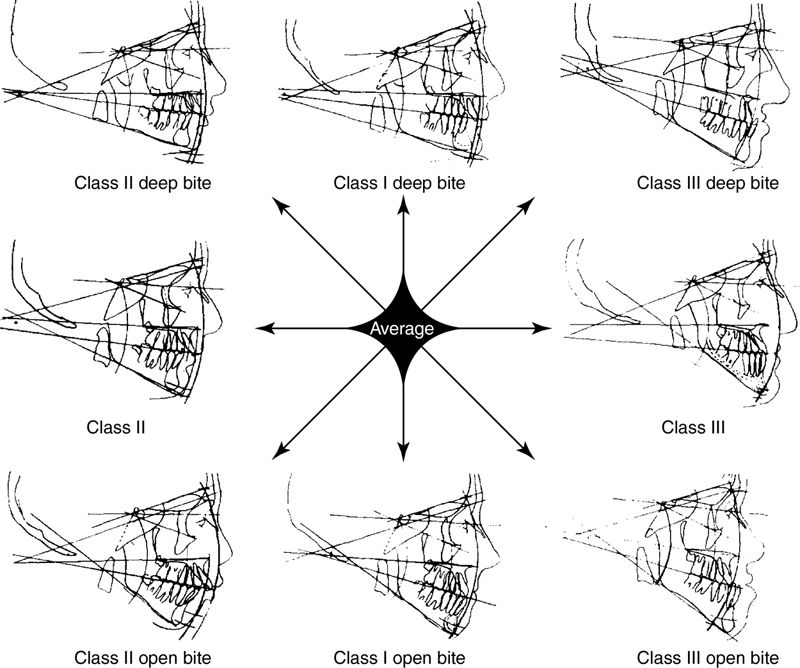

Few studies of facial appearance have investigated in a scientific manner those dimensions of the face and teeth that are responsible for a pleasant or an unpleasant face. In general, individuals in our society tend to reject the open bite facial types (either Class II or Class III) but more readily accept the deep bite facial type (Fig. 28-2).30,31

Regardless of the results of studies relating facial attractiveness to success in academics, careers, or interpersonal relationships, the personal testimonies of patients suggest that improved appearance is a goal worth pursuing, as the following situation clearly demonstrates.

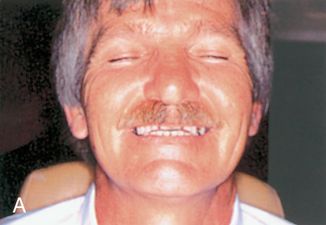

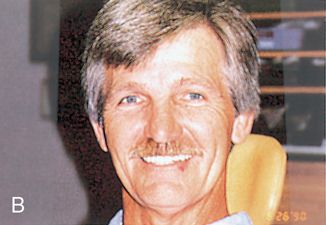

The patient is a 49-year-old real estate agent. He originally presented with a dour, morose appearance and was somewhat argumentative. Over the years he had abraded his teeth through bruxism until they were no longer visible when he talked or smiled. Eating was no longer enjoyable because of the significant loss of vertical occluding dimension, which led to facial distortion when he chewed. He was embarrassed by his image. He hoped for a “quick fix” to his problem.

A provisional diagnostic acrylic splint was placed to determine his tolerance for a restored vertical occlusion. The attractive splint dramatically changed his appearance. Composite resin veneers further enhanced the esthetics (Fig. 28- 3).

Over the next few weeks the patient’s personality gradually changed. He began to smile and appeared more relaxed. When questioned about this perceived change, he stated, “You’re absolutely right. You can’t believe how good I feel inside. I want to smile at everybody. I can’t pass a mirror without stopping to look at my new teeth. I can hardly wait to get my permanent restorations. Already I’ve started on a self-improvement program, losing a few pounds and toning up. Business has become a pleasure, and I feel more confident in social situations.”

The mouth and oral cavity

The mouth has long played a prominent role in psychologic theories (e.g., Freud incorporated the “oral” stage of development into psychoanalytic theory). Throughout life the mouth assumes a prominent role in our link with the outside world—nutritionally, sexually, and through verbal communication.32 When individuals first meet, the mouth is often the first body part noticed. Given the prominence of the mouth, it is surprising that more people do not show sufficient concern for the appearance of their teeth and mouth.

Sex and age

Many stereotypes regarding sex have changed over the years. Still, the sexes have major differences that must be considered in a dental practice. The dentist needs to be aware of how patients view their own sexuality and the degree to which they wish to emphasize their masculinity or femininity.

The dentist also must consider a person’s age, both psychologic and chronologic. Through the use of veneers and bleaching, a more youthful appearance may be created. Although many people wish to appear more youthful, this is not universally true. As one woman so emphatically stated, “I am a little old lady and I want to look like one.”

Psychologic influences

Personality

An individual’s personality is the result of many factors. The degree to which facial, and specifically oral, appearance contributes to personality is difficult to ascertain. We have referred to just a few of the many attempts to broadly classify personality. The individual dentist must choose an approach for determining personality. Because personality is the filter through which relationships take place, an accurate assessment of a patient’s personality can be critical to the successful outcome of dental treatment.

Measurement and evaluation

A number of studies in the dental literature include personality variables in the assessment of patient satisfaction with their current dental condition,33 as well as with treatments involving complete dentures,34–37 partial dentures,38 temporomandibular disorders and chronic pain,39 orthognathic surgery,40 preprosthetic surgery,41 and orthodontics and prosthodontics.42

Many of these studies deal with captive audiences (e.g., veterans or patients at dental school clinics). Therefore the results are not extensively generalizable. Findings from one study sometimes conflicted with findings from another. No clear picture emerges. Very few studies have been done relating personality characteristics to esthetics, per se.

A variety of tools and techniques have been used to obtain information from patients. They include self-designed questionnaires, focused interviews, projective figure drawing, and standardized tests. Some specific tests that have been recommended include the Cattell 16 PF questionnaire (Form C)35 and the Cornell Medical Index.34 Dentists considering using standardized psychologic tests should seek the assistance of a psychologist trained in measurement and evaluation.

A decision is needed regarding how psychologic information will be obtained and recorded.43 Will it be an informal process based on an interview and observation of the patient, or will it be more formal? Will special forms be used to collect specific information? How will the forms be presented to patients in an effort to gain their cooperation? Who will interpret this information? How will this information be used?

Motivations, desires, and expectations

A host of factors may bring patients to a dental office initially, as well as cause them to return. Motivations may include the following:

1. The desire to be better able to eat and enjoy food

2. The desire to improve speech patterns

3. The fear of losing teeth through decay or fracture

4. The desire to be free of pain and discomfort

5. The desire to have fresh breath

6. The desire to enhance appearance or self-image to compete more effectively for attention or advancement

Not all patients are motivated by self-actualization; however, some may be moved in that direction.

In some instances the patients’ expectations are unachievable. Patients may have personality problems or interpersonal problems that they believe will be corrected or improved by the desired dental treatment. The dentist must be on guard for this problem and avoid getting into an unresolvable situation. The dentist should not promise more than can be delivered. The dentist should be sensitive to cues that the patients or those accompanying the patients reveal during the initial examination and interview process. The quintessential question that the practitioner must seek to answer is, “What motivated these patients to seek dental treatment?” If the patients are concerned primarily about appearance, what is the underlying motivation? If a particular problem has existed for a long time, what change in their lives caused them to seek help now?

The patients’ motivations or concerns form a starting point for developing a proper treatment plan. When patients realize that the dentist is truly listening to their concerns, they will be more likely to also consider the dentist’s limitations. For example, if the patient’s primary concern is the ability to eat, the most appropriate treatment—to improve mastication—should be addressed first. To achieve that objective, a complete or partial denture may be required. Once that need is addressed, improved esthetics will be incorporated later in connection with the design.

Determining motivation, coupled with a fairly accurate personality assessment, is crucial to successful treatment planning and ultimately to patient satisfaction with the treatment.

Basic information should be obtained from the patient upon entry into the office. This usually is obtained by means of a form. Auxiliary personnel set the tone in the manner in which they request this information from the patient. Much can be learned from observations of how the person studies the form, from unanswered questions, and from conversations with significant others while filling out the form. Seeking clarification or using information from this form to initiate conversation may elicit valuable information that can illuminate the patient’s personality and motivations. This can also help to determine whether the patient is able to articulate expectations in a clear manner.

Developing a trusting relationship

At times, patients find it difficult to reveal all the relevant aspects of their lives. The dentist may need to gain patients’ trust to enable them to open up and be forthright and honest. Roger’s client-centered therapy18 provides three qualities that help to engender trust:44

1. Accurate empathy involves the dentist’s sensitivity to patients’ feelings and an ability to communicate this awareness and acceptance of patients as unique individuals.

2. Nonpossessive warmth refers to the dentist’s nonjudgmental acceptance of the patient regardless of behavior. Patients should not be criticized for allowing their oral health to deteriorate.

3. Genuineness implies an openness and spontaneity on the part of the dentist.

Decision-making ability

Efforts should be made very early to engage patients in decision making. To the extent possible, patients should be active participants in their treatment.

Cooperation and follow-through

Optimal oral health and a beautiful smile require cooperation from the patient, as well as persistence in maintenance activities. Some people are “starters” but not “finishers.” Before initiating treatment, the dentist must adequately inform the patient of the need for follow-up care. Some reconstruction patients, for example, fail to accept responsibility for maintenance and end up losing all benefit of their extensive treatment.

Abnormalities and problem patients

Occasionally, “troubled” or “difficult” patients with irrational perceptions of self seek treatment or esthetic alterations that are unrealistic. They may be narcissistic, depressed, paranoid, or have labile or hysterical personalities. Often these individuals are skillful at masking their condition, especially during the interview process.

Only by careful listening over a period of time can the patients’ problems be identified. Patients may have unrealistic expectations or may be unable to internalize information provided by the dentist. These patients may be obsessed with perceived or minor flaws or may be unable to develop a trusting relationship.

Once a relationship has been established between a patient and a dentist, termination of that relationship must be handled very carefully to avoid a possible charge of abandonment (see Chapter 27). Treatment undertaken must be completed at least to the point at which the patient is not left in a precarious position. Before terminating a relationship, the dentist must make every effort to correct the problem, improve communication, and gain cooperation. These efforts may not be successful.

If the patient’s psychologic problems are severe, the dentist may determine that professional help is needed. Psychologic therapy does not fall within a dentist’s scope of practice without training and certification in this field. However, the dentist must appreciate the delicate nature of making a referral to a mental health professional; the referral should be made with care, empathy, and tact.

Not all problems can be anticipated and prevented. The dentist must think about the type of problems faced in an esthetic dental practice and consider an approach to dealing with these problems. It is logical to believe that the following problems are likely to occur:

1. The patient has an unrealistic esthetic expectation that cannot be satisfied.

2. The patient expects that an esthetic improvement will remove or correct deep-seated psychologic problems.

3. The patient is not satisfied with results that are technically and esthetically correct—in other words, the “it’s not me” phenomenon.

4. The patient is satisfied with the results, but family and friends are not.

5. The patient does not wish to have esthetics enhanced, and the dentist does.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses