16 COMMUNICATING WITH THE DENTAL LABORATORY

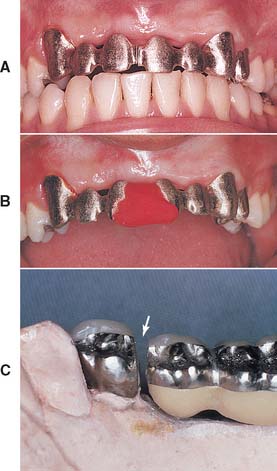

To make a high-quality fixed prosthesis, all members of the dental team must understand what they can reasonably expect from each other. A mutual knowledge of individual limitations is crucial. The dentist who does not understand and appreciate the challenges faced by the technician is at a serious disadvantage when prescribing and delegating laboratory procedures (Fig. 16-1). Crucial to the development of sound clinical judgment is a thorough understanding of technical procedures and their rationale, which are described in the chapters of this section.

DENTAL TECHNOLOGY TRAINING AND CERTIFICATION

The National Association of Dental Laboratories (NADL) is committed to upholding and advancing the commercial dental laboratory industry. This organization emphasizes the following information1:

In 46 states, there are no laws to set minimum qualifications for performance of dental technology or the operation of a dental laboratory. However, several states are moving forward with legislative proposals on “mandated technician certification.” The American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Dental Practice voted in 2005 at the NADL’s request to remove some policy language that was an obstacle to laboratory regulation/technician licensure through certification at the state level.2 Technicians and laboratories that become certified do so as evidence of their commitment to maintaining professional standards in dental technology. There are approximately 52,000 individual dental laboratory technicians in the United States. Because technicians are not required to be registered or licensed in most states, tracking has to come from various government and private sources.

The National Board for Certification, an independent board established by the NADL, offers voluntary certification in dental laboratory technology. Certification can be obtained in five specialty areas: crowns and bridges, ceramics, partial dentures, complete dentures, and orthodontic appliances. Certification is required in the states of Kentucky, Texas, and South Carolina. The standards and requirements for certification do not vary across state lines. A certified dental technician (CDT) tested in New England must demonstrate the same competencies as a CDT tested on the Pacific coast.

To qualify for certification, technicians must have a 2-year dental technology degree or at least 5 years’ experience in dental technology and must pass written and practical examinations. To maintain certification, they must document at least 12 hours of continuing education annually, including study of infection control (specific procedures designed to control the spread of disease agents). The requirements for a certified dental laboratory include having a Certified Dental Technician (CDT) present to supervise each department in the specialty, in which they and the laboratory are certified, to ensure that proper safety and production practices are followed. Certification must be renewed annually.*

The first CDTs were tested in 1958. Today the National Board for Certification tests more than 1200 technicians annually. In 1978, the current standards for laboratory certification were adopted; today there are more than 400 certified dental laboratories.2

MUTUAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Good communication is the key to the technical success of the dental team3–5 This requires a close working relationship between the dentist and laboratory technician. Anticipating satisfactory results is unrealistic if the dentist does not have a reasonable amount of experience with, and a thorough understanding of, dental laboratory procedures. Active participation in the technical procedures by the dentist is paramount, and clinicians who take the time to develop an in-depth understanding of laboratory work make better clinical decisions because of their understanding of applicable technical and material science limitations. Only then can a dentist select the best compromise between technical restrictions, on the one hand, and biologic factors and esthetic needs, on the other. Similarly, if the technician does not appreciate and respect the clinical demands or the treatment rationale of the dentist, the results will be less than satisfactory (Fig. 16-2). The dentist can earn this respect by being prepared to meet personal responsibilities, by listening carefully to technical advice rendered, and by actively participating in the technical decision-making process.

Surveys6–8 of fixed prosthodontic laboratories reveal that dentists delegate a significant proportion of their responsibilities. The technicians surveyed were often dissatisfied with the quality of work received; complaints included insufficient information being included in the work authorization, the submission of deficient impressions, and inadequate occlusal records. Such surveys highlight significant problems in dentist-technician communication. In other studies and opinions concerning dentist-technician interaction, whether written by dentists or technicians, the authors emphasized that better patient care is achievable only by better patient care communication.9

The ADA has issued guidelines to improve the relationship between dentist and technicians.10 They are reprinted here:

The Dentist

The Laboratory Technician

RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE DENTIST

Infection Control

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services11 and the ADA12 have issued guidelines about the disinfection and handling of impressions and other material transferred from the dental office to the dental laboratory. Applicable guidelines are detailed in Chapter 14. Strict adherence to infection control guidelines cannot be overemphasized, because the potential for infection of dental laboratory personnel exists. In a 1990 sample,13 of all materials sent from dental offices to dental laboratories, 67% were contaminated. Results from a more recent questionnaire submitted to dental laboratories suggest that technicians believed in less than 60% of the cases that materials had been appropriately disinfected before being submitted to the laboratory.8

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses