Introduction

The aim of this study was to compare the presence of alveolar defects (dehiscence and fenestration) in patients with Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusions and different facial types.

Methods

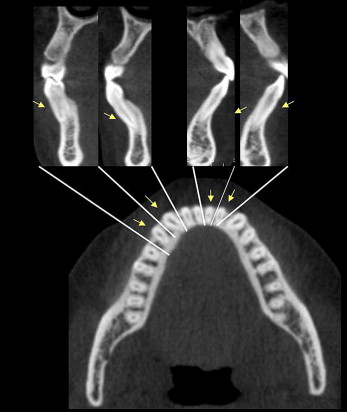

Cone-beam computed tomography records of 79 patients with Class I and 80 patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusions and no previous orthodontic treatment were evaluated. The sample included 4319 teeth. All teeth were analyzed by 2 examiners who evaluated sectional images in axial and cross-sectional views to check for the presence or absence of dehiscence and fenestration on the buccal and lingual surfaces.

Results

Dehiscence was associated with 51.09% of all teeth, and fenestration with 36.51%. The Class I malocclusion patients had a greater prevalence of dehiscence: 35% higher than those with Class II Division 1 malocclusion ( P <0.01). There was no statistically significant difference between the facial types.

Conclusions

Alveolar defects are a common finding before orthodontic treatment, especially in Class I patients, but they are not related to the facial types.

Editor’s comment

It’s an easy call to be concerned with dehiscences and fenestrations when you discover them after orthodontic care, but is there a way to predict their development before treatment? Specifically, are there types of tooth movements or skeletal relationships that predict these sequellae? The aim of this study was to use cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) to compare the presence of dehiscence and fenestration between patients with Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusions and various facial types.

To conduct this study, pretreatment patients were selected from a German private practice accustomed to taking CBCT scans. Images were made with an i-CAT scanner, with 47.7 mA, 120 kV, 40-second exposure time, and isotropic voxel size of 0.25 × 0.25 × 0.25 mm. The imaging protocol included a 6-in field of view to capture the entire facial anatomy. Totals of 79 Class I and 80 Class II Division 1 malocclusion patients met the inclusion criteria.

Dehiscence (51.09%) was found more often than fenestration (36.51%). The differences in relation to dehiscence and fenestration between Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusion constitute new evidence. It is thought that tooth inclination might explain these differences. In orthodontics, alveolar thickness of less than 0.5 mm is a “quasi defect,” because it is extremely thin and should be considered a defect as well. This strongly indicates caution in orthodontic movement. These data suggest that the prevalence of dehiscence and fenestration is a common anatomic finding, affecting different facial types, and that the vertical position of the jaws does not influence the presence of dehiscence or fenestration.

What does this mean for clinicians? These data suggest that greater caution is needed about tooth proclination in the mandible, especially in the incisor region, a fact emphasized by other authors for years. Maxillary canines and first premolars also showed great prevalence of dehiscence in this study. This offers an important clue to procedures involving rapid expansion of the maxilla, because the first premolars, and sometimes the canines, are the support teeth for orthopedic devices. How important is it to use 3-dimensional imaging before starting orthodontic treatment? The authors base their answer on the data, stating, “in patients needing more extensive orthodontic movements, and those who have a less favorable gingival biotype such as thin attached gingiva, a 3-dimensional diagnosis of alveolar bone is recommended.” Yes, alveolar defects are common before orthodontic treatment, mainly in Class I patients, and these defects are not related to facial type.