Function—Functional Therapy

The masticatory system is composed of the jaws, the temporomandibular joints, the muscles of mastication, the nervous system, the teeth with their occlusal complexes, and the periodontal ligament. These components are physiologically and morphologically synchronized when function is normal. Within certain tolerance limits, the masticatory system can adapt to deviations from the norm (compensation, adaptation). However, if severe alterations or diseases occur in any one of the component parts of the masticatory system, the other components may also be affected (de-compensation or regressive adaptation; Bumann & Lotzmann 1999, Color Atlas of Dental Medicine: TMJ Disorders and Oro-facial Pain).

Functional disturbances do not elicit periodontitis! Nevertheless, such disturbances must be recognized and treated because they elicit alterations in masticatory musculature and temporomandibular joint function as well as excessive amounts of tooth abrasion, increased tooth mobility and the progression of any existing periodontitis (Ramfjord & Ash 1983). This chapter will present:

|

• Normal function – Physiologic tooth mobility • Disturbed function – Occlusal periodontal trauma • Therapy for functional disturbances: Bite guards |

Normal Function

The complexity of the stomatognathic system makes it difficult to define the term “normal function.” It is only possible to describe physiologic data and norms for the individual components:

Force

Normal chewing force is dependent on the type of food consumed. When eating pudding or puree etc., chewing force is quite low as measured in Newtons (1 Newton = 1 kg x m/s2= ca. 100 p), while chewing tough meat, ca. 150 N (ca. 15 kp); even with very hard foodstuffs, chewing force seldom exceeds 200 N (Ammann 1980).

Duration

The “normal” temporal loading of the periodontium is short. The occlusal forces that are imposed upon the periodontium during chewing and swallowing are intermittent in character. The duration of a chewing maneuver is only about 0.1 – 0.4 seconds. During swallowing (even of saliva) the periodontium is loaded for only ca. 1 second. If these maneuvers are summed over a 24-hour period, it is revealed that only 15–20 minutes of peak loading occurs per day (Graf 1969).

Direction

The “normal” direction of forces that are imposed upon the periodontium during chewing is extremely variable. The ideal direction of loading would be vertical/axial because this would ensure that all periodontal fibers and the alveolar process would be loaded evenly. Such equal loading does not occur even in centric occlusion. During chewing, on the other hand, alternating and combined forces are exerted primarily from the horizontal/orofacial and vertical directions (Graf et al. 1974, Graf & Geering 1977).

Physiologic Tooth Mobility

The “syndesmotic mechanism” by which the teeth are supported within their alveoli, and the elasticity of the entire alveolar process provide for a measurable physiologic tooth mobility in horizontal, vertical and rotational directions (Periodontometer, Mühlemann 1967; “Periotest,” Schulte et al. 1983).

Tooth mobility varies in daily as well as larger cycles (biorhythm): Teeth are more mobile in the morning than in the evening (Himmel et al. 1957). In addition, each type of tooth exhibits characteristic mobility depending upon the surface area available for insertion of periodontal ligament fibers into cementum, and also according to root number, root length and root diameter (Fig. 1130).

Increased Tooth Mobility

Elevated tooth mobility may result from occlusal trauma or quantitative bone loss due to periodontitis (Figs. 1131/1132). Increased tooth mobility alone is not a criterion of periodontal health or disease.

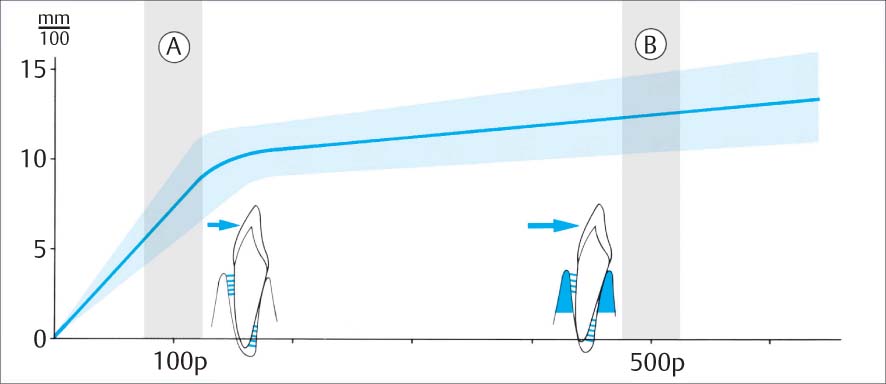

1129 Physiologic Tooth Mobility with Increasing Force

Force N = Newton, 1 N = ca. 100 p

A Initial Periodontal Tooth Mobility

Upon light loading in the orofacial direction with 1 N (ca. 100 p), only the collagen fibers of the periodontal ligament are stretched.

B Secondary Periodontal Tooth Mobility

Loading with 5 N (ca. 500 p), the entire alveolar process (blue) is elastically deformed.

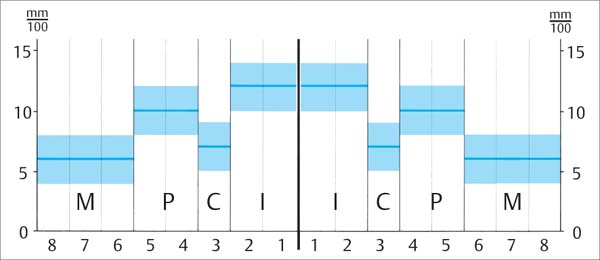

1130 Healthy Periodontium: Mean Values of Tooth Mobility for Various Tooth Types

The values depicted here represent mean mobility figures following application of a constant heavy force in the orofacial direction (5 N, periodontal tooth mobility). These values would be TM=0 in clinical charting (p. 174).

|

I |

Incisors |

|

C |

Canines |

|

P |

Premolars |

|

M |

Molars |

Initial Periodontal Tooth Mobility (A)

This is defined as the first phase of movement of a tooth after loading at 1 N (ca. 100 p) in the orofacial direction. The tooth moves relatively easily within its alveolus. Some periodontal ligament fiber bundles are stretched, others relaxed, but significant deformation of the alveolar process does not occur.

Initial tooth mobility is relatively high: It is a function of the width of the periodontal ligament space and the histologic structure of the periodontium; depending on the tooth type, it can range from 0.05 –0.10 mm.

Secondary Periodontal Tooth Mobility (B)

This is measured after application of 5 N in the orofacial direction. At this magnitude of force, delivered via the stretched periodontal ligament fibers, the entire alveolar process is deformed and this resists additional deflection of the tooth.

Variations in periodontal tooth mobility in a healthy periodontium depend upon the mass and quality of the alveolar bone. The normal periodontal tooth mobility ranges from 0.06 to 0.15 mm, depending upon tooth type.

Occlusal Periodontal Trauma

Definition

Occlusal trauma is defined as “microscopic alterations of periodontal structures in the area of the periodontal ligament, which become manifest clinically in (reversible) elevation of tooth mobility” (Mühlemann et al. 1956, Mühlemann & Herzog 1961).

That an excess of pro-inflammatory mediators could increase occlusal trauma is suspected, but has not yet been proven.

Consequences

Occlusal trauma causes histologic alterations in the periodontium: Circulatory disturbances, thrombosis of PDL vasculature, edematisation and hyalinazation of collagen fibers, inflammatory cell infiltration, nuclear pyknosis of osteoblasts, cementoblasts and fibroblasts, as well as increases in vasculature diameter (Svanberg & Lindhe 1974). The periodontal ligament space adapts by becoming wider (“hourglass shape”), and this is manifested clinically by elevated mobility and radiographic evidence such as triangulation.

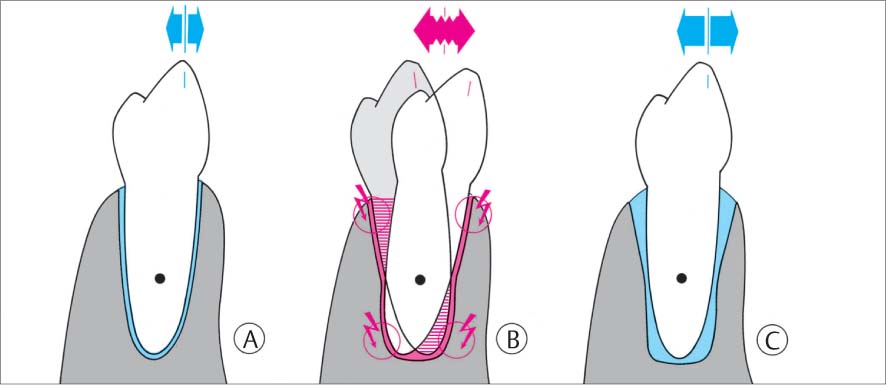

1131 Normal Periodontium—Primary Occlusal Trauma

A Healthy periodontium.

B If this tooth is unphysiologically loaded (parafunctions—jiggling), histologic changes will occur in the periodontium (red) and the PDL space becomes wider in areas of pressure (red arrows).

C The periodontal tissues can adapt to improper loading. The PDL space assumes an hourglass shape, which permits elevated tooth mobility.

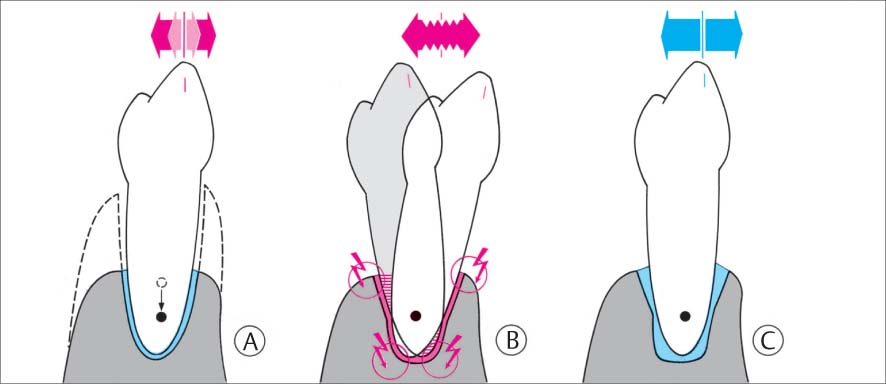

1132 Compromised Periodontium—Secondary Occlusal Trauma

A Elevated TM due to periodontitis.

B Even slight parafunctional loading will lead to additional elevation of tooth mobility (“secondary occlusal trauma”), leading to progressive tooth mobility.

C An adaptation with elevated tooth mobility may also occur.

Clinical experiments have proved that abnormal occlusal forces cause neither gingivitis nor periodontitis. However, the progression of an already existent periodontitis may be accelerated, especially during active stages of disease (Svanberg & Lindhe 1974; Polson et al. 1976a, b; Lindhe & Ericcson 1982; Pihlstrom 1986; Hanamura et al. 1987).

Adaptation to Unphysiologic Forces—Adaptive Phase

Even without treatment, the periodontium may adapt to long-term occlusal trauma. The PDL space remains wide, but retains its normal histologic appearance. Tooth mobility may remain elevated, but does not increase in severity (Nyman & Lindhe 1976).

Progressive Mobility with Unphysiologic Forces (Lack of Adaptation)—Progressive Phase

Heavy, continuous, abnormal occlusal forces may lead to progressively increasing tooth mobility, and function may be negatively influenced. The elimination of the causes of the trauma is then of primary importance.

Occlusal Bite Guard—The Michigan Splint

When parafunctional habits (e. g., bruxism) result in occlusal periodontal trauma (increasing tooth mobility) or to progression of periodontitis, the dentition should undergo selective occlusal grinding and wear facets should be eliminated.

However, selective grinding is often impossible due to spasm in the masticatory musculature. Reciprocal functional relationships exist among occlusion, the periodontal ligament, TMJ, masticatory musculature, and the central nervous system (CNS). The activity of the CNS may also be significantly influenced by psychic factors (Graber 1985).

Such central nervous system hyperactivity is relieved through elevated tone within the masticatory musculature (clenching or possibly also bruxism). In such situations, if occlusal disharmonies are also present, a “vicious circle” is created which can best be broken through use of an occlusal bite guard, e. g., the Michigan splint (Ramfjord & Ash 1983). The result is that the occlusion is taken out of the “circle” and the masticatory musculature relaxes. In most cases, selective occlusal grinding can then be accomplished after only a few weeks (removal of premature contacts and/or elimination of balancing side interferences).

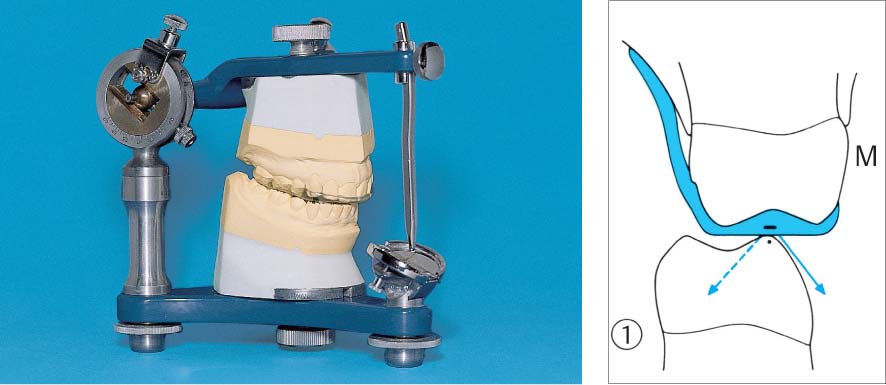

1133 Michigan Splint (Maxilla) in the Articulator

The removable bite guard is fabricated following registration of the occlusal relationships in an articulator; minimal bite elevation (splint thickness) is the goal.

Right: Transverse section (1) in the molar region where the cusps are relatively flat (M). In this region, the splint can be flat. During lateral excursions (working and balance side, blue arrows) contact is lost almost immediately due to canine guidance.

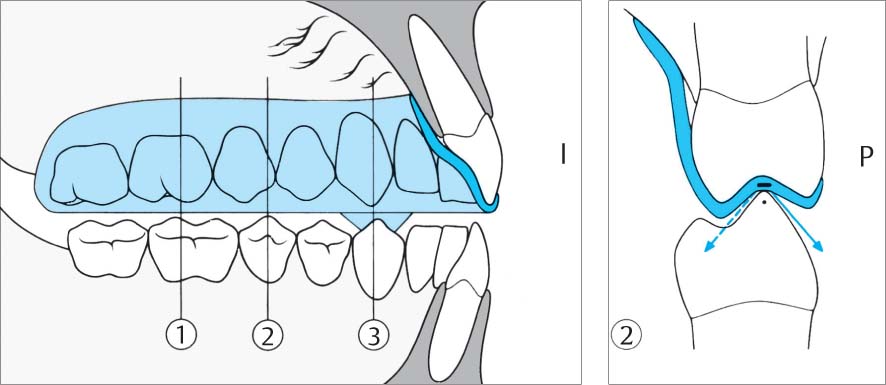

1134 Characteristics of the Michigan Splint

All buccal cusps of posterior teeth as well as canines and incisors (I) of the mandible occlude on the smooth acrylic surface of the splint. Transverse sections 1, 2, 3.

Right: In section 2, the steep cusps of the premolars (P), the profile of the splint is indented in order to prevent excessive bite elevation. Nevertheless, even here during lateral excursion (arrows) the working and balancing contacts must be immediately lost.

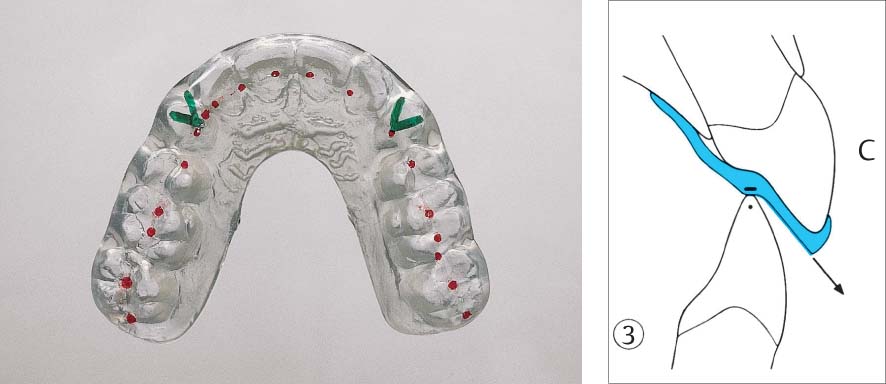

1135 Michigan Splint—Removable Bite Guard

The occlusal contacts between the splint and the buccal cusp tips of mandibular teeth are marked in red, and the guidance pathways for the guiding mandibular canines are shown in green.

Right: Section 3. In the canine region (C) a “cuspid rise” is incorporated: This steep incline provides the sole guidance of the mandible during lateral and protrusive movements.

Orthodontics

Periodontal and Esthetic Corrections

Anomalies of tooth position in a periodontally compromised dentition can be characterized as:

|

• Anomalies that have existed since tooth eruption • Anomalies that have resulted from periodontitis (or functional disturbances) |

A direct, causal relationship between existing dental malocclusion and periodontitis is difficult to document (Hug 1982, Zachrisson 1997, Ong et al. 1998, Thilander 1998). Dental crowding always makes plaque control more difficult. This leads to increased plaque retention, the consequence of which is increased gingival inflammation (Fig. 248).

But tooth migration must be differentiated from other anomalies; it only occurs over the course of time, and not seldom as a symptom/result of periodontitis. These sorts of intraoral manifestations frequently create esthetic problems for the patient, including:

|

• Protrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth • Tooth elongation • Torsion • Tooth tipping |

endo

Etiologies

The factors involved in the etiologic development of dental malocclusion following loss of periodontal support are not always obvious. Possible/probable causes include occlusal disharmonies (tooth tipping following tooth loss), oral para-functions such as tongue thrust or lip biting, occupation-related peculiarities such as holding nails or pins between the teeth, the playing of wind instruments etc. It has also been shown that not only the granulation tissue present in a deep periodontal pocket may exert a force that causes drifting, but that intact supracrestal fibers on the “healthy” side of a tooth may exert a pull resulting in tooth migration.

Treatment planning

Periodontal therapy must be completed before any orthodontic treatment is begun. The advantages and disadvantages of orthodontics must be considered. Is the treatment motivated by functional or esthetic concerns? Could the problem be solved by other means, e. g., by functional, morphologic or esthetic odontoplasty, or through prosthetic means?

Apparatus

If the decision is made to proceed with orthodontic therapy, depending upon the diagnosis, goal of treatment and difficulty of the proposed therapy, the myriad of therapeutic possibilities include simple wire ligatures, removable apparatus and fixed brackets on the facial/buccal or even – almost invisibly – on the oral/lingual aspect of the dentition. The choice will depend in many cases on the desires of the (adult) patient. Patients exhibiting difficulties in adequate plaque control may also lead to compromises (e. g., removable devices).

Risks

In a dentition with periodontitis, orthodontic treatment always represents an additional trauma for the remaining tooth-supporting structures. Tooth mobility increases in virtually every orthodontic case. This is fully comparable to the situation following occlusal trauma. Following orthodontic therapy, long-term retention is always required in a periodontally compromised dentition, at least in the form of semi-permanent splinting (p. 473) or a night guard.

Maxillary Anterior Segment Space Closure Following Periodontal Therapy

A 46-year-old female suffered from chronic and advanced periodontitis. In addition to bacterial infection (plaque), the etiology included severe psychic stress for family reasons, and the patient was overworked and weary.

The functional analysis revealed premature contacts between teeth 13, 14 and 45, 44, with a slight deviation from the left side anteriorally; this caused the maxillary anterior teeth to be mildly traumatized. Figures 1136 and 1138 depict the clinical view after initial periodontal therapy and subsequent surgical treatment.

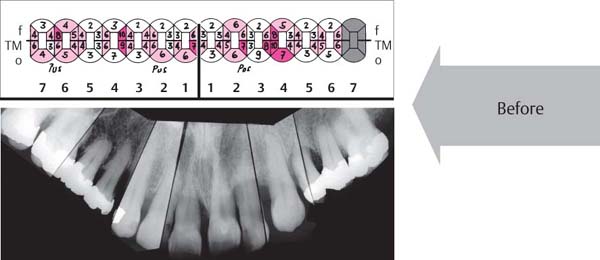

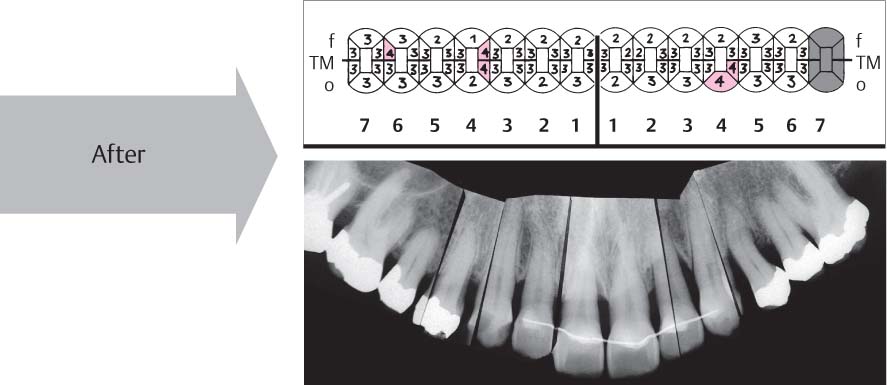

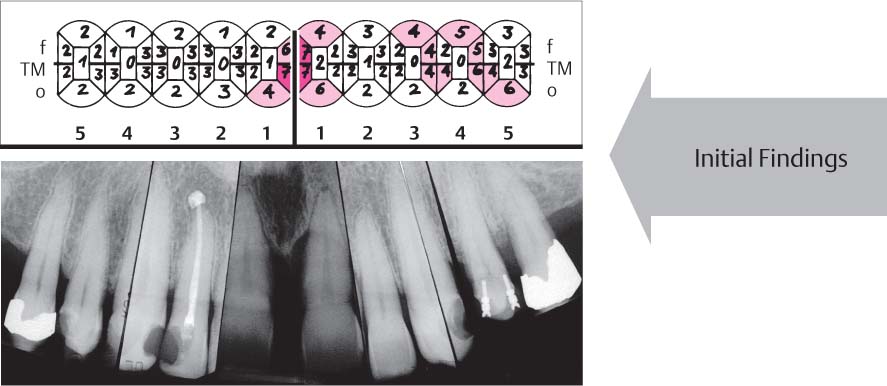

Figure 1137 shows the probing depths and radiographic appearance before any periodontal treatment. Initially the clinical values were

| PI: 70 % | BOP: 69 % |

During the periodontal therapy, protrusion and diastemata occurred and these bothered the patient. She desired esthetic improvement of her situation. Orthodontic treatment and conservative restorative therapy were indicated.

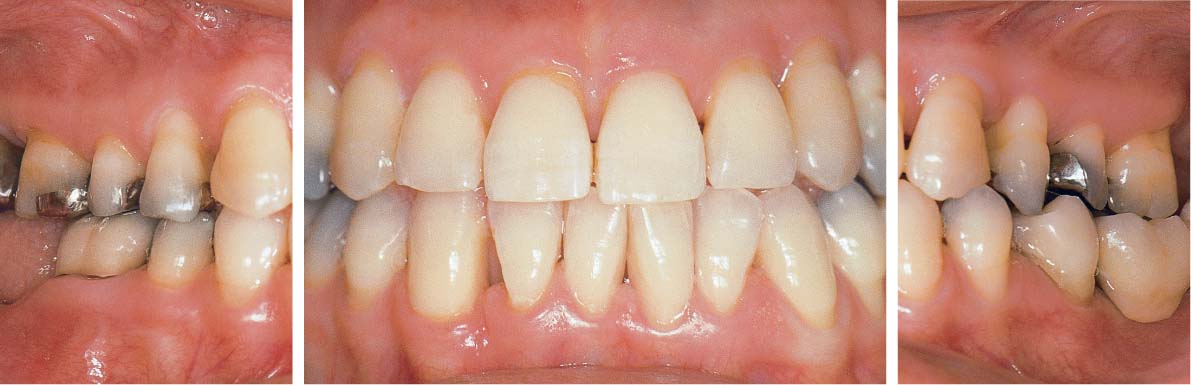

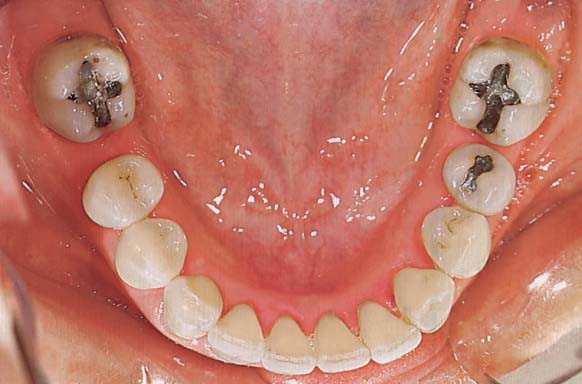

1136 Clinical View after Periodontitis Therapy (Above)

The periodontal treatment essentially eliminated the pockets (initial findings). However, morphology and texture of the gingiva remain less than optimal.

1137 Probing Depths and Radiographic View before Periodontal Therapy (Right)

Probing depths in the maxilla were particularly deep in the interdental and palatal areas. Note deep pockets on teeth 14, 11, 22, 23 and 24.

1138 Clinical Picture of the Maxilla after Periodontitis Therapy, Occlusal View

The gingiva exhibits essentially healthy relationships. The unharmonic arch configuration and the old restorations will be subsequently corrected and replaced.

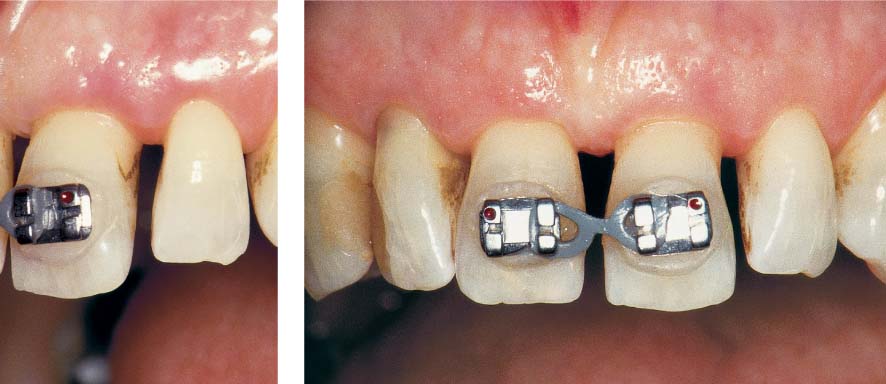

1139 Orthodontic Apparatus in the Maxilla

The treatment was performed using the segment-arch technique. At the time of this photograph, the treatment was nearing the final phase. The active orthodontic treatment required ca. 14 months.

1140 Clinical View Two Years after Completion of Treatment (Above)

Periodontal health and optimum esthetics.

1141 Probing Depths and Radiograph Appearance Two Years after Treatment (Left)

At most sites, the probing depths were reduced to physiologic levels. Several residual pockets of 4 mm remained. The radiograph shows stable relationships; in some areas, new formation of cortical bone.

1142 Occlusal Clinical View of the Maxilla Two Years after Completion of Treatment

The maxillary anterior teeth were maintained with a long-term retentive splint. The total conservative treatment was competed on all teeth. The gingivae exhibit healthy conditions.

Uprighting the Mandibular Second Molar

It is not necessary to prosthetically close every space in the dental arch. If the occlusion is stable and there is adequate periodontal/anatomic support, no drifting of the adjacent teeth should occur.

However, in a periodontally compromised dentition, tipping of a second molar into a first molar extraction site is common. The mesial tipping of the second molar leads to a plaque-retentive niche, which promotes the development of a deeper periodontal pocket (Ericsson 1986).

This was the case presented by a 48-year-old female with moderate periodontitis.

Tooth 38 was extracted during initial therapy, for endodontic reasons. Both mandibular second molars were uprighted during a 7-month period. The tooth movement was accomplished with an appliance incorporating a bite plane extending distally to the bicuspid area, a labial bow, and activatable uprighting springs for the molars.

Instead of the two fixed bridges, one might have considered dental implants to replace the missing first molars (Fig. 1145).

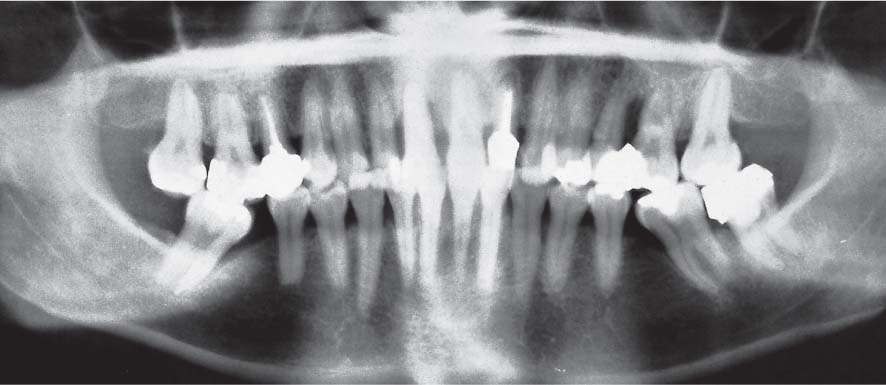

1143 Initial Panoramic Radiograph—Mesially Tipped Mandibular Molars

Following (justified?) extraction of the first molars years ago, the second molars had tipped severely into the spaces, forming treatment-resistant pockets (plaque-retentive niches). Whether or not dysfunctional occlusal loading of the tipped teeth is in any way responsible for the formation of mesial periodontal pockets has not been proven.

Tipped molar teeth often present balancing side interferences.

1144 Removable Appliance—Lateral Views

Mandibular appliance of clear acrylic incorporating an anterior bite plane, labial bow and uprighting springs.

Opening the bite was necessary to eliminate occlusal interferences on the molars during uprighting. In this case, it might have been possible to fabricate a somewhat less clumsy appliance!

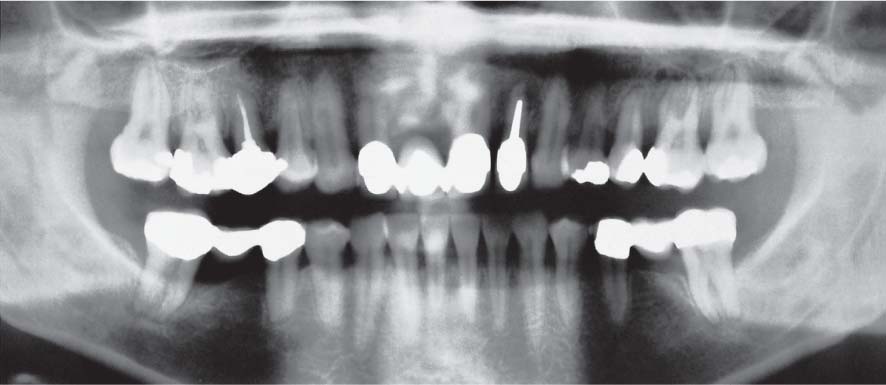

1145 Panoramic Radiograph after Treatment—Uprighted Mandibular Molars and 3-Unit Bridge Constructions Bilaterally

Tooth 38 was extracted and the two lower second molars were uprighted.

The two 3-unit bridges were seated immediately, making any additional orthodontic retention unnecessary. Definitive periodontitis treatment can now proceed. Effective plaque control by the patient is possible.

Courtesy P. Stöckli

The second molars (47 and 37) are severely tipped mesially.

The tipping has narrowed the extraction sites, making adequate oral hygiene difficult and promoting plaque retention. Pockets exist mesial to both second molars.

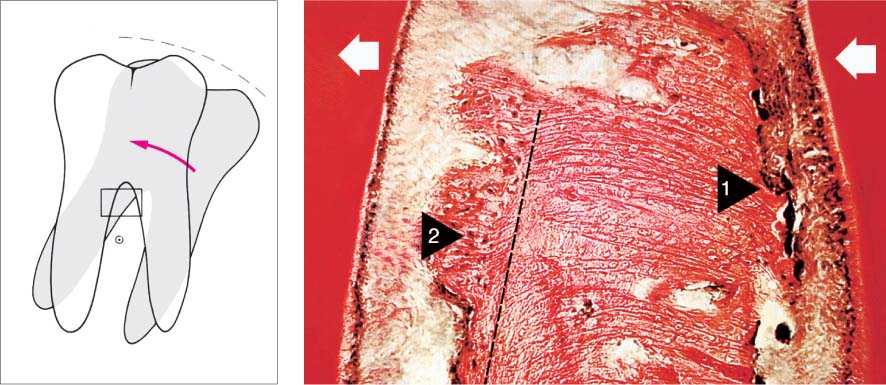

1147 Bone Deposition and Resorption During the Orthodontic Treatment

The histologic picture shows the region of the bifurcation (white arrows = direction of movement). In the zone of pressure (black arrow 1) one observes osteoclastic bone resorption, and in the tension zone (black arrow 2) bone apposition (van Gieson, 25x). Histology courtesy of N. Lang

Left: Molar uprighting occurs around a point of rotation between the roots.

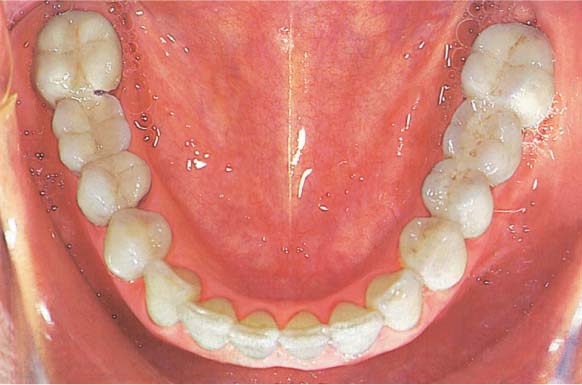

1148 Uprighting of the Mandibular Second Molars, Complete

The widened interdental spaces are clearly obvious (cf. initial view, Fig. 1146).

The buccal wall of tooth 47 has fractured (not due to treatment). For this reason, bridgework rather than dental implants was selected to close these spaces.

1149 Space Closure—Retention

Fixed bridgework maintains the uprighted molars and affords ideal replacement of the missing teeth.

The interdental spaces of the abutment teeth and bridge pontics were contoured to permit and facilitate the use of interdental brushes by the patient. Optimum oral hygiene is possible.

Courtesy P. Stöckli

Maxillary Anterior Esthetic Correction Following Periodontitis Treatment

A 56-year-old female complained of esthetic problems in the maxillary anterior segment (tooth migration and mild gingival recession, “long teeth”). A small diastema had been present even at age 20, but had become much wider during the previous ten years. This led the patient to seek possibilities for space closure and resultant esthetic improvement.

The patient was unaware of any other gingival problems. She smoked ca. 10 cigarettes per day, but stopped smoking during the treatment phase. Despite the relatively high plaque index, the gingiva did not exhibit significant inflammatory symptoms. In the maxillary anterior region, pocket probing depths up to 7 mm were detected. Tooth 21 exhibited significant attachment loss up to two-thirds of the root length.

| PI: 68 % | BOP: 58 % | TM: see Fig. 1151 |

Following periodontal therapy, a “simple” orthodontic treatment was planned for the maxillary anterior region.

1150 Initial View before Periodontal Therapy

Moderate, chronic periodontitis with profound osseous defects and migration of teeth 11 and 12. Mild gingival recession on all maxillary incisors and both canines. The magnitude of plaque accumulation and gingival bleeding was not necessarily expected upon initial clinical observation.

Right: Pronounced attachment loss on tooth 11 and especially on tooth 21.

1151 Pocket Probing Depths and Radiographic View

Pockets of ≥ 6 mm were observed in the maxillary incisor, canine, and premolar regions only on teeth 11, 21, 24 and 25.

Radiographic view: The films clearly reveal the especially pronounced attachment loss between the two central incisors.

Additional findings:

| •PI 68 % •BOP 58 % |

1152 After Initial Periodontal Therapy

Following supra- and subgingival debridement, there was shrinkage of the marginal gingiva, and in the depth of the pockets some “repair” (p. 206). The probing depths were reduced to 4 mm or less.

Right: Set-up of the treatment plan: Diastema—“distribution.” Movement of tooth 21 mesially (1.5 mm). Closure of the remaining interdental gap by “additive” measures using composite filling materials.

1153 Active Phase of Orthodontic Tooth Movement

The ca. 3 mm wide diastema between teeth 11 and 21 was reduced to ca. 1.5 mm. This also created a similar 1.5 mm wide diastema between teeth 21 and 22.

Left: Note the new diastema between teeth 21 and 22 occasioned by the orthodontic mesial movement of the central incisors.

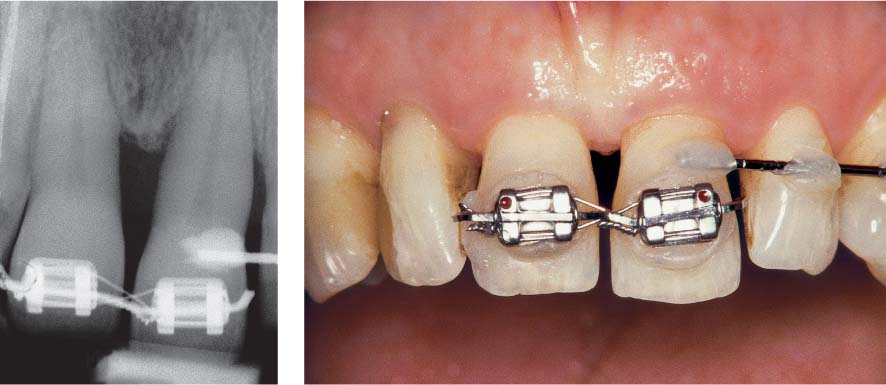

1154 Retention Phase—5 Months after active Orthodontic Treatment

Teeth 21, 22 and 23 are retained in their new positions using a simple arch wire affixed with composite resin. Tooth 11 is “supported” against tooth 12 using composite resin. Orthodontic retention of teeth 11 and 21.

Left: Radiographic taken during the retention phase.

In the apical region of the defect between teeth 11 and 21, new bone formation can be observed.

1155 Probing Depths and Radiographic Findings 7 Years (!) after Treatment

The patient is seen in recall every 6 months. The situation is stable. Only a few pockets exhibit probing depths of 4 mm.

Radiographic view: After consolidation of the attachment niveau post-therapy, stable relationships have been maintained over the years.

|

• PI < 10 % •BOP <10 % |

1156 Clinical View 7 Years later

Composite resin was used to splint 11 and 21 while simultaneously widening them. Tooth 21 was shortened. “Creeping attachment” alleviated the recession somewhat. The papillae between teeth 12 and 11 as well as between 21 and 22 regenerated.

Left: After removal of the brackets 7 years previously and before shortening of tooth 21 and composite resin treatment of the central incisors.

Courtesy J. Hermann

Treatment of the Malpositioned Canine

A 14-year-old female was referred because of extremely severe gingivitis and malpositioning of the maxillary right canine, which caused a plaque-retentive niche. This young girl’s oral hygiene was miserable. The patient proved extremely difficult to motivate. The erythematous, edematous, swollen gingiva bled at the slightest touch. Following initial periodontal therapy, a removable orthodontic appliance was selected in favor of a fixed appliance because of the unreliable patient compliance. Fixed orthodontic apparatus collects plaque biofilm readily and demand a higher level of oral hygiene from the patient.

A removable appliance can easily be cleaned when removed from the mouth, and also permits improved oral hygiene of the teeth. Financial considerations may also be a factor in the selection of fixed or removable orthodontic appliances.

| PI: 87 % | BOP: 80 % |

| Pseudopockets up to 7 mm | |

During orthodontic therapy, the patient’s oral hygiene improved following repeated OHI and motivation.

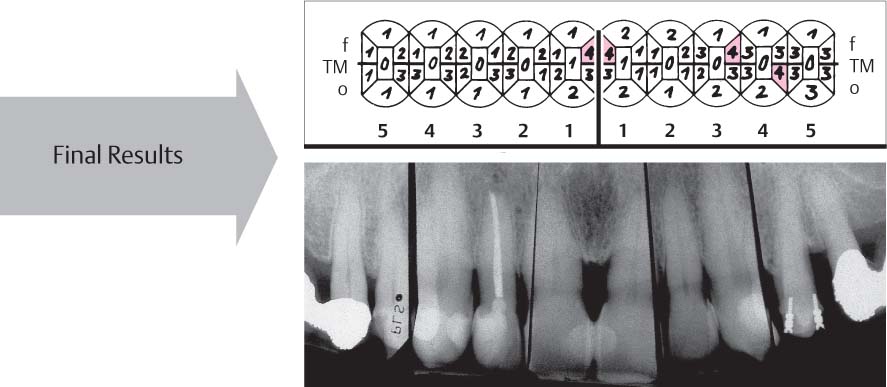

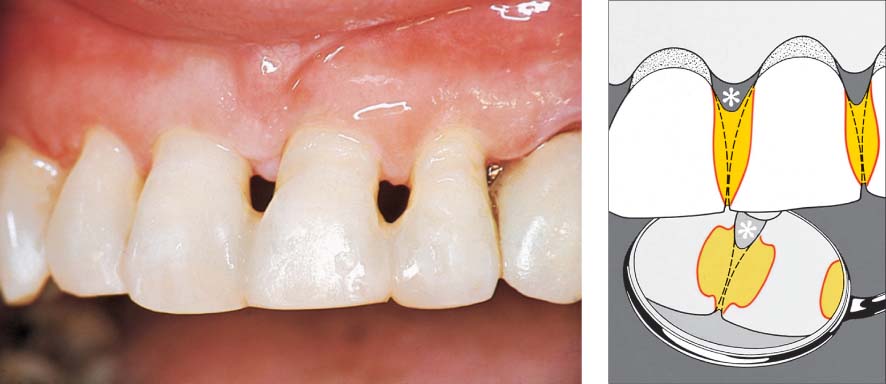

1157 Initial View—Malpositioned Canine, Severest Gingivitis

The plaque-disclosing solution revealed the enormous amount of plaque on all teeth. The severely malpositioned canine in combination with crowding created numerous plaque-retentive niches. Gingivitis was severe and pseudo-pockets were ubiquitous.

Right: Detail of 13, 12. When the gingiva was reflected, the massive subgingival plaque accumulations were visible.

1158 Removable Orthodontic Appliance

Following initial periodontal therapy, a palatal plate with a labial arch wire, guidance stops for tooth 11 and elastic facial springs for pulling the canine (13) into alignment.

The alignment of the canine could only be achieved following extraction of the premolar (14). The orthodontic treatment lasted about 1 year.

1159 Final Result 3 Years after Initiation of Therapy

The orthodontic result is acceptable. The patient (now 17 years old) became much more compliant and performed homecare effectively. Disclosing solution reveals only minor plaque accumulations. Bleeding on probing was virtually absent (BOP 5 %).

Right: Bringing the maxillary right canine into line made interdental hygiene much easier (use of dental floss is depicted).

Splinting—Stabilization

The significance, value and indication for immobilizing mobile teeth by means of permanent splinting remain controversial as a periodontal therapeutic technique. In order to clarify whether there exist any true indications for splinting, one must first consider the causes of tooth mobility:

|

• Quantitative loss of tooth-supporting structures due to periodontitis • Qualitative alterations of tooth-supporting structures resulting from occlusal trauma, above all parafunctions • Short-term trauma to the periodontium due to treatment for periodontitis • Tooth mobility caused by accidental trauma • Combinations of the above |

Mobile teeth whose degree of mobility is not increasing (elevated versus progressing tooth mobility), generally do not require splinting. Exceptions to this general rule include accidental trauma, and the elimination of severe parafunctions using temporary bite plates (p. 462, “Function—Functional therapy”). Tooth mobility caused by occlusal trauma should be treated primarily by selective occlusal adjustment (Vollmer & Rateitschak 1975), i. e., premature contacts and disturbances in lateral or protrusive excursions of the mandible should be diagnosed and eliminated.

Following selective occlusal grinding to remove parafunctions, bruxism such as clenching and improperly targeted loading, physiologic forces are distributed onto the entire dentition. Selective occlusal odontoplasty is targeted to remove the etiologic factors of parafunctions, the “trigger” factors, e. g., premature contacts, balancing side interferences etc.

In addition to purely occlusal disharmonies, psychic components may also be partially responsible for parafunctions and therefore also for tooth mobility. A combination of local treatment such as selective grinding combined with splinting may possibly be supported by psychopharmacologic medications, but only after consultation with the patient’s physician.

In recent years, splinting/stabilization of individual teeth or entire dental arches has become much more common because of the increased use of regenerative treatment methods. If the goal of treatment is not only new bone formation but also especially “new attachment,” i. e., the regeneration of all periodontal structures after treatment, this will most likely occur through some minimal temporary stabilization of the treated (mobile) teeth (to prevent dislodgment of the coagulum from the root surface).

Tooth Mobility and Healing

Following all types of pocket treatment, the pocket fills with blood. The fibrin net of the coagulum closely approximates the conditioned root surface. The organization of this coagulum, the formation of new periodontal structures (by periodontal ligament fibroblasts) requires several weeks. If a tooth is constantly mobile during this healing phase, the attachment (adhesins!) to the root surface will be significantly disturbed.

The demand for “stabilization” of the treated teeth is especially important after the use of regenerative techniques such as the implantation of bone and bone-replacement materials, and the GTR technique, as well as the use of growth factors and matrix proteins, and even combinations of these methods. Additional indications are illustrated below.

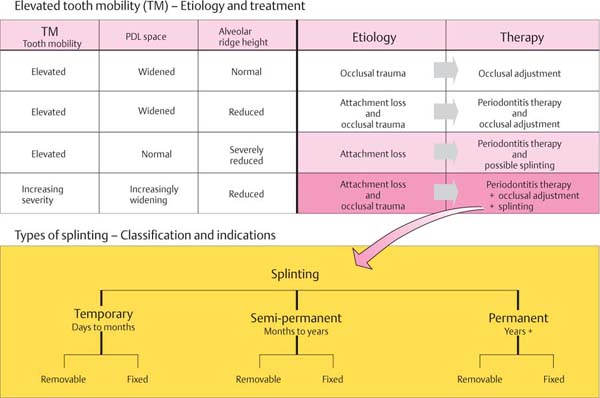

Elevated Tooth Mobility—Etiology, Treatment

The table below (modified from Flemmig 1993) attempts to define the causes and the necessary therapies for elevated tooth mobility; discussions in this regard are also dependent upon changes in the radiographic appearance of the periodontal ligament space (occlusal trauma) and clinical attachment loss.

Indications for Various Types of Splinting

• Temporary or semi-permanent: These protect against further trauma caused by occlusal and oral parafunctions (e. g., tongue pressing, “sucking”). It can be used as an emergency procedure with extremely mobile teeth. It also can serve to reduce trauma—mechanical, instrumental—during periodontitis therapy.

• Semi-permanent/permanent: This can enhance masticatory comfort when teeth are highly mobile; also to stabilize the teeth during periodontal healing phases, especially following regenerative therapies.

Awaiting the long-term prognosis.

Retention following orthodontic treatment.

• Permanent: Used for complex oral rehabilitation where abutments are highly mobile or where only few abutments must support the reconstruction, particularly when such abutment teeth have minimal periodontal support. Distribution of occlusal forces when parafunctions cannot be eliminated. In such cases, without splinting, there is a danger of progressively increasing tooth mobility and tooth migration (Nyman & Lindhe 1979).

Temporary Splinting

The simple wire ligature may serve as a fixed splint for a few days to several weeks. Wire ligatures are seldom used today, however, primarily because of the esthetic considerations. A more commonly used fixed splint is the acid-etch composite resin splint without tooth preparation, and sometimes with cavity preparation. Such a splint can be quickly applied with a rubber dam in place; however, it is a temporary measure because adhesion of the resin to the tooth structure is not strong enough without additional mechanical retention (cavity preparation, grooves etc.). Fracture of such splints is common if more than 3–4 teeth are included.

A removable, temporary splint can be made of acrylic resin pulled under vacuum, used only for a short period of retention for individual teeth.

Such splints were formerly used as a “bite guard” in the treatment of oral parafunctions. This approach proved not to be particularly effective and today the “Michigan splint” fabricated in a professional dental laboratory predominates.

1160 Wire Splint

Soft steel wire (0.4 mm diameter) is wrapped around the facial and oral surfaces of the teeth to be splinted, and the ligature/splint is tightened by twisting the ends. Stabilization of individual teeth is accomplished by application of interdental ligatures. Acid-etch resin “stops” may be applied to the labial surface to prevent the wire from sliding apically. The wire ligature/splint is used intraand post-operatively, in most cases in combination with a wound dressing.

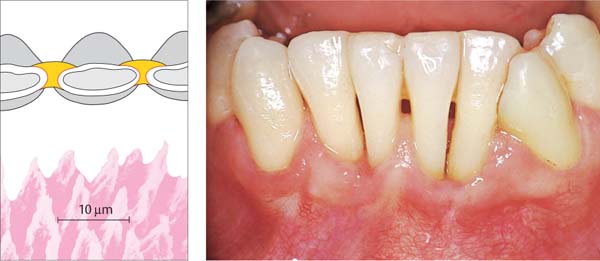

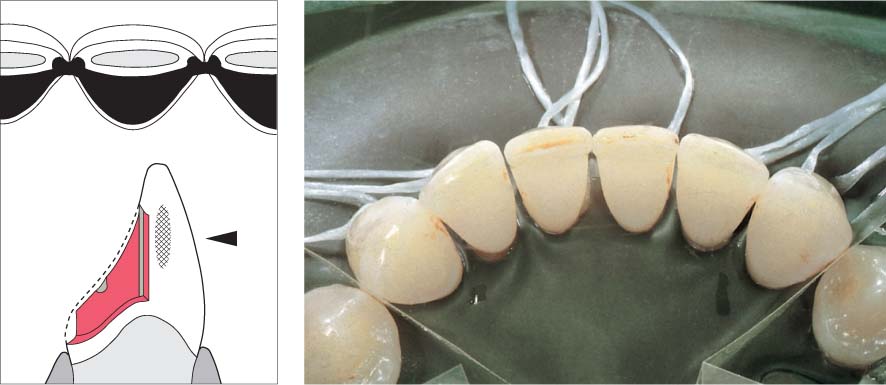

1161 Composite Resin Splint, no Tooth Preparation

Following thorough cleaning of the teeth, and under the rubber dam, the proximal surfaces are acid-etched and resin is applied. The apical region must be left open for oral hygiene.

Left: Above, incisal view of the resin splint in situ (red = etched enamel, yellow = resin).

Below: Etched enamel surface.

SEM courtesy F. Lutz

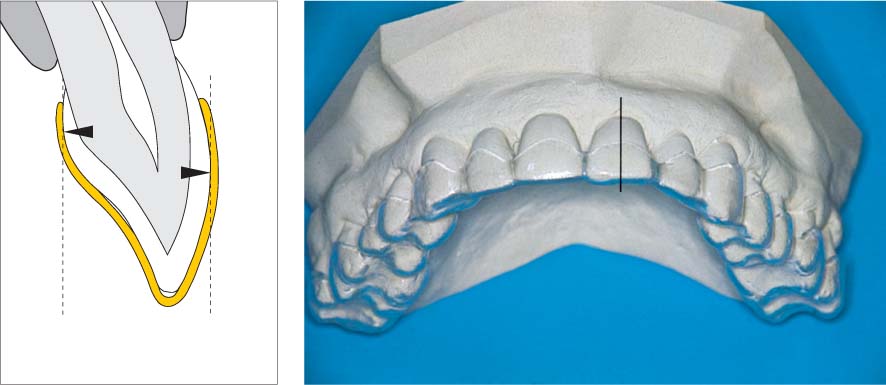

1162 Vacuum-Formed Removable Acrylic Splint

This splint can be used for short-term retention or stabilization of teeth.

Left: The border of the splint must extend beyond the height of contour of each tooth, orally and facially (black arrows) to provide secure retention.

Semi-Permanent Splinting—Anterior Area

The most frequently employed fixed, semi-permanent splint in the anterior region, which can remain in situ for months or even years, is splinting via composite resin (acid-etch technique) in combination with tooth preparation. It is often possible to simply remove all of the old anterior tooth restorations and subsequently incorporate the composite resin splint. The practical procedure is identical to the placement of composite restorations with the acid-etch technique.

The splint absolutely must be prepared with the rubber dam in place: Even tiny amounts of moisture after etching the enamel and during application of bonding and composite material will weaken the splint. Light-polymerized resin is recommended for this type of splint because of its long working time.

Removable semi-permanent splints may be fabricated as cast chrome-cobalt alloy frameworks incorporating typical partial denture clasps. This type of splint is indicated today only for wearing at night, often as a retentive appliance following orthodontic or surgical therapy.

1163 Composite Resin Splint with Tooth (Cavity) Preparation

This 38-year-old female was adamant that her almost hopelessly involved maxillary anterior teeth be retained.

Following initial therapy and up until the time that the long-term prognosis for the entire dentition could be established, the mobile teeth 11, 21 and 22 had to be stabilized. Proximal (Class III) restorations were removed.

Right: Radiographic view. Pronounced bone loss.

1164 Splint Application with the Rubber Dam in Place

After etching the minimally prepared enamel margins with phosphoric acid, the cavity preparations and the coronal portions of the interdental spaces are filled with light-cured composite resin, which is permitted to set and is then definitively polished.

1165 Three Years later

The interdental spaces were left open beneath the contact areas; this permitted good interdental hygiene using toothpicks and interdental brushes.

Right: Schematic depiction of the splint. Etched enamel (red), composite resin (yellow), combination of micro- (etching) and macro-retention (cavities). The asterisk (*) denotes the open interdental space (hygiene).

Permanent Splinting—Adhesive Technique

Soon after introduction of the acid-etch technique for anterior restorations, the so-called adhesive bridges and adhesive splints were propagated (Rochette 1973).

In recent years, this technique had been refined. In particular, various methods for enamel preparation have been developed, that ensure adequate retention of such reconstructions following only very conservative tooth preparation (Marinello et al. 1987, 1988). When splinting in the anterior segments, the proximal surfaces of the teeth are rendered parallel, and fine grooves are prepared. For occlusal support, shallow, peg-shaped depressions at the margin and above the lingual tubercle are created. The incisal edges are not included, for esthetic reasons.

In contrast to semi-permanent splints that simply bond adjacent teeth with acid-etch resin, bridges and splints prepared with the acid-etch technique can serve for definitive immobilization of mobile teeth (cf. p. 479).

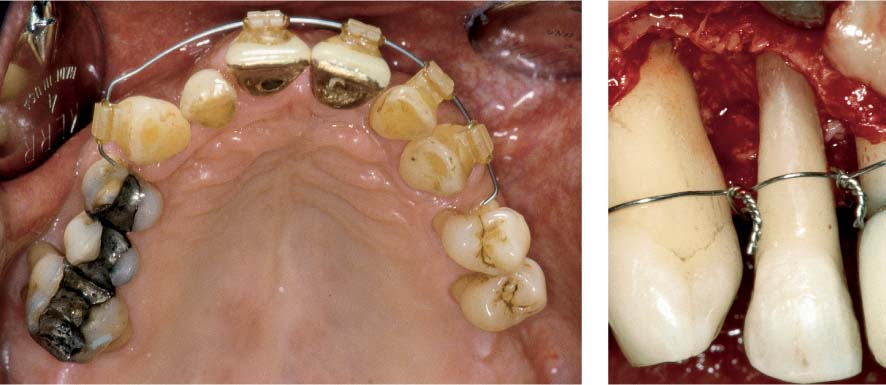

1166 Mandibular Anterior Area Following Initial Periodontal Therapy

The high degree of mobility of teeth 31 and 41 was particularly disturbing to the patient (insecurity, fear of tooth loss). To minimize the trauma of the impending periodontal therapy, and to improve patient comfort, a cast and cemented splint was planned.

Left: Radiographic findings: Particularly pronounced attachment loss between 31 and 32 and between 41 and 42.

1167 Before Seating the Splint

A rubber dam must be placed in the area of operation before acid-etching and subsequent seating of the splint. The elegant preparations (only in enamel!) are scarcely visible in this clinical picture.

Left: Preparation and splint form. The occlusal and lateral aspects depict the minimal tooth preparation. Enamel must be maintained, otherwise adhesion following acid-etching is not guaranteed, because only bonding to enamel is secure.

1168 After Seating the Splint with Composite Resin

Periodontitis therapy (subgingival scaling and possible surgical intervention) can be continued without compromise (time, poor temporaries etc.). The healing process can be observed over months or even years (long-term prognosis).

Left: Clinical picture three months after subgingival scaling.

Courtesy W. Iselin

Prosthetic Stabilization—Long-Term Temporary

In cases of advanced, aggressive periodontitis, the stability of the periodontal treatment result must be observed over an extended period of time before seating a definitive, fixed replacement. In order to avoid any trauma to highly mobile teeth during this consolidation phase, the use of a fixed long-term temporary may be warranted (p. 480).

Because of dental fear, this 48-year-old male had not visited the dentist for many years. Severe tooth mobility and migration, especially in the maxillary anterior segment, and spontaneous tooth exfoliation in the mandible finally led him to our clinic. The patient was a heavy smoker and was experiencing psychological problems (divorce). In the mandible, it was necessary initially to fabricate a complete denture (dental implants later?). In the maxilla, all of his teeth were retained, with the exception of tooth 27. Following initial periodontal therapy, open root cleaning/planing was performed (in some cases with temporary wire ligature retention) and thereafter minor orthodontic corrections:

| PI: 70 % | BOP: 56 % | TM: Grade 3 |

The clinical view and radiographs are depicted. When treatment was initiated, the patient was Aa positive.

1169 Initial Clinical View

Inflamed gingiva, pocket probing depths up to 10 mm, irregular tooth position within the dental arch, severe tooth migration particularly of tooth 21, old and corroded amalgam restorations.

Right: Radiographic view. In the maxilla, the bone loss approached two-thirds of the root length. In the mandible, the alveolar bone was actually apical to the root tips. Tooth 34 exfoliated spontaneously.

1170 Orthodontic Treatment

The planned fixed bridgework reconstruction required a harmonic dental arch and therefore demanded minor orthodontic procedures despite advanced attachment loss; in such cases these are easily performed.

Right: During open periodontal therapy wire ligature splints were applied to reduce trauma during the surgical procedure. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin and metronidazole as systemic supportive therapy.

1171 Long-Term Temporary Bridge

Following periodontal therapy, a metal-reinforced long-term temporary bridge was seated from 13 to 23 (unsure prognosis!). The patient had stopped smoking. He was so satisfied with the “temporary,” that he has not yet returned (after nine years!) to receive his “definitive” bridge.

Right: The visible metal crown margins were not an esthetic problem for the patient (who had a long upper lip and a mustache).

Perio-Prosthetics 1 Standard Techniques

In advanced periodontitis cases it is frequently not possible to maintain all of the teeth. During the treatment planning stage, teeth that are hopeless must be identified and extracted early on, because these teeth represent bacterial reservoirs. Such teeth can enhance the microbial re-colonization of other teeth (esthetics, temporaries?).

During initial therapy or at the very latest during surgical interventions it must be determined whether additional teeth must be sacrificed. In addition to the extent of periodontal attachment loss, other factors also play a role in the decision-making process:

|

• Must the lost tooth actually be replaced? • Might an exclusively premolar occlusion be satisfactory? (Käyser 1981; De Boever 1978, 1984) • Must every missing tooth absolutely be replaced, e. g., missing first molar and stable occlusion? • How important is the tooth as a strategic abutment for dental reconstruction? • Are there significant endodontic problems? • Are there inherited or genetic risk factors? • What is the overall prognosis for the entire dentition? |

Last but not least, the type of comprehensive dental reconstruction is less important than the ultimate maintenance or rebuilding of masticatory function, speech and (more and more today) esthetics; in short, the oral/dental satisfaction of each individual patient.

This chapter, Perio-prosthetics 1/Standard Techniques presents the following themes:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses