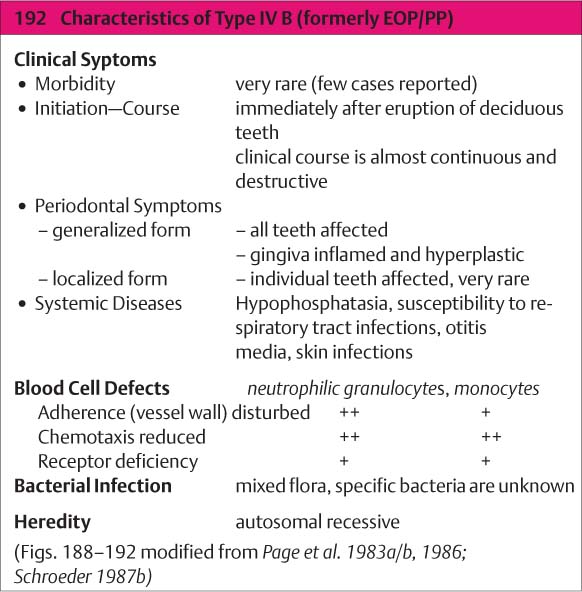

Types of Plaque-associated Periodontal Diseases

Gingivitis—Periodontitis

The general term “periodontal diseases” encompasses inflammatory as well as recessive alterations within the gingiva and the periodontium (Page & Schroeder 1982; AAP 1989, 1996; Ranney 1992, 1993; Lindhe et al. 1997; Armitage 1999).

While gingival recession may have various etiologies, including morphologic, mechanical (improper oral hygiene) and even functional (p. 155), gingivitis and periodontitis are plaque-associated diseases. Today it is becoming more and more clear that bacteria alone, including even the so-called periodontopathic bacteria, can always elicit gingivitis, but not periodontitis in every case. The initiation of periodontitis, its speed of progress and the expression of its clinical picture also involve the responsibility of negative host factors and additional so-called risk factors (Clark & Hirsch 1995). One of the most important are defects of the acute host response resulting from functional disturbances of polymorphonuclear granulocytes (PMN), other insufficient immunologic reactions, and the predominance of pro-inflammatory mediators, many of which are genetically determined. The now well established alterable risk factors include, particularly, “unhealthy” habits such as smoking, alcohol consumption and a less than well-rounded diet (p. 22).

Furthermore, systemic disorders and syndromes are usually un alterable, obligate or facultative risk factors for periodontitis. In this regard, especially Diabetes mellitus is viewed as prejudicial (p. 132). Finally, the entire social environment of an individual can play an important role for the initiation and propagation of periodontitis (pp. 22, 51).

All of the factors discussed in the chapter “Etiology and Pathogenesis” (p. 21) enhance the occurrence of all diseases, including periodontitis. Thus, periodontitis is considered to be of multifactorial etiology. It remains difficult in the face of a manifest disease process to differentiate the “etiologic weight” of bacteria on the one hand and the host response and risk factors on the other hand, or to differentiate between and among such etiologic factors. The contemporary, on-going search for responsible “risk markers” is therefore very important.

Today, clinicians can use additional clinical parameters such as bleeding on probing, the severity of the disease in relation to patient age, as well as microbiologic and genetic tests in order to establish some semblance of a proper diagnosis and prognosis (p. 165).

In the future, more precise research into the reduced host defense occasioned by immunologic defects, as well as the type and quantity of participating cytokines and inflammatory mediators (e. g., in sulcus fluid, blood or saliva) will simplify diagnosis and permit more definitive predictions about the probable course of the disease, as well as indicating more targeted therapy.

Classification of Periodontal Diseases—Nomenclature

Most recent research results and clinical knowledge have led the nomenclature of the periodontal diseases into a state of constant change. Indeed, because of varying interpretations of scientific results, it has often led to conflict between authors and scientific societies.

Relatively recently, the new nomenclature from the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP, 1989) was generally accepted. This classification distinguished between gingivitis (G) and adult periodontitis (AP) of the following types: Early-onset periodontitis (EOP) with further subclassifications (PP, JP, RPP), periodontitis associated with systemic diseases (PSD), the acute necrotizing, ulcerative gingivoperiodontitis (ANUG/P), and the therapy-resistant, refractory periodontitis (RP).

After only a few years, however, this “new” classification was no longer satisfactory! The European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) proposed in 1993 a new classification, and even this was modified in 1999/2000 during an international workshop in collaboration with the AAP (Armitage 1999).

The “old” classification from 1989 was criticized because it placed too much weight upon the age of the patient vis-àvis the initiation of the disease process. For example “adult periodontitis” (AP) as a chronic disease could also be observed in adolescents; rapidly-progressing periodontitis (RPP) was observed not only in young individuals (EOP) but also could appear “suddenly” in older patients; the localized, juvenile form (LJP) was not observed only in young patients. Furthermore, “refractory periodontitis” (RP) cannot be viewed as a specific disease entity, because following treatment for periodontitis the disease might recur or the disease might simply not respond to the therapy.

Classification 1999/2000

This third edition of the Color Atlas of Periodontology consistently utilizes the most recent nomenclature (1999/2000), but several “old” and well-known terms are used for occasional clarification, e. g., LJP, which is now classified as “Type III, aggressive periodontitis A, localized.”

The table below is a brief summary of the new nomenclature to assist the dentist. The complete and extremely comprehensive “Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions” can be found in the appendix (“Classifications,” p. 519). Some view the new classification as too expansive and comprehensive, while others criticize it as incomplete!

Classification of Periodontal Diseases (International Workshop of the AAP/EFP, 1999)

| Type I | Gingival Diseases

A Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases B Non-Plaque-Induced Gingival Lesions |

|

| Type II | Chronic Periodontitis

A Localized B Generalized |

|

| Type III | Aggressive Periodontitis

A Localized B Generalized |

|

| Type IV | Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Disease A Associated with Hematological Disorders

B Associated with Genetic Disorders C Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) |

|

| Type V | Necrotizing Periodontal Disease

A Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis (NUG) B Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis (NUP) |

|

| Types VI-VIII | Further forms as well as transitions and “status pictures” of the diseases described, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the new classifications are described in details (pp. 519–522) and in the original publications. | |

Gingivitis

Plaque-induced Gingivitis, Gingivitis Simplex, Type I A 1

Gingivitis is ubiquitous. It is a bacterially-elicited inflammation (non-specific mixed infection) of the marginal gingiva (Löe et al. 1965).

In the chapter “Etiology and Pathogenesis,” the development and progression of gingivitis from healthy tissue to an early lesion and on to established gingivitis was described (pp. 56–59; Page & Schroeder 1976, Kornman et al. 1997). In children, the early lesion (gingivitis) with T-cell dominance can persist for many years; on the other hand, in adults, the persistent lesion is almost exclusively established gingivitis (with plasma cell dominance), which can assume quite variable clinical severity. It is possible, clinically and pathomorphologically, to differentiate gingivitis into mild, moderate and severe, although this classification is relatively subjective.

For a more precise diagnosis of gingival inflammation, it is prudent to employ accepted indices that quantitate bleeding upon probing of the gingival sulcus.

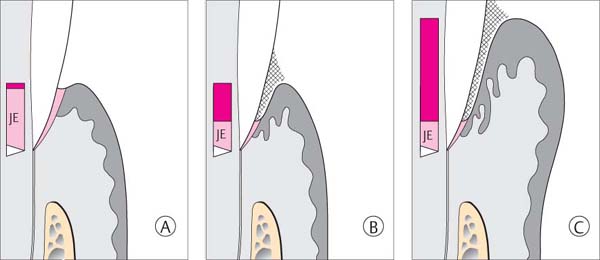

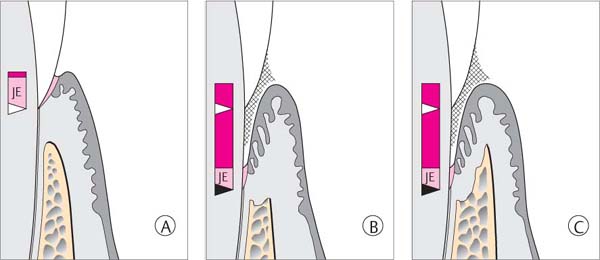

144 Sulcus and Gingival Pocket

A Sulcus: Histologically, in healthy gingiva the sulcus is maximally 0.5 mm deep. However, upon probing, the probe may penetrate the junctional epithelium up to 2 mm.

B Gingival Pocket: In gingivitis, the coronal portion of the junctional epithelium detaches from the tooth. There is no true attachment loss.

C Pseudopocket: With swelling of the gingiva, a pseudopocket may develop.

The borderline between healthy gingiva and gingivitis is difficult to ascertain. Gingiva that appears to be clinically healthy will nevertheless almost always exhibit histologically a mild inflammatory infiltrate. If there is an increase in clinical and histologic inflammation, one observes lateral proliferation of the junctional epithelium. The JE becomes detached from the tooth at its marginal aspect, as the bacterial front progresses between the tooth surface and the epithelium. The result is a gingival pocket.

In cases of severe gingivitis with edematous swelling and hyperplasia of the tissues, a clinical pseudopocket often forms.

Gingival pockets and pseudopockets are not true periodontal pockets because no connective tissue attachment loss has occurred, nor has there been apical proliferation of the junctional epithelium. However, because the milieu of pseudopockets is an oxygen-poor environment, periodontopathic anaerobic microorganisms can thrive.

It is true that gingivitis may develop into periodontitis. However, even without treatment, gingivitis can persist over many years in a stationary manner, exhibiting only minor variations in intensity (Listgarten et al. 1985). With treatment, gingivitis is fully reversible.

Histopathology

The clinical and histopathologic pictures of established gingivitis are well correlated (Engelberger et al. 1983).

The mild infiltration that occurs even in clinically healthy gingiva may be explained as a host response to the small amount of plaque that is present even in a clean dentition. Such plaque is composed of non-pathogenic or mildly pathogenic microorganisms, primarily gram-positive cocci and rods.

As plaque accumulation increases, so does the severity of clinically detectable inflammation, as evidenced by the quantity and expanse of inflammatory infiltrate. The subepithelial infiltrate consists primarily of differentiated Blymphocytes (plasma cells), with a smaller number of other types of leukocytes.

With increasing inflammation, more and more PMN granulocytes transmigrate the junctional epithelium. As a consequence, the junctional epithelium takes on the characteristics of a pocket epithelium (p. 104, Fig. 209; Müller-Glauser & Schroeder 1982), but without any significant apical proliferation.

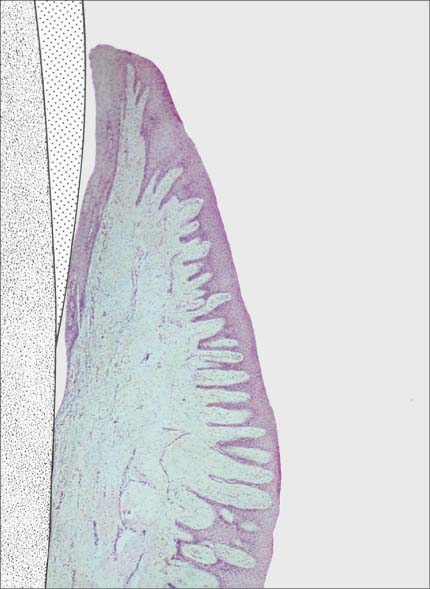

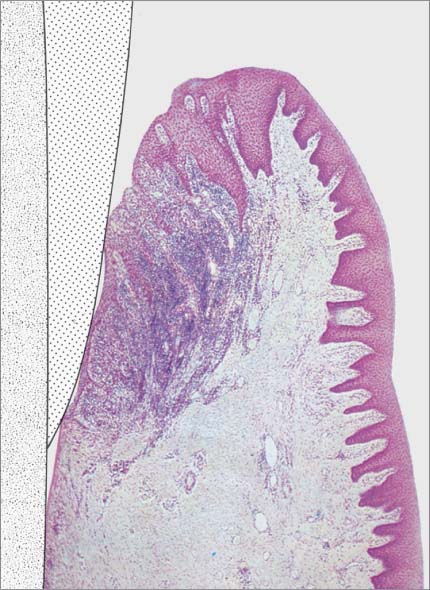

145 Healthy Gingiva (left)

Even in clinically healthy gingiva (GI = 0, PBI = 0), one can observe a very discrete sub-epithelial inflammatory infiltrate. Scattered PMNs transmigrate the junctional epithelium, which remains for the most part intact (HE, × 10).

146 Mild Gingivitis (right)

As clinical inflammation increases (GI = 1, PBI = 1) the amount of inflammatory infiltrate increases and collagen is lost (Masson stain, × 10).

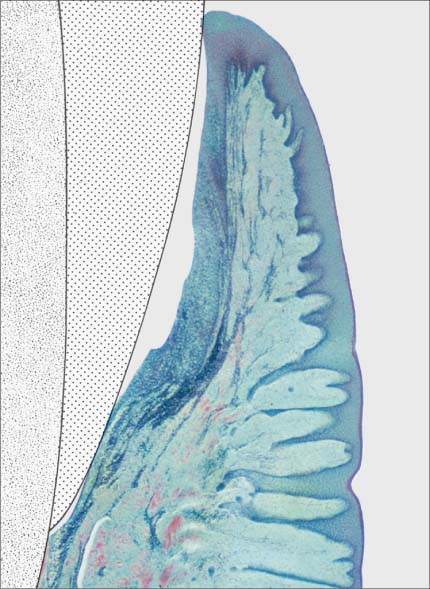

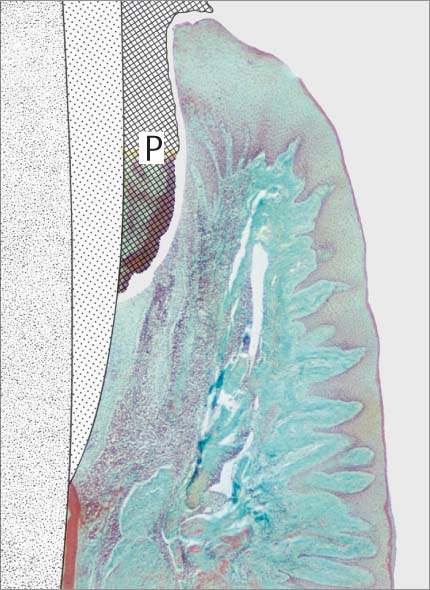

147 Moderate Gingivitis (left)

When gingivitis is clinically apparent (GI = 2, PBI = 2), the infiltrate becomes more dense and expansive. Collagen loss continues. The junctional epithelium proliferates laterally; a gingival pocket develops. P = subgingival plaque. (Masson stain, × 10)

148 Severe Gingivitis (right)

Pronounced edematous swelling (GI = 3, PBI = 3–4). The inflammatory infiltrate is expansive; collagen loss is pronounced. The junctional epithelium is transformed into a pocket epithelium (gingival pocket). Only in the apicalmost area are any remnants of intact junctional epithelium observed. Apical to the JE, the connective tissue attachment is intact (no loss of attachment; HE, × 10).

Clinical Symptoms

• Bleeding

• Erythema

• Edematous and hyperplastic swelling

• Ulceration

The earliest clinical symptom of an established lesion is bleeding subsequent to careful sulcus probing. This hemorrhage is elicited by the penetration of the probe tip through the disintegrating junctional epithelium and into the highly vascular sub-epithelial connective tissue. At this stage of the inflammatory process (PBI = 1), no gingival erythema may be visible clinically. Clinical symptoms of advanced (established) gingivitis include profuse bleeding after sulcus probing, obvious erythema and simultaneous edematous swelling. In the most severe cases, spontaneous bleeding and eventually ulceration may occur. The chronic types (and severities) do not elicit pain; pain occurs only in acute gingivitis (e. g., NUG, p. 85).

Even severe gingivitis may never progress to periodontitis. With proper treatment, gingivitis is reversible.

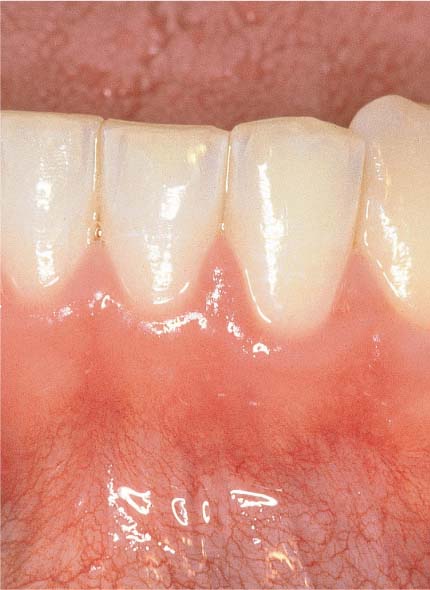

149 Healthy Gingiva (left)

The gingiva is pale salmon-pink in color, and stippled. The narrow free gingival margin is distinguishable from the attached gingival. After gentle probing with a blunt periodontal probe, no bleeding occurs.

150 Mild Gingivitis (right)

The localized erythema is scarcely visible, and one observes slight edematous swelling. Some of the former stippling is lost, and there is minimal bleeding upon probing.

151 Moderate Gingivitis (left)

Obvious erythema and edematous swelling. No stippling is apparent, and there is hemorrhage following probing of the sulcus.

152 Severe Gingivitis (right)

Fiery redness, edematous and hyperplastic swelling; complete absence of any stippling; interdental ulceration, copious bleeding on probing, and spontaneous hemorrhage.

Mild Gingivitis

A 23-year-old female came to the dentist for a routine check-up. She had no complaints and was not aware of any gingival problems, although in her medical history she indicated that her gingiva bled occasionally during tooth brushing. Her oral hygiene was relatively good. She had received tooth brushing instructions from a dentist once, but no subsequent OHI. The patient was not on a regular recall schedule. Calculus removal had been performed sporadically in the past during routine dental check-ups, and several restorations placed.

Findings:

| API | (Approximal Plaque Index): 30% |

| PBI | (Papilla Bleeding Index): 1.5 |

| PD | (Probing depths): ca. 1.5 mm maxilla, ca. 3 mm mandible |

| TM | (tooth mobility): 0 |

Diagnosis: Gingivitis in initial stage

Therapy: Motivation, OHI, plaque and calculus removal

Recall: Prophylaxis at 6-month intervals

Prognosis: Very good

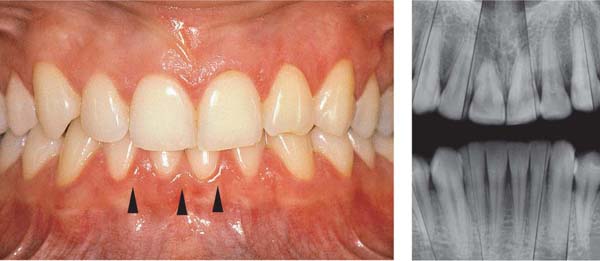

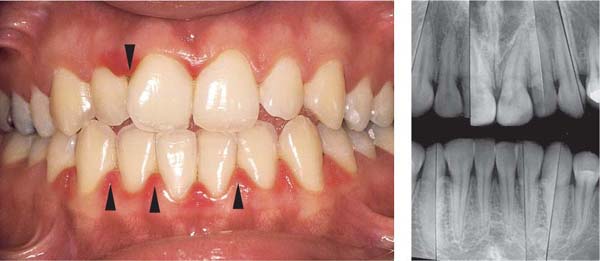

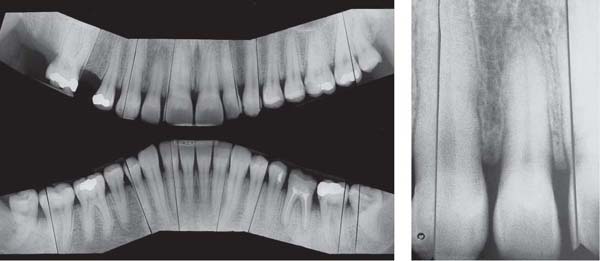

153 Mild Gingivitis in the Anterior Area

In the maxilla, one observes no overt signs of gingivitis, except for a mild erythema.

In the mandible, especially in the papillary areas, slight edematous swelling and erythema can be detected (arrows).

Right: Radiographically there is no evidence of loss of interdental bone height. The maxillary central incisors exhibit short roots.

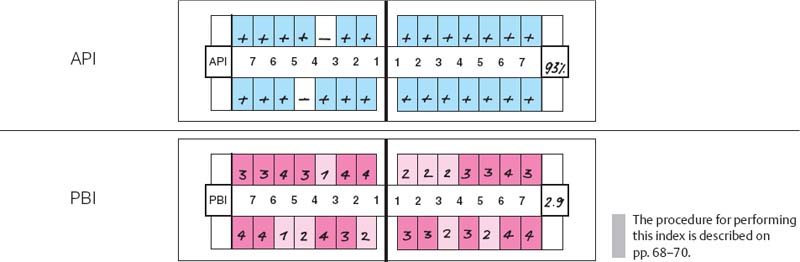

154 Papilla Bleeding Index (PBI)

After gentle probing of the sulci with a blunt periodontal probe, hemorrhage of grades 1 and 2 occurs. This is a cardinal sign of gingivitis.

155 Stained Plaque

Around the necks of the teeth and in interdental areas, small plaque accumulations are visible.

Right: Gingival vascular plexus (X) in the region of the junctional epithelium in a case of mild gingivitis. Above the white arrows, one observes the most marginal vascular loops in the area of the adjacent oral sulcular epithelium (OSE; canine preparation).

Courtesy J. Egelberg

Moderate Gingivitis

A 28-year-old female presented with a chief complaint of gingival bleeding. She “brushes her teeth,” but had never received any oral hygiene instruction from a dentist or hygienist. Calculus had been removed only infrequently, and a professional debridement had never been systematically performed. Generalized crowding of the teeth in both arches is evident, combined with an anterior open bite. These anomalies reduced any self-cleansing effects and made oral hygiene difficult. This also likely increased the severity of gingivitis.

Findings:

| API: 50% | PD: ca. 3 mm maxilla, ca. 4 mm mandible |

| PBI: maxilla 2.6, mandible 3.4. TM: 0 maxilla, 1 mandible | |

Diagnosis: Maxilla, moderate gingivitis; mandibular anterior region, severe gingivitis with pseudopockets.

Therapy: Motivation, oral hygiene, plaque and calculus removal; after re-evaluation, possible gingivoplasty.

Recall: Every six months initially.

Prognosis: With patient cooperation and compliance, very good.

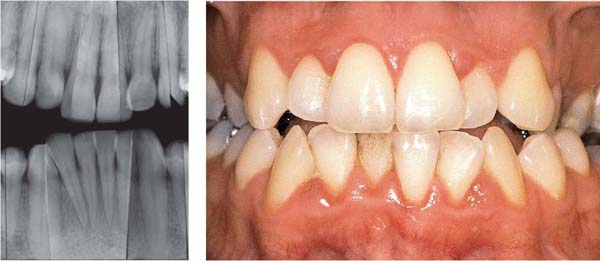

156 Moderate Gingivitis in Anterior Segments

Erythema and swelling of the gingiva. The symptoms are more pronounced in the mandible than in the maxilla.

Left: Radiographically there is no evidence of destruction (demineralization) of the interdental bony septa.

157 Papilla Bleeding Index (PBI)

The pronounced gingivitis that is particularly obvious in the mandibular anterior area is corroborated by the PBI. Bleeding scores of 2 and 3 are recorded after “sweeping” the sulcus with a periodontal probe in the papillary regions.

158 Stained Plaque

Moderate plaque accumulation in the maxilla. In the mandible, heavier plaque, especially at the gingival margins.

Left: Vascular plexus of the gingiva near the junctional epithelium in a case of severe gingivitis (Fig. 155, right)

Courtesy J. Egelberg

Severe Gingivitis

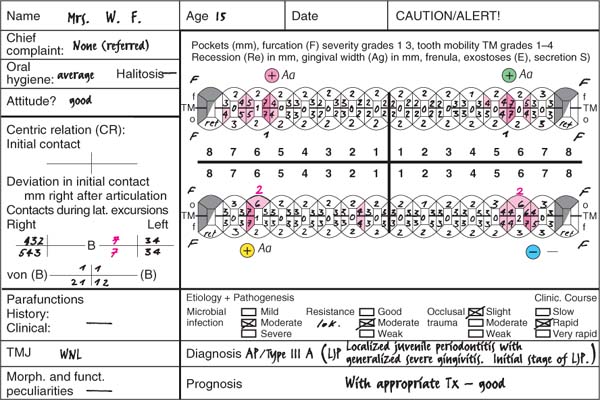

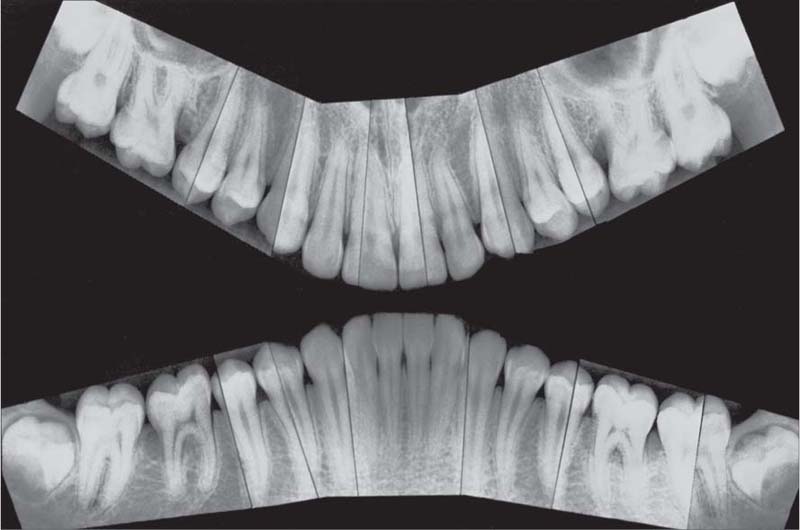

A 15-year-old male was referred for evaluation and treatment of suspected juvenile periodontitis (LJP/Type III A). The extremely pronounced gingivitis was, however, inconsistent with this diagnosis. Sulcus probing and radiographic examination revealed no attachment loss on anterior teeth or molars.

The patient practiced virtually no oral hygiene, stating that it was impossible to brush his teeth because the gingiva bled at the slightest touch. He had never received adequate motivation, nor any oral hygiene instruction, nor any treatment for his gingivitis.

Findings:

| API: 88% | PD: pseudopockets to 5 mm |

| PBI: 3.5 | TM: 0 |

Diagnosis: Severe gingivitis with edematous hyperplastic enlargement of the facial aspect of the anterior area; mouth breathing as possible etiologic co-factor (?).

Therapy: Motivation, oral hygiene instruction, definitive debridement. After re-evaluation, possible gingivoplasty.

Recall: Initially every three months.

Prognosis: With patient cooperation and compliance, good.

159 Severe Gingivitis

The clinical symptoms of severe gingivitis including erythema, edema and hyperplastic enlargement, are observed. The anterior region is more severely affected (slight crowding, mouth breathing?). Probing reveals no attachment loss; the base of the pseudopockets are not apical to the cementoenamel junction.

Right: Radiographically, one observes no evidence of bone loss on the interdental septa.

160 Papilla Bleeding Index (PBI)

Copious bleeding (PBI grade 4) occurs after sweeping the anterior sextant pseudopockets with a blunt periodontal probe. The inflammation is less pronounced in the premolar and molar regions.

If gingival hyperplasia is severe, the clinician must exclude other possible etiologic factors such as medicament-induced lesions and systemic disorders.

161 Stained Plaque

Moderately heavy accumulation of supragingival plaque. Not visible is the expanse of the subgingival plaque within pseudopockets. The pronounced inflammation, especially in the anterior region, anticipates significant plaque accumulation subgingivally.

Right: The papilla between 21 and 22 is grossly enlarged, erythematous and devoid of any stippling.

Ulcerative Gingivitis/Periodontitis

NUG/P = Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis/Periodontitis, Type V A (NUG) and V B (NUP)

Ulcerative gingivitis is usually an acute, painful, rapidly progressing inflammation of the gingiva, which may enter a sub-acute or chronic stage. Without treatment, this disease usually develops quickly into localized ulcerative periodontitis. It seldom occurs as a generalized process, nor is its severity always identical. It may be quite advanced in anterior segments, while the premolars or molars are not affected at all, or only mildly so. The reasons for this remain unknown (oral hygiene? ischemia? locally predominating pathogenic bacteria? plaque-retentive areas? tooth type?). Probing depths are usually shallow because gingival tissue is lost to necrosis as attachment loss proceeds. Secondary ulceration of other oral mucosal surfaces is rarely observed, and only in severe cases (AAP 1996e). Caution: Ulceration can represent an early oral symptom in HIV-positive patients and AIDS victims (p. 151).

Ulcerative gingivitis/periodontitis has become less common in recent decades than earlier (exception: HIV-positive and AIDS patients). In the younger population, the morbidity has been variously reported between 0.1–1 %.

The etiology of NUG is not completely understood. In addition to plaque and a previously existing gingivitis, the following local and systemic predisposing factors are suspected:

| Local Factors

• Poor oral hygiene • Predominance of spirochetes, fusiforms and P. intermedia, and occasionally Selenomonas and Porphyromonas in the plaque • Smoking (local irritation by tar products) |

Systemic Factors

• Poor general health, psychic stress, alcohol

• Smoking: nicotine as a sympatheticomimetic, and carbon monoxide (CO) as a chemotaxin (p. 216)

• Age (15–30 years)

• Season of the year (September/October and December/January; Skâch et al. 1970)

NUG/P patients usually exhibit similar life styles and habits: The teeth do not occupy a high position in the patient’s consciousness. They are usually young adults, heavy smokers (tobacco: high content of tar and nicotine), exercise poor oral hygiene, and become interested in treatment only during acute, painful exacerbations.

The clinical course is acute, but fever occurs only seldom. Within only a few days, interdental papillae may be lost to ulceration. The acute phase may gravitate into a chronic interval stage if host resistance improves (see pre-disposing factors) or through self-treatment (rinsing with a disinfectant mouthwash). Untreated ulcerative gingivitis exhibits a high recurrence rate, and may develop rapidly into ulcerative periodontitis (attachment loss with shallow pockets!).

Therapy: In addition to local debridement, the early stages of treatment should be supported with medicaments. Topical application of ointments containing cortisone or antibiotics, or metronidazol may be effective. In severe cases, systemic metronidazol (e. g., Flagyl) may be prescribed (see Medicaments, p. 287). After reduction of the acute symptoms in advanced cases, surgery to correct gingival contours may be indicated.

Histopathology

The clinical and histopathologic pictures in NUG are correlated. The histopathology of NUG is, however, significantly different from that of simple gingivitis.

As a consequence of the acute reaction, an enormous number of PMNs transmigrate the junctional epithelium in the direction of the sulcus and the col. In contrast to the situation in simple gingivitis, PMNs also migrate toward the oral epithelium and the tips of papillae, which undergo necrotic destruction. The ulcerated wound is covered by a clinically visible, whitish pseudomembrane that consists of bacteria, dead leukocytes and epithelial cells as well as fibrin. The tissue subjacent to the ulcerated areas is edematous, hyperemic and heavily infiltrated by PMNs. In long-standing disease, the deeper tissue regions will also contain lymphocytes and plasma cells. Within the infiltrated area, collagen destruction progress rapidly.

Spirochetes and other bacteria often penetrate into the damaged tissues (Listgarten 1965, Listgarten & Lewis 1967).

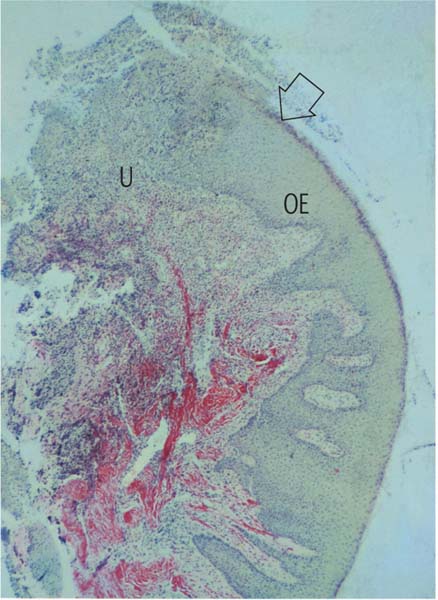

162 Papilla Biopsy

Affected papilla excised from a patient with mild ulcerative gingivitis, resembling the clinical situation in Fig. 164. The tip of the papilla and the tissue approaching the col have been destroyed by ulceration (U).

The oral epithelium (OE, stained yellow) remains essentially intact. In the deeper layers of the biopsy, one observes the red-stained intact collagen, while beneath the decimated papilla tip the collagen is largely obliterated (van Gieson, × 10).

The arrow indicates the section that is enlarged in Fig. 163.

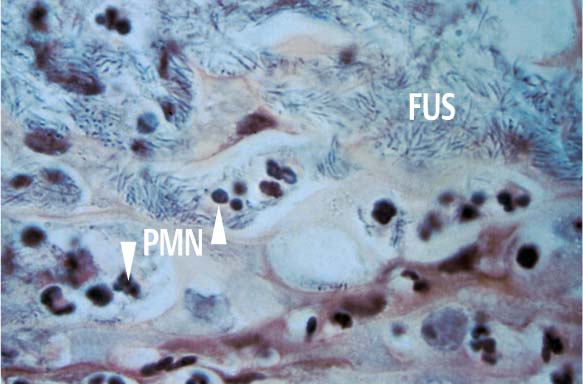

163 Surface of the Disintegrated Tissue

The upper portion of the figure exhibits thickly packed fusiform bacteria (FUS). Spirochetes present in the section are not visible with this staining technique, but the numerous PMNs are obvious. The brownish structures with weakly staining nuclei are dying epithelial cells (van Gieson, × 1000).

Clinical Symptoms—Bacteriology

• Necrotic destruction of the gingiva, ulceration

• Pain

• Halitosis

• Specific bacteria

Beginning in the tissues of the interdental col, there is necrotic destruction of papilla tips, followed by destruction of entire papillae and even portions of the marginal gingiva. It is not clear whether gingival destruction is caused primarily by vascular infarction or by invasion of bacteria into the tissues. In rare instances, depressed ulcerations may also be seen on the cheeks, lips or tongue. In the absence of treatment, the osseous portion of the periodontal supporting apparatus can also become involved. The earliest clinical symptom of ulcerative gingivitis is localized pain.

The patient with NUG is characterized by a typical, insipid, sweetish halitosis.

Generalized ulcerative gingivitis must be differentiated from acute herpetic gingivostomatitis (p. 131), which is generally accompanied by fever.

164 Earliest Symptom of NUG (left)

The most coronal portion of the papilla tip is destroyed by necrosis from the col outward. The defects are covered by a typical whitish pseudomembrane. The first pain may be experienced even before any ulcerations become visible clinically. NUG should be diagnosed and treated in this early, reversible stage!

165 Advanced Stage of Ulceration (right)

166 Complete Destruction of the Papilla (left)

Between the premolars there is no visible lesion, but areas of early necrosis can be seen on the mesial and marginal aspects of the canine. Note the complete destruction of the papilla between canine and first premolar.

167 Acute Recurrence (right)

The papillae have been completely destroyed. The previous acute stage has led to reverse architecture of the gingival margin. Beginning ulcerative periodontitis.

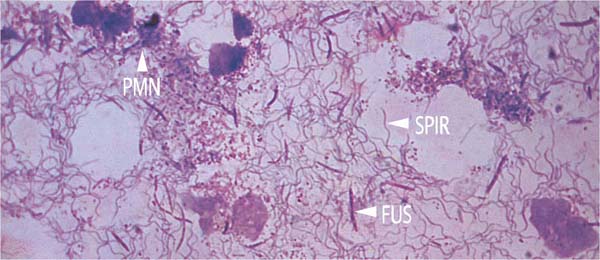

168 Bacteriology—Smear of the Pseudomembrane

In addition to dead cells, granulocytes (PMN) and fusiform bacteria (FUS), enormous numbers of spirochetes (SPIR) are visible (van Gieson, × 1000)

Ulcerative Gingivitis (NUG)

A 19-year-old female experienced gingival pain and hemorrhage for three days.

Findings:

| API: | 70% |

| PBI: | Anterior segments, 3.2 Premolar and molar regions, 2.6 |

| PD: | 2–3 mm proximal |

| TM: | 0–1 |

Diagnosis: Acute ulcerative gingivitis, early stage; NUG, Type V A.

Therapy: At the first appointment, careful mechanical debridement; topical medicaments: antibiotic or cortisone-containing ointment, metronidazol gel (e. g., Elyzol, p. 292). The patient may be instructed to rinse at home with mild hydrogen perborate solution.

Subsequent appointments: Motivation, repeated oral hygiene instruction, plaque and calculus removal.

Recall: Short-interval (information! plaque control).

Prognosis: With treatment and patient compliance, good.

169 Initial Stage

Initial acute ulcerative destruction of several papilla tips (arrows). Other papillae exhibit signs of mild inflammation, but no destruction.

Right: Radiographically one observes no evidence of resorption of interdental septal bone.

170 Initial Destruction of Papilla Tips in the Maxilla

Necrosis of the papilla tips between central and lateral incisors is apparent, with erythema and swelling. Note the initial necrosis of the papilla tips between the lateral incisor and canine. Between the central incisors, one notes erythema of the papilla, but not yet any signs of necrosis. If the patient experiences pain when this area is probed gently, it is evidence that the necrotic process has already begun in the col area.

171 Destruction of Papilla Tips in the Mandible

Each papilla exhibits signs of incipient ulceration, and each is already covered by a pseudomembrane consisting of fibrin, dead tissue cells, leukocytes and bacteria.

Ulcerative Periodontitis (NUP)

Ulcerative periodontitis always develops—often very rapidly—from a preexisting ulcerative gingivitis. Probing depths may be shallow because the destruction of tissue occurs simultaneously with the attachment loss. While the clinical signs associated with NUG can be eliminated by proper treatment, ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) always leads to irreversible damage (attachment loss, bone loss). Acute and subacute phases occur cyclically. Acute phases are always accompanied by pain, in contrast to simple gingivitis. Ulcerative periodontitis is seldom generalized.

Therapy: Similar to the case with ulcerative gingivitis, in the acute phase of NUP careful and complete plaque and calculus removal should be performed. This mechanical therapy can be supported by topical medicaments. After the pain subsides, systematic instrumentation (debridement) follows. In advanced cases, minor surgical procedures may be necessary after all acute symptoms subside: In mild cases, gingivoplasty; in advanced cases, contouring flap surgery. A strict recall program is absolutely necessary, because NUP has a tendency toward recurrence.

Acute Stage

172 Ulcerative Gingivoperiodontitis—Second Acute Episode

This 26-year-old male experienced a second, pronounced acute episode. In addition to gingivitis, in the maxillary anterior and molar segments attachment loss has occurred. (Treatment: p. 90)

Left: Expansive, painful mucosal ulcer adjacent to tooth 18. Extraction of tooth 18 is indicated following the acute episode.

Interval Stage

173 Localized Ulcerative Periodontitis

This 22-year-old male had experienced two acute episodes, which were not treated professionally. In this interval stage, the patient is free of pain.

Left: Advanced but very localized attachment loss in the anterior segment of the mandible. The interdental crater presents a niche for plaque accumulation, which can lead to exacerbation if host response is compromised.

174 Expansive, Generalized Ulcerative Periodontitis

This 30-year-old male complained of gingival recession. He had experienced pain in recent years, but did not seek treatment.

The now pain-free lesions have progressed to various degrees; interval stage (HIV-patient).

Left: In the anterior region of the mandible, especially between teeth 41 and 42, the attachment loss has progressed significantly.

Ulcerative Gingivoperiodontitis—Therapy

A 26-year-old male (see also Fig. 172) who was systemically healthy, presented complaining of severe pain and “inflamed gingiva.” A similar inflammation had occurred one year previously, but it resolved after the use of mouthwashes, without treatment by a dentist. The patient smoked ca. 40 cigarettes per day.

Findings:

| API: 80% | PBI: 3.2 |

| PD: 3–5 mm | TM: 0–1 |

| Second acute phase (one year later) | |

Diagnosis: Generalized, acute ulcerative gingivoperiodontitis.

Therapy: In acute stages, careful supragingival cleaning, chlorhexidine rinses; “slow release” medicaments (e. g., metronidazol: Elyzol gel) may be used if pockets are present. After the acute symptoms subside, systematic supra- and subgingival plaque and calculus removal. Surgical intervention (gingivoplasty) was indicated in this case, but was not performed.

Recall: Not desired by the patient.

Prognosis: Questionable; patient non-compliance.

175 Ulcerative Gingivoperiodontitis in a 26-year-old patient

Note the gingival destruction, especially in the papillary regions of the anterior teeth, gingival swelling, bleeding on probing and spontaneous hemorrhage, with heavy plaque accumulation.

One year previously, at about the same time of the year (December), identical symptoms had occurred.

Right: Detail of the gingival condition around tooth 22.

176 Clinical View Six Days Later

During two appointments (on day 1 and day 4), the teeth were carefully debrided (the supportive medicinal treatment is described in the text). The acute symptoms subsided to such a degree that a comprehensive scaling and root planing could be performed.

Right: Detail tooth 22.

177 Final Clinical Result

After repeated and systematic supra- and subgingival scaling (no surgical procedures) the NUG/NUP “healed” completely. The gingiva remains somewhat “puffy”; a gingivoplasty would be indicated. The patient “felt good” again, and refused any additional therapy, a reaction that is typical for such patients.

Right: Final clinical appearance; detail of tooth 22.

Hormonally Modulated Gingivitis

Types I A 2 a

Changes in the body’s hormonal balance generally do not cause gingival inflammation, but can increase the severity of an already existing plaque-induced gingivitis. In addition to insulin deficiency (Diabetes mellitus; pp. 132, 215), it is primarily the female sex hormones that often are associated with the progression of plaque-elicited gingivitis:

|

• Puberty gingivitis • Pregnancy gingivitis • Gingivitis from the “Pill” (rare) • Gingivitis menstrualis and intermenstrualis • Gingivitis climacterica |

Puberty Gingivitis

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that gingival inflammation during puberty is somewhat more pronounced when compared to the years preceding and following puberty (Curilovi ć et al. 1997, Koivuniemi et al. 1980, Stamm 1986). If oral hygiene is poor and/or if the adolescent is a mouth breather, a typical gingival hyperplasia may ensue, especially in the maxillary anterior area (Figs. 178 and 179). Therapy: Oral hygiene instruction, plaque and calculus removal; gingivoplasty if the hyperplasia is severe. Mouth breathing may require consultation with an appropriate medical specialist (ENT).

Pregnancy Gingivitis

This condition is not observed in every pregnant woman. Even if oral hygiene is good, however, the gingivae will exhibit an elevated tendency to bleed (Silness & Löe 1964). Therapy: Oral hygiene; recall every one to two months until breast-feeding is discontinued.

“Pill” Gingivitis

Gingival reaction to oral contraceptives is rare today (Pankhurst et al. 1981). Symptoms: Slight bleeding, rarely erythema or swelling.

Therapy: Oral hygiene.

Gingivitis menstrualis/Intermenstrualis

This gingival condition is exceedingly rare. Desquamation of gingival epithelium occurs during the twenty-eight day menstrual cycle, similar to vaginal epithelium. In exceptional cases, the desquamation can be so pronounced that a diagnosis of “discreet” gingivitis may be made, even less frequently gingivitis menstrualis or intermenstrualis (Mühle-mann 1952).

Therapy: Good oral hygiene to prevent secondary plaque-associated gingivitis.

Gingivitis climacterica

This alteration of the mucosa is also rare. The pathologic alterations are observed less on the marginal gingiva than on the attached gingiva and oral mucosa, which may appear dry and smooth, with salmon-pink spots. Stippling disappears and keratinization is lost. Patients complain of xerostomia and a burning sensation.

Therapy: Careful oral hygiene (pain!), and topical vitamin A-containing ointments and dentifrices. In severe cases, the gynecologist may elect to intervene by means of systemic estrogen supplements.

The following pages depict puberty gingivitis and pregnancy gingivitis.

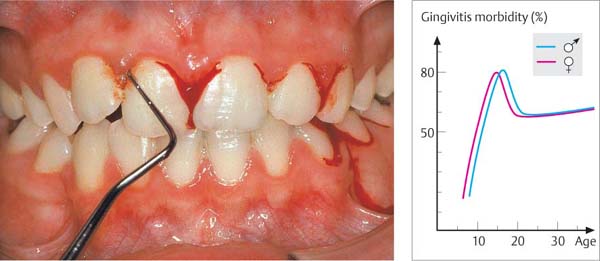

178 Puberty Gingivitis

In this 13-year-old female, more or less severe hemorrhage occurred after gentle sulcus probing. Plaque and mouth breathing were causes of the gingival inflammation. The pubertal hormonal surge may have been a cofactor.

Right: Morbidity of gingivitis in 10,000 persons. A peak is observed during puberty (Stamm 1986).

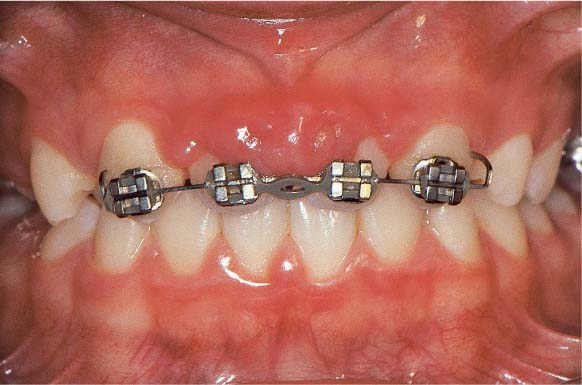

179 Puberty Gingivitis, Orthodontic Treatment

This 13-year-old male lost his maxillary central incisors due to an accident. Gingivitis, possibly puberty-related, was present before the accident.

Orthodontic means were used to move the lateral incisors mesially. In the absence of adequate plaque control, a severe inflammatory hyperplasia occurred between the maxillary lateral incisors.

Pregnancy

180 Mild Pregnancy Gingivitis

In this 28-year-old female, who was in her seventh month of pregnancy, a cursory inspection did not reveal symptoms of gingivitis in the anterior region. In the pre-molar and molar areas, however, a moderate gingivitis was detected.

Right: Copious hemorrhage occurred immediately after probing in the area of a defective restoration (plaque niche).

181 Severe Pregnancy Gingivitis

This 30-year-old patient exhibited moderate gingivitis even before her pregnancy. This photograph, taken during the eighth month, reveals severe inflammation and pronounced hyperplastic, epulis-like gingival alterations in the anterior segment.

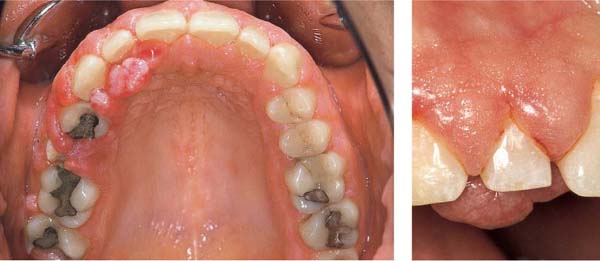

Severe Pregnancy Gingivitis—Gravid Epulis

This 24-year-old woman was eight months pregnant. She presented complaining that she “bites the swollen gums” on the left side of her mouth (gravid epulis). A severe, generalized gingivitis was also in evidence.

Findings:

| API: 70% | PD: 7 mm in the region of teeth 34 and 35, otherwise up to 4 mm (pseudopockets) |

| PBI: 3.2 | TM: 0–1 |

Diagnosis: Severe generalized pregnancy gingivitis with a large pyogenic granuloma (epulis) near teeth 34–35.

Therapy: During the pregnancy, repeated oral hygiene instruction, motivation, plaque and calculus removal; gingivoplasty (electrosurgery, laser) around teeth 34 and 35. After breast-feeding is terminated, re-evaluation and further treatment planning.

Recall: Frequency depends on patient compliance.

Prognosis: With treatment, good.

182 Severe Pregnancy Gingivitis

Due to poor oral hygiene, a pronounced gingivitis developed during the last half of the pregnancy. A large epulis is observed buccally and lingually around the mandibular premolars.

Left: The histologic section (of gingiva, not the epulis; see black line) exhibits normal oral epithelium, a relatively mild inflammatory infiltrate and widely dilated vessels (HE, x40)

183 Gravid Epulis

The surface of the epulis is ulcerated because the patient’s maxillary teeth bit into the tissue during mastication. For this reason, the redundant tissue had to be removed while the patient was still pregnant. Considerable hemorrhage may be expected during such surgery (laser, electro-surgery).

Left: The radiograph depicts some horizontal loss of the crestal compact bone of the interdental septa (demineralization).

184 Three Months After Gingivoplasty; Two Months Post-Partum

Definitive periodontal therapy and treatment planning for restorative work that is sorely needed should begin at this time (e. g., replacement of the old amalgam restorations with inlays or composites).

Pregnancy Gingivitis and Phenytoin

Some systemic medications, in combination with microbial plaque, can elicit gingival overgrowth. This adverse effect is best known for phenytoin (diphenylhydantoin, p. 121), which has been used for decades in the treatment of most types of seizure disorders.

Phenytoin is also often prescribed following skull trauma and neurosurgical procedures, so that relatively many persons (up to 1 % of the population?) take the drug at some time during life.

It is also well known that phenytoin can cause teratogenic damage, and therefore must never be taken during pregnancy. In the case depicted here, neither the patient nor her treating physician were aware of this potential side effect. The 22-year-old epileptic had taken phenytoin for many years, including during the first seven months of her pregnancy. She developed prominent gingival overgrowth, which was particularly pronounced in the maxillary right quadrant. Probing depths up to 7 mm (pseudopockets) were associated with copious hemorrhage (BOP). Fortunately, the child was born with no birth defects.

185 Phenytoin-Induced Gingival Overgrowth and Pregnancy Gingivitis

The epileptic patient is seven months pregnant. Up until the time of her dental visit, she was taking phenytoin. The gingivae exhibit generalized, pronounced inflammatory hyperplasia and overgrowth.

Right: Extreme gingival over-growth around tooth 12.

186 Radiographic Appearance

Despite the severe hyperplastic gingivitis, no bone loss is observed. Teeth 15 and 17 had already been extracted.

Right: Note normal interdental osseous septa even in the region around tooth 12, which exhibited pronounced, severe overgrowth.

187 After Periodontal Treatment

After the delivery, the patient underwent scaling, gingivoplasty and extraction of teeth 17, 15 and 28; this led to the reinstatement of healthy gingival relationships, although the phenytoin regimen had to be resumed.

Right: Even in the region where overgrowth was most severe (tooth 12), virtually healthy gingival relationships are observed.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis maintains its position as one of the most widespread diseases of mankind, but fortunately only ca. 5–10 % of all cases are aggressive, rapidly-progressing forms (Ahrens & Bublitz 1987, Miller et al. 1987, Miyazaki et al. 1991, Brown & Löe 1993, Papapanou 1996).

Periodontitis is a multifactorial disease of the tooth-supporting structures, elicited by a microbial biofilm (dental plaque). It usually develops from a pre-existing gingivitis; however, not every case of gingivitis develops into periodontitis. The quantity and virulence of microorganisms on the one hand, and host resistance factors (immune status, genetics and therefore heredity, as well as the presence of risk factors) on the other hand are the primary determinants for the initiation and progression of periodontal destruction (p. 21).

The classification of periodontitis evolves from dynamic, pathobiologic criteria, as recommended by the AAP (Armitage 1999; more extensive listing on p. 78; complete classification on p. 519):

| • Chronic Periodontitis | (Type II, formerly AP) |

| • Aggressive Periodontitis | (Type III, formerly EOP/RPP) |

| • Necrotizing Periodontitis | (Type V B/NUP, formerly ANUP) |

The two main forms (Types II and III) are further subclassified according to their expansion into localized (A: ≤ 30 % of all sites involved) or generalized (B: > 30 % of all sites involved).

Similarly, the degree of severity—as determined by clinical attachment loss—is divided into mild (1–2 mm), moderate (3–4 mm) and severe (≥ 5 mm).

An entire group of periodontal diseases comprise the aggressive forms (Type III), which were previously referred to as PP (prepubertal periodontitis), LJP (localized juvenile periodontitis), and RPP (rapidly progressive periodontitis).

The pathobiologic nomenclature, i. e., the description of the clinical course of periodontitis, is presented on pages 98 and 99. One must, of course, keep in mind that a “practical” diagnosis for every patient, for every tooth, and for every site must be performed clinically and radiographically to assess the severity, i. e., the pathomorphology of the disease process.

In this chapter, the following aspects of periodontitis will be presented:

|

• Severity of periodontitis • Types of pockets • Morphology of bone loss • Furcation invasion |

• Histopathology • Clinical and radiographic symptoms • Clinical cases depicting the various forms of periodontitis |

Pathobiology—The Most Important Forms of Periodontitis

The pathobiological nomenclature for the various forms of periodontitis is not a rigid, definitive classification. Today, one differentiates between chronic and aggressive forms of the disease, which may be localized or generalized (pp. 519–522). The chronic form of the disease may transform into an aggressive form, e. g., in the elderly, where the immune system is less effective. Most types of periodontitis progress in a step-wise fashion (random burst theory). Stages of exacerbation alternate with stages of remission.

As science continually provides new knowledge concerning microbiology as well as pathogenesis—especially the host response to the infection—the diagnosis and the nomenclature can no longer simply be defined according to the clinical course of the disease; it is now possible to characterize periodontitis as an Aa– or a Pg-associated disease (etc.). In the future, it may become even more important to characterize the diverse parameters of the host immune response, the mediators and the risk factors; these are ultimately responsible for the existence of the disease and the speed of its progression.

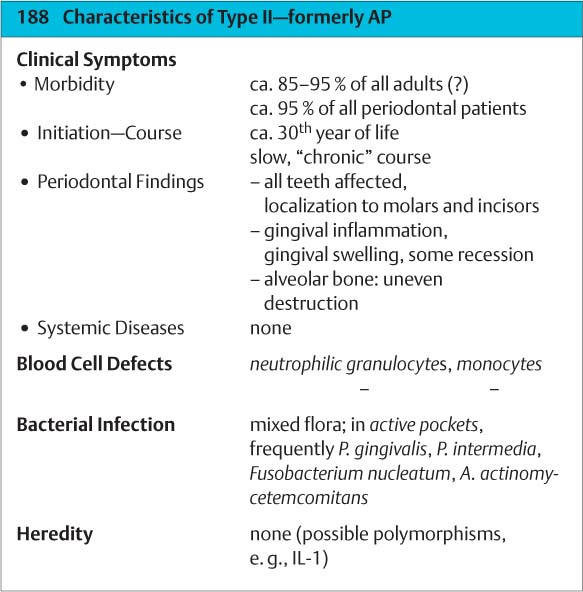

Type II

(Chronic Periodontitis; formerly AP)

This most common form of periodontitis begins between the ages of 30 and 40 years, generally from a pre-existing gingivitis. The entire dentition may be equally affected (generalized, Type II B). More often, however, the distribution of the disease is irregular, with more severe destruction primarily in molar areas but secondarily also in anterior segments (localized; Type II A). The gingivae exhibit varying degrees of inflammation, with “shrinkage” in some areas and fibrotic manifestations elsewhere.

Exacerbations occur at rather lengthy intervals. Risk factors (e. g., heavy smoking, IL-1-positive genotype) can accentuate the clinical course. In the elderly, the disease can lead to tooth loss, which may also be due to a decrease in host immune response and more frequent acute stages.

Therapy: Chronic periodontitis can be successfully treated by means of purely mechanical therapy, even if the patient’s cooperation/compliance is not optimum.

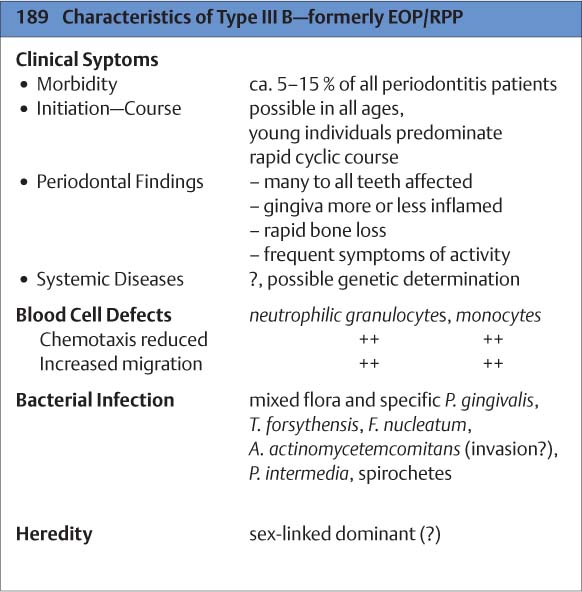

Type III B

(Aggressive Periodontitis; formerly EOP/RPP)

Aggressive forms of periodontitis are relatively rare (Page et al. 1983a, Miyazaki et al. 1993, Lindhe et al. 1997, Armitage 1999). They are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 30 years. Females appear to be more frequently affected than males. The severity and distribution of attachment loss vary considerably. One observes infrequent acute stages, which may transition into chronic disease. The cause of the active stages is specific microorganisms (Aa, Pg etc.), which may actually invade the ulcerated tissues. Risk factors (smoking, systemic disease such as diabetes, conditions of psychic tension and stress) and pro-inflammatory mediators that reduce the immune response can amplify the disease picture.

Therapy: The majority of aggressive cases can be successfully treated by means of purely mechanical therapy. In severe cases, a supportive systemic antibiotic regimen may be indicated.

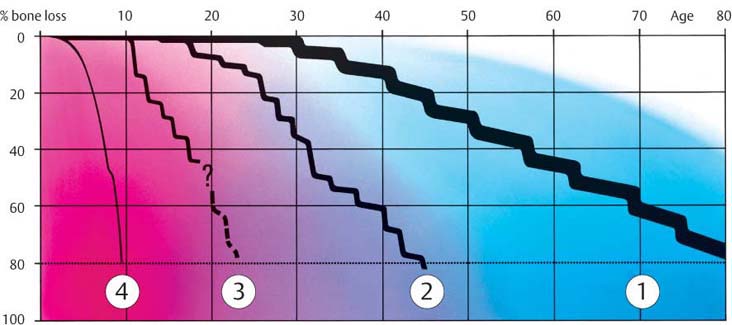

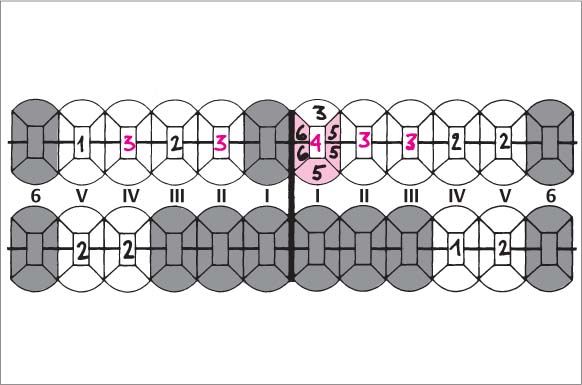

190 Forms of Periodontitis

| 1 | Chronic, slowly progressive periodontitis in adults—Type II |

| 2 | Aggressive, rapidly progressing periodontitis—Type III B |

| 3 | Aggressive, localized (juvenile) periodontitis—Type III A |

| 4 | Aggressive, generalized, prepubertal, rapidly progressing periodontitis—Type IV B |

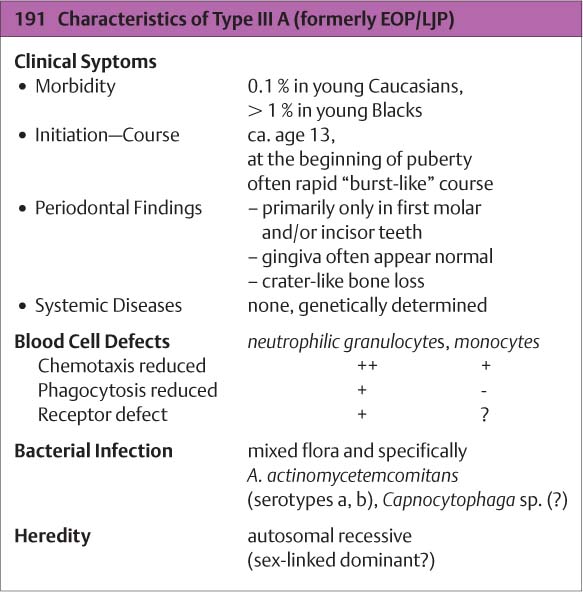

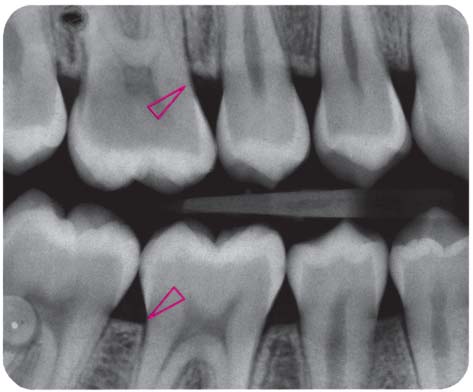

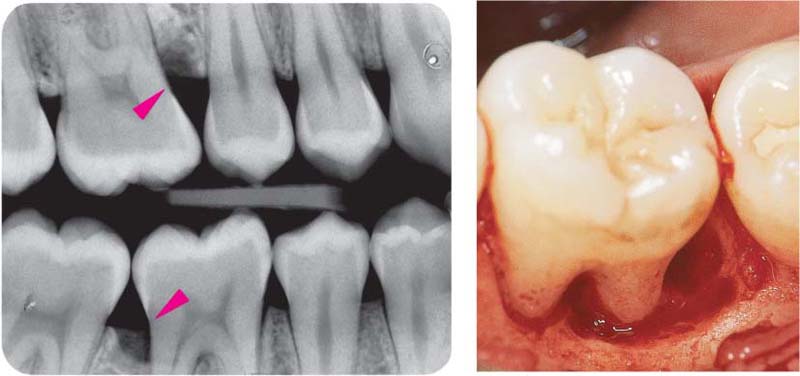

Type III A

(Aggressive Periodontitis, formerly EOP/LJP)

This rare disorder occurs early and attacks the permanent dentition. It begins in puberty, but is usually not diagnosed until several years later, often when lesions are discovered serendipitously (e. g., on bitewing radiographs taken for caries assessment). In the initial stages, incisors and/or first molars are affected in both maxilla and mandible; later, other teeth may also be affected. Hereditary factors (genetics, ethnic origin) have been demonstrated. Girls are affected more frequently than boys. In the early stages of aggressive periodontitis, one seldom observes pronounced gingivitis. The gingival pockets almost always (90 %) harbor Aa. The patient’s serum contains immunoglobulins against Aa leukotoxins, which damage PMNs.

Therapy: With early diagnosis and therapy consisting of vigorous mechanical debridement and supportive systemic administration of medicaments, the destructive process can be halted rather easily. Osseous defects may eventually regenerate.

Type IV B

(Aggressive Periodontitis; formerly EOP/PP)

This extraordinarily rare form of periodontitis may be detected even upon eruption of the deciduous teeth and is usually associated with genetic aberrations and systemic disorders (Page et al. 1983b, Tonetti & Mombelli 1999, Armitage 1999; cf. p. 118). The disease progresses rapidly and is usually generalized:

|

• A localized form begins at ca. age 4 and exhibits only mild gingival inflammation with relatively little plaque. • The generalized form (Type IV B) begins immediately after eruption of the deciduous teeth. It is associated with severe gingivitis and gingival shrinkage. The microbiology remains unclear. |

Therapy: The localized form can be halted by a combination of mechanical therapy and systemic antibiotics. The generalized form appears to be refractory to therapy.

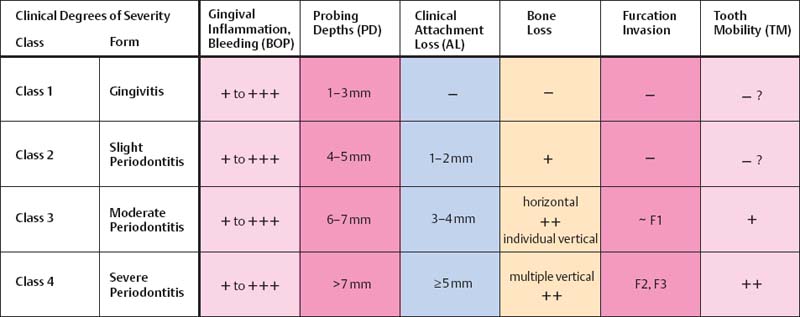

Pathomorphology—Clinical Degree of Severity

Periodontitis is a general term. As already described, it subsumes pathobiologically dynamic forms of disease progressing at varying rates, and exhibits differing microbial etiologies and varying influences by the host immune response (p. 21). It may sound trite, but one must understand that all forms of periodontitis begin at some point in time. They develop at various times during a patient’s life, usually from a pre-existing plaque-elicited gingivitis. In the absence of treatment, the disease progresses, albeit at varying rates. It is therefore clear that during clinical data collection, which leads to the diagnosis for an individual case, not only must the type of disease be ascertained, it is also necessary to determine in what pathomorphologic stage the disease process currently exists or, in other words, how far atta–chment loss has progressed. From these diagnostic criteria, clinical course, expanse (localized, e. g., less than 30 % of all sites, or generalized) and clinical degree of severity, the practitioner can derive a prognosis and estimate the degree of difficulty of the necessary treatment, which will naturally be higher for aggressive periodontitis (Type III) than for a similarly advanced chronic periodontitis (Type II).

Case Diagnosis—Single-Tooth Diagnosis—“Sites”

While it is usually possible to diagnosis the type of periodontitis for the entire dentition, it is rather a more difficult matter to precisely define the clinical degree of severity. Periodontitis almost always progresses at different rates in different areas of the mouth, on different teeth, and even at different sites on individual teeth. Therefore, any statement about “average” disease severity is usually meaningless. The following pathomorphologic classification (degree of severity) cannot be understood as pertinent to the individual case (patient); it relates more to single tooth diagnosis as well as single tooth prognosis. The reasons for the often quite irregular localized destruction are not always clear (oral hygiene, plaque-retentive niches, localized specific bacteria, tooth type, function?). In addition to describing gingivitis, practitioners will continue to use the terms mild, moderate and severe to differentiate the stages of periodontitis. It is perhaps important to remember that different authors, “schools,” and periodontologic societies use various synonyms for these different clinical manifestations of disease.

Clinical Degrees of Severity

| • mild/slight | … levis | … superficialis |

| • moderate | … media | … media |

| • severe/advanced | … gravis | … profunda |

Most recently, the AAP (1996c) has defined the degree of severity of periodontitis not exclusively according to probing depths and terms such as mild, moderate or severe; rather more consideration is given also to gingival inflammation, bone loss, attachment loss, furcation invasion and tooth mobility.

Conclusions

All of the pathomorphologic classifications of periodontitis presented on this page (cf. AAP Glossary 2001) attempt to describe the severity of the disease as it exists immediately after clinical examination; these descriptors say very little about the pathobiology, the dynamics or the speed of progression of periodontitis (prognosis).

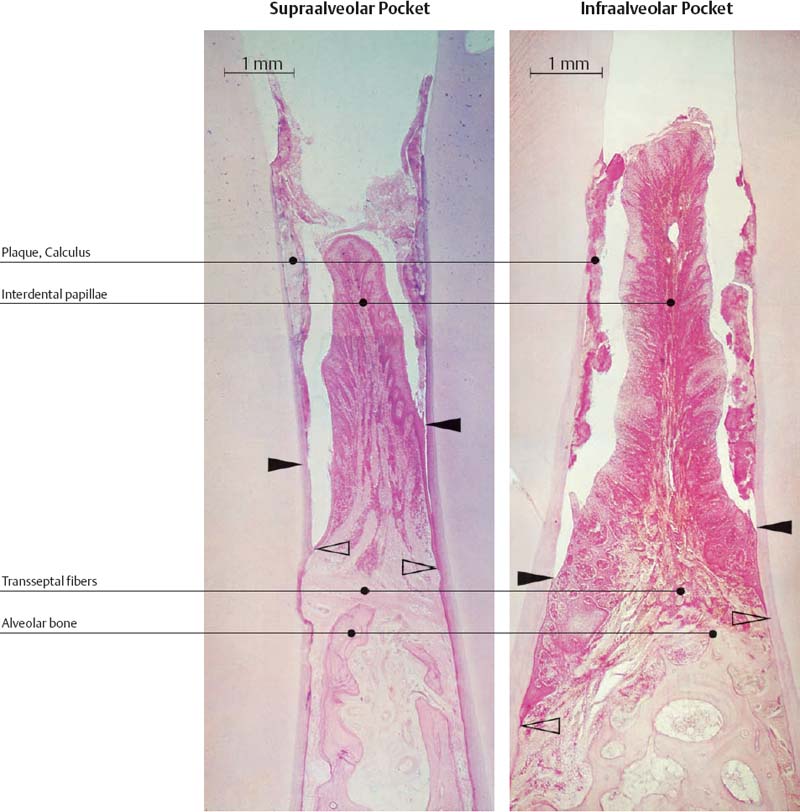

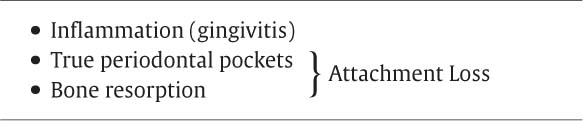

Pockets and Loss of Attachment

Pocket formation without any loss of connective tissue attachment is seen in gingivitis in the form of the gingival pocket and the pseudopocket (p. 79). A true periodontal pocket will exhibit attachment loss, apical migration of the junctional epithelium, and transformation of the junctional epithelium into a pocket epithelium (Müller-Glauser & Schroeder 1982). The true periodontal pocket may assume two forms (Papapanou & Tonetti 2000):

• Suprabony pockets, resulting from horizontal loss of bone

• Infrabony pockets, resulting from vertical, angular bone loss. In such cases the deepest portion of the pocket is located apical to the alveolar crest.

Whether pocket development is horizontal or vertical appears to be due to the thickness of the interdental septum or the facial and oral bony plates.

True loss of attachment results from microbial plaque and the metabolic products of plaque microorganisms. The range and effective radius of destruction is ca. 1.5–2.5 mm (Tal 1984; Fig. 195).

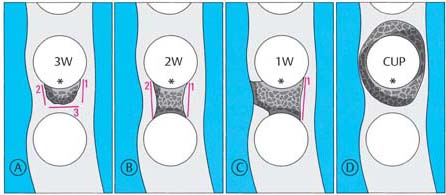

193 Types of Periodontal Pockets

A Normal Sulcus

The apical termination of the junctional epithelium (JE) is at the cementoenamel junction (open arrow).

B Suprabony Pocket (red)

Attachment loss; proliferation of pocket epithelium. A remnant of junctional epithelium (pink) persists at the base of the pocket.

C Infrabony Pocket

Bony pocket

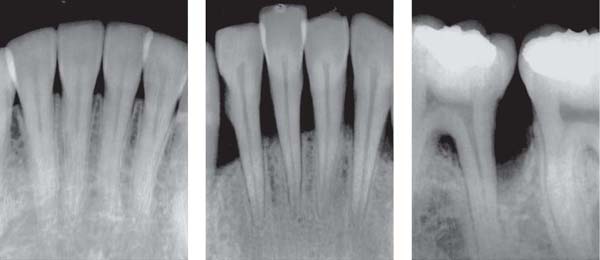

194 Types of Bone Loss

No attachment loss (left)

Normal alveolar septa. Lamina dura and alveolar crest remain intact.

Horizontal Bone Loss (middle)

Up to 50 % loss of interdental septal bone.

Vertical Bone Loss, Furcation Involvement (right)

Severe bone loss distal to the first molar. The furcation of this tooth is also involved.

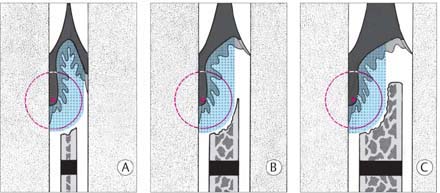

195 “Range” of Destruction = Contour of Bone Resorption

The destructive process radiating from the plaque measures ca. 1.5–2.5 mm (red circle). The expanse (width) of the interdental septa therefore determines for the most part the type (morphology) of bone loss.

| A | Narrow: horizontal resorption |

| B | Average: horizontal resorption, incipient vertical resorption |

| C | Wide: vertical resorption, bony pocket |

Intra-alveolar Defects, Infrabony Pockets

The infrabony pocket (infra-alveolar vertical bone loss) may exhibit various forms in relation to the affected teeth (Goldman & Cohen1980, Papapanou & Tonetti 2000).

Classification of Bony Pockets

• Three-wall bony pockets are bordered by one tooth surface and three osseous surfaces

• Two-wall bony pockets (interdental craters) are bordered by two tooth surfaces and two osseous surfaces (one facial and one oral)

• One-wall bony pockets are bordered by two tooth surfaces, one osseous surface (facial or oral) and soft tissue

• Combined bony pockets (cup-shaped defects) may be bordered by several surfaces of a tooth and several of bone. The defect surrounds the tooth.

The causes for this wide variation in pocket morphology and resorption of bone are myriad and cannot always be wholly elucidated in each individual case.

196 Schematic Representation of Pocket Morphology

| A | Three-wall bony defect |

| B | Two-wall bony defect |

| C | One-wall bony defect |

| D | Combined bony defect, crater-like resorption (“cup”) |

The walls of each pocket are shown in red (1–3).

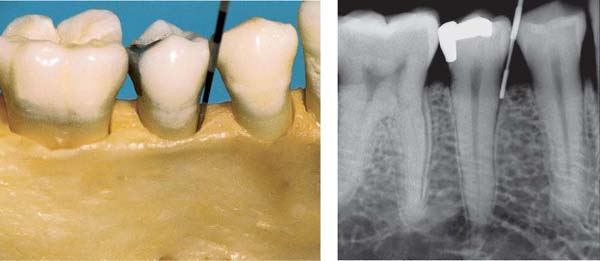

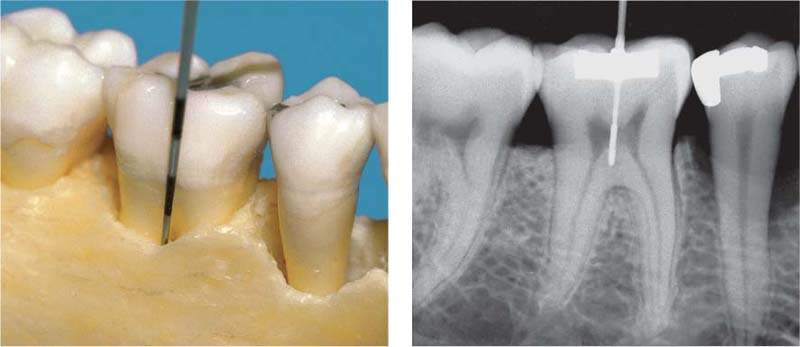

197 Small Three-Wall Defect

Early pocket formation on the mesial aspect of the second pre-molar. The color-coded probe (CP12) measures a depth of ca. 3 mm. If gingiva were present, the total probing depth would be ca. 5mm.

198 Deep Three-Wall Bony Pocket

The periodontal probe descends almost 6 mm (measured from the alveolar crest) to the base of this three-wall defect.

Mention was already made of the significance of bone thickness (Fig. 195). Since the bony septa between the roots become thinner coronally, the initial stage of periodontitis generally presents as horizontal resorption. The greater the distance between the roots of two teeth, the thicker will be the intervening septum, and the development of a vertical defect is more likely.

In addition to such simple osseous morphology, other factors almost certainly play some role in the type of resorption:

• local acute exacerbation elicited by specific bacteria in the pocket

• local inadequate oral hygiene (plaque)

• crowding and tipping of teeth (plaque-retentive areas)

• tooth morphology (root irregularities, furcations)

• improper loading due to functional disturbances (?).

The morphology of the bony pocket is of importance in both prognosis and treatment planning (defect selection). The amount of bone remaining will affect the chances of osseous regeneration after treatment.

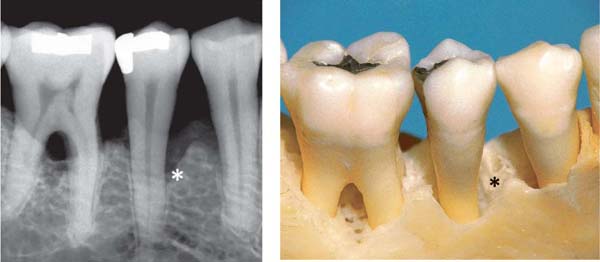

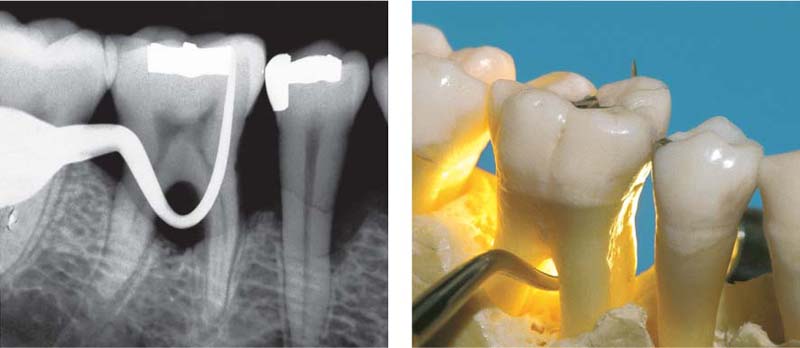

199 Two-Wall Bony Pocket, Interdental Crater

The coronal portion of this defect is bordered by only two bony walls (and two tooth surfaces). In the apical areas the two-wall defect becomes a three-wall defect (see left probe tip in the radiograph, left).

200 One-Wall Bony Pocket on the Mesial of Tooth 45

Advanced bone loss in premolar/molar area. On tooth 45, the facial wall of bone is reduced almost to the level of the mesial pocket (*). A portion of the lingual plate of bone remains intact. The facial root surface and the interdental spaces could be covered with soft tissue to the cementoenamel junction, masking the defect clinically.

201 Combined Pocket, Cup-Shaped Defect

In the region of tooth 45, the apical portion of the osseous defect courses around the tooth, creating a “moat” or “cup” (Goldman probe in situ). The bony pocket is therefore bordered by several osseous and several tooth surface walls.

Furcation Involvement

Periodontal bone loss around multirooted teeth presents a special problem when bi- or trifurcations are involved. Partially or completely open furcations tend to accumulate plaque (Schroeder & Scherle 1987). Exacerbations, abscesses, progressive loss of attachment and rapid deepening of periodontal pockets occur frequently, especially with through-and-through furcation involvement. In addition, open furcations are particularly susceptible to the development of dental caries.

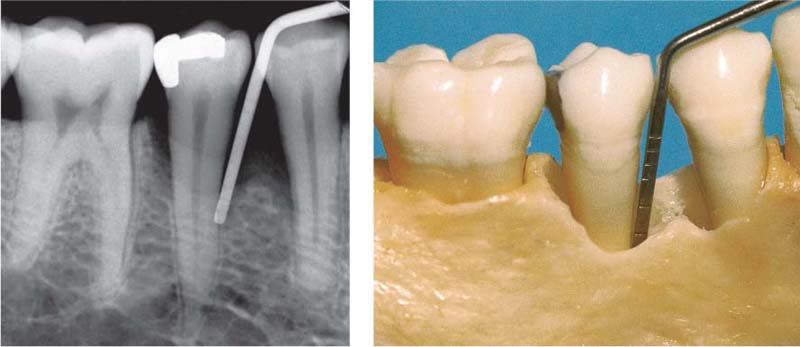

Modified from Hamp et al. (1975), three classes of horizontally measured furcation invasion are acknowledged:

Class—Horizontal

| Class F1: | The furcation can be probed in the horizontal direction up to 3 mm. |

| Class F2: | The furcation can be probed to a depth of more than 3 mm, but is not through-and-through. |

| Class F3: | The furcation is through-and-through and can be probed completely. |

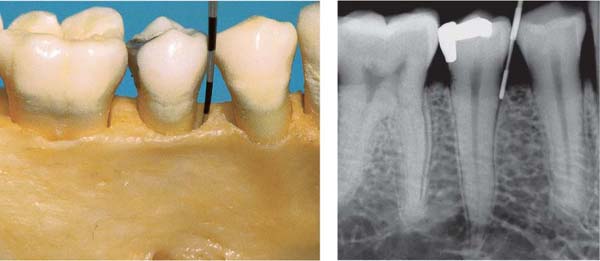

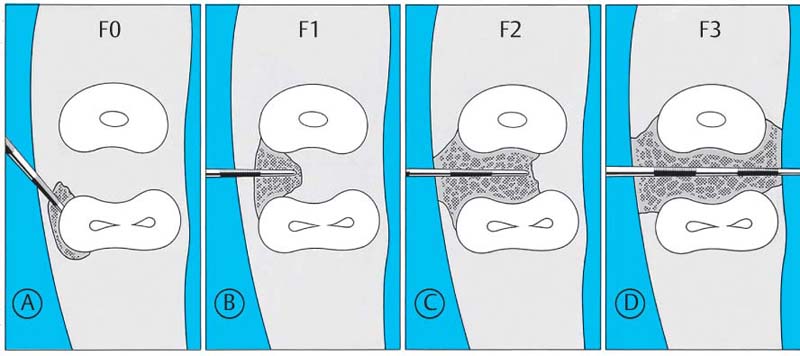

202 Classification of Furcation Involvement—Horizontal Measurement

Furcation involvement may be combined with infrabony pockets.

| A | F0: | Pocket on the mesial root, but without furcation involvement. |

| B | F1: | Furcation can be probed 3 mm horizontally. |

| C | F2: | Furcation can be probed deeper than 3 mm. |

| D | F3: | Through-and-through furcation involvement. |

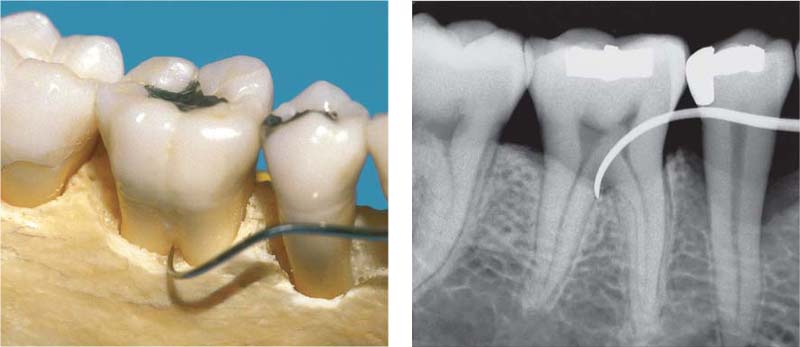

203 No Furcation Involvement—F0

In a clinical situation, in the region of the buccal furcation entrance, a ca. 5 mm deep suprabony pocket would be detectable.

204 Furcation Involvement—F1

Using a curved, pointed explorer (CH3; Hu-Friedy) the buccal furcation can be probed to a depth of less than 3 mm. Probing is performed from both buccal and lingual aspects. Special furcation probes are available on the market today. They are rounded and have millimeter indications; e. g. Nabers-2 (Hu-Freidy).

Vertical bone loss in a furcation can also be classified (subclasses A-C, Tarnow & Fletcher 1984). It is measured in millimeters from the roof of the furcation (see also pp. 172, 383):

Subclasses—Vertical

|

Subclass A: |

1–3 mm |

|

Subclass B: |

4–6 mm |

|

Subclass C: |

> 7 mm |

Therapy: Class F1 and F2 furcation involvement may be successfully treated by root planing alone or by flap procedures (conventional and regenerative). Class F3 furcations are usually treated by means of hemisection or by amputation of one root (p. 381).

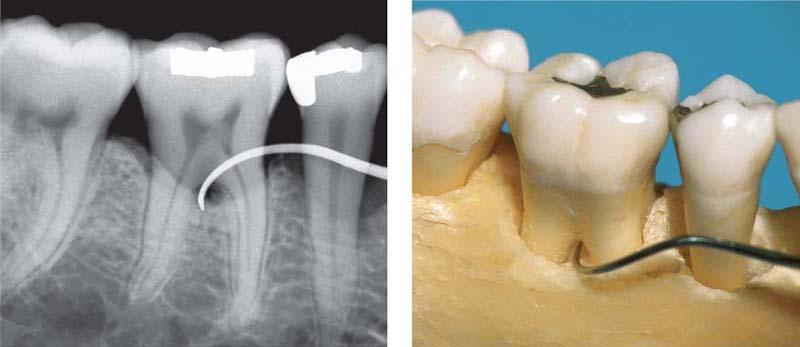

205 Furcation Involvement—F2

The explorer can probe more than 3 mm into the furcation, which is not yet through-and-through.

206 Furcation Involvement—F3, Mild, Subclass A

Narrow, through-and-through bifurcation involvement in the face of relatively minor bone loss (Nabers-2 probe).

Less than 3 mm of bone loss in the vertical dimension; this corresponds to subclass A.

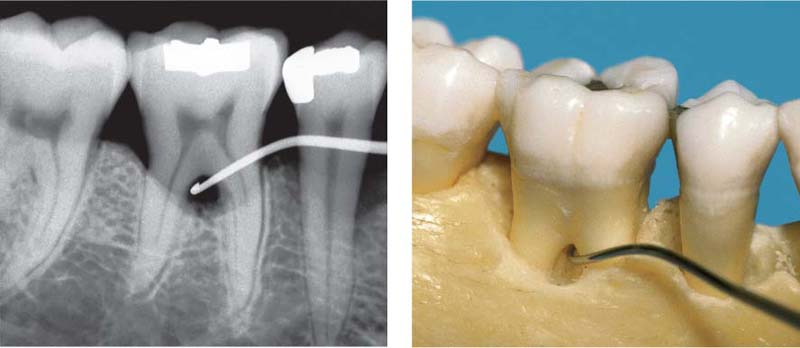

207 Furcation Involvement—F3, Severe, Subclass C

Wide, through-and-through bifurcation in a case exhibiting severe horizontal and vertical bone loss (Cowhorn explorer). The vertical extent of the furcation exceeds 6 mm: Subclass C.

Histopathology

The primary symptoms of periodontitis are attachment loss and pocket formation. Pocket epithelium exhibits the following features (modified from Müller-Glauser & Schroeder 1982):

• irregular boundary with the subjacent connective tissue, exhibiting rete pegs; toward the periodontal pocket, epithelium is often very thin and partially ulcerated

• in the apicalmost region, the pocket epithelium becomes a very narrow and short junctional epithelium

• transmigration of PMNs through the pocket epithelium

• defective basal lamina complex on the connective tissue aspect.

Within the subepithelial connective tissue, collagen is lost and numerous inflammatory cells invade. In acute stages, pus formation and microabscesses occur. Bone is resorbed, and deeper osseous marrow is transformed into fibrous connective tissue.

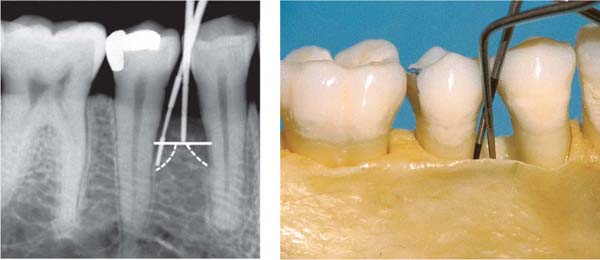

208 Suprabony Pocket, Gingival Pocket (left)

Pocket epithelium with distinct rete ridges. In the apicalmost region (between the arrows) one observes intact junctional epithelium (exhibiting artifactual separation from the tooth surface in this section). Subepithelial inflammatory infiltrate extends into the area of the transseptal fibers (HE, x40).

209 Infrabony Pocket (right)

Intact junctional epithelium (open arrow) persists on the tooth (left), apical to the inter-dental bony septum. The pocket epithelium displays pronounced rete ridges and areas of ulceration. Inflammatory infiltrate extends into the periodontal ligament and marrow (HE, x40).

Additional Clinical and Radiographic Symptoms

Primary Symptoms

These obligate primary symptoms of periodontitis must be present simultaneously for a diagnosis of “periodontitis” (= inflammation-induced attachment loss); they can occur in different forms and in measurable degrees of severity.

Additional Symptoms

The additional symptoms, listed below, are not obligate in every case of periodontitis, but they may modify or complicate the disease picture:

• Gingival shrinkage

• Gingival swelling

• Pocket activity: bleeding, exudate, pus

• Pocket abscess, furcation abscess

• Fistula

• Tooth migration, tipping, extrusion

• Tooth mobility

• Tooth loss

Gingival Shrinkage

During the course of periodontitis, especially the slowly progressive, chronic type in adults, gingival shrinkage may occur with time. Gingival shrinkage can also occur after spontaneous transition of an acute exacerbation into a chronic, quiescent stage, or following comprehensive periodontal therapy or after draining of abscesses. Whatever the cause, shrinkage leads to exposure of root surfaces.

This type of shrinkage must not be confused with true gingival recession, which can occur in the absence of clinical inflammation. True recession occurs without the formation of periodontal pockets and is most often observed on the facial aspect of roots. On the other hand, gingival shrinkage due to periodontitis may also be quite pronounced in the papillary regions.

If, as a result of shrinkage, the gingival margin is located apical to the cementoenamel junction, clinical probing of any pockets will underestimate the actual loss of attachment. True attachment loss must be measured from the cement-oenamel junction to the base of the pocket.

Gingival Swelling

Enlargement of the gingiva is a symptom of gingivitis that may remain if progression to periodontitis occurs.

If the gingivae are edematous or hyperplastically enlarged beyond the cementoenamel junction, pocket depth (probing depth) may be overestimated, while true attachment loss may be underestimated (Fig. 212).

Pocket Activity

The activity of a pocket and the frequency of active episodes are of more importance than absolute pocket depth in mm, especially in regard to treatment planning and prognosis. Bleeding on probing, presence of exudate, and suppuration after application of finger pressure are all signs that an active phase of periodontitis is in progress (Davenport et al. 1982). Such signs are often observed in the aggressive forms of periodontitis, but may also be seen in older patients with chronic periodontitis and reduced host immune response.

Pocket and Furcation Abscess

An additional symptom of active periodontitis is the pocket or furcation abscess. This develops during an acute exacerbation if necrotic tissue cannot be either resorbed or expelled (for example, due to closure of the coronal gingiva above deep pockets, furcations and retentive areas). An abscess (macronecrosis) may also be the consequence of injury, for example biting upon hard, sharp foodstuffs, improper oral hygiene efforts (e. g., a broken toothpick), or iatrogenic trauma. In rare instances a periodontal abscess can develop into a submucosal abscess (Parulis).

An abscess is one of the few manifestations of periodontitis that may elicit pain. If an abscess is expansive, extending to the apical region, the tooth may become sensitive to percussion. A painful abscess must be drained on an emergency basis, either by way of the pocket orifice itself or via incision through the lateral wall. An abscess may release spontaneously through a fistulous tract or via the gingival margin.

Fistula

A fistula may be the result of spontaneous opening of an abscess if the gingival margin is sealed. If the underlying cause (active pocket) is not eliminated, the fistula may persist for an extended period of time without any pain. The orifice of the fistula is not always located directly above the acute process; this can lead to improper diagnosis of the location of an abscess (probe the fistulous tract with a blunt probe!).

Shrinkage—Swelling

In advanced periodontitis, additional clinical symptoms include shrinkage (gingival recession) or swelling of the gingiva; tooth migration and tipping of individual teeth or groups of teeth can occur. The result of such tooth movements is the creation of diastemata, which can present an esthetic problem. There are many factors that could be responsible for tooth migration and it is not possible in every case to determine the specific cause. It is nevertheless clear that compromised tooth-supporting apparatus is a prerequisite for tooth migration, tipping etc. Numerous other factors may also play a role: missing antagonists, functional occlusal disturbances, oral parafunctions (lip biting, cheek biting, tongue thrust etc.).

A tooth exhibiting a deep pocket on one side and intact periodontal fiber structure on the other side may migrate not so much as a result of pressure exerted by granulation tissue in the pocket, as by forces deriving from the still intact collagenous supracrestal fiber bundles in the healthy tissues. The fact that migrated teeth usually exhibit their unilateral pocket on the side opposite the direction of wandering would appear to support this hypothesis.

The figures below present typical clinical measurements (probing depth, recession of the marginal gingiva, clinical attachment loss) (see also p. 171).

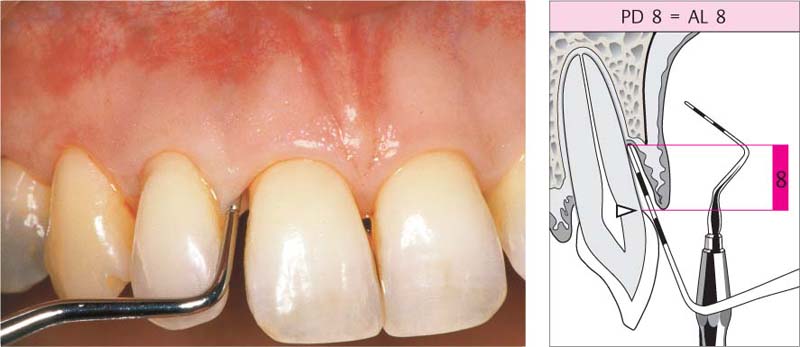

Clinical Attachment Loss

210 Pocket Measurement: Probing Depth (PD) = Attachment Loss (AL)

The measurement (8 mm) is made from the gingival margin, which in this case is still in its normal position near the cementoenamel junction; only in such cases does probing depth correspond identically to attachment loss.

Right: The schematic clearly depicts that the pocket depth corresponds to the attachment loss.

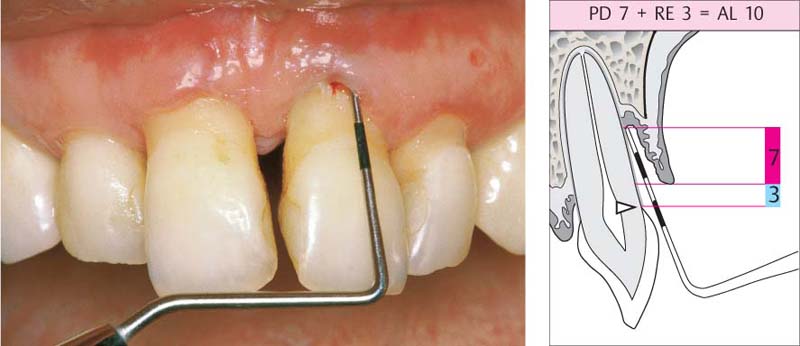

211 Pocket Measurement: Probing Depth Underestimates Attachment Loss

The measurement (7 mm) is made from the gingival margin, which is 3 mm apical to the cementoenamel junction. Thus, the true attachment loss is 10 mm.

Right: The schematic diagram reveals that the probing depth underestimates the attachment loss because of the recession (RE) of the gingival tissues.

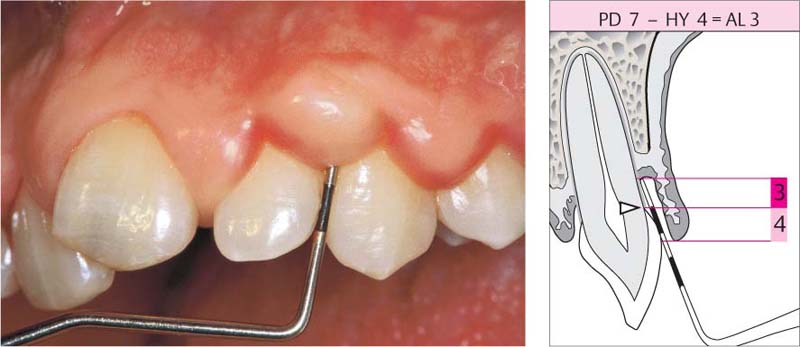

212 Pocket Measurement: Probing Depth Overestimates Attachment Loss

The measurement (7 mm) is made from the gingival margin, but the hyperplastic gingivae (HY) extend beyond the CEJ, creating a pseudopocket. The clinical attachment loss (AL) is 4 mm less than probing depth.

Right: The schematic diagram reveals that the attachment loss is overestimated as a result of the gingival swelling.

Pocket Activity, Tooth Migration and Tooth Mobility

Pocket activity and tooth mobility are symptoms of severe, advanced periodontitis. Elevated tooth mobility must, however, be interpreted carefully because it can be influenced by numerous factors.

Even in a healthy periodontium, the teeth exhibit physiologic differences in mobility depending on number of roots, root morphology and root length (p. 174).

Even in a healthy periodontium, occlusal trauma can lead to an increase in tooth mobility (p. 461). In cases of periodontitis, it is the quantitative loss of bone that is the primary determinant of tooth mobility, but superimposed occlusal trauma can increase tooth mobility still further. In such cases, one may observe a continuously increasing (progressive) tooth mobility, which is very unfavorable in terms of single tooth prognosis.

Tooth Loss

The final “symptom” of periodontitis, the one which ultimately stops the disease process, is tooth loss. It seldom occurs spontaneously because extremely mobile teeth that are no longer functional are usually extracted prior to spontaneous exfoliation.

213 Periodontal Fistula—Pus

13 mm pocket on the distal of tooth 11, which is a candidate for extraction. After probing, pus escapes from both the fistulous tract and the gingival margin.

Left: Pus exudes from an active pocket on tooth 11 after finger pressure is applied.

214 Periodontal Abscess

Originating from a 12 mm pocket on the mesial aspect of the tipped, vital tooth 47, an abscess has developed, which is just about to open spontaneously.

Left: The radiograph reveals a severe vertical bony defect on the mesial of tooth 47.

215 Tooth Migration and Tipping

Creation of a diastema by severe tipping of tooth 41 after loss of 42. Patient exhibits a heavy tongue thrust when swallowing.

Left: Tooth mobility. Increased tooth mobility can be caused by functional disturbances and/or by periodontal attachment loss. Mobility is measured clinically by using two instruments or one instrument and a fingernail (degrees of mobility, see p. 174).

Chronic Periodontitis—Mild to Moderate

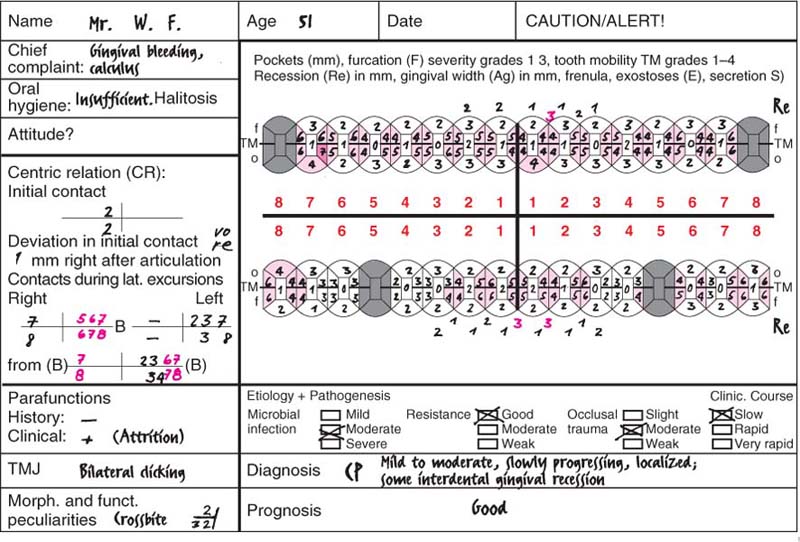

This 51-year-old male had received restorative dental care at irregular intervals. The dentist had never performed any periodontal diagnostic procedures, nor any therapy. The patient himself complained of occasional gingival bleeding and calculus that bothered him. He was unaware of any periodontal disease and felt that he was completely functional in mastication.

Findings: See charting and radiographic survey (p. 109).

Diagnosis: Slowly progressing, mild to moderate chronic periodontitis (Type II).

Therapy: Motivation, oral hygiene instruction and follow-up initial therapy. Closed scaling and root planing. After reevaluation, modified Widman procedure at several sites. No systemic therapy. Possible bridgework in mandibular posterior segments.

Recall: Every 4–6 months.

Prognosis: Even if the patient’s compliance is only average, the prognosis is good. In cases such as this, the dentist or periodontist is always “very successful.”

216 Clinical Overview (above)

A cursory inspection reveals only gingivitis and the absence of interdental papillae. The mandibular first molars were extracted 30 years previously, with resultant slow tooth migration, tipping and diastemata. Occlusion is poor.

217 Plaque Disclosure, Oral Hygiene (right)

The labial surfaces exhibit almost no plaque accumulation, while the interproximal areas are filled with plaque and calculus.

218 Mandible During the Flap Procedure

The facial crest of bone is somewhat bulbous but shows no signs of active destruction. Interdental 3 mm craters were detected.

Treatment consisted solely of root planing, minor recontouring of the bulbous bony margin (osteoplasty) and repositioning of the flaps at their origin position (no apical repositioning).

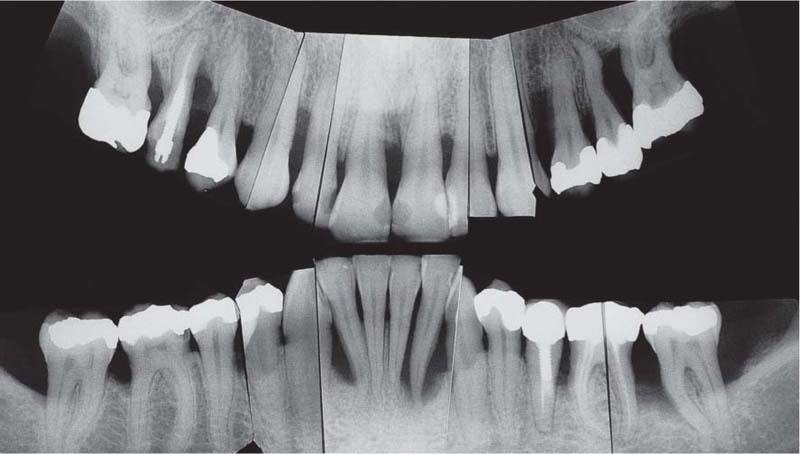

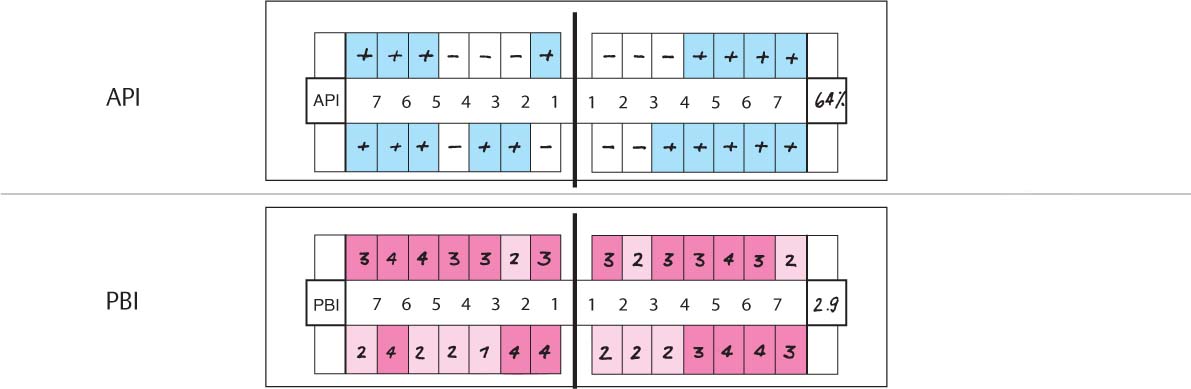

219 Aproximal Plaque Index (API) and Papilla Bleeding Index (PBI)

| API | 93%. Oral hygiene is poor. Almost all of the interdental spaces harbor plaque. |

| PBI | 2.9. The index is very high. All papillae bled during performance of the PBI. |

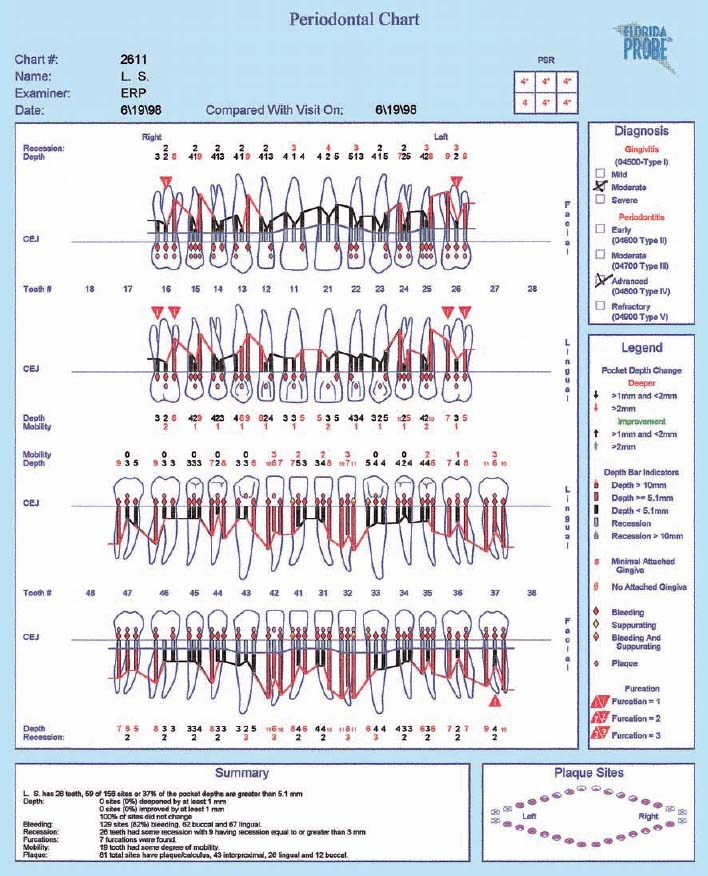

220 Periodontal Charting—I

This periodontal chart (description p. 194, Fig 439) is used in many dental offices, and has convenient places for recording probing depth, recession, furcation involvement and tooth mobility using numerical scores.

This case exhibits uniform probing depths throughout, especially in the interdental areas. For an assessment of the true attachment loss, the millimeter measurements entered by “Re” (recession) must be considered; these indicate the amount of gingival shrinkage.

Tooth mobility is low (grade 0–2). Functional analysis revealed premature contact between the upper and lower right lateral incisors (cross bite, increased mobility). Disturbances in lateral excursion and protrusion.

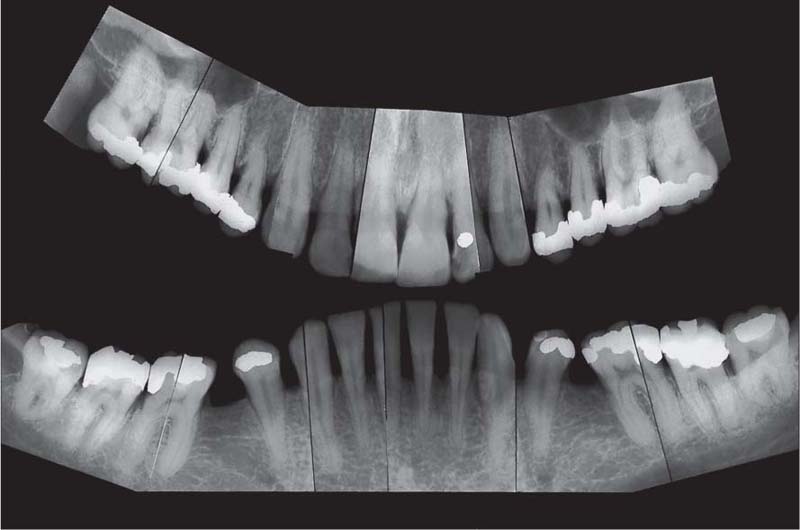

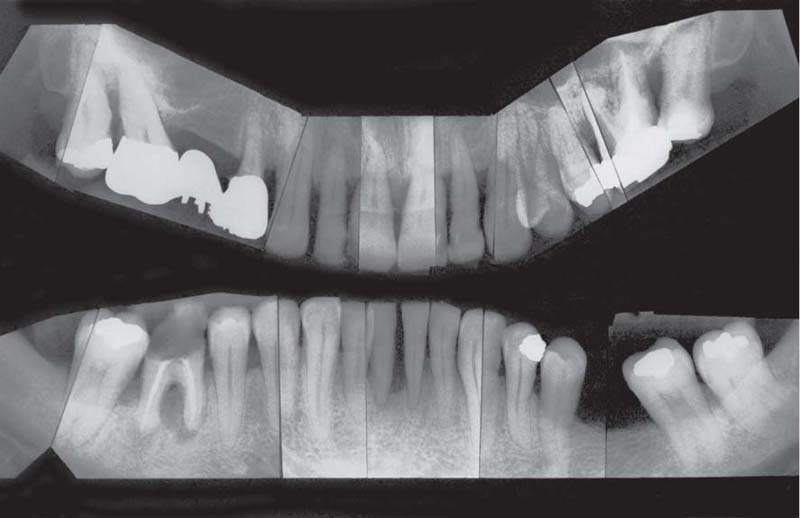

221 Radiographic Survey

The radiographs confirm the clinical observations: localized, mild to moderate, mainly horizontal bone loss.

Note migration and tipping of several teeth in the mandible. Some of the restorative work is inadequate.

Most important is that the “strategically” important canines and molars will be easy to restore (no furcation involvement).

(Note: This is not a “panoramic radiograph” in the usual sense of that term. Rather this survey was prepared by cutting and fitting individual periapical radiographs into a unified whole. This practice provides a more detailed overview of each individual segment of the dentition than any available panoramic film.

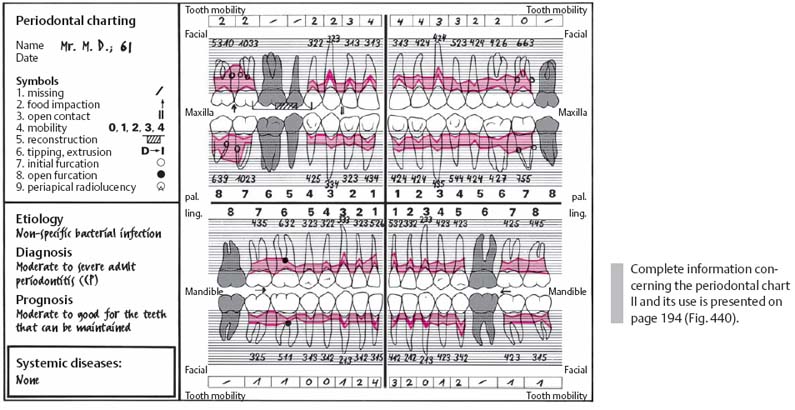

Chronic Periodontitis—Severe

For decades, this 61-year-old male patient had “scrubbed” his maxillary anterior teeth using a horizontal motion. He had never received oral hygiene instructions, and virtually all of other areas of his dentition were completely neglected. Restorations were inadequate.

Findings: See chart and radiographic survey (p. 111).

Diagnosis: Moderate to severe generalized chronic periodontitis (Type II B). The pronounced gingival shrinkage in the maxillary anterior sextant should not be confused with classical gingival recession!

Therapy:

• Immediate: Extraction of teeth 18, 17, 28 and 46 and the root of 41. The crown will be used as a temporary pontic by attaching it to the adjacent teeth (acid etch).

• Definitive treatment: Motivation, modification of oral hygiene, extraction of 26 and 31. Initial periodontal therapy (definitive debridement) and possible subsequent surgical procedures and a cast framework partial denture.

Recall: Every 4–6 months.

Prognosis: For the teeth to be maintained and treated periodontally, the prognosis is good.

222 Clinical Overview (above)

Noticeable in maxillary anterior region are the severe gingival shrinkage and the wedge-shaped defects (hard-bristle toothbrush, abrasive dentifrice). Periodontal pockets were “brushed away” by the patient!

223 Mandibular Anterior Probing Depths (right)

Probing of a 9 mm pocket on the mesial aspect of 41 provoked only slight bleeding. The cervical areas of the mandibular anterior teeth also exhibit abrasion.

224 Retained Root (Tooth 41)

Tooth 41 was no longer functional and had to be extracted. Its root, which had virtually no bony support remaining, was amputated and the natural crown was used as a temporary pontic during periodontal treatment, by bonding it to the adjacent teeth using the acid etch technique.

225 Plaque Index (PI) and Bleeding Index (BOP)

| PI | 69%. With the exception of the maxillary anterior and some facial surfaces in the mandibular anterior regions, plaque was present on almost all tooth surfaces. |

| BOP | 75% of the pockets examined bled after gentle probing. |

All teeth present were probed at all four surfaces (mesial, distal, facial and oral; p. 68–69).

226 Periodontal Charting—II

Using this modified “Michigan Chart,” gingival contour, probing depths and attachment loss are represented visually.

Probing depths around each tooth are measured first from the facial aspect at mesial, mid-buccal and distal sites, then from the lingual aspect at 3 similar sites. Because of the pronounced gingival recession, the pockets in the anterior area are not very deep, despite great attachment loss. All anterior teeth were highly mobile.

227 Radiographic Survery

The radiographs reveal a very typical, irregular distribution of bone resorption; this is commonly observed in older patients. While some teeth and/or some tooth surfaces have already lost all attachment, hardly any bone resorption is observed on the mandibular canines and the premolars.

At tooth 46, the apical and periodontal lesions appear to communicate.

Aggressive Periodontitis—Ethnic Contributions?

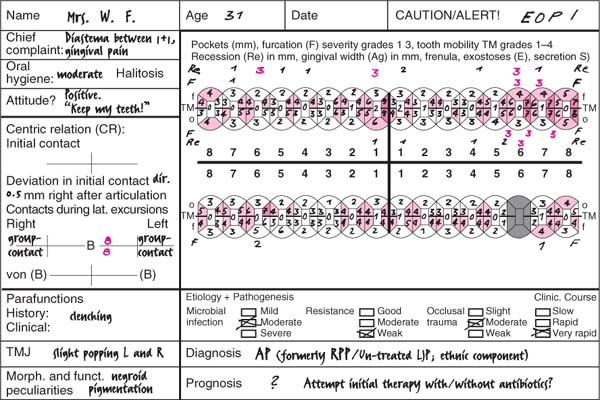

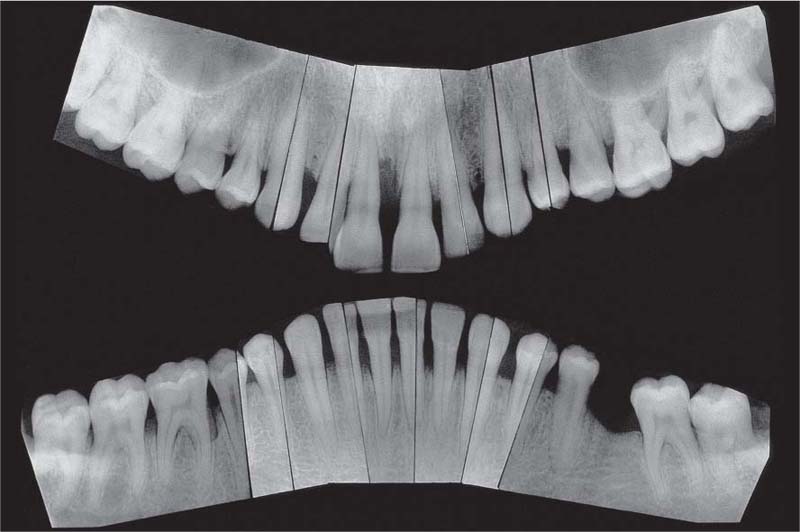

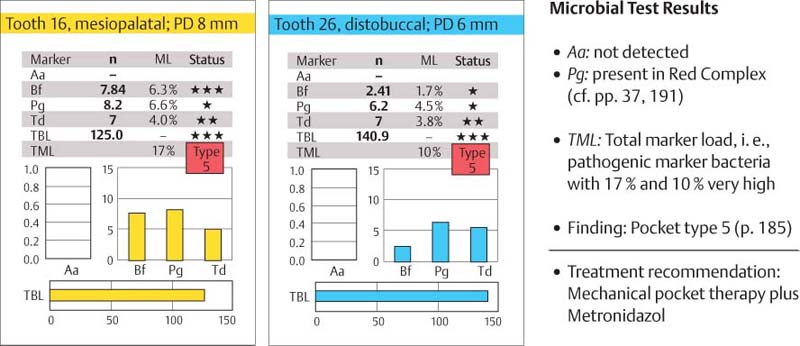

This 31-year-old female immigrated to Switzerland from Ethiopia ten years previously. She complained of loose teeth and the formation of a diastema between her maxillary central incisors. Hemorrhage occurred during tooth brushing. She had never undergone any periodontal treatment.

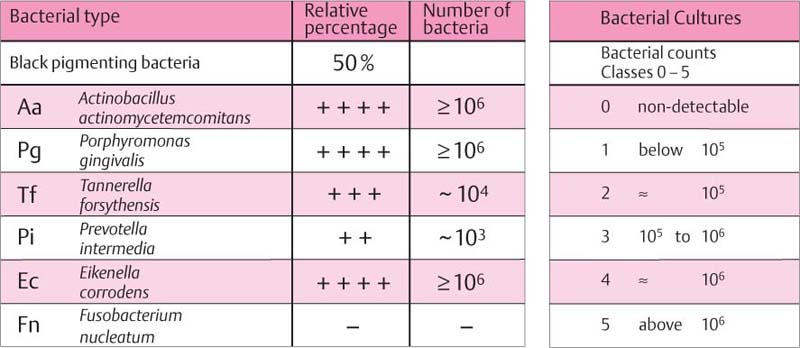

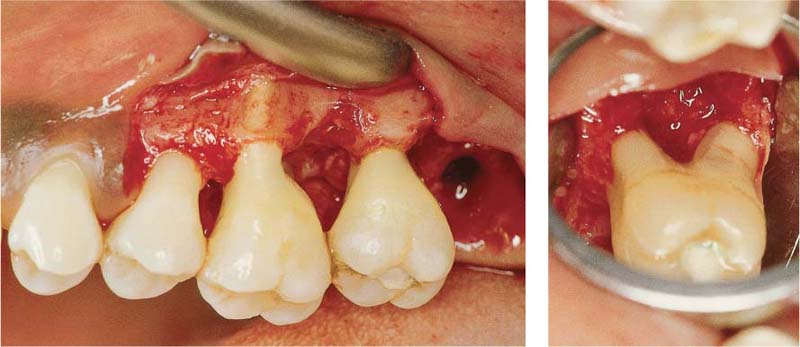

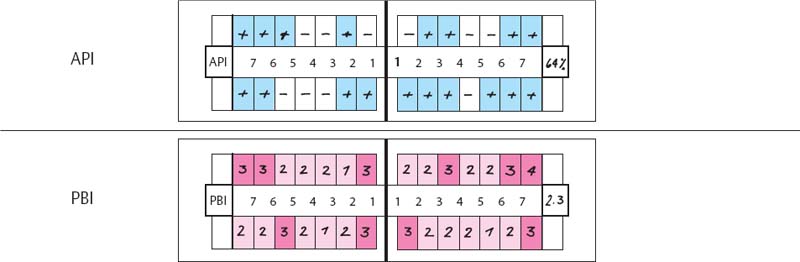

Findings: See microbiology (Fig. 229), charting and radiographs (p. 113).

Diagnosis: Aggressive, moderate periodontitis; an ethnic component must be considered.