All-Ceramic Systems—Clinical Aspects of the All-Ceramic Crown

Since the introduction of the porcelain jacket crown at the beginning of the 20th century, the all-ceramic crown has been the most aesthetic of all restorations. However, the demands made of it have always been high: The dentist must be able to prepare a circular shoulder and the dental technician must not only master a very complicated procedure but also possess the skill needed to reproduce natural-looking teeth. The technology used to make an all-ceramic crown has in fact been simplified, but great skill is still necessary to make beautiful, matching, and functional reconstructions.

Some clinical aspects that can contribute decisively to the success of a restoration are discussed in this section. One can produce aesthetically perfect anterior tooth restorations with all-ceramic crowns and ceramic veneers. Such restorations are successful only when every step in the treatment process, from planning to completed, correctly bonded, and adjusted restoration, is carried out equally well.

358 Translucency of all-ceramic crowns

All-ceramic crowns are as translucent as natural teeth, which is an advantage when creating aesthetic front teeth.

Indications and Contraindications

Although all currently available all-ceramic systems have excellent mechanical properties, the existing indications and contraindications of the all-ceramic crowns are comparable to those of the conventional alumina ceramic crown (McLean’s Pt crown). In fact, the flexural strength is a contentious issue when comparisons are being made. On the basis of the metal content, the metal-ceramic crown has a very high fracture strength that none of the all-ceramic crowns has reached.

In addition, the durability of the all-ceramic crown depends of many factors: treatment planning and patient education (hygiene phase), preparation of the tooth, making the impression, dental technical processing (many mistakes are possible), selection of cement and cementation technique, finishing, adjustments, and maintenance.

Indications for an all-ceramic crown:

—Front teeth that are destroyed, fractured, discolored, abraded, or are in a faulty position.

—Under favorable occlusal conditions, they can also be used to rebuild posterior teeth. However, the first choice regarding the use of treatment options for posterior teeth should remain the metal-ceramic crown until sufficient long-term results are available regarding the performance of all-ceramics in the molar regions.

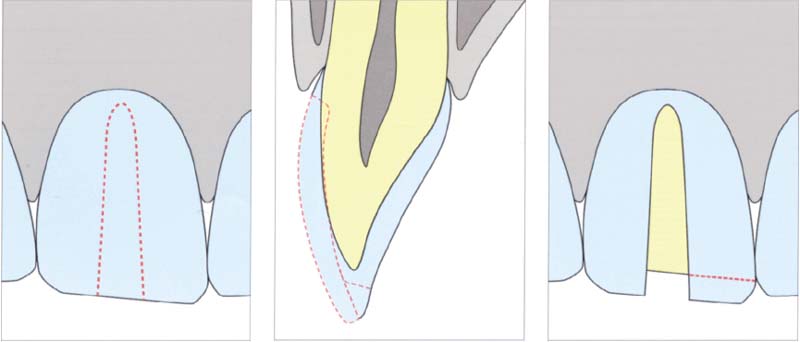

359 Preparing an all-ceramic crown

A depth cut is prepared to improve orientation. Layers in all-ceramic crowns must be at least 1.5–2 mm thick.

Left: Preparing a depth cut.

Middle: Cross section through the tooth with depth cut and incisal preparation.

Right: Incisal preparation

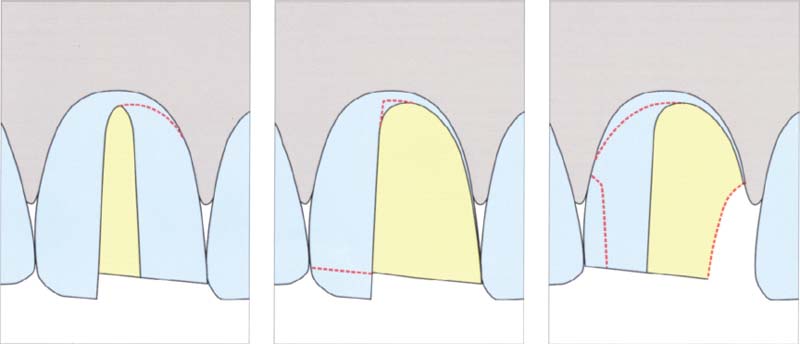

360 Step-wise preparation of half a tooth

After the depth cut is placed, the incisal edge is shortened accordingly, and one half of the crown is prepared. This approach enables control of the thickness of the layer of tooth substance removed.

Left: Preparation of half a tooth.

Middle: Incisal preparation of the second half a tooth.

Right: Residual preparation.

Contraindications are:

—too conical preparation

—insufficient lingual thickness of porcelain (<0.8 mm)

—deep bite

—short clinical crown that would only offer minimal retention after preparation

—parafunctions, for example, heavy bruxism

The principles of the tooth preparation for treatment with an all-ceramic crown are therefore:

—Virtually parallel mesial and distal axial walls, so that the proximal spaces are equally large.

—The length of the prepared tooth must be to at least two thirds of the incisal-cervical length of the restoration. A shorter preparation can increase the surface stress and lead to fractures.

—The incisal preparation must be rounded off.

—A uniform width (approx. 0.8–1.0 mm) of the cervical margin at an angle of close to 90 ° is important in order to resist pressure.

—All sharp angles and corners should be rounded off, in order to avoid concentrations of stress.

Preparatory Steps

1. Depth cuts: The depth cuts are cut on the facial surface and the incisal edge. The cuts are 1.0 mm deep facially and 2.0 mm deep incisally. One to three cuts are prepared facially parallel to the cervical first third of the facial surface. Then one prepares two cuts parallel to the incisal two thirds, and also two cuts 2 mm deep, positioned along the incisal edge.

2. Incisal and facial reduction: The incisal reduction is done parallel to the incisal edge of the crown. The facial surface is reduced in accordance with the appropriate cuts. An even reduction is imperative in order to get a smooth tooth structure. The prepared facial surface is finished and extended into the proximal areas.

3. Proximal reduction: The mesial and distal proximal walls are cut as parallel as possible. One should be careful that one does not prepare the proximal surfaces too profoundly and destroy the papillae by doing so. This could lead to unsightly interdental conditions.

4. Lingual-axial reduction: The reduction of the lingual-axial surface takes place to form a pointed angle of 5–6 ° to the cervical first third of the facial surface.

5. Preparation of the lingual concavity: The lingual surface is prepared so that between the lingual vault and the tooth surface there is a gap of 1.0 mm.

6. Finishing the marginal shoulder: The width of the shoulder on the facial and lingual surface should be 0.8–1.0 mm, and 0.6-0.8 mm on the mesial and distal surfaces. The shoulder must be shaped flat all around and the transitions between facial, mesial, lingual, and distal surfaces must be smooth. A right-angled rounded shoulder is preferred.

7. Rounding off all sharp corners and edges: All rounded-off surfaces should preferably be created with a low-torque FG diamond.

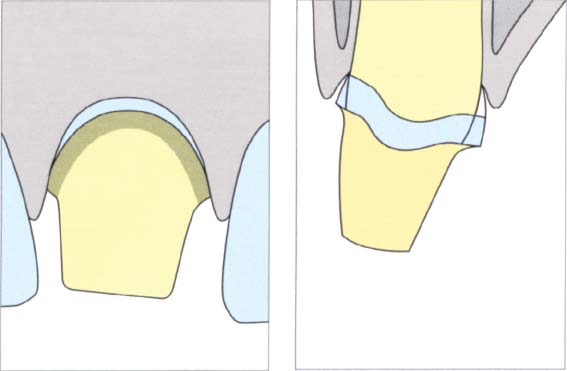

361 Preparation of the second half of the crown

Left: After one half of the crown has been prepared, the remaining tooth substance can be removed very easily. This procedure makes it possible to remove an even layer.

Right: The prepared crown in cross section.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses