http://evolve.elsevier.com/Haveles/pharmacology

Gastrointestinal drugs

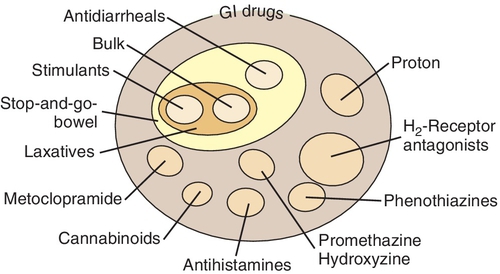

Many drugs, both over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription, are used for gastrointestinal diseases (Figure 15-1). Some are used to treat specific gastrointestinal diseases, and others to provide symptomatic relief.

Gastrointestinal Diseases

Ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are common gastrointestinal tract diseases. With the discovery of the etiology of ulcers, the incidence of ulcers in the population has decreased substantially. Nonspecific complaints for GERD include burping, cramps, flatulence, fullness, and congestion in the stomach. The gastrointestinal tract is highly susceptible to emotional changes because it is innervated by the vagus nerve associated with the autonomic nervous system.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

GERD, or “heartburn,” is the most prevalent gastrointestinal disease in the U.S. population. In this condition, the stomach contents, including the acid, reflux, or flow backward through the cardiac sphincter, up into the esophagus. Because the esophagus is not designed to endure the stomach’s acid, irritation, inflammation, and erosion can occur. The pain from the inflamed esophagus may be severe and located in the middle of the chest, causing it to be interpreted as a heart attack and trigger an emergency room visit. The main problem is t inadequate function of the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing backflow to occur. The symptoms of GERD are exacerbated by eating large meals (blowing up a balloon [stomach] increases the backpressure) and by assuming the supine position (gravity is no longer helping).

Close to 3 million Americans suffer from Barrett’s esophagus. This disorder occurs when the cells of the lower esophagus become damaged as a result of repeated exposure to stomach acid. This causes a change in the color and composition of esophageal cells. Barrett’s esophagus is most often diagnosed in patients with long-term GERD; however only a small percentage of patients with GERD go on to develop Barrett’s esophagus. A diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is of concern because a small number of patients who have it can go on to have esophageal cancer. Barrett’s esophagus is normally diagnosed through endoscopy. Patients who present to a dental practice without a diagnosis of GERD or Barrett’s esophagus but with symptoms of taste changes and enamel erosion should be referred to their primary care physicians for further evaluation.

Lifestyle changes that can reduce symptoms include avoiding eating for 4 hours before bedtime, eating smaller meals more often, and raising the head of the bed with bricks or using several pillows. Some patients with either disorder that is not treated may have such severe symptoms that they cannot sleep lying down and must sit in a chair.

GERD is treated in two ways: one is to decrease the acid in the stomach and the other is to constrict the cardiac sphincter (the muscle between the stomach and the esophagus). If the sphincter is tighter, it is less likely that the contents will flow back into the esophagus. The histamine2 (H2) blocking agents and the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce or eliminate the stomach’s acid. The gastrointestinal stimulants act by increasing the tone of the cardiac sphincter. Sometimes both of these approaches are required to make the patient asymptomatic. Antacids are used for acute relief of symptoms.

Ulcers

Ulcers may occur in the stomach or small intestine. In the past, it was thought that ulcers were caused by “too much acid.” However, in the last decade it has been determined that most ulcers are related in some way to the presence of the organism Helicobacter pylori. Many ulcers can now be cured by using a combination of one or more antibiotics and an H2-blocker or a PPI to reduce the acid in the stomach. Some ulcers, especially in the elderly, are secondary to the long-term use of the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAID-induced ulcers occur because NSAIDs inhibit synthesis of prostaglandins (PGs), which are cytoprotective to the stomach.

Dental Implications

Box 15-1 summarizes the treatment of dental patients with peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and GERD.

Drugs used to treat gastrointestinal diseases

Histamine2-Blocking Agents

Histamine2 receptor antagonists block and inhibit basal and nocturnal gastric acid secretion by competitive inhibition of the action of histamine at the H2-receptors of the parietal cells. They also inhibit gastric acid secretion stimulated by other agents such as food and caffeine. All the members of this group, which are now available OTC, are listed in Table 15-1. Cimetidine (sye-MET-i-deen) (Tagamet) is discussed as the prototype. However, it has largely been replaced by famotidine, ranitidine, and nizatidine because of their more tolerable side effect profiles.

Uses

This group is indicated for the treatment of ulcers and the management of the symptoms of ulcers and GERD. H2-blockers should be administered with meals and at bedtime. For maintenance, if only one dose is needed daily, the bedtime dose is most effective. If taken Twice-daily agents are taken in the morning and at bedtime.

Because smoking increases acid production and reduces the effect of the H2-blockers, smoking cessation assistance should be offered to dental patients who smoke.

Adverse Reactions

The side effects of cimetidine include central nervous system (CNS) effects such as slurred speech, delusions, confusion, and headache. Because cimetidine binds with the androgen receptors, it has antiandrogenic effects such as gynecomastia, reduction in sperm count, and sexual dysfunction (e.g., impotence). Unlike cimetidine, neither ranitidine nor famotidine has been found to possess antiandrogenic activity. Famotidine has been associated with dry mouth and taste alterations. Cimetidine’s hematologic effects include granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. Reversible hepatitis and abnormal liver function values have been reported with all of the H2-blockers.

Cimetidine inhibits liver microsomal enzymes responsible for the hepatic metabolism of some drugs (cytochrome P-450 oxidase system), resulting in a delay in elimination and an increase in serum levels of some drugs, possibly producing toxicity. Ranitidine inhibits the P-450 enzymes much less than does cimetidine, and the other H2-blockers have no effect on the P-450 enzymes. A few examples of drugs that are metabolized by the P-450 pathway are warfarin, metronidazole, lidocaine, phenytoin, theophylline, diazepam, and carbamazepine.

Dental Drug Interactions

The metabolism of the following drugs occasionally used in dentistry may be reduced by the administration of cimetidine:

Proton Pump Inhibitors

PPIs are potent inhibitors of gastric acid secretion that are effective (in combination with the antibiotics) in healing duodenal ulcers and in monotherapy for the acute treatment and maintenance therapy of GERD. The mechanism of action involves the inhibition of the hydrogen/potassium adenosine triphosphatase (H +/K + -ATPase) enzyme system at the surface of the gastric parietal cell. Currently available PPIs are listed in Table 15-1. PPIs heal ulcers more rapidly than H2

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses