Data from Nally JN, Meyer JM: Recherche Experimentale sur la Nature de la Liaison Ceramo-Metallique, Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnheilkd 80:250-277, 1970.

The conventional all-ceramic and acrylic resin full and partial coverage restorations, although esthetically pleasing, may fail under heavy occlusal stress because of low tensile and shear strengths.1 Newer porcelain materials are stronger but still cannot be used to create multiple-unit fixed prostheses.2 Full cast restorations offer sufficient strength but lack the esthetic appearance required in today’s society. Ceramometal dental restorations, however, offer both strength and acceptable appearance.3

The strength of the porcelain-to-metal bond is close to the tensile strength of the opaquing porcelain. Fracture usually occurs within the body of the porcelain. If this is not the case, an error in fabrication technique usually is to blame.1, 4, 5 Ceramic and metal alloys must have properties that allow for both physical and chemical compatibility. The fusion temperature of the ceramic (usually lower than 100° C) 1 is lower than the metal casting temperature, which prevents the cast metal substructure from melting during porcelain application.3 Ceramometal porcelains contain more soda and potash than typical all-ceramic blends; this increases thermal expansion to a level compatible with the metal alloy (the coefficient levels of thermal expansion for several porcelains are presented in table 9-3). The coefficient of thermal expansion of the ceramic is 13 to 14 × 10–6/°C. This should be approximately 0.5 to 1 × 10–6/°C less than the coefficient of thermal expansion of the casting alloy, which places the brittle ceramic into slight compression at the ceramometal interface when it cools. Ceramic is much stronger under compression than under tension.3 In addition, because it is brittle and tends to form minor stress-concentrating defects, the ceramic is much stronger when applied to a rigid metal framework. This framework, upon wetting with porcelain, reduces the internal ceramic defects and supports the brittle porcelain, thus adding strength to the restoration. 1 Conversely, the metal of a knife-edged finishing line or a bevel contains insufficient bulk to resist small deflections during seating. Porcelain should not be applied to these thin margins because if resistance to seating is encountered, flexing of the metal can cause the porcelain to flake off. 4

Table 9-3

Porcelain Coefficient of Thermal Expansion

Low Coefficient

Ceramco

Denpac

Vita

Excelco

Medium Coefficient

Pencraft

Duceram

Synspak

High Coefficient

Biobond

Williams

Crystar

Opaque porcelains, which mask the metal coping, contain metallic oxide opacifiers. New opaque porcelains can be used effectively in layers as thin as 100 μm. However, this opaque porcelain must be covered by at least 1 mm of body porcelain to mask its reflectiveness.

Vitrification in ceramic restorations refers to a liquid phase caused by reaction or melting which, on cooling, forms a glassy phase. If this formation is disturbed by the addition of too much modifying oxide, devitrification (crystallization) can occur.4 The ceramic porcelains are sensitive to devitrification because of their alkali content, which can cause clouding with additional porcelain firings. Repeated firing of high-expansion ceramometal porcelains at maturing temperature increases the likelihood of devitrification.4

Traditional dental ceramometal porcelains were formulated as a compromise between optimum properties and metal compatibility. The coefficient of thermal expansion of the porcelain had to be raised to approximate that of the ceramometal alloy. The ceramic metal had to be alloyed to cast at a higher temperature than conventional gold-copper alloys so that it could withstand the higher porcelain firing temperatures and reduced thermal expansion to meet that of the porcelain. Current ceramometal alloys have had their coefficient of thermal expansion adjusted to be compatible with conventional ceramometal porcelains (see table 9-3).

Ceramometal alloys

Ceramometal alloys must have a high modulus of elasticity to prevent deflection (are rigid) which could result in loss of portions of the porcelain veneer. Although the modulus of elasticity of commercial ceramometal alloys vary, they are clinically acceptable at a minimum thickness of one-half millimeter. Use of copings thinner than one-half millimeter risks perforation when fitting the restoration.

Ceramometal alloys should not melt during porcelain application or exhibit creep at high temperatures. (Creep is a strain that results in deformation or flow of the material over time when subjected to a constant stress). The most important aspect of the alloy chosen is that it must not distort, melt or exhibit creep with the high temperatures needed for its fusion with porcelain. That is, it must fit the tooth accurately after the porcelain is added.

When a ceramometal alloy is heated during porcelain firing, its modulus of elasticity must be high (rigid) enough to resist metal deformation. However, as the restoration cools, the alloy should be able to deform a small amount to relieve the stress produced by the thermal contraction of the porcelain. If the modulus of elasticity of the alloy is too high, it will be ungiving and be unable to relieve this stress. Thus, the stress remains in the porcelain and may lead to crazing.3

Creep is seen in metals at temperatures close to their melting point. It can be controlled by avoiding extremely long firing cycles. Creep is a time-dependent strain that occurs under stress and results in deformation or flow of the material.6 It is shown by a material that continues to deform even though the stress on it remains the same. High-temperature creep is flow that occurs at elevated temperatures. For gold alloys, high-temperature creep occurs at about 1800° F. It can be reduced by varying alloy composition so that a dispersion strengthening effect occurs at the high temperature.1,7,8

All intraoral restorative metals, including ceramometal alloys should be resistant to tarnish and corrosion in the mouth.3

Classification of ceramometal alloys

The two basic types of ceramometal alloys are the precious alloys and the base metal alloys.

Precious alloys.

Because original ceramometal restorations contained high proportions of noble metal, their clinical characteristics are well documented; they show good resistance to oxidation, tarnish, and corrosion.4 The noble metals are gold, platinum, palladium, iridium, rhodium, osmium, and ruthenium. Their physical properties are all similar, although the nongold noble alloys require a modified investment to withstand the higher casting temperatures. Ceramic alloys are very hard and strong compared with ADA Type I, Type II, and Type III gold; they are similar to Type IV gold. The coefficient of thermal expansion of ceramic alloys is less than that of any of the four types of gold. The noble metals and silver are often referred to as precious metals. Typical ceramometal alloy characteristics are presented in table 9-3.2

Base metal alloys.

Base metal alloys consist of nickel, chromium, molybdenum, cobalt, and beryllium. They can be used to obtain satisfactory fit, but laboratory procedures for base metals are much more technique sensitive than those for the noble alloys. High casting shrinkage of the base metal alloys necessitates special investments and casting methods. When nickel-based alloys are subjected to heat treatment during the porcelain firing cycles, the strength and hardness of the alloy diminishes. The base metal alloys’ oxide thickness is more difficult to control, which creates problems with additional porcelain firings.4

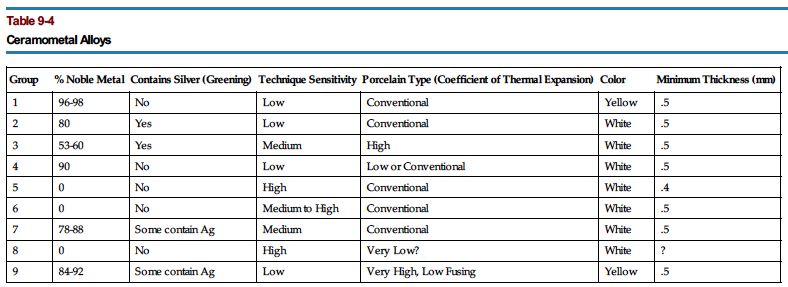

Dental ceramometal restorative alloys may be further classified by their major constituents and the chronology of their development (Tables 9-4 and 9-5). 2

Table 9-4

Ceramometal Alloys

| Group | % Noble Metal | Contains Silver (Greening) | Technique Sensitivity | Porcelain Type (Coefficient of Thermal Expansion) | Color | Minimum Thickness (mm) |

| 1 | 96-98 | No | Low | Conventional | Yellow | .5 |

| 2 | 80 | Yes | Low | Conventional | White | .5 |

| 3 | 53-60 | Yes | Medium | High | White | .5 |

| 4 | 90 | No | Low | Low or Conventional | White | .5 |

| 5 | 0 | No | High | Conventional | White | .4 |

| 6 | 0 | No | Medium to High | Conventional | White | .5 |

| 7 | 78-88 | Some contain Ag | Medium | Conventional | White | .5 |

| 8 | 0 | No | High | Very Low? | White | ? |

| 9 | 84-92 | Some contain Ag | Low | Very High, Low Fusing | Yellow | .5 |

Table 9-5

Properties of Ceramometal Alloys(F)

| Group | Type | Example | Au (%) | Pt (%) | Pd (%) | Ag (%) | Cr (%) | Ni (%) | Co (%) | Be (%) | Ti (%) | Proprietary Metals | Melting Range (EF) | Casting Temperature (EF) | Vickers Hardness | Yield Strength (psi) | Elongation (%) | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion | Density (gm/cm*) |

| 1 | Gold noble | Jelenko * | 88 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2100-2150 | 2300 | 182 | 65,300 | 5 | 14.7 | 19.2 | ||||||

| Degudent † | 78 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 2100-2300 | 2550 | 200 | 68,150(5) | 7(S) | 18 | |||||||||

| Rx CG * | 87 | 7 | 5 | 84,100(H) | 3(H) | ||||||||||||||

| Bio 86 ‡ | 86 | 11 | 0 | 2100-2150 | 2300 | 165 | 40,000 | 5 | 18.5 | ||||||||||

| 3 | 1870-2030 | 190(S) | 74800(S) | 9(S) | 14.5 | 18.9 | |||||||||||||

| 215(H) | 84500(H) | 7.5(H) | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | White noble | Cameo * | 53 | 27 | 16 | 4 | 2200-2300 | 2400 | 220 | 80,000 | 10 | 14.7 | 16.7 | ||||||

| Ceramco White | 51 | 31 | 15 | 3 | 2300-2345 | 2550 | 130(0) | 30,450(0) | 35(S) | 14.5 | |||||||||

| RxWCG ‡ | 52 | 30 | 14 | 220(H) | 61,630(H) | 10(H) | |||||||||||||

| 220(F) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 2200-2300 | 2400 | 220 | 80,000 | 10 | 13.8 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | Palladium silver | JeIstar. * | 60 | 28 | 12 | 2250-2380 | 2500 | 189 | 67,000 | 20 | 14.8 | 10.7 | |||||||

| Degustar | 52 | 38 | 10 | 2100-2250 | 2550 | 200(S) | 56,550(S) | 25(S) | 11.2 | ||||||||||

| Rx Palladent B* | 60 | 28 | 250(H) | 81,200(H) | 10(H) | ||||||||||||||

| 220(F) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 2200-2275 | 2500 | 165 | 0 | 10 | 10.5 | |||||||||||||

| 4 | Gold palladium | Olympia * | 52 | 39 | 9 | 2320.2380 | 2450 | 220 | 83,000 | 20 | 14.1 | 13.5 | |||||||

| Deva M † | 47 | 45 | 8 | 2230-2390 | 2550 | 185(S) | 53,650(S) | 31(S) | 14.4 | ||||||||||

| RxSF 45 | 45 | 45 | 275(H) | 94,250(H) | 10(H) | ||||||||||||||

| 260(F) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | 2200-2300 | 2550 | 250 | 80,000 | 10 | 14.6 | 13.5 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Nickel chromium | Rexillium ‡ | 75 | 14 | 2 | 9 | 2250-2350 | 2500 | 240 | 74,000 | 9-12 | 7.8 | |||||||

| 6 | Cobalt | Genesis | 27 | 53 | 20 | 2415-2550 | 2600 | 350 | 61,000 | 9 | 14.6 | 8.8 | |||||||

| Nouarex ‡ | 25 | 55 | 20 | 2425-2475 | 2675 | 260 | 90,000 | 7 | 8.8 | ||||||||||

| 7 | High palladium | Legacy * | 2 | 85 | 12 | 2020-2360 | 2450 | 270 | 95,500 | 20 | 14.2 | 11 | |||||||

| Deguplus 2 | 1 | 80 | 18 | 2110-2355 | 260(F) | 83.380(S) | 30(S) | 11.5 | |||||||||||

| Aspen ‡ | 6 | 75 | 7 |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses