CHAPTER 9

Factors Related to Relapse

“Round up the usual suspects.”

—Claude Rains as Captain Renault in the film Casablanca

Most orthodontic research suggests that rotated or crowded mandibular anterior teeth are the most likely teeth to relapse. Although such relapse occurs in our practice, it has been only a minor problem. Transverse relapse is also apparent only rarely. In our practice, the most prevalent form of relapse is bite reopening in open bite cases. The orthodontically closed bites of high-angle patients who are still tongue thrusting or mouth breathing during retention seem to reopen. It is very important, therefore, to eliminate these habits during treatment, if possible. Relapse problems are caused by noncooperation and/or muscular habits. Not wearing retainers obviously can allow relapse to occur. Muscular habits such as thumb sucking, tongue thrusting, and mouth breathing can place abnormal forces on the dentition to cause significant relapse.

Approximately 80% of our cases experience no significant relapse, 15% relapse only very slightly, and about 5% show meaningful relapse. Again, these are usually due to muscular problems. We are always willing to re-treat any patient who returns to our office complaining of relapse. It seems prudent to re-treat the patient for two reasons. First, we would like every patient who leaves our office to be completely satisfied with the treatment performed. Second, we want all of our patients to have the best possible result. Re-treating patients is a perfect example of altruistic egoism. If the patients look good and are happy with their orthodontic treatment, they will continue to speak highly of the practice, which will ultimately result in additional referrals.

The big question concerning re-treatment is financial responsibility. Does the clinician absorb all cost? Does the patient pay for it? Is there a compromise? This situation must be discussed with the patient. Together we make a decision. The patient is asked, “Do you think your teeth have shifted back because you didn’t wear your retainer and didn’t follow our instructions, or was it because we never got the teeth where they belong in the first place?” Almost invariably, the patient will admit to haphazard retainer wear. In this situation, the patient is re-treated at a nominal fee.

Possible Sources of Relapse

Just as Claude Rains in the classic movie Casablanca ordered his soldiers to “round up the usual suspects,” so too let us evaluate the “usual suspects” of orthodontic relapse.

Mandibular incisor position

The Tweed concept is that mandibular incisors should be upright over basal bone. I believe wholeheartedly in this philosophy. Many orthodontists today do not pay sufficient attention to torque control of the mandibular incisors. When the mandibular incisors are indiscriminately tipped or advanced, the clinician is creating a danger for potential relapse, especially for a tight-lipped person. The health of the dentition and gingival tissue are also affected adversely when the mandibular incisors are not positioned over basal bone.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some orthodontists retract the teeth lingually until they are too far upright. This retraction creates an esthetic problem with the facial profile. The resulting dished-in appearance is unacceptable in my opinion. The–5-degree mandibular anterior torque built into the long-term stability brackets allows a “happy medium” to be established quite easily in most cases.

From the stability standpoint, if mandibular incisors are placed too far lingually, the teeth do not tend to advance spontaneously. The balance between the lip pressure and tongue pressure is not violated to a large enough degree to cause a great amount of relapse. In this case, however, the interincisal angle may be too obtuse, causing a tendency for relapse of the overbite as well as a concave soft tissue profile.

If the teeth were placed in the appropriate positions during active treatment, interproximal reduction was properly performed, and third molars were resolved, then the chance of the result remaining stable after retainer removal is excellent.

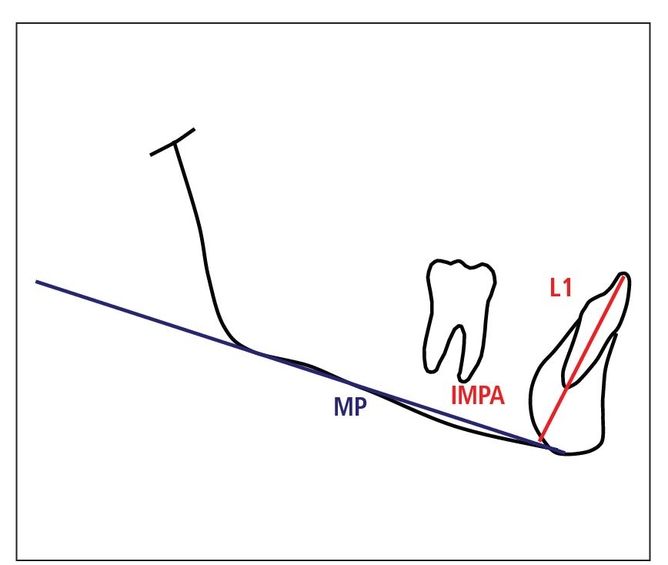

In the Glenn study, the incisor mandibular plane angle (IMPA) averaged 94.5 degrees pretreatment.1 IMPA averaged 94.8 degrees after treatment. Postretention 8 years later showed IMPA at 95.1 degrees.

Fig 9-1 IMPA can be advanced 3 degrees.

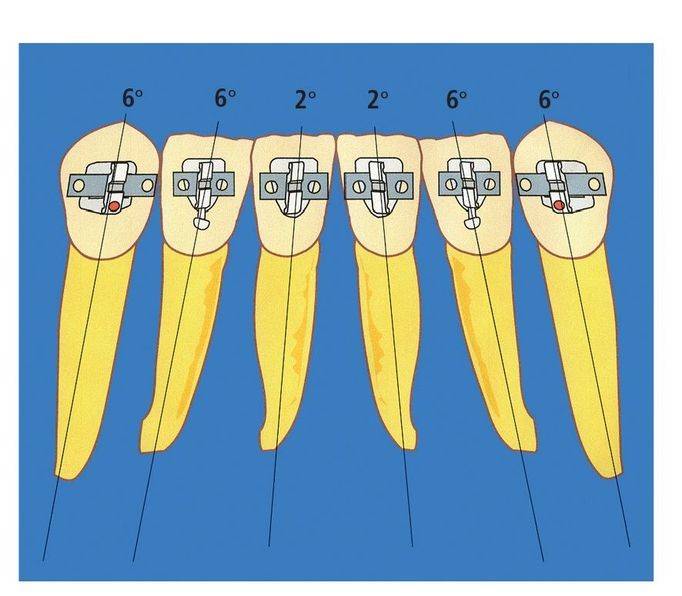

Fig 9-2 Root positions of mandibular incisors.

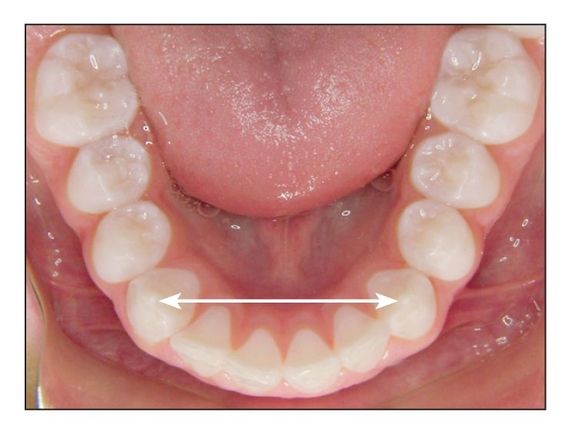

Fig 9-3 Mandibular intercanine width can be expanded by 1 mm.

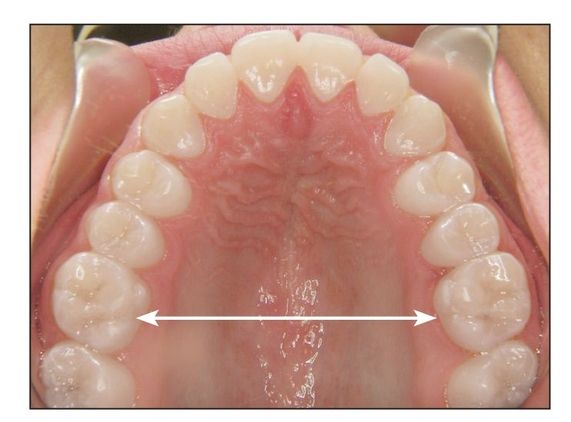

Fig 9-4 Final maxillary intermolar width should be between 34 and 38 mm.

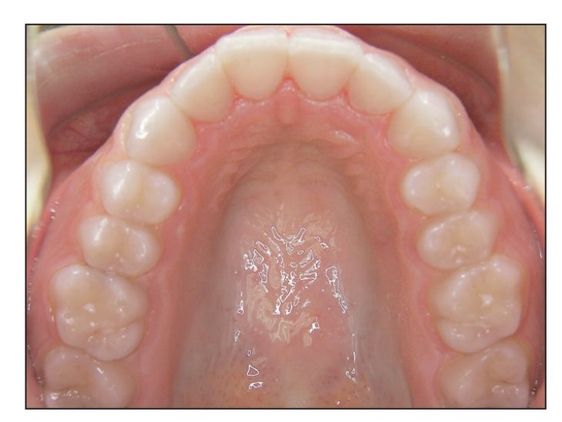

Fig 9-5 Ovoid maxillary arch form.

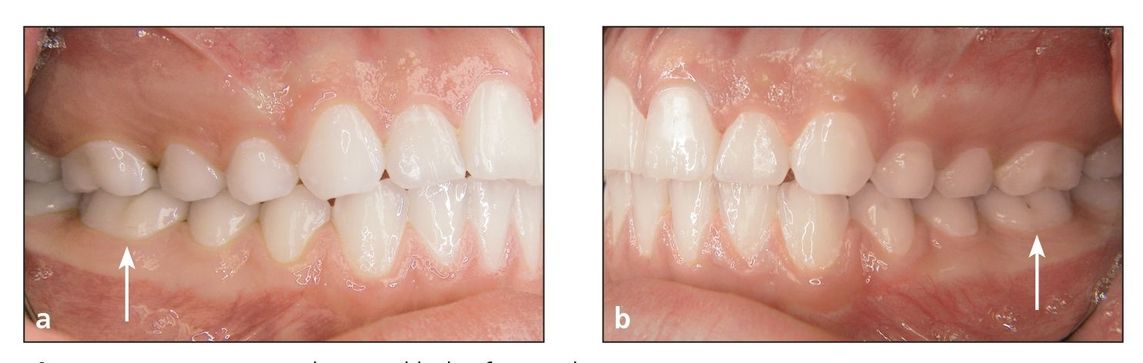

Fig 9-6 (a and b) Upright mandibular first molars (arrows).

Skeletal Stability

In my opinion, as discussed earlier in this book, there are s undisputed facts related to mandibular stability:

- IMPA: 3-degree rule (Fig 9-1)

- Mandibular incisor roots spread (Fig 9-2)

- Mandibular intercanine width: 1-mm rule (Fig 9-3)

- Maxillary intermolar width: between 34 and 38 mm (Fig 9-4)

- Ovoid maxillary arch form (Fig 9-5)

- Upright mandibular first molars (Fig 9-6)

But what about long-term stability with the hard tissues?

Muscular Suspects

Earlier in this chapter we identified “the usual suspects” that we as orthodontists can control or correct to help prevent relapse. But what about the following muscular interferences?

- Tongue thrust when swallowing

- Mouth breathing

- Thumb sucking

These abnormal muscular pressures placed on the teeth counterbalance the normal muscular forces. The usual result from these abnormal muscular functions is an open bite.

Open bite

An interesting question is whether open bites are inherited or acquired. How often do you see a vertical growth pattern in patients whose permanent first molars have not erupted? Unless the patient is a thumb sucker, this phenomenon does not seem to present itself often. This is strictly my observation.

However, as the permanent first molars erupt, if the patient does not swallow properly, the first molars can “super” erupt, creating a vertical skeletal pattern and possibly an anterior open bite.

Is environment a factor? Pollution from the air we breathe? Artificial flavoring and coloring in the food we eat? These could cause allergies and nasal congestion, creating the need to breathe through the mouth. This can create reduced occlusal forces, allowing the molars to continue erupting and creating a high-angle open bite malocclusion.

Clinically, I believe the greatest factor in the development of high-angle, open bite occlusions is the lack of proper muscular function. Inadequate occlusal forces can allow teeth to drift vertically. Could this have a negative effect on growth, causing vertical growth and open bites? What would happen if we taught our patients to get their muscles of mastication in shape?

Doug Thompson placed dental students on a training regimen of clenching isometrically on a 1-mm thickness soft splint.3 Prescriptions consisted of five 1-minute exercise periods per day in which the students were supposed to squeeze their teeth together, hold for 15 seconds, release, and repeat four times. Maximum bite force changes were measured at 3-week intervals. Over a period of 6 weeks, maximum bite forces increased 18% more in the experimental group, and resistance to fatigue was significantly increased clinically. Does it not make sense then that strengthening the muscles of mastication in open bite patients could have a positive effect on the open bite problem?

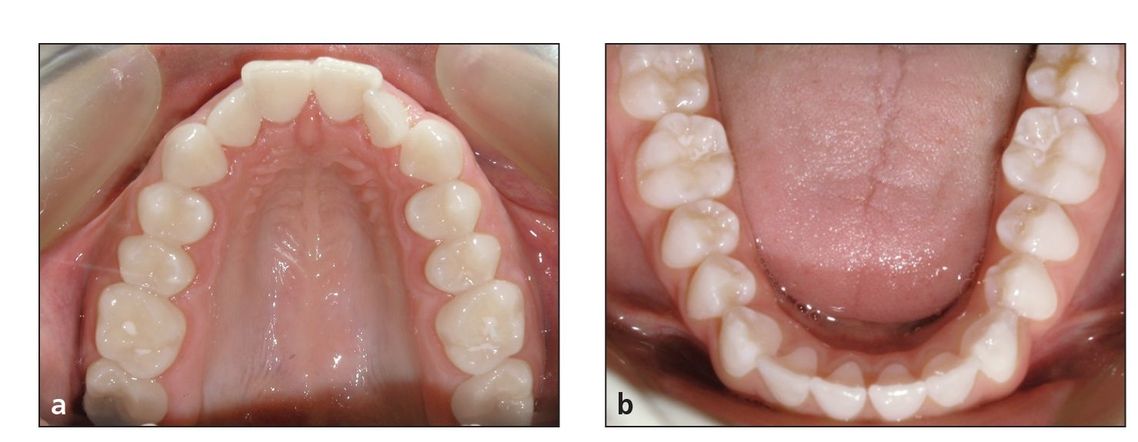

Fig 9-7 Pretreatment V-shaped maxillary arch form (a) and broad mandibular arch form (b).

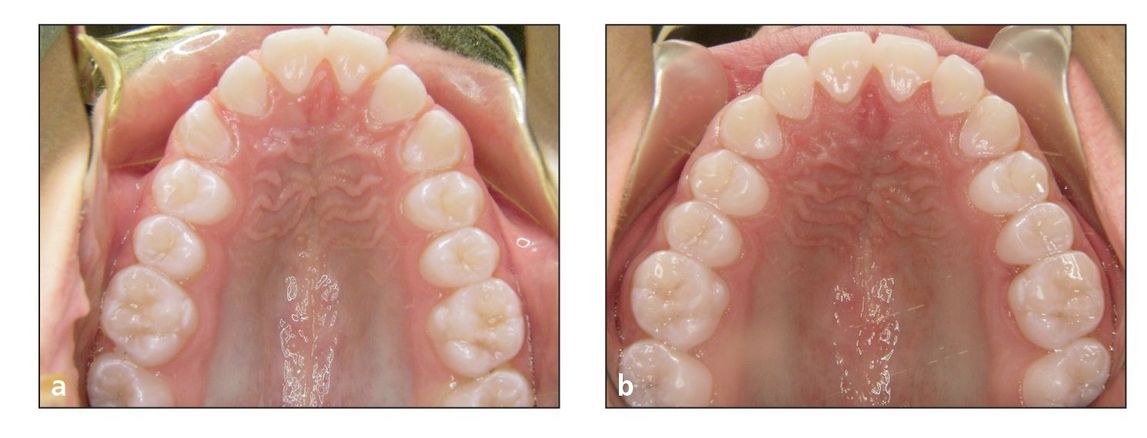

Fig 9-8 (a) Pretreatment V-shaped maxillary arch form. (b) Posttreatment ovoid maxillary arch form.

Myofunctional Therapy for Open Bite

Abnormal muscular habits can influence the shape of the arch forms, especially the maxillary arch in a Class II skeletal pattern (Fig 9-7). Thumb sucking, tongue thrusting, and poor resting position of the tongue all can relate to the shape of the maxillary and mandibular arch forms.

When the maxillary intermolar width is less than 33 to 34 mm, the tongue position will naturally tend to rest in a wider area in between the mandibular teeth rather than in its normal position in the palate. This can widen the mandibular arch over time while the buccinator muscles will continue to constrict the posterior maxillary intermolar width. This will create the typical V-shaped maxillary arch form and occasionally create posterior reverse articulations.

Almost every patient who has this V-shaped maxillary arch form will not swallow normally but will instead have an anterior tongue thrust. This, of course, will increase the flared position of the maxillary anterior teeth, making the situation worse by increasing anterior overjet.

To permanently correct this problem, two changes must be achieved. Routinely in our office, we first attack the narrow maxillary intermolar width. Usually this is accomplished with a rapid palatal expander. In minor cases, an expanded archwire can be used, along with the inner bow of the facebow, if needed. After expansion, it should be held open with brackets and archwires.

The second change is the maxillary arch form, which will change from the V-shaped arch to our typical ovoid arch form (Fig 9-8). During this period of treatment, the skeletal Class II problem and intermolar width often can be successfully addressed with the facebow.

In the meantime, the tongue may become “disoriented” with the new internal environment, with its changed arch form and more occlusally balanced anterior/posterior skeletal relationships. After the new and normal maxillary arch is achieved, the tongue will not naturally adapt to its new environment; it will need some coaching. If long-term stability is a goal, the patient must learn how to swallow properly, using the “sounds of swallowing” technique described later in this chapter. If this does not occur, the tongue will revert back to its previous thrusting habit once the appliances are removed, and relapse will certainly be the long-term result.

Therefore, while the arch is being widened and reshaped, the muscles of mastication should be “educated” on how to swallow properly. As orthodontic treatment progresses, in addition to the new arch forms and elastics, the open bite is mechanically closed, making it easier for the tongue to adjust and adapt to its new environment.

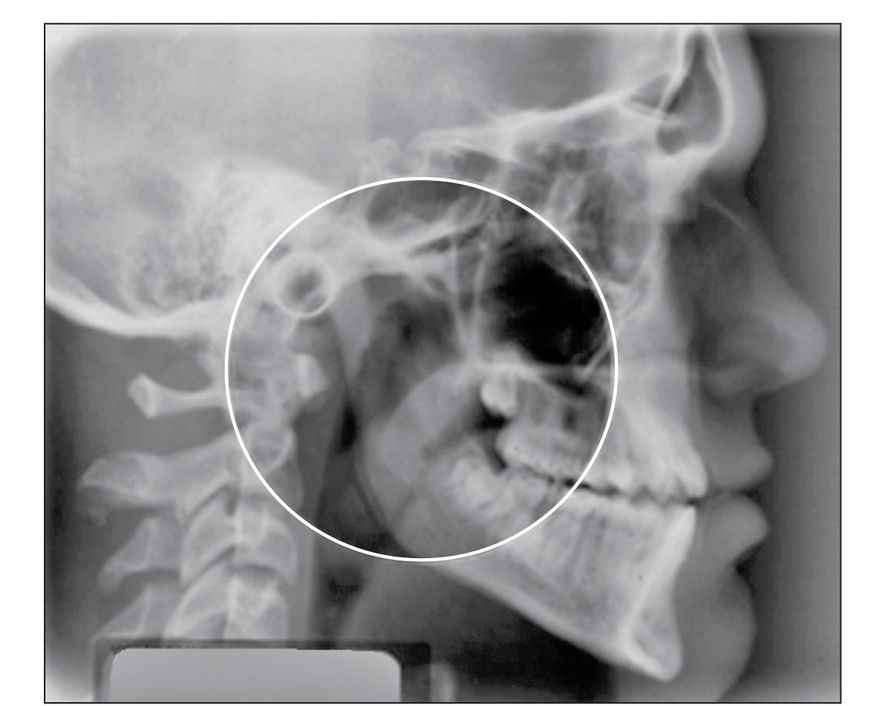

Fig 9-9 Diagnostic lateral cephalogram. The circle surrounds the adenoids and tonsils, which can affect mouth breathing.

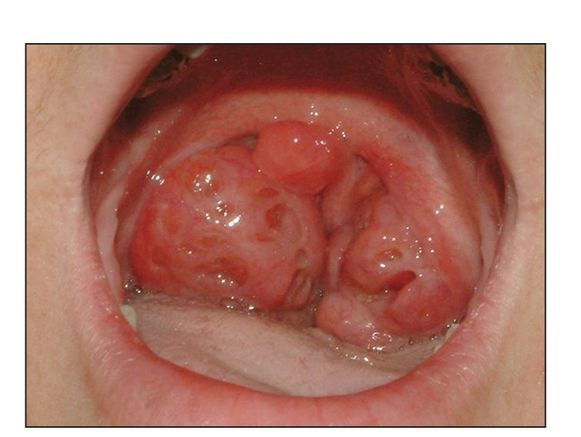

Fig 9-10 Enlarged tonsils causing mouth breathing.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses