Dry Mouth—Xerostomia and Hyposalivation

Prevention of Oral Complications

Dry Mouth—Xerostomia and Hyposalivation

Crispian Scully and Jane Luker

Introduction

Introduction

Dry mouth (xerostomia) is the most common salivary complaint. Up to 30% of various populations self-report dry mouth or have proven low salivary flow rates (hyposalivation). Dry mouth is the most common salivary complaint—not a disease, but a symptom.

Apart from drugs, the main causes are Sjögren syndrome and cancer therapy. This chapter focuses mainly on Sjögren syndrome, as xerostomia-related cancer therapy is discussed in Chapter 42. Treatment of hyposalivation is largely palliative and preventative in nature. This chapter summarizes the area and highlights recent advances and future directions; several recent reviews have covered this field comprehensively.1,2

Definition

Definition

Xerostomia and hyposalivation are not synonymous; xerostomia is the subjective symptom of oral dryness, while hyposalivation (hyposialia) is a reduction in saliva production—best determined objectively.

Clinical Features

Clinical Features

Oral complaints frequently include xerostomia, sore mouth or burning sensation, having to put a glass of water on the bedside table to drink at night; and difficulties in eating dry foods such as biscuits (the cracker sign), swallowing, speaking for long periods of time, and controlling dentures.

Chronic complications of hyposalivation may include tooth demineralization and dental caries,3 gingival inflammation, and oral infections (candidosis and bacterial sialadenitis).

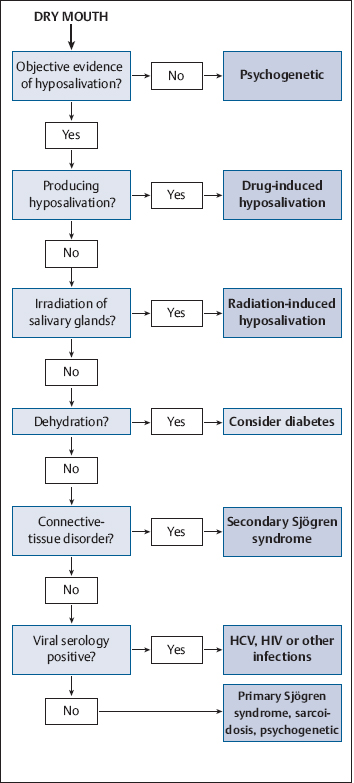

Diagnostic Work-Up (Fig. 14.1)

Diagnostic Work-Up (Fig. 14.1)

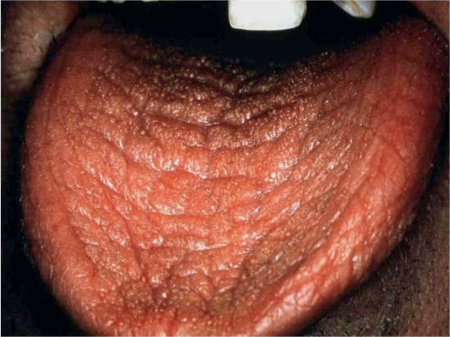

An examining dental mirror may often stick to the mucosa, there may be a lack of salivary pooling in the floor of the mouth, saliva flows poorly if at all from the ducts of the major glands on stimulation or palpation, and any saliva present tends to be viscous and appear frothy. There may also be food residues on teeth or mucosae and a characteristic tongue appearance, with a lobulated, usually red surface with partial or complete depapillation (Fig. 14.2).

Occasionally, hyposalivation is suspected when there is a particular predisposition to caries.4

Occasionally, hyposalivation is suspected when there is a particular predisposition to caries.4

Fig. 14.1 A diagnostic decision algorithm for dry mouth. HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Salivary Flow Rate

The normal salivary flow rate varies widely from person to person, and so unless baseline salivary flow rates for individual patients are known, it is not possible to determine whether there has been a reduction in salivary flow. The unstimulated whole saliva flow rate (USFR) measurement is commonly used; this is a simple draining test for 5 minutes at rest. If the amount is less than or equal to 0.1 mL/min, the patient has hyposalivation. Normal and reference values are shown in Table 14.1. Hyposalivation has a large impact on health-related quality of life (HR–QOL), employment, and disability of patients.4 Any factor that increases illness severity or distress can result in an increase in dryness.5

Salivary flow rates also vary over time and should therefore be determined on several occasions. Many patients who complain of a dry mouth (xerostomia) lack objective evidence of hyposalivation, and in some this may reflect psychogenic conditions. The main causes of genuine hyposalivation are drugs (those with anticholinergic or sympathomimetic activity), cancer therapies, Sjögren syndrome, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, sarcoidosis, and dehydration (Table 14.2).

Fig. 14.2 Xerostomia, showing dry mucosae.

|

|

Normal |

Hyposalivation |

|

Unstimulated (resting) |

0.3–0.4 mL/min |

< 0.1 mL/min |

Many older patients complain of a dry mouth: indeed, in the older age groups, 16%–25% report xerostomia, but this is usually caused by drugs.6 In general, there are no age-associated differences in parotid or submandibular salivary flow rates in healthy men and women.7

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Sjögren Syndrome

Sjögren syndrome (SS) can present with xerostomia, salivary gland swelling, and secondary oral manifestations such as dental caries, oral candidosis, oral malodor, and oral ulcerations. These manifestations are common in patients with SS and may be the first identified features of the disease in approximately half of the patients. Their identification is important for early diagnosis. Most SS patients also consider oral complications to be a major factor in the deterioration of their quality of life,8 and treating these symptoms should therefore be a priority.

Diminished salivary gland function and parotid gland enlargement are amongst the most prevalent manifestations in SS. Unstimulated whole saliva flow is an independent predictor of deteriorated exocrine gland function.9

|

Interference with neural transmission |

|

|

|

Dehydration |

|

|

|

Cancer therapy |

|

|

|

Salivary gland disease |

|

|

CMV, cytomegalovirus; CNS, central nervous system; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV-1, human T–cell lymphotrophic virus type I.

Xerostomia in SS is generally associated with reduced quantities of saliva rather than altered properties, and reduced sulfated oligosaccharide levels in salivary mucous acini may result in altered sulfation of sulfated and sialylated oligosaccharides, which may underlie xerostomia.10

|

Strategy |

Details |

|

Minimizing radiation exposure doses |

Ipsilateral irradiation treatment of the primary site and ipsilateral neck |

|

Positioning devices, shielding and conformational field planning |

Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) |

|

Helical tomotherapy (Hi-Art tomotherapy) |

|

|

Radiation-protective agents |

Amifostine, pilocarpine |

|

Surgical salivary gland repositioning out of the planned radiotherapy field |

Superior to pilocarpine |

Cancer Therapy

Bone-marrow (hematopoietic stem cell) transplants and cancer treatment (especially irradiation of the major salivary glands) may be associated with troublesome xerostomia. While the direct effects of some cancer therapies on salivary function frequently cause xerostomia, 18%–19% of both hospitalized cancer patients and noncancer patients may also suffer from dry mouth,11 suggesting a strong role for anxiety and/or depression and/or drugs in hospitalized patients.

Irradiation of the major salivary glands, common in treatment for cancers of the head and neck, thyroid, lymphomas, and hematopoietic stem cell transplants,12 causes salivary flow rates to fall dramatically during the first 2 weeks of radiotherapy, and both the parotid and other major glands can be similarly affected. Radiotherapy causes acinar cell apoptosis, leading to a change in saliva quantity and quality within 1–2 weeks of the start of radiotherapy at a cumulative dose of about 10 Gy; salivary function falls as the radiotherapy dose increases and, at a total dose > 50 Gy, virtually complete hyposalivation can follow.

Patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy or surgery, report xerostomia as one of the most frequent complaints, and this has a significant impact on the more general quality of life.13 Any recovery of salivary function takes place mostly within 1 year after radiotherapy.14

Apart from minimizing radiation doses, a range of strategies are available to minimize radiation-induced salivary gland damage (Table 14.3).

Treatment

Treatment

There is little correlation between patients’ symptoms and objective tests of salivary flow, so the clinical management is best based on the symptoms. Management is multidisciplinary and multimodal and essentially involves the use of salivary substitutes and/or salivary stimulants. It begins with simple measures, such as:

The patient sipping water or other fluids, protecting the lips with lip salve, and modifying eating (e.g., small bites of food, eaten slowly) and diet (creamy foods such as casseroles or soups; cool foods with a high liquid content such as melon or ice cream; and moistening foods with water, gravies, sauces, extra oil, dressings, sour cream, mayonnaise, or yoghurt).

The patient sipping water or other fluids, protecting the lips with lip salve, and modifying eating (e.g., small bites of food, eaten slowly) and diet (creamy foods such as casseroles or soups; cool foods with a high liquid content such as melon or ice cream; and moistening foods with water, gravies, sauces, extra oil, dressings, sour cream, mayonnaise, or yoghurt).

The patient avoiding: mouth breathing; drugs that produce xerostomia; alcohol (including in mouthwashes); smoking; caffeine (coffee, some soft drinks); dry foods such as biscuits (or they can be moistened in liquid first); spicy foods; and oral healthcare products containing sodium lauryl sulfate, which may irritate the mucosa.

The patient avoiding: mouth breathing; drugs that produce xerostomia; alcohol (including in mouthwashes); smoking; caffeine (coffee, some soft drinks); dry foods such as biscuits (or they can be moistened in liquid first); spicy foods; and oral healthcare products containing sodium lauryl sulfate, which may irritate the mucosa.

Mouth-Wetting Agents (Saliva Substitutes)

Mouth-wetting agents may help relieve xerostomia symptoms even after radiotherapy.15 Many mouth-wetting agents are available, and there are some differences in their performance and various advantages and disadvantages. Mouth-wetting agents based on mucin may not be acceptable to various religious or cultural groups (some Muslims, Hindus, Jews, Rastafarians, and others). Mouth-wetting agents based on carboxymethylcellulose are particularly useful if they contain fluoride and are therefore protective against caries.16 A mouthwash and oral gel containing the antimicrobial proteins lactoperoxidase, lactoferrin, and lysozyme has been found to improve subjective and clinical aspects of xerostomia.17

Salivary Stimulants

In patients with residual salivary gland function, salivary stimulants appear to be more beneficial than simply using mouth-wetting agents. Salivary stimulation is readily and simply achieved using chewing gums and taste stimulation with citrus or other flavors, but sugar-free preparations should be chosen to avoid the risk of dental caries (Table 14.4). Systemic medications (sialogogues) may also stimulate salivation, but can have adverse effects.

Pilocarpine is a parasympathomimetic agent derived from the “slobber plant” (Pilocarpus jaborandi), which can increase salivation even after radiotherapy18 or opioid use.19 Pilocarpine produces maximum saliva stimulation after 1 hour, and the effect continues for 2–3 hours. Adverse effects may include sweating, flushing, urinary urgency, and gastrointestinal upset. It is contraindicated in narrow-angle glaucoma, acute iritis, or uncontrolled asthma.

|

Local/topical |

|

|

|

Systemic sialagogues |

|

Cholinergic agents

|

|

Other agents

|

Cevimeline is another parasympathomimetic agent, with a similar pharmacological profile to that of pilocarpine, which augments the salivary flow rate and may also increase the secretion of some salivary digestive and/or defense factors (amylase and immunoglobulin A).20

Bethanechol is another possible choice of parasympathomimetic agent.21

The following therapies with some potential objective beneficial effects are currently under trial: salivary irrigation, certain drugs (Capparis masaikai Levl., nizatidine, rebamipide, Xialine), hypnosis, acupuncture, electrostimulation, and stem cell or gene therapy.

The following therapies with some potential objective beneficial effects are currently under trial: salivary irrigation, certain drugs (Capparis masaikai Levl., nizatidine, rebamipide, Xialine), hypnosis, acupuncture, electrostimulation, and stem cell or gene therapy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Medications/drugs

Medications/drugs Conditions affecting the CNS

Conditions affecting the CNS Alzheimer disease

Alzheimer disease Psychogenic disorders

Psychogenic disorders Anxiety states

Anxiety states Hypochondriasis

Hypochondriasis Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa Autonomic dysfunction (dysautonomia, ganglionic neuropathy)

Autonomic dysfunction (dysautonomia, ganglionic neuropathy) Endocrine (diabetes, hypothyroidism)

Endocrine (diabetes, hypothyroidism) Cholinergic dysautonomia

Cholinergic dysautonomia Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus Diabetes insipidus

Diabetes insipidus Diarrhea and vomiting

Diarrhea and vomiting Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia Renal disease

Renal disease Severe hemorrhage

Severe hemorrhage Irradiation (radiotherapy or radioactive iodine)

Irradiation (radiotherapy or radioactive iodine) Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy Chemoradiotherapy

Chemoradiotherapy Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, bone-marrow transplantation, chronic graft-versus-host disease

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, bone-marrow transplantation, chronic graft-versus-host disease Inflammatory disorders (Sjögren syndrome, lupus sialadenitis, sarcoidosis)

Inflammatory disorders (Sjögren syndrome, lupus sialadenitis, sarcoidosis) Infections (HIV, HCV, EBV, CMV, HTLV-1)

Infections (HIV, HCV, EBV, CMV, HTLV-1) Deposits (amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, hyperlipidemia)

Deposits (amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, hyperlipidemia) Aplasia

Aplasia Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis Ectodermal dysplasia

Ectodermal dysplasia Taste stimulation; sugar-free (diabetic) sweets

Taste stimulation; sugar-free (diabetic) sweets Masticatory stimulation; chewing gums (containing xylitol or sorbitol, not sucrose)

Masticatory stimulation; chewing gums (containing xylitol or sorbitol, not sucrose) Oral rinses, gels, mouthwashes

Oral rinses, gels, mouthwashes Acupuncture

Acupuncture Pilocarpine (Salagen)

Pilocarpine (Salagen) Cevimeline (Evoxac)

Cevimeline (Evoxac) Bethanechol (Urecholine)

Bethanechol (Urecholine) Physostigmine

Physostigmine Anethole trithione (Sialor)

Anethole trithione (Sialor)