Permanent tooth type

Calcification begins at

Crown formation completes at

Eruptiona

Maxillary

Mandibular

Central incisor

3–4 mo

4–5 y

7–8 y

6–7 y

Lateral incisor

Maxilla: 10–12 mo

4–5 y

8–9 y

7–8 y

Mandible: 3–4 mo

4–5 y

Canine

4–5 mo

6–7 y

11–12 y

9–11 y

First premolar

18–24 mo

5–6 y

10–11 y

10–12 y

Second premolar

24–30 mo

6–7 y

10–12 y

11–13 y

First molar

Birth

30–36 mo

5.5–7 y

5.5–7 y

Second molar

30–36 mo

7–8 y

12–14 y

12–14 y

Third molar

Maxilla: 7–9 y

>16 y

>16 y

Mandible: 8–10 y

Prevalence of DDE in the Permanent Dentition

Mouth and tooth prevalence are the most commonly used systems to report the prevalence data for DDE. Mouth prevalence is determined by the inclusion of any individual who has been found to have at least one tooth affected by the condition, while tooth prevalence illustrates the percentage of teeth affected per person. Mouth prevalence figures reflect the extent of the distribution of enamel defects in a population group because individuals who are mildly and severely affected are grouped together. Tooth prevalence indicates the proportion of teeth affected and hence reflects the severity of the condition [2].

Table 2.2 summarizes the prevalence of DDE in the permanent dentition as reported in the literature. Wide variations exist in the literature because of the use of various terminologies and the different diagnostic criteria employed to describe the enamel defects in the permanent dentition [21, 22, 24, 26]. Nevertheless, the majority of reports have failed to demonstrate any difference in the prevalence of enamel defects between girls and boys [12, 27]. Furthermore, for all types of enamel defects, the published mouth prevalence in the permanent dentition ranges from 9.8 % to 93 % [8, 26], while tooth prevalence figures range from 2.2 % to 21.6 % [26, 28].

Table 2.2

The prevalence figures, reported in the literature, for any type developmental defects of enamel in the permanent dentition of healthy children

|

Author

|

Year

|

Country

|

F level (ppm)

|

Age (years)

|

Prevalence %

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mouth

|

Tooth

|

|||||

|

Suckling et al. [3]

|

1985

|

New Zealand

|

1.0

|

12

|

56.6

|

18.8

|

|

Dooland and Wylie [4]

|

1989

|

Australia

|

1.0

|

8–9

|

–

|

25.5

|

|

0

|

15.6

|

|||||

|

Dummer et al. [5]

|

1990

|

UK

|

<0.1

|

15–16

|

50.1

|

5.71

|

|

26.2

|

11.8

|

|||||

|

Nunn et al. [6]

|

1992

|

UK

|

<0.2

|

15

|

64.1

|

38.7

|

|

–

|

57.5

|

|||||

|

1.0

|

78.9

|

59

|

||||

|

–

|

83.9

|

|||||

|

1.0–1.3

|

83.9

|

66.2

|

||||

|

–

|

81.5

|

|||||

|

Fyffe et al. [7]

|

1996

|

UK

|

–

|

13–14

|

48.7

|

–

|

|

Rugg-Gunn et al. [8]

|

1997

|

Saudi Arabia

|

0.25

|

14

|

75

|

–

|

|

0.80

|

82

|

–

|

||||

|

2.71

|

93

|

–

|

||||

|

Hiller et al. [9]

|

1998

|

Germany

|

<0.02

|

8–10

|

39.9

|

|

|

Dini et al. [10]

|

2000

|

Brazil

|

0.7

|

9–10

|

26.1

|

–

|

|

Jalevik et al. [11]

|

2001

|

Sweden

|

Low

|

7–8

|

33.3

|

–

|

|

Zagdwon et al. [12]

|

2002

|

UK

|

<0.1

|

7

|

14.5

|

7.2

|

|

Ekanayake and van der Hoek [13]

|

2003

|

Sri Lanka

|

<0.3

|

14

|

29

|

–

|

|

0.3–0.5

|

35

|

|||||

|

0.5–0.7

|

43

|

–

|

||||

|

>0.7

|

57

|

–

|

||||

|

Cochran et al. [14]

|

2004

|

Finland

|

<0.01

|

8

|

59

|

–

|

|

Greece

|

<0.01

|

43

|

–

|

|||

|

Iceland

|

0.05

|

54

|

–

|

|||

|

Portugal

|

0.08

|

49

|

–

|

|||

|

UK

|

<0.1

|

48

|

–

|

|||

|

The Netherlands

|

0.13

|

70

|

–

|

|||

|

Ireland

|

1.0

|

69

|

–

|

|||

|

Mackay and Thomson [15]

|

2005

|

New Zealand

|

–

|

9–10

|

51.6

|

–

|

|

Balmer et al. [16]

|

2005

|

UK

|

<0.1

|

8–16

|

–

|

27.3

|

|

Australia

|

0.9–1.1

|

51.6

|

||||

|

Wong et al. [17]

|

2006

|

Hong Kong

|

1.0 (1983)

|

12

|

92.1

|

–

|

|

0.7 (1991)

|

55.8

|

–

|

||||

|

0.5 (2001)

|

35.2

|

–

|

||||

|

Hoffmann et al. [18]

|

2007

|

Brazil

|

–

|

12

|

46.4

|

–

|

|

Muratbegovic et al. [19]

|

2008

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina

|

<0.1

|

12

|

32.8

|

–

|

|

Arrow [20]

|

2008

|

Australia

|

0.8

|

7

|

22

|

–

|

|

Kanagaratnam et al. [21]

|

2009

|

New Zealand

|

–

|

9

|

35a

|

–

|

|

Seow et al. [22]

|

2011

|

Australia

|

0.1

|

13.5b

|

58

|

–

|

|

Casanova-Rosado et al. [23]

|

2011

|

Mexico

|

–

|

6–12

|

7.5

|

–

|

|

Robles et al. [24]

|

2013

|

Spain

|

0.07

|

3–12

|

52

|

8.3

|

|

Vargas-Ferreira et al. [25]

|

2014

|

Brazil

|

–

|

8–12

|

64

|

–

|

Etiology of DDE in the Permanent Dentition

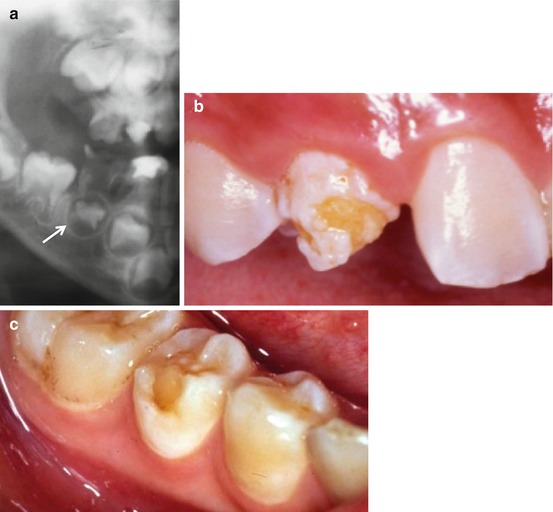

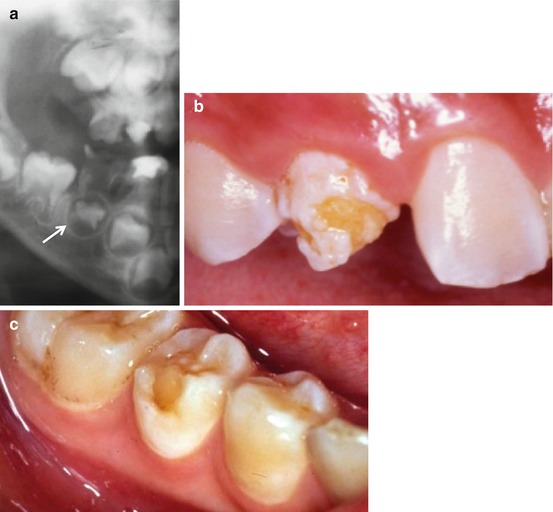

Enamel morphogenesis is a continuous, complex process that starts with the secretion of enamel matrix proteins followed by mineralization and finally maturation. This process has been shown to start at the cusps on the molars and the incisal part of the incisors, progressing to the cervical areas of the teeth [29]. However, there is still limited understanding of how mineralization progresses across the crowns of the teeth. This could be important in determining the timing of defects to relate to specific disturbances caused by systemic disorders. Disturbances in the different stages of enamel formation may result in a range of enamel defects with quite different clinical appearances and structural changes. Defective formation of the enamel matrix results in hypoplasia, a quantitative defect, depicted by generalized thinning or pitting types of defects (Fig. 2.1). Defective calcification of an otherwise normal fully developed organic enamel matrix results in hypomineralization, a qualitative defect (Fig. 2.2). This is seen clinically as changes in color and translucency of the enamel and presents as enamel opacities which can be either demarcated or diffuse [2, 30].

Fig. 2.1

Hypoplasia of the maxillary central incisors

Fig. 2.2

Hypomineralization and hypoplasia of the maxillary and mandibular incisor teeth

Although the etiology of enamel defects may be attributed to local, systemic, genetic, or environmental factors, most are likely to be multifactorial in nature. This makes it difficult to identify a single cause for many cases of DDE. The time frame of exposure and the mechanism underpinning the causative factors determine the presentation of these defects. Defects on a single tooth or only a few teeth suggest a local etiological factor e.g. a defect in a permanent tooth due to damage (trauma or infection) to its primary predecessor (Fig. 2.3a–c). Alternatively, a systemic factor (both short and longer term) may affect all the teeth that are developing during the time of the insult and lead to what is described as a chronological defect. Genetic factors can be considered separately. Defects caused by genetic factors are most often (although not always) generalized in distribution, affecting both the primary and permanent dentitions. They may present as either enamel defects alone as seen in amelogenesis imperfecta (see Chap. 5) or as enamel defects associated with other general genetic disorders/syndromes (see Chap. 4).

Fig. 2.3

(a) Caries in the mandibular second primary molar has led to the intra-radicular infection which has resulted in hypoplasia of the developing second premolar. (b) Hypoplasia of the maxillary permanent canine as a consequence of infection of the primary predecessor. (c) Hypoplasia in the form of missing enamel is exhibited by this mandibular second premolar following infection of the primary second molar

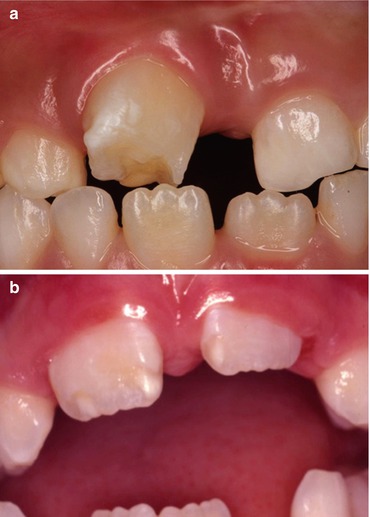

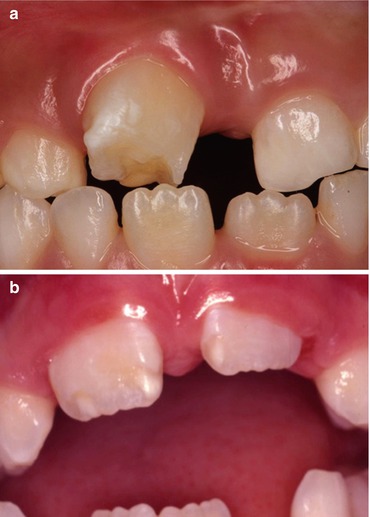

Enamel defects can be classified clinically as demarcated and diffuse opacities and hypoplasia. The location of isolated defects depends on the stage of amelogenesis at the time of the insult or injury [31]. The general consensus regarding the etiology of isolated opacities, which may be demarcated or diffuse and present as white, creamy, or yellow in color, is that amelogenesis is affected by a disturbance during the mineralization phase. It remains unclear why this would involve only an isolated patch of enamel on the crown and not the whole surface. Conversely, hypoplasia occurs when there is a disturbance during the secretory stage of amelogenesis while the enamel is only partly mineralized. Thus, enamel defects with similar presentations may have been caused by a variety of etiological factors. Furthermore, the same etiological factor can produce enamel defects with different presentations depending on the timing of the insult. Examples of this are commonly seen following primary tooth trauma. When a maxillary anterior primary tooth is intruded in infancy (during the first year of life), the crown of the permanent successor may suffer severe structural damage with missing enamel and even dilaceration of the root or the crown, while an intrusion in the later preschool years may only cause an isolated labial hypomineralized enamel opacity on the permanent successor (Fig. 2.4a, b).

Fig. 2.4

(a) Hypoplasia of the maxillary permanent incisor tooth as a consequence of trauma to the predecessor. (b) Hypomineralization and hypoplasia of the maxillary central incisor teeth as a consequence of trauma to the predecessor

Determining the Etiology

Based on the number of teeth affected, the possible etiological factors for DDE in permanent teeth can be categorized as being local or general. However the evidence is equivocal, with the majority of published reports being animal studies or case reports of children with specific systemic disorders. The putative etiological factors reported in the literature are summarized in Table 2.3. Only a few of these factors have good evidence supporting a direct causal effect, e.g., trauma to a primary predecessor or high levels of ingested fluoride during early childhood.

Table 2.3

List of etiological factors, reported in the literature, responsible for the formation of enamel defects in the permanent dentition

|

Local

|

Systemic

|

Hereditary conditions

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Perinatal and neonatal

|

Postnatal

|

||

|

Trauma

|

Neonatal hypocalcemia

|

Nutritional and gastrointestinal disturbances resulting in hypocalcemia and vitamin D deficiency

|

22q11 deletion syndrome

|

|

Primary tooth

|

|||

|

Surgery

|

|||

|

Distraction osteogenesis

|

|||

|

Tooth forceps

|

|||

|

Chronic periapical infection in a primary tooth

|

Severe perinatal and neonatal hypoxic injury

|

Bacterial and viral infections associated with high fever

|

Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy

|

|

Cleft lip and palate

|

Prolonged delivery

|

Exanthematous diseases

|

Candidiasis endocrinopathy syndrome

|

|

Radiation

|

Prematurity

|

Juvenile hypothyroidism

|

Cleidocranial dysostosis

|

|

Burns

|

Low birth weight

|

Hypothyroidism

|

Celiac disease

|

|

Osteomyelitis

|

Twins

|

Hypogonadism

|

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

|

|

Jaw fracture

|

Cerebral injury

|

Phenylketonuria

|

Congenital contractual arachnodactyly

|

|

Neurological disorders

|

Alkaptonuria

|

Congenital unilateral facial hypoplasia

|

|

|

Hyperbilirubinemia

|

Renal disorders

|

Ectodermal dysplasias

|

|

|

Prolonged neonatal diarrhea and vomiting

|

|||

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses