Chapter 11

General Anaesthesia

Aim

In this chapter we will review the use of general anaesthesia in respect of current legislation in the United Kingdom and explore its role in contemporary paediatric dental management.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter practitioners should be able to:

-

assess a child’s dental needs

-

understand the reasons for considering the use of general anaesthesia

-

refer correctly to the most appropriate specialist centre

-

understand the importance of follow-up preventive care to reduce the need for a future repeat general anaesthesia.

Introduction

Patients who are too apprehensive to undergo dental treatment solely with local analgesia may be managed with a skilful combination of local anaesthesia and sedation. Indeed, nitrous oxide inhalation sedation offers a strong alternative to general anaesthesia but it is not always potent enough to treat the recalcitrant child. Sometimes a general anaesthetic is necessary with a “pre-cooperative” child or because of the presence of acute infection, dental disease in several quadrants or a medical or learning disability (Fig 11-1).

Fig 11-1

“Pre-cooperative” children

We learned from previous chapters that the cooperation of a child is dependent on their level of emotional maturity, previous experience and on family influence, particularly maternal attitude towards dental treatment. Toddlers are generally “pre-cooperative” – they have very limited communication skills and few ways of expressing their anxieties and fears. Their ability to accept dental treatment is limited. When they feel unsure or threatened they try to escape and usually do this by crying. This crying is an aversive stimulus that prompts the listener to act – for example, the parent intervenes and stops whatever is making the child cry (Fig 11-2).

Fig 11-2 The precooperative child with toothache may need a general anaesthetic.

Why is general anaesthesia so commonly used in the United Kingdom?

An upturn in general anaesthesia activity was reported in north-west England in 1998, attributable to more children five years of age and younger having untreated caries due to the combined effect of an increase in caries and fewer decayed teeth being filled. Indeed, there is a clear correlation between the level of social deprivation and the numbers of decayed, missing and filled teeth in children. Children, especially those of pre-school age, who have the highest risk of dental caries are often not registered with a dentist, and consequently may not be receiving the intensive preventive and operative care that they need. Mothers of socially deprived children tend to delay taking their child to a dentist until their child is experiencing pain and are more likely to demand extractions. Therefore, dentists are still commonly presented with a child in pain who is attending their practice for the first time, and for whom extraction under a general anaesthetic appears to be the only option.

What is General Anaesthesia?

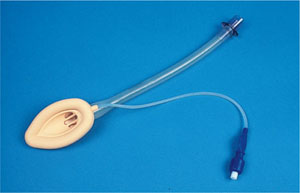

General anaesthesia is defined as “a controlled state of unconsciousness accompanied by a loss of protective reflexes, including the ability to maintain an airway independently and respond purposefully to physical stimulation or verbal command”. Thus general anaesthesia is any technique that produces a degree of depression of the central nervous system greater than that covered by the definition of conscious sedation. The respiratory function of a patient who is under a general anaesthetic is compromised since they are unconscious and unable to maintain the patency of their own airway. To overcome this an anaesthetist positions the patient in such a manner that the airway is maintained or uses Geudel airways, nasopharyngeal tubes or endotracheal intubation. In modern practice, laryngeal masks are increasingly popular [Fig 11-3]. General anaesthesia can be induced and maintained using inhalational or intravenous agents and there is a plethora of such techniques available, tailored to the suit each operative procedure and the needs of the individual patient.

Fig 11-3 A laryngeal mask.

Contemporary United Kingdom Legislation

The Royal Collage of Anaesthetists has advised that general anaesthesia should be strictly limited to those patients and clinical situations in which local anaesthesia with or without sedation is not an option. Moreover, the General Dental Council has announced amendments to its regulations precluding all but anaesthetists who conform to set parameters laid down by the General Medical Council from administering general anaesthesia for dental treatment. The referring dental practitioner for each case is obliged:

-

to give a clear written justification for the use of general anaesthesia

-

to take a full medical history

-

to explain to patients and parents the risks associated with general anaesthesia

-

to outline alternative methods of treatment

-

to provide a comprehensive referral letter

-

to keep a copy of their letter of referral.

In summary

-

Concern has grown about dental general anaesthesia for many years.

-

There has been increasing restrictions on its delivery.

-

This has led to a reduction of its use in general dental practice and reduced numbers overall.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses