9 THE METAL-CERAMIC CROWN PREPARATION

In many dental practices, the metal-ceramic crown is one of the most widely used fixed restorations. This has resulted in part from technologic improvements in the fabrication of this restoration by dental laboratories and in part from the growing amount of cosmetic demands that challenge dentists today.

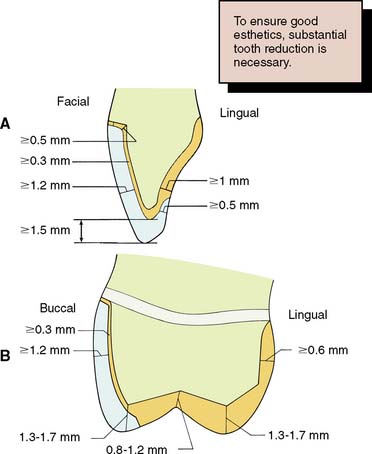

To be successful, a metal-ceramic crown preparation requires considerable tooth reduction wherever the metal substructure is to be veneered with dental porcelain. Only with sufficient thickness can the darker color of the metal substructure be masked and the veneer duplicate the appearance of a natural tooth. The porcelain veneer must have a certain minimum thickness for esthetics. Consequently, much tooth reduction is necessary, and the metal-ceramic preparation is one of the least conservative of tooth structures (Fig. 9-1).

The technical aspects of the fabrication of this restoration are discussed further in Chapter 24. For now, only a brief description is provided. The metal substructure is waxed and then cast in a special metal-ceramic alloy that has a higher fusing range and a lower thermal expansion than do conventional gold alloys. After preparatory finishing procedures, this substructure, or framework, is veneered with dental porcelain. The porcelain is fused onto the framework in much the same manner as household articles are enameled. Modern dental porcelains fuse at a temperature of about 960° C (1760° F). Because conventional gold alloys would melt at this temperature, the special alloys are necessary.

INDICATIONS

The metal-ceramic crown is indicated on teeth that require complete coverage and for which significant esthetic demands are placed on the dentist (e.g., the anterior teeth). It should be recognized, however, that, if esthetic considerations are paramount, an all-ceramic crown (see Chapters 11 and 25) has distinct cosmetic advantages over the metal-ceramic restoration; nevertheless, the metal-ceramic crown is more durable than the all-ceramic crown and generally has superior marginal fit. Furthermore, it can serve as a retainer for a fixed dental prosthesis because its metal substructure can accommodate cast or soldered connectors. Whereas the all-ceramic restoration cannot accommodate a rest for a removable prosthesis, the metal-ceramic crown may be successfully modified to incorporate occlusal and cingulum rests as well as milled proximal and reciprocal guide planes in its metal substructure (see Chapter 21).

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications for the metal-ceramic crown, as for all fixed restorations, include patients with active caries or untreated periodontal disease. In young patients with large pulp chambers, the metal-ceramic crown is also contraindicated because of the high risk of pulp exposure (see Fig. 7-4). If at all possible, a more conservative restorative option such as a composite resin or porcelain laminate veneer (see Chapter 25) or an all-ceramic crown with less reduction (see Chapter 11) is preferred.

DISADVANTAGES

The preparation for a metal-ceramic crown requires significant tooth reduction to provide sufficient space for the restorative materials. To achieve better esthetics, the facial margin of an anterior restoration is often placed subgingivally, which increases the potential for periodontal disease. However, a supragingival margin can be used if significant cosmetic concerns do not preclude it or if the restoration incorporates a porcelain labial margin (see Chapter 24).

PREPARATION

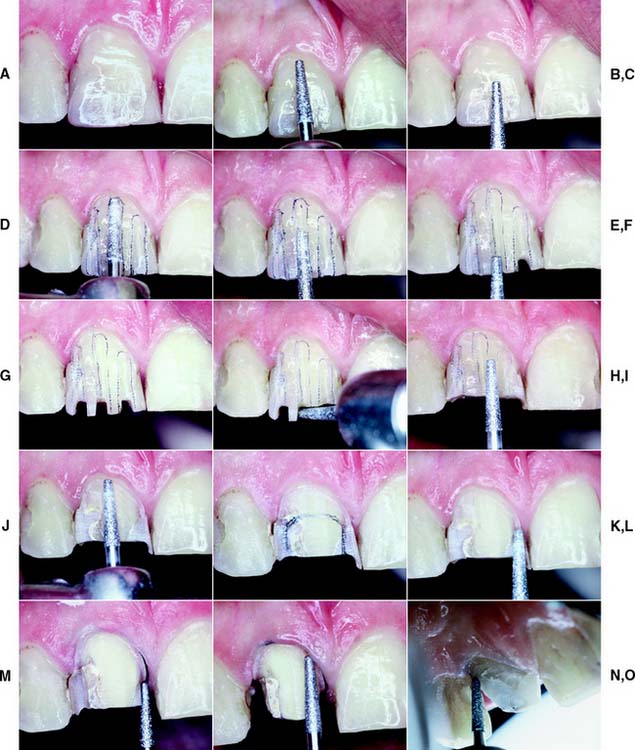

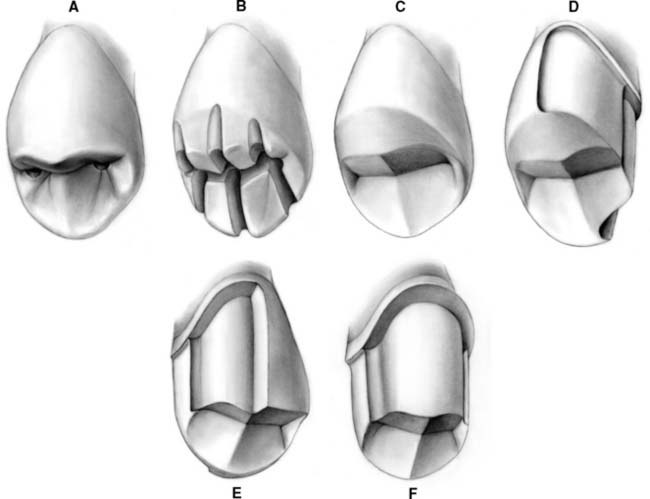

The recommended sequence of preparation is illustrated for a maxillary right central incisor (Fig. 9-2); however, the same step-by-step approach can be applied to other teeth (Fig. 9-3). As with all tooth preparations, a systematic and organized approach to tooth reduction saves time.

Armamentarium

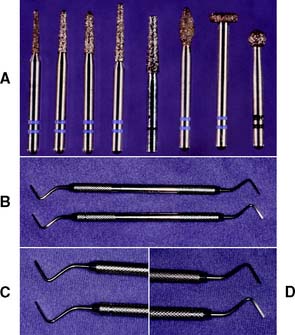

The instruments needed to prepare teeth for a metal-ceramic crown (Fig. 9-4) include:

The actual sequence of steps can be varied slightly, depending on operator preference.

Step-By-Step Procedure

Guiding grooves

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses